Articles

Economic Choices and Popular Toys in the Nineteenth Century

Les fabriques de jouets d'Angleterre, d'Allemagne et des États-Unis approvisionnaient une bonne part du marché canadien à la fin du XIXe siècle. En 1871, la valeur des importations de jouets s'élevait à 27 000$, soit un volume d'environ 300 000 objets pour trois millions et demi de Canadiens. On trouvait de tout, à tous les prix, la gamme allant des animaux en bois ou en matériel synthétique et des jouets américains en fonte pour un sou, au cheval à bascule le plus coûteux à 15$. La plupart des jouets étaient vendus aux membres de la classe moyenne grandissante du Canada, mais de petits jouets simples étaient vraisemblablement assez bon marché pour être achetés, en milieu urbain, par les salariés des usines et, en milieu rural, par les petits propriétaires terriens qui pratiquaient une économie d'échanges et qui possédaient un peu d'argent liquide. Les jouets les plus populaires étaient fabriqués à la maison ou achetés en magasin; ils reflétaient le monde des adultes vu par un enfant. Ils constituaient probablement les premiers jouets offerts à l'enfant. Il s'agissait de chevaux à bascule en bois, chevaux sur roulettes, poupées, traîneaux, meubles d'enfant et poupées en chiffons.

Résumé

The commercial toy industries of England, Germany and the United States supplied much of the Canadian market in the late nineteenth century. By 1871 the value of imported toys had grown to $27,000, representing a volume of about 300,000 items for 3.5 million Canadians. In variety and price toys ranged from simple wooden and composition animals and American cast iron toys for a penny to the most expensive rocking horse for fifteen dollars. Most toys were marketed to a growing Canadian middle class, but the small, simple toys were likely cheap enough to be bought by city factory wage earners and small farm owners who worked in a self-sufficient barter economy with little surplus cash. Popular toys, available in homemade and commercial versions, reflected a child's view of the adult world and were likely the first toys owned by a child; these are identified as wooden rocking horses, horses on wheels, dolls, sledges, children's furniture, and rag dolls made from scraps of material.

1 First-generation research in the material history of a country usually involves an attempt to focus on what was being made in that country. The preliminary survey that I made on toys some ten years ago was this type of analysis, based on a reading of the Montréal Gazette from September to December at ten-year-intervals to see what was being advertised in Montréal, Canada's major importing centre; on a check of Canadian directories from 1851 to 1900, and of some Montréal and Toronto directories to see what Canadian-made toys were being advertised; and on a look at several public and private collections of toys. Such a general survey allows one to extract a skeleton framework for understanding what toys might have been available, and what kinds of toys were being made by Canadian toy makers.1

2 With the broader conference topic of "Children and Changing Perspectives of Childhood in the Nineteenth Century" in mind, it seemed more useful to look at several other aspects of toys in Canada, such as the value and volume of imported toys being sold commercially in Canada; the relation of toy prices to wage figures for salaried workers to determine what types of toys a family could afford for its children; and the identification of "universal" toys, that is, those made by individual toy makers, by factory workshops and by adults and children in the home, and those first owned by a child from a much wider possible selection.

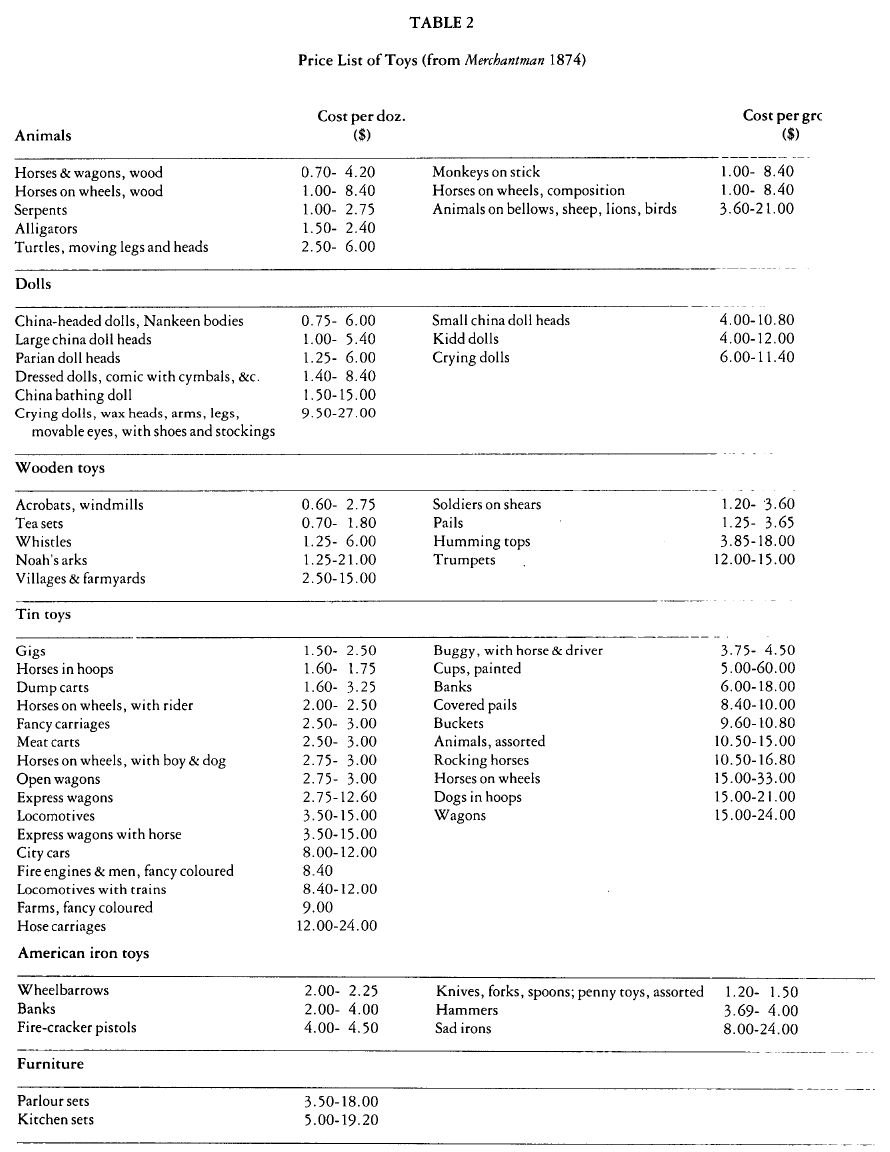

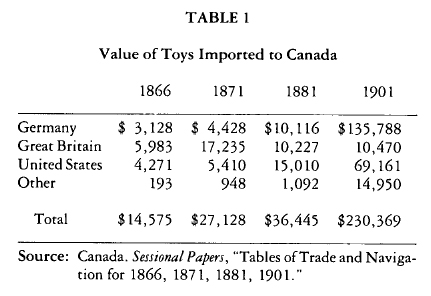

3 In England and continental Europe the early years of the Industrial Revolution created a new and affluent middle class whose view of children and education was changing. No longer were children seen simply as small adults. They were treated as a special group who needed recreation and play, along with affection and a firm religious and moral training. A growing market, the new attitude toward children, and the acceleration of industrial inventiveness in mass production methods spurred the growth of a commercial toy industry. Toy manufacturers in England, Germany, France and the United States, particularly after 1850, supplied not only their own market but also exported toys to Canada, as is shown in Table I.

Display large image of Table 1

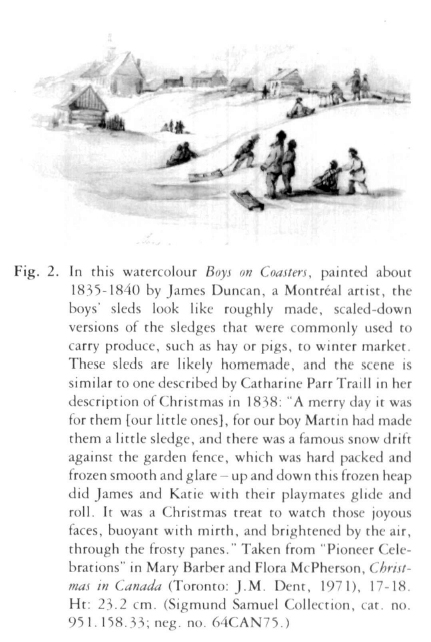

Display large image of Table 14 Those figures, although they convey the value of toy imports, do not indicate either the variety or extent of toys being brought into Canada. In 1874, the Merchantman, a Toronto wholesale trade review, published a review and price list of toys.2 The following rearrangement (Table 2) of that extensive list shows more clearly the wholesale price ranges. The most expensive toys were:

Large show window dolls $2.00-$4.50 each

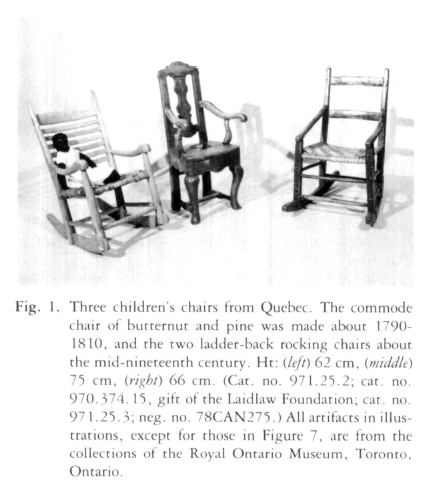

Rocking horses, wooden $2.25-$15.00 each

Other toys were sold by the dozen or by the gross (twelve dozen, or 144 items).

5 In the wholesale prices quoted:

0.60- 1.20 per doz. or

7.20-14.40 per gross = 0.05-0.10 each

1.20- 2.40 per doz. or

14.40-28.80 per gross = 0.10-0.20 each

2.40- 4.80 per doz. = 0.20-0.40 each

4.80- 9.60 per doz. = 0.40-0.80 each

9.60-19.20 per doz. 0.80-1.60 each

In all cases retail prices would be about 40 per cent higher.

6 In the same 1874 article, retailers were advised to order cases of assorted toys: $12.83 for a case of a 250-item assortment, which would give an average wholesale price per item of 5 cents; $18.25 for a 200-piece assortment, an average of 9 cents per item; $29.00 for the 120-piece assortment, an average of 26 cents per item; and, $40.50 per case of 100 pieces of higher quality, or 41 cents per item. For the 1871 value of $27,000 worth of toys being imported into Canada if we assume the $18.25, 200-piece assortment price as an average one, that import figure represents about 300,000 toys for a population of a little over 3.5 million people.3

7 All the different types of toys were made in a variety of sizes, with care and in a wide range of prices to suit different pocketbooks. For one cent one could buy a monkey on a stick, a composition horse on wheels, wooden soldiers on shears, wooden pails, and the American cast iron knife, fork, spoon and penny toys such as cast iron trivets and miniature guns. For five cents one could buy wooden animals on bellows, such as sheep, lions and birds, small china doll heads to make into dolls at home, kid dolls and crying dolls, wooden humming tops, tin buggy with horse and driver, tin banks, and painted tin cups. The most expensive toys were the speaking dolls that said "mama" and "papa" selling for $1.60 to $2.40 each and the wooden rocking horses for $2.25 to $15.00 each.

8 Although a great variety of toys was available, the number and source of toys that any particular child might have would depend on the economic circumstances of the family. For adult workers in manufacturing industries in Nova Scotia in 1878, wages varied from about $5.00 to $11.00 a week. Although there may be some regional variations, wages were similar for workers in other provinces. An unskilled labourer might earn $1.00 a day. Skilled workers, such as furniture makers, foundrymen, forge workers, upholsterers, clothiers, carriage makers, boot and shoe makers, contractors, builders and woodworkers might earn $7.50 to $8.00 a week. Stove makers and machinists could earn $10.80 a week.4 For these wage-earning parents it is doubtful that they could spend a day's or even a half day's wages for a toy. Money for toys, if any were available after buying necessities, would probably be for the simple penny or 5 cents variety. In many of these families the children themselves might also be wage-earners. Up to 1880 in some city factories children as young as ten worked ten-hour days to supplement their family's income. There would be little time or energy left for play. Toys for these children might also be homemade or improvised by the children themselves.

9 On some small farms or in areas of Ontario where land was still being opened for settlement in the 1870s and 1880s, the family might be self-sufficient in supplying its own food, but might not be producing enough of a surplus to generate a cash income. Children on most farms would be expected to help with chores. In this situation again there would be little carefree time for play and toys would likely be homemade.

10 The middle and higher priced toys in the 1874 list would have found their way to the homes of a growing Canadian middle class of wholesale and retail merchants, importers and shippers, factory owners and prosperous farmers, and into the homes of the professional engineers, doctors, lawyers and government officials.

11 The kinds of toys found in both homemade and manufactured versions would be in use by children across the economic spectrum. Such toys, including special furniture for children, made in simple versions by hand, were also the staple products of early Canadian toy manufacturers. In their efforts to compete with an already established toy trade from Germany, Great Britain, and the United States, Canadian companies made those items that were most saleable; these same toys remained bestsellers well into the twentieth century. The most widely produced and most enduring in popularity were toys mimicking the visible physical activities of the adult world: taking produce to market with a horse and cart; riding a horse to visit neighbours; clothing, feeding, and bathing young children; and preparing and serving meals. They reflected what children saw of adult work and it was natural for children to learn by imitating that work, with or without the assistance of toys. The most common toys seem to have been wooden ones, such as hobby horses, rocking horses, horses on wheels, horse or ox and cart, wooden dolls and furniture, sledges and sleighs, and children's chairs. Of a much wider selection, these would be the first toys a child might be expected to have, whether roughly executed and homemade or the most finished and expensive that money could buy.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

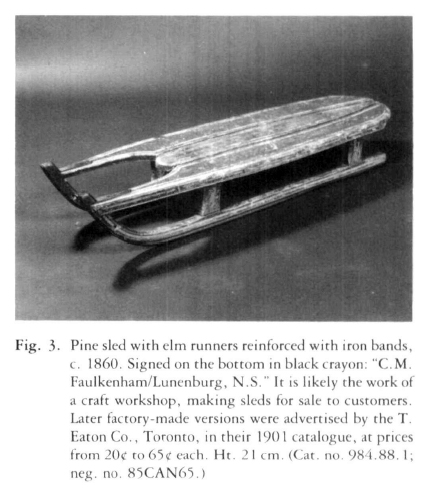

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

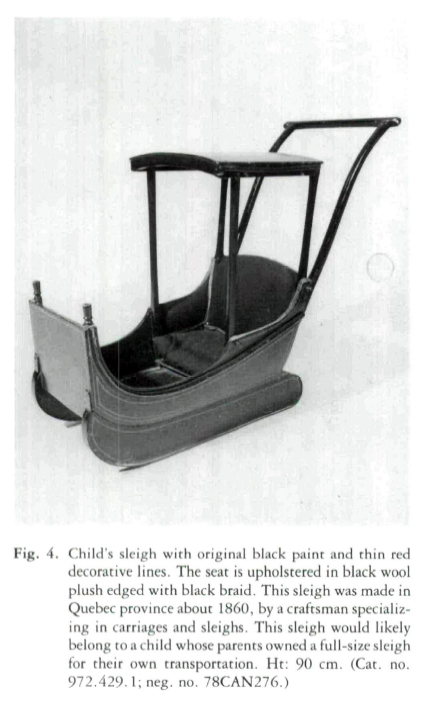

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

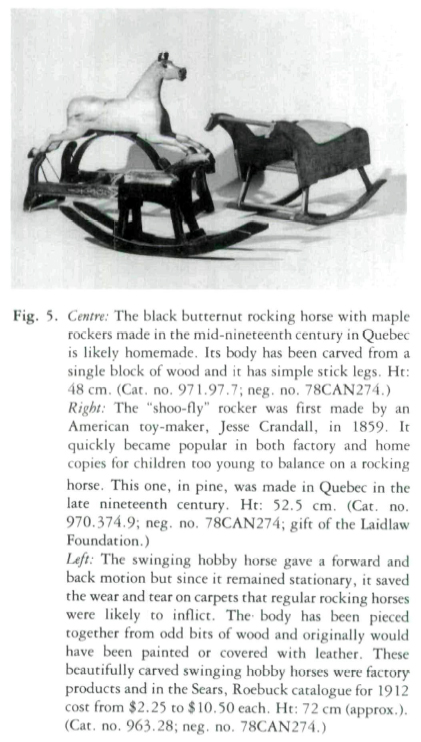

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

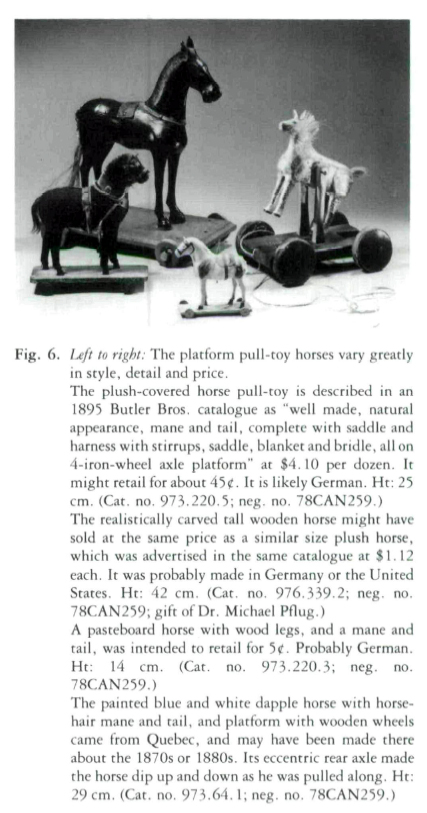

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

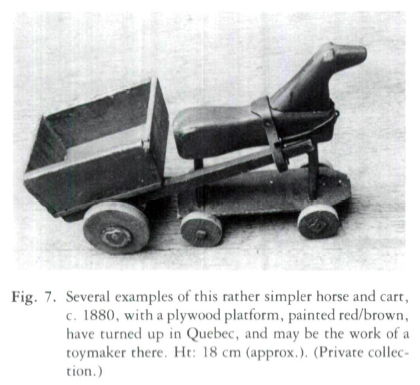

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

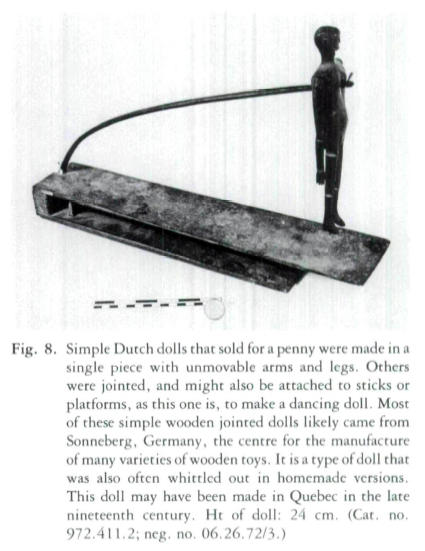

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

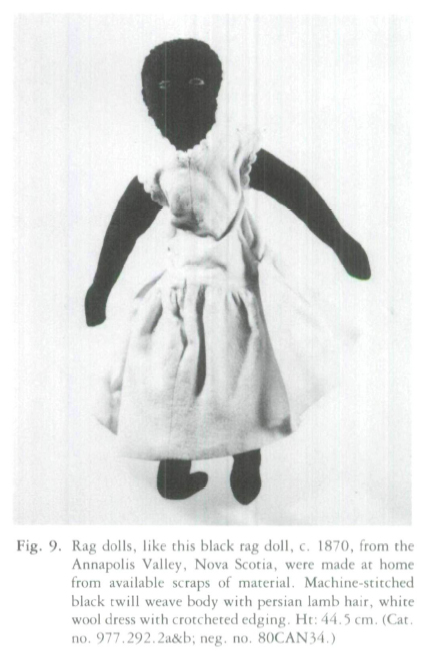

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

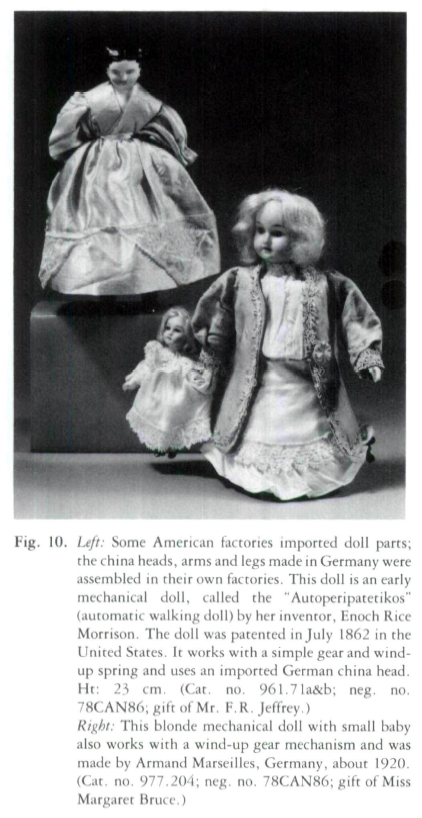

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10