Articles

Diffusion and Vision:

A Case Study of the Ebenezer Doan House in Sharon, Ontario

Résumé

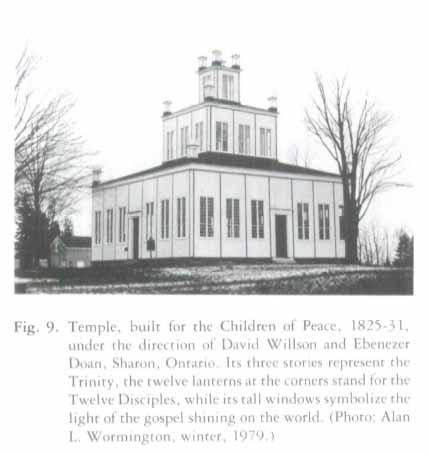

Cette recherche effectuée sur la maison Ebenezer Doan, qui fut érigée en 1819 à Sharon (Ontario), montre comment une construction qui semble ordinaire peut livrer des renseignements à propos des courants qui en ont influencé l'architecture et des informations sur le caractère et la formation de l'entrepreneur. On y reconnaît l'influence britannique et germanique particulière aux maisons de la Pennsylvanie. Les loyalistes avaient introduit et modifié ce style dans le territoire qui deviendra le Haut-Canada. La grande cuisine de type traditionnel de la maison Doan, centre de la vie familiale, indique à quel point la famille désirait préserver des relations étroites avec les parents et amis restés en Pennsylvanie, malgré l'obstacle de la distance créé par l'émigration. Les constructeurs comme Ebenezer faisaient preuve de conformisme, mais ceci ne les empêchait pas d'avoir une imagination créatrice et la volonté de l'exprimer. A preuve, nous pouvons nous référer au Temple et à la salle de travail que Doan construisit pour une secte religieuse appelée «Les enfants de la Paix».

Résumé

This case study of the 1819 Ebenezer Doan house in Sharon, Ontario, illustrates ways in which a seemingly simple, straightforward building may be analyzed to yield information about its architectural antecedents and its builder's background and attitudes. It suggests how British and Germanic traditions were interwoven on the Pennsylvania frontier, modified, and brought to Upper Canada by American settlers. In the Doan house, the very traditional hall/kitchen, which was the focal point of family life, reflects the Doan family's concern for maintaining close ties with family and friends from Pennsylvania despite the disruption of migration to a distant land. The conservatism of vernacular builders like Ebenezer Doan, however, did not preclude vision or the will to innovate. The temple and study Doan built for a religious sect known as the Children of Peace attest to that.

Introduction: The Concept of Diffusion in Studies of Vernacular Architecture

1 The concept of diffusion often has been used in studies of American vernacular architecture to account for the spread of house types and plans, methods of construction, and forms of decoration from one place to another. In his ground-breaking 1965 article, "Folk Housing: Key to Diffusion,"1 Fred Kniffen identified three major cultural areas - New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and the upper south — from which settlers moved across the continent, taking regional customs and traditions of building with them. Kniffen's ideas were expanded and refined a few years later in Henry Glassie's influential book, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States.2 These and other early studies of diffusion usually focussed on either plan or construction. For example, they documented the spread of the Continental three-room plan through Pennsylvania-German migration to the Valley of Virginia, into North Carolina, or westward to Missouri. Or, if concerned with technology, they cast light on the spread of log construction by tracing the paths of Pennsylvania-German and Scots-Irish settlers across the frontier. While adding to our knowledge of migration patterns and the geographic distribution of house plans and building methods, some of these early studies took an almost mechanistic approach to the question of diffusion, using field data to plot arrows on maps as if movement itself were all that mattered. More recent studies, however, have been more sophisticated in their approach, using the concept of diffusion to illuminate broader issues of cultural interaction and the way one culture may be influenced by another. For example, Henry Glassie's 1972 study, "Eighteenth-Century Cultural Process in Delaware Valley Folk Building,"3 presented a sophisticated analysis of ways in which Georgian balance and symmetry were used in conjunction with traditional Continental-plan houses of the Pennsylvania Germans. He suggested accommodation rather than assimilation. Another important study is Edward A. Chappell's "Acculturation in the Shenandoah Valley: Rhenish Houses of the Massanutten Settlement."4 There Chappell drew on architectural evidence to illuminate the gradual and complex acculturation of German-speaking settlers by their Anglo-American neighbours. These and other recent analyses of American vernacular architecture have benefitted from the work of structural anthropologists such as Claude Lévi-Strauss in their abandonment of mechanistic approaches to diffusion and overly simplistic analyses of the migration and influence of styles or forms from place to place. Following the lead of the structuralists, they have seen vernacular architecture as the tangible expression of complex underlying systems of thought and belief. Semiotics, or the study of relationships between signs and symbols and what they represent, also has been influential in diffusionist studies wherein architectural forms themselves have been seen as signs and symbols indicative of cultural values. Still another approach incorporates the concept of proxemics, the study of man's use and perception of space as an aspect of his culture.

2 Investigations of Canadian material history also have shown increasing interest in the concept of diffusion. While not primarily concerned with architecture, John J. Mannion's Irish Settlements in Eastern Canada: A Study of Cultural Transfer and Adaptation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974) is a thought-provoking analysis which searches out the roots of Irish-Canadian traditions and studies how they were modified, weakened, and sometimes strengthened, as they spread to the New World. Mannion compares three areas of Irish settlement — the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, northeastern New Brunswick, and Peterborough County, Ontario. In doing so, he cautions against assumptions that the ways of the Old World all began to decline once they came to North America and that the process of cultural change and diffusion was in any way uniform or automatic in all parts of the country. Gerald L. Pocius's recent studies of Newfoundland vernacular architecture5 and John Lehr's work on Ukrainian vernacular buildings in Alberta6 also use a sophisticated approach to the concept of diffusion and the way traditional forms changed to meet local needs.

3 As studies in diffusion grow in number and complexity, however, we should not lose sight of the potential for innovation and originality among vernacular builders. It is tempting sometimes to look for precedents for everything or, in reaction to long-standing myths of the sturdy independence and resourcefulness of yesterday's craftsmen, to argue only for conservatism and dependence on custom and tradition.

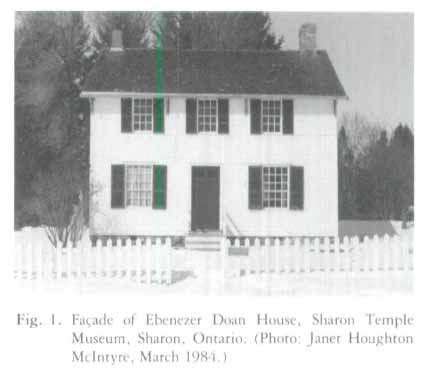

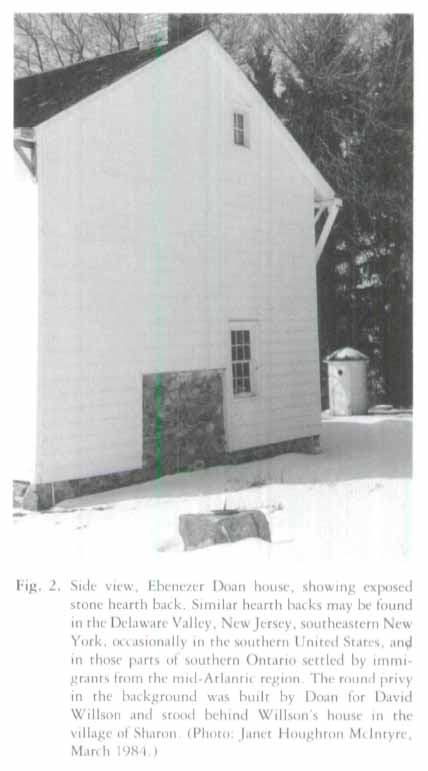

4 This paper may be read as a case study, using the Ebenezer Doan house (figs. 1 and 2) to show how a seemingly simple, straightforward building can be researched and can provide evidence of complex and subtle historical processes, of cultural diffusion and the intimate relationship between people and their material possessions. It will also suggest the potential for vision and originality, as well as adherence to precedent, in the work of the vernacular builder. The Ebenezer Doan house, built in 1819 in East Willimbury Township, York County, Upper Canada, illustrates the movement of ideas across national boundaries, from rural Pennsylvania to a new British colony some 700 km away. It shows how an architectural form found in the mid-Atlantic region was brought to Upper Canada and modified. The result was a very conservative dwelling closely recalling the houses Doan had seen in Bucks County but differing from them in significant ways. Its conservatism was an expression of the Doan family's high regard for family and community life, both of which they were able to sustain almost intact despite the disruption of migration and change.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2Historical Background: The Doan Family and Their Move to Upper Canada

5 Ebenezer Doan (1772-1866) was both a carpenter and a farmer.7 His great-grandfather, Daniel Doan (or Doane), had to move to Newtown, Bucks County, from Cape Cod in 1695. He too had been a carpenter and farmer, like many other members of the Doan family before and after him.8 By 1808, new land was becoming scarce in the states along the eastern seaboard and Ebenezer Doan must have wondered how his sons could ever afford to buy farms of their own. Some fifteen years earlier, he had tried his luck in Georgia, but returned to Pennsylvania after only a short Stay.9 Now increasing numbers of the Society of Friends, to which Doan belonged, were moving north to Upper Canada. National boundaries must have meant little to folk whose religious beliefs forbade them to swear oaths of loyalty to any earthly power; besides, land in Upper Canada was cheap and abundant. As the Friends had already started meetings there, Doan's move is not hard to understand.10

6 The uprooting effects of migration were lessened by the fact that Doan and his family left Pennsylvania in the company of many of their Bucks County relatives and neighbours. With them were Ebenezer's hither, his three brothers and a sister.11 One third of the friends and relatives who had attended his wedding in Bucks County in 1801 became his neighbours in Upper Canada.12 Ties with family and friends may have been particularly strong among Quakers migrating from Pennsylvania to a new land where they would be much more obviously a religious minority. These ties were carefully maintained well into the second generation, while the journey between Upper Canada and Pennsylvania was taken almost casually. In 1830, one of Ebenezer's sons wrote to his cousin back in Bucks County, "It is just as easy for thee to come to Canada as it is to go to Philadelphia, only it takes a little longer."13 Closely tied to the North American tradition of liberal individualism was a conservative bent which in Upper Canada, as in Pennsylvania, found expression in old ways, family ties, and familiar forms of social organization.

7 On arriving in Upper Canada, Doan purchased a partially cleared farm near the Yonge Street Friends Meeting House, about 40 km north of York (Toronto). In 1818, the Doans moved to Hast Gwillimbury Township, about 10 km to the east, purchasing a farm of 200 acres, lots thirteen and fourteen in the third concession. There Doan built a new frame-house the following year.14

8 The Ebenezer Doan house stands today on the grounds of Sharon Temple Museum, about 2 km south of its original location. While it has been moved from its early setting of farm fields and outbuildings, much of its original context may be re-established through documentary and material sources. More important to its validity as a historical document, however, is the fact that it has remained virtually unaltered both inside and out. Plumbing and electricity never were installed. For many years before its acquisition by the York Pioneer and Historical Society, it was used as a farm storage building on its original site.

Architectural Antecedents in Bucks County, Pennsylvania

9 Many small houses contemporary with the Doan house and exhibiting similar front and rear elevations may be found in Bucks County and elsewhere in the mid-Atlantic region. Examples include the Abdon Hibbs house (fig. 3), not far from the farm where Doan's father once lived,15 and several small houses in Solebury Township, close to where Ebenezer himself had a farm. All were built after the Doans had left the area and attest to the continuing popularity of this common three-bay form. Its symmetrical façade may have had as much to do with vernacular tradition as with any "trickling down" of the Georgian style from elaborate dwellings. Small houses with symmetrical three-bay façades appeared in the British Isles in the seventeenth century and may have inspired some of the early houses built in Bucks County by English and Scots-Irish immigrants.16 Furthermore, as Henry Glassie has pointed out, "Bilateral symmetry was intact, an essential feature of western European folk design."17

10 Several features, however, set the Doan house apart from most of its surviving Bucks County contemporaries. Its first-storey windows are wider and more in keeping with earlier fashion than with those in surviving Bucks County examples of similar date. More striking differences, however, may be found in materials and dimensions.

Display large image of Figure 3

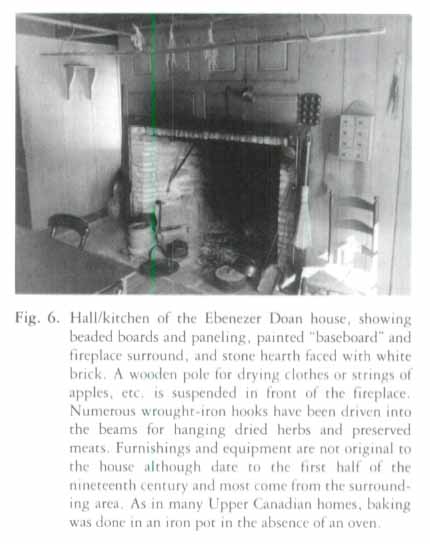

Display large image of Figure 311 The Ebenezer Doan house is of frame construction. Most Bucks County houses, however, are built of stone. In Doan's time, frame-houses may have been more common in Bucks County than they are today, but not much more. While surviving tax and assessment records for Solebury Township do not provide any detailed information regarding house construction and size, those for Plumstead, immediately to the north, do. Out of 187 buildings listed in preparation for the Direct Tax of 1798, only one was of frame construction. Sixty-five were log, while the remainder were stone.18 To the south, in Upper Makefield Township, a similar pattern may be seen through a tax list compiled in 1795 or 1796. There, one of the few frame-houses listed in the township was owned by Ebenezer's great-uncle, Benjamin Doan.19

12 In building a house in Solebury, Doan would have worked in company with stonemasons. The masons would have built the walls, chimneys and fireplaces, while Doan would have been responsible for interior partitions and trim, the windows, doors, and roof. As a carpenter, he probably also would have drawn the plans, supervised the masons' work, and subcontracted any additional work in joinery, glazing, plastering, and painting. The dominant role of the carpenter is shown in Joseph Moxon's widely read Mechanick Exercises or the Doctrine of Handy-Works, Applyed to the Art of House-Carpentry. It persisted even in those parts of Britain and America where houses built entirely of wood were rare.20

13 While Ebenezer's work in the United States cannot yet be documented, that of his older brother, Jonathan, can. Like Ebenezer, Jonathan is listed in Bucks County deeds as a carpenter.21 Yet in 1791, he was hired by the state of New Jersey to erect a state house in Trenton to be built of stone. In the state records of the time, Jonathan Doan is noted as a "master carpenter," an "undertaker," or an "agent," and was responsible for designing the building, planning, buying supplies, and supervising and paying the workmen.22 He performed similar duties in building the state prison and, several years later, in erecting stone buildings for the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University.23 Jonathan, who was seventeen years older, gave Ebenezer his early training.24

14 In addition to assisting in and supervising the building of stone houses, Ebenezer Doan may also have built log houses in Solebury which, judging from the tax assessment records from Plumstead and Upper Makefield, must have been numerous. A good log house required considerable skill in construction and was not the work of an amateur. Doan's working life as a carpenter in East Gwillimbury must have been very different from what it had been in Solebury. In East Gwillimbury, frame-houses were much more common, although there, as in Solebury, log houses were abundant as well. In both areas, the skills of a carpenter were essential to the community.

15 The dimensions of the Doan house, 25½ feet long by 21½ feet deep,25 also set it apart from most Bucks County examples. English settlers in the county tended to build more nearly rectangular houses, one room deep, with end chimneys and fireplaces. The ground floor of these houses generally contained one or two rooms, a hall and a parlour, one opening into the other.26 The lack of detailed records for Solebury makes analysis difficult, but surviving houses from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries suggest that this general shape and plan were common. By the latter third of the century, however, increasing numbers of two-room-deep, two-storey houses were being built in the Georgian mode.27 Evidence from the 1798 Direct Tax for neighbouring Plumstead, where forty-six two-storey houses were listed, yields average overall dimensions of approximately 29 by 21 feet, further supporting the theory that rectangular houses were the norm.

16 The Doan house, however, is more nearly square and resembles houses built by Pennsylvania Germans,28 rather than those built by settlers of English background. Its first-floor plan (fig. 4) is reminiscent of the Continental three-room plan which includes a large hall/kitchen and two rooms off to one side. In the Doan house, one of these two rooms is rectangular, while the smaller one-behind it is more nearly square, again in keeping with Continental tradition. The hall/kitchen of the Doan house has two anterooms that may be considered part of the hall/ kitchen space. The smaller of these has shelves on three sides and could have served for storing crockery, dishes and foodstuffs. In a sense, it was similar to a built-in cupboard. The larger one is more nearly a separate room, approximately 6 feet by 7 feet square and lighted by its own window. Here wider shelves are to be found at one end and a dry sink by the window. The presence of these two spaces, which are original to the house's construction, provides a variation on the traditional three-room plan but still allows the Doan house to be seen within the context of a three-room-plan house. Another variation occurs in the location of the boxed-in stairs which are placed near the middle of the back wall rather than in a corner location as favoured by most Continental-plan houses.

17 If the Doan house does indeed reflect Germanic influence, Bucks County antecedents may again be found, despite the overwhelmingly British background of most of its people. Germans, as well as English, numbered among Bucks County's eighteenth-century settlers - including Anna Savilla Sloy, Ebenezer's mother.29 In Hilltown, Bedminster, Tinicum, and Plumstead Townships lived a number of German Mennonites, including members of at least sixteen families who, between 1786 and 1802, made their way to Upper Canada.30

18 A major difference between the Doan house and the "typical" Continental-plan house lies in the fact that it uses end chimneys rather than a central chimney. Even this, however, does not remove it entirely from Pennsylvania-German precedent. The Daniel Stong log house, built northwest of York (now Toronto) for a Pennsylvania-German family in 1816, used an end chimney with a three-room plan, while the Stongs' three-room-plan frame-house of 1832 used a centre chimney.31 The example of the Stong house upsets any attempt at a neat chronology of assimilation. The Stongs' second house in Upper Canada was more "typically Pennsylvania German" than their first. Probably many variations were made in the traditional Continental plan, even by settlers of known Pennsylvania-German ancestry.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 419 The Doans, however, were not of German background. They were Quakers whose ancestors probably had come from Wales.32 This suggests two other possible origins for the Doan house plan, including the so-called "Quaker-plan" house said to have been inspired by a promotional pamphlet printed in 1681 and once attributed to William Penn. In that pamphlet are instructions for building a house with one large room and two smaller rooms oil to one side. It has been suggested that this plan derived from early Swedish precedent in the lower Delaware Valley and was spread by Quaker missionaries throughout the colonies.33 These claims are hard to substantiate, however, in light of the fact that most documented examples of Quaker-plan houses cannot be traced to early Quaker builders or Quaker owners. Also, Quaker-plan houses are rare in areas of highly concentrated Quaker settlement, such as Bucks County. A more compelling argument could be made that the three-room plan comes from British precedent, particularly from the north and west of England and from Wales, where the majority of Pennsylvania's Quaker settlers originated.34 While less common than hall or hall-parlour houses in these areas, three-room plans and their variants may be found.35

20 The Doan house plan may be seen as an amalgam of British, German and American precedent deemed suitable to the needs of a large family of two parents and seven children.

21 While the location of the Doan farmlands in Solebury Township is known, Ebenezer Doans house and the houses of his father and brothers no longer survive, so that a direct comparison cannot be made with the house in last Gwillimbury. However, surrounded on three sides by land once owned by the Doans, stands an eighteenth-century stone house (fig.5) which is similar to the Doan house in Upper Canada in several important ways Measuring approximately 32 by 34 feet, the house contains three rooms on its main floor. One enters the Solebury house from the front through a door set in the middle of a three-bay façade. This door leads directly into the hall/kitchen with its large cooking fireplace set against the gable wall. To the right are two smaller rooms of roughly equal proportions. A boxed-in stairway ascends to the second floor from a point adjacent to the back door, which, as in the Doan house in Upper Canada, is located directly opposite the front door. Ebenezer Doan must have been familiar with this house since his farm was located immediately next to it.36 With its similar shape and floor plan, this house provides a tangible link with Solebury Township precedent.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 522 Despite its similarities, the Solebury house differs from Doans house in East Gwillimbury m several respects. Most obviously, of course, it is built of Stone. But there are subtler differences as well. The small back room on the third floor appears to have been accessible only through the small front room and not through the hall/kitchen. This follows Continental, rather than British, precedent for three-room-plan houses. Also, the roof frame is quite different from preferred Anglo-American types.37

23 Beaded pine boards are used for partition walls and sheathing throughout the hall/kitchen (fig. 6), its anterooms, the rear entryway, and the stairwell. Beams running from the front to the back of the house are exposed throughout the hall/kitchen area and are beaded at their lower corners. The ceiling boards they support are also beaded. This beading represents a reductive aesthetic dating well back into the eighteenth century and used in numerous vernacular houses. Beaded beams and ceiling boards are, however, rarer than beaded wall boards. The care given to finishing them in this way suggests the importance Doan must have attached to this part of his house. Unusual too are the pair of raised panels above the fireplace and the four panels — two of which form hinged cupboard doors — above them. The fireplace never had a mantel; instead, a band of dark stain was applied around the fireplace opening. A similar band simulates a baseboard around the rest of the room. While the walls were never painted, the four-panelled interior doors were coloured a dark reddish brown, suggesting a finer and more expensive wood than the pine used throughout the house. The ceiling too appears to have been painted or stained a dark colour originally, although now it is covered with darkened varnish, probably from the late nineteenth century.

24 The size of this room, its large open hearth for cooking, heat and light, and the exposed beams of the ceiling recall the interiors of much earlier houses. Like them, this room probably served as a traditional "hall," a place where many of the family's daily activities of indoor work and recreation would take place. We have already seen how highly Ebenezer Doan valued his family ties in moving with his father, brothers, sister, and other family members to Upper Canada. It was appropriate, then, that the hall/ kitchen, which stood at the heart of family life, should be the most traditionally arranged and decorated room in the house and the only room to have an exposed open-beam ceiling. The ceiling does much to give this room its highly traditional character but had a practical purpose as well: its exposed beams were useful for hanging things on hooks, while its dark colour would have hidden the stains of smoke and probably given a feeling of warmth more effectively than smooth white plaster ever could have done. In creating two anterooms for related work and storage, Doan may have been taking the first step toward separating the functions of kitchen and family living room. But it was a small step and one that did not disrupt traditional patterns.

25 Other rooms in the house, and also the façade, were more subject to changing modes of design and finish. In moving his family to Upper Canada, Doan showed that he was open to change. By moving with so many of his Solebury neighbours and relatives, he demonstrated too that he considered himself part of a larger group - a conformist, in a sense, who would not want his own house to be significantly different from the prevailing Georgian and neoclassical aesthetic of the time.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 626 It is far more complex than the roof structure of the Doan house in East Gwillimbury with its common rafters joined at the apex by pegged mortice-and-tenon joints, diminishing the possibility that Ebenezer Doan built the Solebury house as well.

27 The plan and construction of the Solebury Township house and the Ebenezer Doan house suggest a wide mixture of tradition and precedent, both English and Continental, which came together on the Pennsylvania frontier and then were taken far and wide wherever Pennsylvanians settled, only to be changed again to meet the needs of new situations.

28 The facade of the Doan house is more nearly in keeping with early nineteenth-century notions of Georgian design, while the hall/kitchen is more in the manner of vernacular building of a century before. Still there is little feeling of tension between outside and in. Style and efficiency accommodated each other. For example, one of tin downstairs windows is about a foot closer to the front door than is the other, in order to allow for the small storage room off the hall/kitchen.

29 The front door of the Doan house itself deserves comment. Two panes of glass are set into the upper portion of the door where one would expect to find wooden panels. These date to the time the door was constructed and like so many other features of the Doan house have a precedent in Solebury - in this case, the front doors of the Isaiah Paxson house built in 1785 at Center Bridge, not tar from the original Doan farm.38 The front door, like the back, was made in two layers with interior beaded boards, trapezoidal in shape, nailed to a joined frame. Inside, large hand-forged nailheads serve as decoration, conforming to the location of the stiles, rails, and muntins of the Georgian-style frame visible outside. The front door symbolizes the transition from the symmetrical, balanced façade to the more traditional hall/kitchen within. Outside appears a panelled Georgian door; inside, a door sheathed with boards of random widths studded with nailheads in the manner of the seventeenth century.

30 Opening off the hall/kitchen are two smaller rooms. The larger front room was heated by a small stove and probably served as a parlour; the smaller room behind it may have functioned as an unheated downstairs bedroom, close enough to the hall/kitchen to gain some benefit from the fire. Both these rooms have plaster ceilings and walls. Their doors and windows are trimmed with simple surrounds painted dark green. Beaded baseboards and chair rails, also painted dark green, provide the only other ornament in these rooms. Their smooth plaster walls and ceilings and their simply beaded woodwork follow neoclassical ideals of restraint and are much more in keeping with fashion than the traditional hall/kitchen beside them.

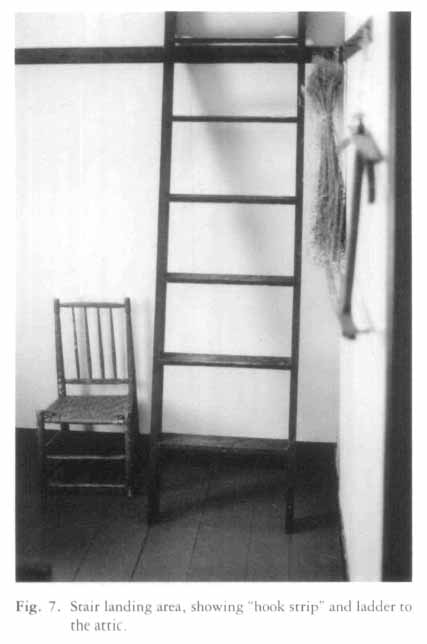

31 Upstairs, baseboards, chair rails, and door and window surrounds are virtually identical to those below and similar to those found in many other small houses throughout eastern North America in the early nineteenth century. Their simplicity has little or nothing to do with any Quaker aesthetic of plainness. Relating to southeastern Pennsylvania tradition is the "hook strip,"39 with nails for hanging things, found in the small room at the head of the stairs (fig. 7).

Display large image of Figure 7

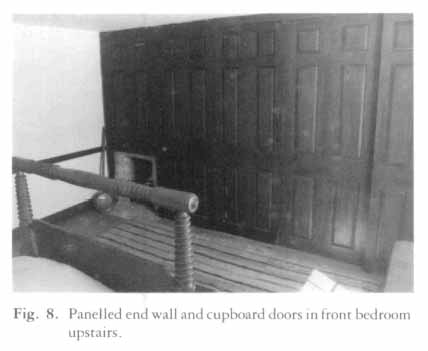

Display large image of Figure 732 More unusual are the small fireplace and fully panelled end wall in one of the two front bedrooms (fig. 8). This wall contains three hinged closet doors and is closely similar to a panelled end wall at the Isaiah Paxson house in Bucks County. The Paxson house carries a date stone inscribed "1785." Through tax records it is known that Ebenezer Doan was living nearby from 1783 to 1786,40 probably in the household of his brother or father, as Ebenezer himself did not become a landowner until 1801, the year of his marriage to Elizabeth Paxson, a distant cousin of Isaiah. Ebenezer must have known the Paxson house and could even have had a hand in building it.

33 The second floor of the Doan house is divided into four areas: the room at the head of the stairs, containing a ladder to the attic above and a "hook strip" which suggests that this room was used for work or storage; the heated bedroom with panelled end wall; a second bedroom at the front of the house, heated by a stovepipe from the parlour below; and a fourth room providing access to the second front bedroom.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 834 The Doan house was home to a family of nine: Ebenezer and Elizabeth Doan and their five sons and two daughters. It was the centre of a busy and productive farm — a scene distinctly different from the neat lawns and gardens surrounding it today. In 1830, 25 acres of wheat grew nearby. Other crops included corn, buckwheat and potatoes, and there was talk of growing peat trees from seed sent from Bucks County.41By 1834, the Doans had 45 acres under cultivation and kept three horses, four cows, and two homed cattle.42 In 1851, they had an orchard, grew 150 bushels of wheat, 110 bushels of oats, 80 bushels of peas, 60 bushels of turnips, and 40 bushels of potatoes. They kept three milch cows and a calf, three horses, twelve sheep, and six pigs. They processed 196 pounds of maple sugar, 75 gallons of cider, 60 pounds of butter, 30 pounds of wool, 12 barrels of pork, and 4 barrels of beef. They produced 14 yards of flannel and 9 yards of fulled cloth.43 The butter making, the picking, carding and spinning of wool, and the weaving likely took place in the rooms just described; the cider, the beef, and the pork probably were stored in barrels down in the cool cellar below the hall/kitchen. But other buildings were needed too, and the Doan house was only one of several buildings on the farm. Behind the house was a privy. Off to one side was a drive shed. In the other direction was a small frame-house built for Ebenezer's youngest son, David, probably about 1850, when he was given a small portion of his father's farm. By the end of the century, another generation had built a barn between the house and the road.44 Beyond these glimpses of the farm's operation and layout, little else is known. No wills with inventories listing personal possessions have been found.

Conclusion: Conservatism and Vision

35 At least in the early years at East Gwillimbury, Doan and his family must have known a life not much different from what they had experienced in Solebury. Their farm was about the same size, and the sort of subsistence agriculture they practised there was little different from what had been the norm in eighteenth-century Pennsylvania.45 Even in the act of seeing his son, David, settled in a house next to his own, Doan was repeating a familiar pattern, remembering, perhaps, the time when he had farmed in Solebury next door to his father and brothers. The house Doan built in 1819 was not unlike those of his former Solebury neighbours. Its plan must have reminded him of the stone house that stood next to his old farm in Bucks County. Perhaps his front door and panelled end wall brought back memories of Isaiah Paxson's house at Center Bridge. Close by were brothers and sisters and family friends he had known in Pennsylvania.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1036 By combining farming and carpentry, Doan also continued a tradition from the past. In 1794 Tench Coxe of Philadelphia had written,

37 Doan's house can be seen as a symbol of conservatism and accommodation in a new land. Its story is the complex tale of the spread and diffusion of ideas and ways of building from one place to another.

38 Still, an epilogue is needed. A few years after coming to Upper Canada, Ebenezer Doan left the Society of Friends and joined a new religious sect tailed the Children of Peace.47 In 1819, while building his own house, Doan erected a meeting house for this group which was quite unlike any meeting house in Bucks County. In 1S2"S, he began work on a three-storey temple (fig. 9), filled with religious symbolism and ornamented inside with columns, arches, and a staircase curved like a rainbow. In 1829, he built a whimsical study (fig. 10) for the founder of the Children of Peace, David Willson. It was David Willson's visionary leadership which is supposed to have inspired the designs for all these buildings. Sharing Willson's love of the unusual, Doan built him a round privy.48

39 The mind that planned the Doan house and the hands that built it, for all their conservatism, had within them the power to build other and different things, the will to innovate, and the capacity to experiment with new shapes, forms, and designs. Nothing in the Doan house itself prepares us for that. Yet perhaps it is a true guidepost after all. By 1850, a census taker found that Ebenezer Doan had returned to the faith of his fathers and once again was a Quaker.49

Research for this paper originally was undertaken for a graduate seminar led by Dr. Bernard L. Herman at the University of Delaware. Grateful thanks are expressed to Dr. Herman for his many insights into the study of vernacular architecture and also to the following people: Arlene Horvath of the Chester County Historical Society, Margaret Richie of Bucks County, and John I. Rempel of Toronto for their insights on house plans; Kathryn Auerbach and Jeff Miller of the Bucks County Conservancy for their assistance in locating the Doan farmlands in Solebury and access to their research files; Mr. and Mrs. Owen Colliflower of Solebury for their kindness in allowing me to photograph and visit their house; Daniel Reibel and Mrs. Morgan Adams of Washington Crossing State Park for some early leads on the Doans in Upper Makefield; the staff of the Spruance Library of the Bucks County Historical Society; Ruth Mahoney, Curator, Sharon Temple Museum; Jacqueline Stuart, Curator, Aurora Museum; and especially my wife, Janet Houghton Mclntyre.