Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

The Use of Primary Documents as Computerized Collection Records for the Study of Material Culture

Summary of the Project

1 During the summers of 1983-84, the Nova Scotia Museum undertook a newspaper research project which originated with the Newfoundland Museum in 1979. The original project set out to index advertisements for commodities found in nineteenth-century newspapers by way of systematically classifying and structuring the information for data entry into a computer retrieval system which would provide an inventory of goods and services available in Newfoundland for that period and which would thereby augment the documentation for the museum collections. The project was later taken up by the National Museum of Man and initiated at the New Brunswick Museum in 1982 and at the Nova Scotia Museum in 1983. Work began at the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation in 1984.

2 While the original focus and method for structuring the data were retained, the Nova Scotia Project was expanded in order that the treatment of the newspaper material would reflect the broad interpretation of "material culture" appropriate to the nature and distribution of the large and decentralized provincial collections of artifacts and sites. The project also took into consideration the enhanced capabilities of the national retrieval system presently used for artifact and specimen records. The sense of an increasing necessity to develop an integrated information matrix which makes use of this sophisticated technology to bridge some large gaps in the museum documentation of material culture was central to development of the methodology for this project. The concept of this matrix is based on an extended view of the "collection record" when "subject" within the conceptual framework of material culture is the organizing principle and where the appropriate structuring of the data for computer cross-reference and retrieval is the integrating mechanism. The following discussion outlines the basis for the approach taken in light of traditional approaches to documenting collections and the potential demand for information.

Introduction and Rationale: Expectations for the Documentation of Collections

3 In recent years the Canadian museum community has acquired an uneasy self-consciousness, shaped by the growing articulation of public and professional expectations of museums. This, at least in part, is an outcome of the rapid growth of the heritage industry and the concentrated "collecting" of the past two decades. The state of unease has been productive insofar as the development of management strategies for these typically large and varied collections has been given particular attention and support. This development of "collections management" has not only been made possible but has been accelerated through a relatively systematic, though not untroubled, application of computer technology unique to Canada.1 As well, a certain edge has been added with the growing public demand for access to collections and with increased consideration for the legal and ethical implications for "public trust." However, where "documentation" has been emphasized as a means by which collections can be accounted for and access established, expectations tor documenting collections remain unclear and the actual records for individual artifacts (which constitute the present documentation system for collections), have not as yet been sufficiently used for research or subjected to appraisal to further agitate concern. The acid test is on the horizon with the growing development of the study and presentation of "material culture" and the increasing sophistication of related research requirements.

4 The present artifact or collection records in fact reflect what has up to this point been a necessary preoccupation with the physical management or basic accounting for collections. The resulting skeletal record system provides a level of documentation which is largely descriptive and reflects "inventory" considerations for objects (identification, classification, and descriptions of physical attributes which are variable in length and complexity). To a small extent contextual information is included in reference to provenance and maker/artist biographic information. This tenacious notion of "documentation," albeit veiled by variable and indefinite expectations, presents certain and central questions: What purpose do we ultimately want the information we gather about our "collections" to serve and to what extent does it anticipate the breadth of material culture studies which museums hope to serve? Given the apparent and necessarily pragmatic limitations of artifact records, what is their purpose, how can they be augmented, and to what extent can the notion of "collection record" be extended to reflect the domain of material culture? At the practical level, and on the assumption that a "collection record" is essentially an extension of the concept of an "artifact record," how can this kind of record be structured along the same principles for the purposes of retrieval by the system which presently handles artifact records?

Limitations of the Artifact Record

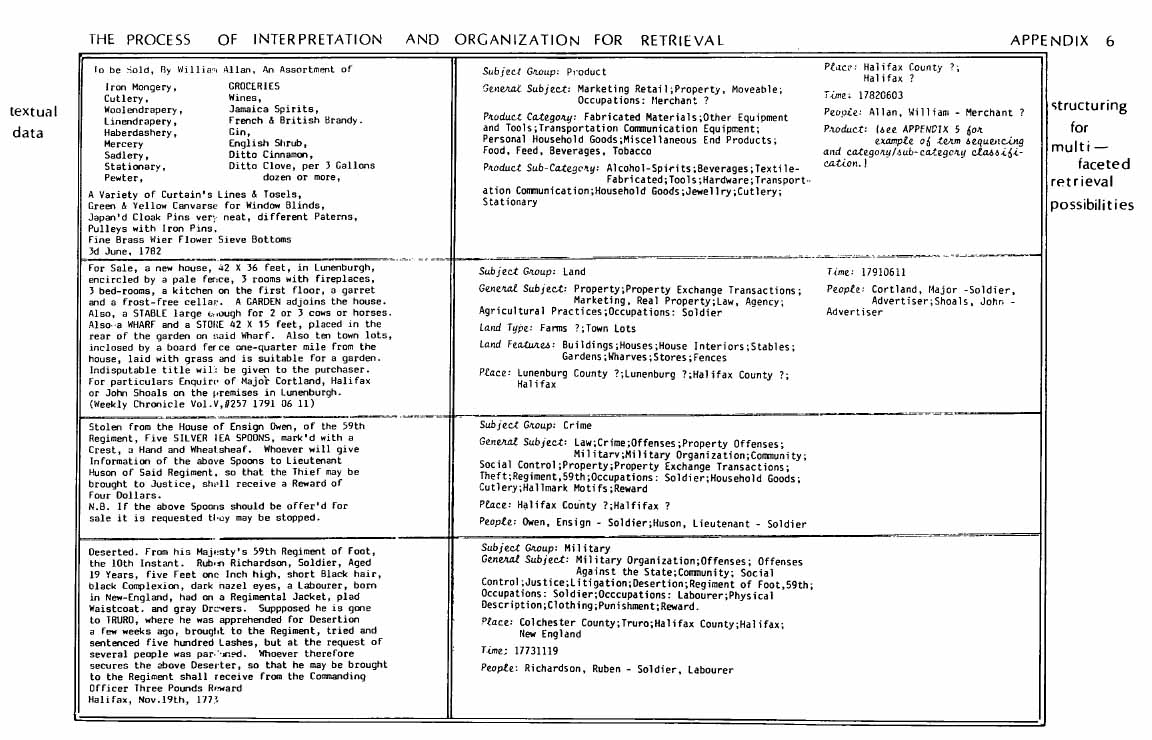

5 Research in the broadly defined area of material culture, albeit object-oriented, necessarily requires thematic or contextual amplification. For example, inventories of tools must always be considered with reference to the makers and users, the place and time of use, and to the social and economic context of their time. These inventories must, if they are to be of value to the study of the culture which generated the artifacts, refer also to the needs and the ideas which shaped them. Individual artifact records refer to specific elements of context, yet any composite of artifact records cannot reconstitute the entirety of their context. Their value is in their illumination of certain aspects of context (depending of course on the extent to which they are "complete"). In fact, in order to guarantee the reliability of the indication of context provided by artifact records, a thorough contextual framework which draws on all appropriate and available sources of information must be constructed.

6 Presently, collections of objects are documented almost exclusively through the "artifact record" — the complement of traits specific to a single object or closely related group of objects. In referring to the limitations of this type of record within the overall spectrum of information useful to the study of history and culture, it should be made clear that the inherent value of "artifact data" is not in question; rather, that the present records for collections of artifacts are limited by traditions determining their content and by the logistics of organizing information in the form of "record" for the purposes of access and management.

7 The tradition of "explaining" artifacts through their physical attributes has been aptly named the "fallacy of reductionism"2 and very much reflects a historical pattern of collecting and connoisseurship from which museums are only beginning to emerge. Here, the limitation is one of vision and institutional objective. The resulting record systems for these collections are characterized by a certain starkness which can sometimes seem exaggerated when recalled from computer files.

8 The limitations imposed by the process of generating "information"3 from so-called "unstructured" data (in this case textual data), for the purpose of creating a systematic information system, are easily outweighed by the acceleration of possibilities if the information is appropriately "structured." The process of structuring information for computer management must refer to both the way in which people actually process information (or impose organizational patterns on the seemingly random "information environment" by way of categorizing strategies) and the capability of the particular computer system used for organizing the "chunks" of information.4

9 Structuring information necessarily involves a process of interpretation and distillation where meaning is abstracted by identifying and grouping "significant elements." Where manual information systems traditionally corralled significant information components through the arbitrary structure of a "record," computers have, in a sense, undone and reassembled the traditional idea of "record," whereby the components of information are kept in a more fluid form. The initial record which organizes and structures the "raw" data can in fact be quite complex without (ideally) inhibiting the shuffling and reassembly process — resulting in a potentially vast complex of "records."

10 Back to the artifact record. While the basic documentation of artifact collections has certainly benefited from the application of computer technology (where a greater spectrum of attribute distinctions has been built into the initial record, allowing far greater possibilities for inventory comparisons and physical analysis), the possibilities for documenting and retrieving contextual associations have barely been tapped, leaving the artifact records, individually and collectively, largely incomplete.

Information Matrix Aligning Collection Records on the Basis of Subject and Context

11 The traditional approach to organizing information on the basis of the physical attributes of the "collections" has been appropriate for the practical and necessary considerations of preservation, storage, and rudimentary access (visible or physical access). This seems to be universally true for archival, fine art, and museum collections and is unavoidable given the specialized nature of these collections and the variety of material with which to contend. This approach has had a rather overpowering effect on the content of the artifact record and consequently on the balance of the resulting information system, particularly for museums where minute details of descriptive attributes have served as a kind of surrogate for "documenting" collections. The outcome of this pattern has been a polarization of information in museums, with artifact records at one side and the highly-focused, specific results of research at the other with little between. The potential for knitting this gap together by way of an information matrix which incorporates and augments the artifact record and provides prepared ground for research is now within the realm of necessity.

12 Previous treatment of this area has proved both elusive and difficult, not only because the process requires sophisticated and multi-level indexing (which would over-burden any manual system and defy maintenance), but because the process or method of approach ultimately has to be rooted in a conceptual model or system of ideas which treats the notion of material manifestations of culture and refers to the principles directing the study of culture.

13 Museums have tended to generate a variety of "records" or information files to a greater or lesser extent, as the need arises and depending on the nature and intention of the institution. These generally include an array of "raw" data collected through research (e.g., archival records, oral history transcripts, field records, pictorial files, and artifact/specimen-related data). These records have generally not been treated with the same rigour required for the automated retrieval of artifact/specimen records or, in any case, a different system generally exists for each different set of files. This is in part due to the aforementioned indexing complexities and in part because they have not been consciously treated as "collection records" per se.

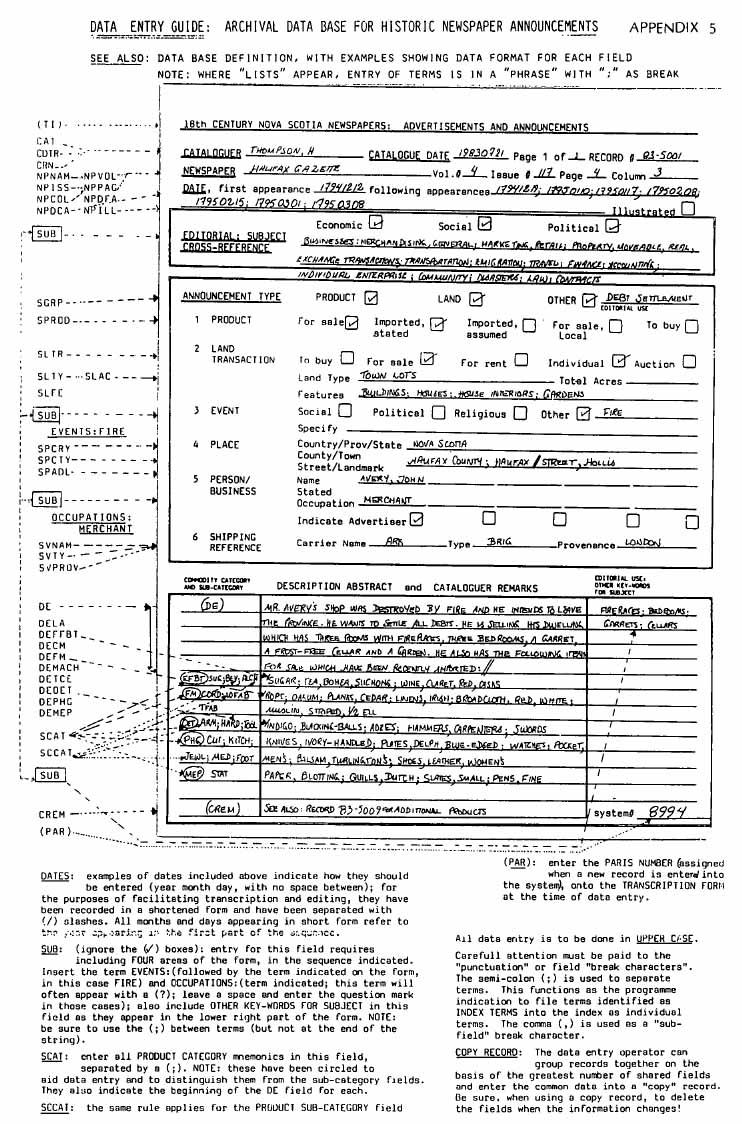

14 The assumption central to the archival project undertaken in Nova Scotia was that the principles governing the formulation of a record, conceptually and for the practical purposes of retrieval, could be consistently and systematically applied to any type of information. The project was as much an exploration in developing a method based on a comprehensive definition of material culture5 which would ensure a useful and thorough treatment of subject/content as it was an incorporation of the original intent and an adaptation of previous methods. The feeling that the museum was already attempting to maintain a large number of information files broadly related to the documentation of the collections directed the approach at the outset. The necessity of developing a method which would be useful for integrating "content" across the spectrum of files influenced the undertaking of what appeared to be another useful and potentially large and specialized harvest of information. The previous development of the project was incorporated and a broader treatment of "subject" contained by the newspaper material was emphasized.

Background: The Newfoundland Newspaper Project6

15 In 1979 the Newfoundland Museum developed a newspaper research project that attempted to deal with a number of stated problems: the underdeveloped state of material culture studies in Newfoundland, the insufficient documentation of the museum collections, and the continuous re-examination of the same archival material by a parade of researchers over a period of time. At the most pragmatic level, the need for background information relating to artifacts was seen to be most apparent in the preparation of exhibits. However, the organization of archival material, invaluable to the study of material culture, precludes ready access. Again, archival material is organized on the basis of the physical considerations of "collection" or record groups (e.g., business records, government papers, newspapers, family papers, photographs, maps). The existing manual index systems have been largely unable to accommodate research which requires access across these groups by way of an integrated subject index. To index and cross-reference all of the material on this basis, under a manual system, in any case would be virtually impossible. The Newfoundland Museum made significant inroads to previously inaccessible material by developing a transcription methodology and applying existing computer technology to a complex subject area in nineteenth-century newspapers.

16 The Newfoundland project chose to focus on extant nineteenth-century newspapers because of the large proportion of obviously material-related content. To satisfy basic questions concerning the introduction and use of imported goods as well as locally-produced goods and services, advertisements for commodities and services were selected as the focus. The project enlisted the services of the National Inventory Programme (now the Canadian Heritage Information Network/CHIN), and a recording methodology was developed to reflect primary retrieval needs as well as the nature of the technology available at the time. The museum employed students through a federal employment programme to transcribe and enter the information. Much of this material was entered and used on a previous data base and has recently been transferred to a new data base established in May 1984 by CHIN for the National Museum of Man. The data base uses the same information management system (BASIS) which has up to now been used primarily for the management of artifact data (PARIS: Pictorial and Artifact Retrieval Information System).

17 The wider application of the original project and the updating of the original data base was made possible with the adoption of this project by the National Museum of Man as part of the research programme in Atlantic history. Presently, all four provinces have contributed to the preparation of similar data for retrieval on the shared data base (Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, the Newfoundland Museum, the Nova Scotia Museum, and the New Brunswick Museum).

18 When the Nova Scotia Museum undertook this project, it was with the aforementioned considerations in mind. Previous experience with newspaper research suggested that the focus could be expanded readily given the wealth and diversity of information in newspapers for the broad domain of the study of material culture with the development of a slightly expanded recording format. Similarly, experience with the evolution of the on-line computer system (PARIS), in the five years since the inception of the project, suggested possibilities for a more comprehensive approach, specifically, the capacity for extensive indexing which has resulted in a highly flexible and multi-level cross-reference potential. In the end, the prospect of employing six students for a concentrated period of time determined the feasibility of taking a comprehensive approach.

Methodology for Indexing Eighteenth-Century Newspapers in Nova Scotia

19 The methodology incorporated three considerations: the nature of the information and its anticipated use, the capabilities of the computer system to be applied, and the characteristics of the human resource, the student employees. It took its direction from a broad definition of material culture which suggests the range of information as well as themes guiding the organization of the information. The computer system further determined procedures for transcribing/preparing the information as well as the physical organization of the information. The practical aspects of the methodology were set out in the form of specific, written guidelines for organizing, transcribing, and interpreting (editing and indexing) the "raw" data. These were formulated and revised as the project evolved. This project resulted in the recent redefinition of the data base with some rudimentary rules for data entry and guidelines for retrieval. The methodology attempted to ensure the reliability and internal consistency of the data by way of some basic management strategies which also, in the end, have helped in monitoring the course of the project for long-term planning.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Newspapers as a Source of Information

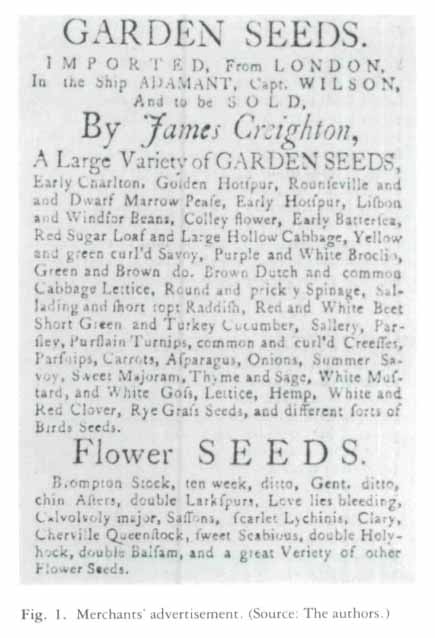

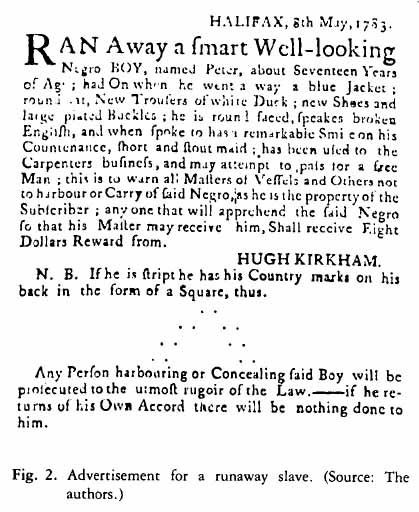

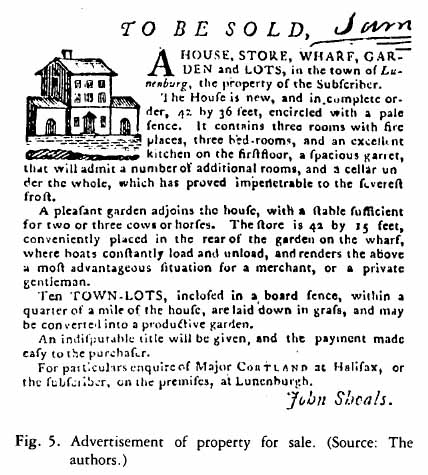

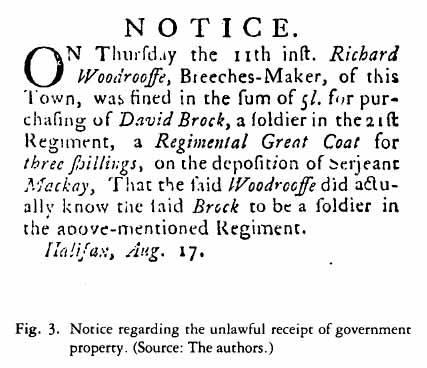

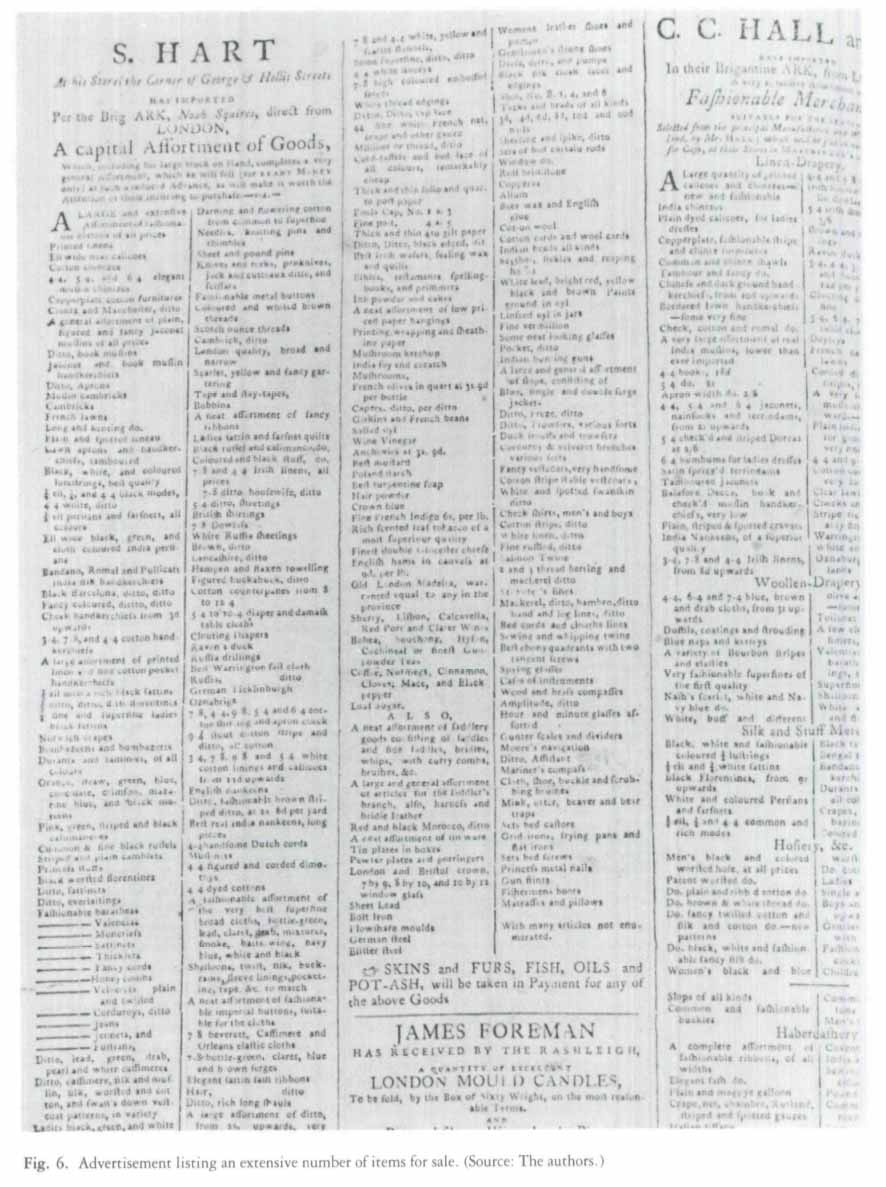

20 Of the primary written/printed documents available for the study of material culture, newspapers provide a unique and continuous source of information about time and place. Then, as now, they serve a wide public and motivate the mechanisms of communication, commerce, and to some extent, social regulation. In so doing, they provide a revealing glimpse of an otherwise inaccessible range of cultural nuances, including overall patterns of material and commercial exchange which indicate a scale of attributed value and available resources. This is perhaps most evident in the listing of commodities available (and in demand?) and other "newsworthy" notices for lost, stolen, or runaway property. Additional nuances of context are provided through a variety of other public notices for events and transactions which form the background as it were (figs. 1, 2, 3).

Distribution of Eighteenth-Century Newspapers in Nova Scotia

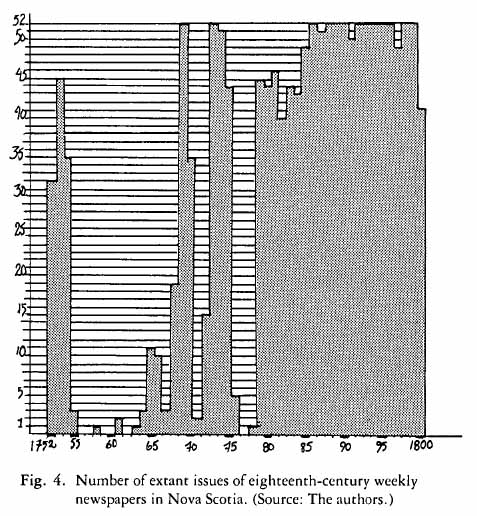

21 Previous projects in Newfoundland and New Brunswick began with the earliest available newspapers, the bulk of which were published in the early nineteenth century. In Nova Scotia, newspapers started in 1752 and a large number have survived for the latter half of the eighteenth century. As well, the rarity of existing sources of social and economic information for that period makes these newspapers particularly valuable (fig. 4).

22 Three newspapers were published in Halifax between 1752 and 1800. These newspapers were published weekly and to some extent their issues overlapped. There were also three newspapers published in Shelburne between 1783 and 1796 during the initial settlement of the Loyalist town. The total number of extant issues for the eighteenth century, including all six papers, is 1,828. The only major gap for this period appears to be between 1756 and 1764.

Content of Eighteenth-Century Nova Scotia Newspapers

23 The content of these newspapers, each four pages in length, is almost equally divided between foreign news and local advertisements and announcements; less than half a column is devoted to domestic news (e.g., shipping news, the occasional announcement of a death sentence, the celebration of a royal birthday, and letters at the post office). As almost all the local information to be found in these newspapers is contained in the advertisements and announcements, virtually all local information was included within the scope of this project.

24 The analysis of the distribution of the content of these eighteenth-century newspapers, across rough subject categories, is based on the 1,396 records completed in the course of the summer of 1983 (see Appendix 2). This represents about 16 per cent of the estimated total (288 issues) but, as the records span the entirety of the period, the following summary of the distribution of the content should give a reasonable indication of the concentration of the type of information included in the eighteenth-century newspapers.

25 The majority of the content (70 per cent), related to aspects of "exchange" or commodities for sale, including products (42 per cent), land (20 per cent), and services (business enterprises, crafts, servants, education: 8 per cent). The remaining 30 per cent related to financial concerns (debt settlement, probate administration, distribution of prize money, poor relief: 9 per cent), public events (elections, entertainment, clubs, religion: 5 per cent), transportation and communication (shipping, highway construction, post office: 4 per cent), other government activities (taxation, regulations: 3 per cent), runaways (wives, apprentices, slaves: 2 per cent), crime (2 per cent), and lost property (2 per cent).

A Systematic Treatment of "Subject" for the Study of Material Culture

26 Organizing information on the basis of "subject" is an age-old problem, one which has been tackled countless times and one which was certainly central to the development of the methodology for this project. Although there are precedents for subject classification provided by library approaches to vast collections of information, the subject distinctions are of a relatively general nature, providing an intermediate classification system where hierarchical distinctions (which attempt to group information on the basis of related concepts by way of "categories" and "sub-categories") are not used. Again, this reflects, to some extent, the manual approach to cataloguing and managing information which libraries have developed to an optimum level. However, library systems do not readily accommodate "special collections" (pictorial, oral transcripts, objects, and primary documents), partly because these collections also require a level of physical and functional classification (which books do not), as well as a consideration of the rather specific nature of the subject-matter and the extent to which it is of special interest to the study of history and culture.

27 Hence the classification of subject has been reinvented many times, indicating, if nothing else, the importance of this process to institutions which cannot readily apply the model proposed by the library system. The differences between the classification systems generated by institutions, large and small, which care for special collections, seems to depend more on the nature of the collection and/ or the subject-biases of the respective caretakers. Again, the systems tend to evolve for practical reasons rather than with a view to an overall scheme for extensive "public" use. It is not uncommon for an institution to invent more than one subject classification system, depending on the number and types of collections at hand. The reason these systems "work" for the most part is that our shared culture guarantees that the overlap of conceptual distinctions and "categories" with an array of relatively consistent elements.

28 Since its original preparation in 1937 the Outline has been widely used, scrutinized, and refined, particularly through government projects in the course of World War II, where its application to modern, complex societies required some expansion and modification. Several references to its application in a museum context have been found, both for classifying textual data and amplifying artifact records.7

29 Basically, the Outline proposes an open-ended system for classifying the consistent components of culture within seven broad categories which, to paraphrase the authors, have come to represent (through trial and error), a sort of common denominator of the ways in which social scientists and recorders of cultural data habitually organize their data. The terms used for the classification of subject for this project were the specific subject terms contained with the eighty sub-categories proposed for the distinctive components of culture. These terms were grouped, for the purpose of this project, into the very broad categories which distinguish social, economic, and political associations in order to facilitate the process of editing large quantities of data. They do not, however, function as a basis for retrieval at that level as they are too broad to be "useful" (see Appendix 3).

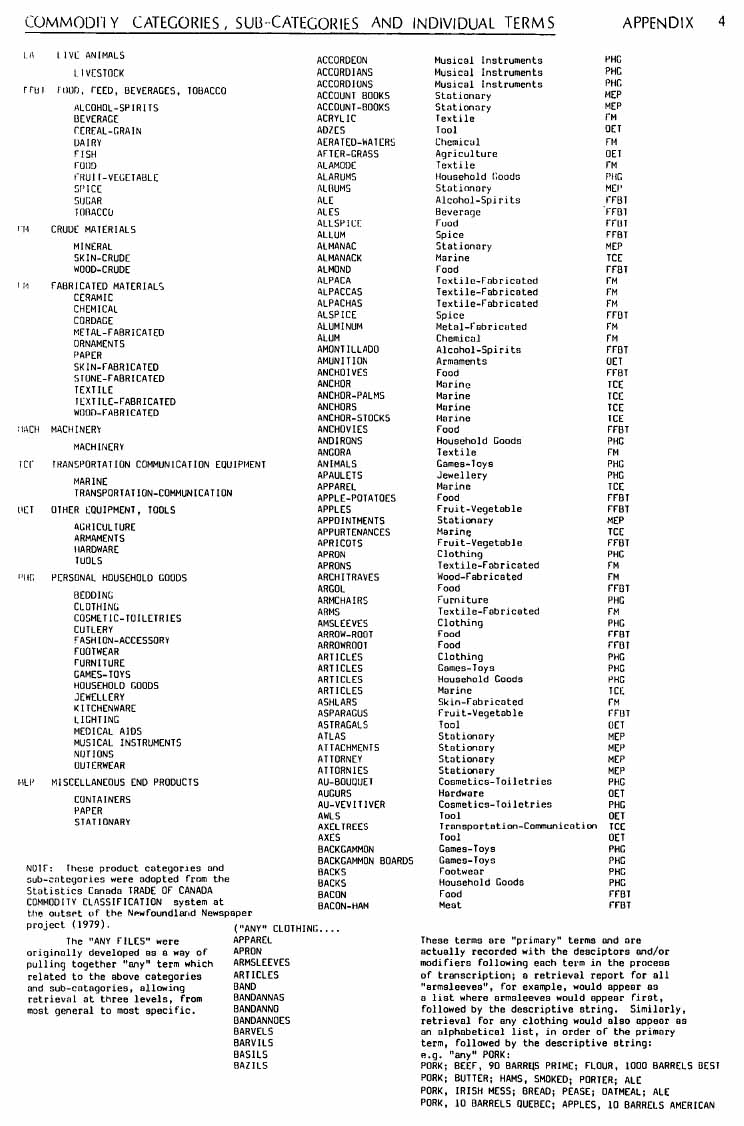

The Retrieval System and the Indexing of Subject

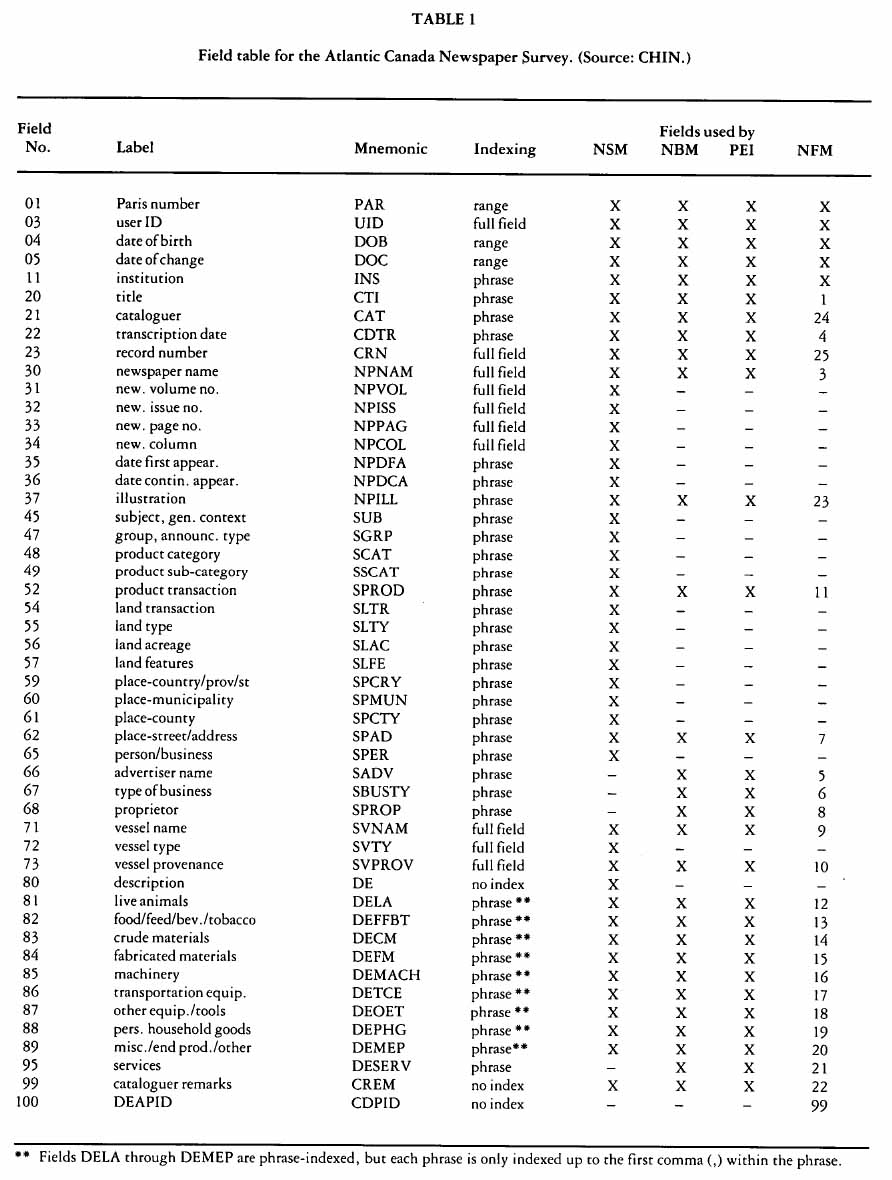

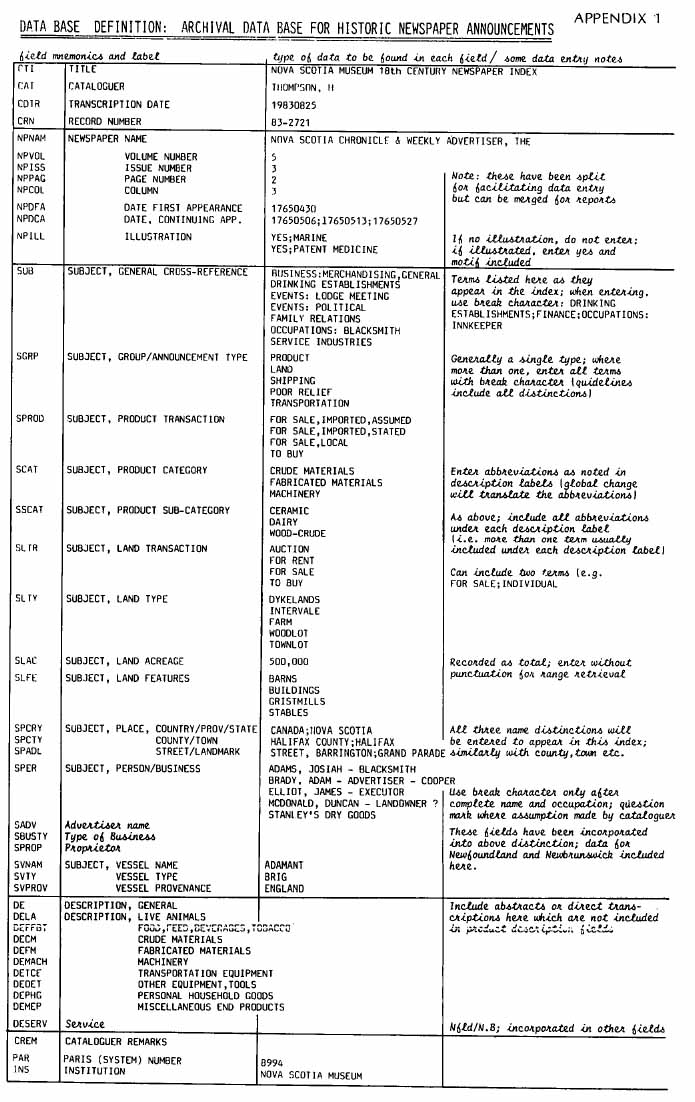

30 The system presently used for the management and retrieval of artifact data for Canadian museum and fine art collections was readily adapted for the management of archival data with the addition of "fields" or specific information files. These additional fields allow further distinction between specific areas of subject concentration (Appendix 1).

31 The principle for retrieval of information is the same for both systems. Retrieval is governed by the and/or/not rules of Boolean (set) Logic, which merge or isolate records through a process of combination or elimination of the particular elements pertaining to the question phrased by the user; the more specific the question, the smaller the document set (e.g. "find all records referring to product" will pull together about half the records on the entire data base, whereas "find all records referring to product and merchant and date 1785 to 1791" will greatly limit the relevant records).

Indexing

32 The BASIS retrieval system has a remarkable indexing capacity which allows the recording and retrieval of up to thirty-one key subject terms for any one field. The terms are recorded as a standard string of characters where unique terms are separated by a break-character (usually a semi-colon, which is added in the process of transcription and preparation of the "raw" data). The system "slots" each term into an alphabetic index for retrieval while retaining the integrity of the original string of terms within the initial record. This mechanism or system capability essentially allows a much more fluid treatment of subject.

33 As the system sorts and indexes data for retrieval on the arbitrary basis of alphabetic form, careful consideration was given to the choice of primary terms as these terms appear as isolated terms in the indexes for each field or subject-area file. Primary terms were also "pluralized" for the same reason. Modifications to Murdock's Outline were made only so far as to make the alphabetic retrieval more consistent with the demands of the system.

34 It is important for the user to be aware that this index can be browsed in much the same way as any manual index (either on-line or in printed form). The index for general subject (alphabetic), merges categories, sub-categories, and other cross-reference terms. This allows for maximum retrieval flexibility where all records for "barns" can be pulled together as readily as all records for "buildings" (the latter being the greater set, "including" barns).

35 A large part of the process of refining this kind of methodology is in the building of authority lists, which function to maintain the integrity of the index (and of the research), by defining the margins for interpretation and thereby establishing the level of consistency (see Appendix 3 for the authority list for the primary subject cross-reference structure, Appendix 6 for its application to actual records, and appendix 4 for samples of primary commodity terms).

Detail and Indexing for Subject

36 Given the capacity for accommodating a relatively large number of terms for any one record, a certain balance is required for the level or extent of detail which can be included for the purpose of the various indexes. For the general subject cross-reference index, the law of diminishing returns can apply after a point, though to a certain extent the level of detail is ultimately determined by the nature of the information. While including a large degree of detail does not compromise the efficiency of retrieval (if the data are properly structured), there comes a point where "too much" detail obscures the "usefulness" of the subject distinctions. Therefore, for any indexing task a balance must be established between the descriptive free-text data and the primary subject terms structured for index-retrieval. Establishing the balance in this case requires the essential combination of experience with historical/cultural material and an intuitive grasp of the "significant" elements of information/content for research eventualities. Too, there must be a willingness to see this process as both exploratory and developmental where decision-making is adaptive to the task of "finding what vocabulary for identifying significant components of subject-matter is relatively great.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 137 The temptation to reinvent the wheel (made all the more feasible by the large retrieval capacity for subject-index terms of the available computer system), was stalled by the realization that a complex of arbitrary cross-reference terms, no matter how well considered, would only compound the problem of retrieval.

The Subject Cross-Reference Framework

38 The framework for the subject cross-reference system developed for this project was based on the Outline for Cultural Materials,8 originally developed under the direction of George P. Murdock. The Outline facilitates interdisciplinary research in the social sciences by way of providing a classification tool which can be applied to the contextual data assembled for the Cross-Cultural Survey Files (later the Human Relations Area File). Although the classification system was originally developed from a sample of widely varying cultures, it was based on the assumption that all information about culture falls into universal works" rather than compelled by original "rules." One of the great advantages of computer applications to this whole area of "subject-indexing" is the ease with which "corrections" or refinements can be incorporated (if consistency has been firmly established at the outset).

"Field" Distinctions for Subject within the Archival Data Base

39 In order to simplify retrieval and at the same time allow the most comprehensive indexing of the content of the newspapers, the following fields for subject were established (Table 1; see also Appendix 1).

SUBJECT, GENERAL CROSS-REFERENCE (SUB)

40 This field contains the general subject cross-reference terms provided by Murdock's Outline (Appendix 3), as well as specific primary or "key" subject terms. It does not include the commodity terms or categories, the land type or feature terms, or the place or people names. These all form distinct and fairly large concentrations of information and have therefore been given their own files or "fields." The general subject field does, however, include the following three distinct clusters of information: occupations, events, and business; the consistent use of these terms (followed by ":" and the specific terms), allows a sort of "sub-field" distinction without further fragmenting the field structure of the data base.

SUBJECT, GROUP/ANNOUNCEMENT TYPE (SGRP)

41 This field contains the index terms for general type distinctions which allow a rudimentary physical grouping of records for initial classification. The terms are assigned from a limited authority list based on the most obvious aspect of the content of the various types of announcements (Appendix 2). They have been used primarily as a convenient sorting mechanism for the interim manual system and have been retained to pull together the larger document sets where this single-level distinction is useful.

SUBJECT, PRODUCT TRANSACTION (SPROD)

42 This field provides for the distinction between products offered for sale and requests for the purchase of goods and whether, in the case of goods for sale, they are stated as "imported" or whether an assumption is being made. The distinction is also made between local goods for sale or purchase, although advertisements for these appear much less frequently. The authority list for these retrieval terms is limited and all terms are included in the samples provided in Appendix 1.

SUBJECT, PRODUCT CATEGORY (SCAT); SUBJECT, PRODUCT SUB-CATEGORY (SSCAT)

43 These categories and sub-categories were adopted from the Statistics Canada Trade of Canada Commodity Classification system at the outset of the original Newfoundland newspaper project (Appendix 4). The nine broad categories cluster the very dense and lengthy lists of commodities and the sub-categories allow the necessary finer distinctions which are ultimately more "useful" for retrieval.

SUBJECT, LAND TRANSACTION (SLTR)

44 As with product transaction, this field indexes the type of transaction for the land advertised, allowing distinctions to be made for land sold by individuals or by auction, property for rent or requests for purchase.

SUBJECT, LAND TYPE (SLTY)

45 The terms chosen here form a limited authority list and are contemporary to the eighteenth century (dykeland, farms, intervales, islands, island lots, marshes, outlands, town lots, undivided lands, unimproved lands, uplands, wildlands, and woodlots).

SUBJECT, LAND ACREAGE (SLAC)

46 This is a numeric field and includes the total number of acres referred to in any given announcement.

SUBJECT, LAND FEATURES (SLFE)

47 All references to building types and other features described in the advertisements are listed for this field. Where there is a reference to a building both the term "building" and the specific name are used. Some examples of the types of terms to be found are: bake ovens, barns, blacksmiths' shops, buildings, fences, gardens, grist-mills, houses, house interiors, orchards, outbuildings, outhouses, sawmills, stables, stores, taverns, warehouses, and wharves.

SUBJECT, PLACE: COUNTRY/PROVINCE STATE (SPCRY); COUNTY/TOWN (SPCTY); STREET/LANDMARK (SPADL)

48 Place data are added to all three fields where possible. Twentieth-century names have been used with the hope of serving a broader use and on the assumption that historians would be familiar with both the historic and modern names. Where "landmarks" are referred to, both the modern and the original term are used (if known). Place remarks included in the text are often rich in nuance and detail and, other than using the concept of "landmark," are difficult to index. Abstracts of this type of free text have been included in the general description field (DE).

SUBJECT, PERSON/BUSINESS (SPER)

49 All names included in any given announcement are recorded, followed by the occupation and an indication of whether these associations are stated or assumed (e.g., Smith, Adam — carpenter; or Smith, Adam — carpenter?). References to any or all occupations can readily be pulled together through the general subject index (occupations: carpenters). Note: for the eighteenth century, "occupation" tends to be a more useful term than business, although "business" is used where a safe assumption can be made. A person advertising goods for sale was not necessarily a merchant, nor, if the goods were dry goods for example, did this person have an established dry goods business. This situation, of course, changed as the town became more established and certainly the occurrence of established businesses in the nineteenth century is more frequent.

SUBJECT, VESSEL NAME (SVNAM)/TYPE (SVTY)/ PROVENANCE (SVPROV)

50 Most of the goods are listed with reference to the name of the ship and her provenance. This information becomes particularly useful for establishing trading patterns over time.

The Commodity Index

51 The bulk of the information recorded (40 per cent) for the eighteenth-century newspapers is in the form of long lists of "goods" or products advertised for sale. The focus of the original project in Newfoundland and later New Brunswick was concerned with classifying and transcribing these lists into a retrievable format; that is, it had to be structured into manageable components where secondary terms followed primary terms, broken with appropriate punctuation. This trade-off, where the recording sequence isolated the primary term from the nuances of context, resulted in a certain disfiguration of context, albeit unavoidable. The decision-making process becomes rather complex when the "descriptor" actually modifies the meaning of the primary term or where it is unclear which term the descriptor is modifying (e.g., "French cambricks and long lawns," "men's black and colored worsted hose"). As a result, an exacting sequence for recording the commodity terms was developed in order to establish a level of consistency and minimize the margin of interpretation (Appendix 6).

Management Mechanisms for Ensuring the Reliability of the Data

52 Central to the methodology for this project was the task of ensuring the reliability of the data. This meant the establishment of mechanisms to ensure as much as possible the accurate and consistent preparation of the data. These primarily took the form of written guidelines which were refined in the course of the project and resulted in part from the lack of documented reference points at the outset of the project. Awareness that the preparation of the data was to be done by university students with relatively little experience with archival material, let alone long hours on microfilm readers, directed the form the guidelines took. The "rules" set out, above all, to ensure a standard approach to the information by way of transcription procedures and classification parameters. As well, in order to ensure that all the material was covered, students were required to keep track of the number of ads contained in each issue and the number of ads recorded in the course of the day. This also served as an indication of the overall volume and the time that could be expected to completion.

Conclusion

53 This paper has described in some detail a specific organizing approach to a body of raw research data. This information, derived from newspapers and not usually considered as part of the contextual information directly relevant to artifact record, is important in the larger arena of material cultural studies. The ultimate value of this information depends both on completion of the project and upon testing of the usefulness of the structure of the data through actual research demands. In the meantime we note that this project has emphasized the necessity of clearly examining the assumptions and methods used in the past to document our collections. Through this process we have extended the concept of collection records to include and to structure systematically an enlarged range of research data that will result in a broader interpretation of material culture and enhance the study of our museum collections.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6Debra McNabb

APPENDIX 1

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7APPENDIX 2

APPENDIX 3

APPENDIX 4

APPENDIX 5

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11APPENDIX 6

(Editorial Note: The project described in this paper forms part of the Atlantic Canada Newspaper Survey, various elements of which have been the subject of previous communications in Material History Bulletin. Original plans anticipated a third summer's work in 1985, taking advantage of the federal government's Career Oriented Summer Employment Programme for university students. The pressure of regular activities, however, will prevent the Nova Scotia Museum from participating as expected, and the work will be put on hold. It is hoped that work in other provinces will continue insofar as the National Museum of Man is, itself, able to sponsor the programme or as resources in various provinces permit.)