Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

All the Latest Improvements:

Vancouver Photographic Studios of the Nineteenth Century

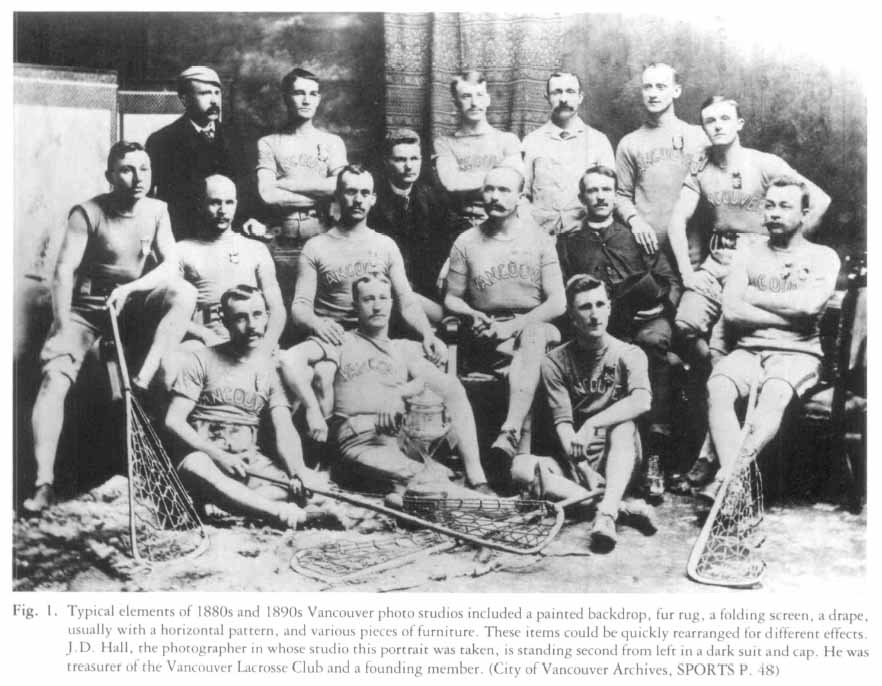

1 While portrait photographs reveal much about dress, social customs, and the degree of assimilation of immigrant groups, the circumstances under which such carefully staged images were constructed have not been sufficiently explored. The photographic studio of the nineteenth century was often an elaborate stage, yet few glimpses have been offered behind the scenes. Three detailed newspaper descriptions of Vancouver studio interiors provide a better understanding of this carefully fabricated milieu. Comparative and cooperative studies between photographic archivists and material history researchers are needed to broaden our knowledge of Canadian photographic portraiture.

2 The photographic studios of nineteenth-century Vancouver were located in a variety of structures, from tents to specifically commissioned photographic studios. Two photographic firms, Milross & Wren and J. A. Brock & Co., had opened studios in frame buildings within a week of each other and two weeks before the major fire of 13 June 1886 which almost completely destroyed the city.1 Milross & Wren operated as a portrait studio but no surviving work has been identified. The other company, a partnership of J. A. Brock and H.T. Devine, both formerly of Brandon, Manitoba, specialized in outdoor photographs but did take interior portraits. No studio portraits by Brock & Co. before the fire have been discovered. Following the fire, only J. A. Brock & Co. carried on business, at first in a tent on Cordova Street, and subsequently in the first brick building erected after the fire, the Home Block on the south side of Cordova Street between Seymour and Richards.

3 As happened with other studios in Vancouver, Victoria and elsewhere, the Brock & Co. studio was utilized by two further photographers. James Deakin Hall (1854-1936), senior partner in Hall & Lowe, formerly of Winnipeg and by 1885 established in Victoria, located in the same building in October 1887. He called his portrait studio the Vancouver Photo Company. His portrait setting is distinctive (fig. 1) and featured a patterned curtain, a Japanese folding screen, and a fur rug. When David Wadds bought out the Vancouver Photo Co. from Hall in May or June 1892, Wadds retained the studio decor for a period. This was probably not an uncommon practice as a new photographer probably did not have money to invest on fresh backdrops.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Robert W . Anderson, likely the first itinerant photographer to visit the new city, appears to have operated out of a room in the White Swan Hotel, but probably did outdoor work. His ad read "Views and groups taken to order."2 Other itinerant photographers, such as the stylishly titled Great Eastern Photographic and Advertising Company, established themselves in tents, but as time went on other itinerants gained in respectability by renting space in vacant rooms. The Rocky Mountain Portrait Co., for example, in Vancouver for one day, March 15, 1894, occupied a store on the ground floor of the Metropolitan Block at the corner of Hastings and Homer streets.3

5 Railway cars were also outfitted as photographic darkrooms. William McFarlane Notman (1857-1913) was provided with such a car on his trips west in the 1880s. Alexander Henderson (1831-1913), a Montreal contemporary of Notman's, was officially employed as a CPR photographer beginning in 1892. He made a trip west in the same car used by Notman. A Vancouver newspaper described it as "The C.P.R.'s Shadow Catcher. The funny car with the three dark windows that has been in Vancouver for the past ten days...is the travelling home and workshop of Mr. Henderson, photographer for the C.P.R., who has been taking a number of views in Vancouver and vicinity "4 Another paper commented that "Mr. Henderson is travelling in a car that has been specially fitted up for him, and many people who saw it on the side track wondered what it was, as some of the windows are darkened in order that he may develop the photographs."5 These travelling darkrooms were used to provide nearly instantaneous results so a photographer could check the quality of his work and rephotograph if necessary.

6 As with other municipalities, the Vancouver City Council regulated construction activity through a council committee known as the Board of Works and through the city fire inspector. A recent arrival in the city, John E. Thompson, complained to council in November 1888 that the fire inspector "has ordered me to remove some boards constituting part of the roof of my photographic canvas tent at the back of the premises No. 76 Cordova Street—I have lately arrived from the East and the boards are intended to afford only a Temporary shelter during the winter, when the risks of fire as regards roofs are at a minimum." The boards, he stated, were necessary as they were "laid over a tent roof for water shelter."6

7 In June 1898, I.B. Snell wrote to City Council requesting permission to operate a portable studio (he probably meant a tent) until such time as he could open a permanent studio in a building. He complained to Vancouver City Council that there were simply not enough buildings of a suitable nature.7 His request appears not to have been granted, for he next surfaces as a photographer in Rossland.

8 Both the fire inspector and the Board of Works were involved in approving plans for the erection of a roof-top photographic studio by the Stanley Brothers in 1889. The brothers sought permission in July and must have received it by September when a newspaper stated "Messrs. Stanley Bros, will commence today the erection of a photographic studio in the Chamberlain building, corner of Carrall and Powell streets."8 The studio was opened in mid-October 1889.9 A November 1889 fire insurance map refers to the Stanley Bros, studio as a tin-clad photo gallery on roof; "lodgings and photo" were shown on the second floor.

9 John White's "photo tent" is also shown on the same map, while John Thompson's studio and apartment appear on the second floor of a building at the corner of Cordova and Carrall streets. James Deakin Hall (1854-1936), who established a photo studio in October 1887, also appears on the map as "Photos & Dwelling" at 416 Cordova Street. Bailey & Neelands, who did not, so far as is known, operate as a portrait studio, are shown on the map in a first floor location at 127 Hastings Street as "Books & Photos & Picture Frames."

Display large image of Figure 2

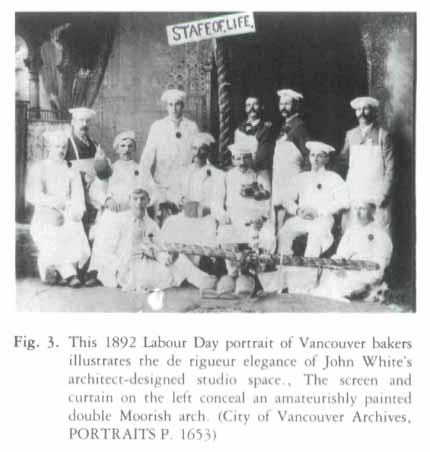

Display large image of Figure 210 The first Vancouver photographer to commission a portrait studio design was John M. White. He called upon the talents of Vancouver architect R. McKay Fripp in 1891 who "specially arranged for Mr. White the photographer" six rooms on the second story (called the first floor) of a new building which would include "a darkroom, studio, reception room, waiting room, etc The entrance [to the second story on Oppenheimer Street, now E. Cordova] will be surrounded by a balcony, and will be heavily arched with rock-faced stone. One of the chief features of the building will be a handsome circular bow window on the corner."10

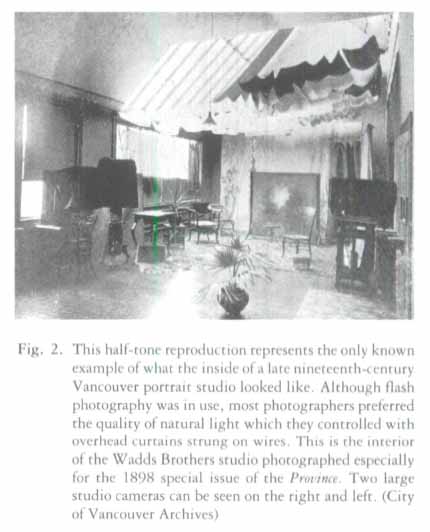

11 The building, jointly owned by the real estate firm of Graveley and Spinks, was known for a while as the Graveley-Spinks Block. It stood on the southeast corner of Oppenheimer and Carrall streets. After White moved to 14 W. Cordova about 1897, his studio was used by the photographer H.D. McKay between about 1897 and 1899, and then by Alphonse E. Savard (1864-1934) from about 1899 to 1915. The building no longer exists. A half-tone illustration of the Graveley-Spinks block under H.D. McKay's tenancy appears in a souvenir edition of the Province newspaper published in the spring of 1898 (fig. 2). Also in this issue were half-tones of the exteriors of S.J. Thompson's Vancouver and New Westminster studios and the interior of the Wadds Bros, studio.

12 Upon White's move into his custom-built quarters, a complete description of the interior was published in November 1891. A portrait taken in 1892 (fig. 3) conveys something of the contrived elegance of White's studio and confirms this first detailed portrayal of the interior of a photo studio in Vancouver:

13 Competition within the Vancouver photographic community was fairly stiff. Most photographers did nor advertise and therefore relied on word-of-mouth or physical presence in a central business location for customers. One newspaper, the News-Advertiser, often provided free advertising in the form of long notices such as that given White. Thomas Bell Straiton (1869-1955), a contemporary of White's, had his studio described in 1893 in much the same detail. No interior portraits by Straiton from this studio have been located:

14 One of the last Vancouver portrait studios to open in the nineteenth century was designed for Stephen Joseph Thompson (1864-1929), a prolific and brilliant photographer originally based in New Westminster. Within three months of relocating to Vancouver from New Wesrminster, or by early March 1898, he had opened an opulent photographic centre as seen by the eyes of yet another News-Advertiser reporter:

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 315 Vancouver photographers were as progressive but not necessarily as innovative as their counterparts in other North American cities and towns. They sought to maintain competitive advantages through continual modernization of their equipment and redecorating of their interiors. The city's notorious wet weather was even exploited by some photographers through newspaper advertisements such as this one — "Never Mind the Weather. Brock & Co. can take photos in all kinds of weather."14 Other photographers were more cautious — "Before the Rainy Season Sets Regularly in Have Your Photo Taken at the New Vancouver Photo Co'y."15 Flash photography was not extensively practised inside the studio, but was used in a variety of other interiors beginning in the mid-1890s.