Reviews / Comptes rendus

Newfoundland Museum, "Business in Great Waters"

1 Dating from the 1840s, the Murray Premises consists of a group of connected mercantile buildings on the St. John's waterfront. They were rescued from redundancy and demolition by a local developer who, with federal assistance, turned them into a St. John's equivalent to the Historic Properties at Halifax. They contain offices, shops, a superior liquor store, a restaurant, and now a branch of the Newfoundland Museum which has taken over four rather small floors at the east end. The first major gallery to be completed is dedicated to "Ships and Shipping in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1500 to the Present."

2 It is an excellent idea to place a museum in a downtown shopping area which is itself part of the city's heritage: it becomes immediately accessible to the "passing trade," as shopkeepers say, rather than an institution demanding a special visit. The museum's designers have taken this into account in planning the first floor, making it open and attractive to those walking by. It is a pity that it is not more extensive. Casual visitors may be deterred from browsing any further by the stairs which lead, via a temporary exhibition on Elizabethan England (which will be replaced by a permanent natural history display) to "Ships and Shipping" on the third floor. This is to be regretted, since the climb is worthwhile.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

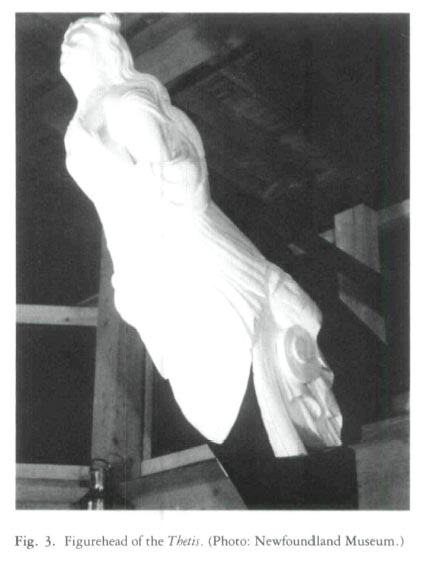

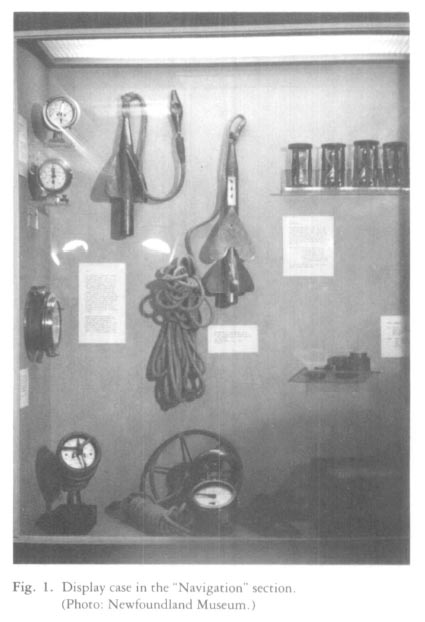

Display large image of Figure 23 The curator of the display had to work within a number of serious constraints. First, the floor space is limited and broken up by a multitude of posts supporting the low ceiling. Second, the collection to be displayed was uneven. There was, for instance, a plentiful supply of navigational instruments, ship portraits, steamship models, and general odds and ends, but not much on sealing or to do with the common seaman. Third, the museum staff felt that they had to find space to display artifacts from the important Basque whaling site at Red Bay, Labrador. The task was to turn an awkward space and an awkward collection into a coherent exhibition of Newfoundland's maritime heritage.

4 Certain exclusions were decided upon at the outset. The cod fishery would be dealt with by another branch of the Newfoundland Museum at Grand Bank, on the Burin Peninsula: thus there was no need to say much about the principal article of export. The import trade could be omitted, since its nature was already adequately represented at the Museum's Duckworth Street location. At the Murray Premises the concentration would be on ships, shipping, and trade.

5 Nevertheless, there are three sections of the display which are arguably anomalous. One has been mentioned already: the Red Bay Basque material. The section itself is clear and well-done, but it has little to do with Newfoundland trade and shipping. It deals with the exploitation of a single resource by European fishermen in a finite and early period. However, it was necessary that the material be made available, and this was the only possible location. Likewise, the section on the seal fishery fits uneasily. Sealing had a lot to do with shipping, and that aspect is emphasized — the display is dominated by models of the Bonaventure and Adventure, bought for the fishery in the early twentieth century — but since it was, like the cod fishery, a resource industry, it should be elsewhere. Indeed, one hopes that in time the museum will find the space and the money to provide a fitting memorial to an ancient industry hit on the head and left to die by a militant and ill-informed animal rights movement. The collection of navigational instruments, complete with a binnacle, has been turned into a display illustrating the development of navigational techniques. This has considerable intrinsic interest, but it is the only technical section in the exhibition. There is nothing, for instance, on shipbuilding or seamanship.

Display large image of Figure 4

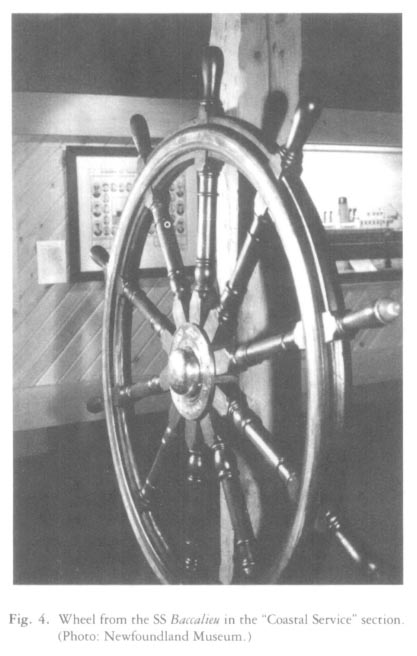

Display large image of Figure 46 The rest of the gallery deals more directly with the major themes. There is a merchant's office, as of 1938, littered with papers and period objects, looking out over the harbour. Panels and display cabinets cover the fish trade, the sailor's life, the master, the coastal service, shipwrecks, and marine archaeology. There is an interesting series of sixteen portraits of sailing vessels; a guide to sailing rigs; a ship's bell; a wheel and bridge telegraphs. All these sections — as well as those mentioned above — have been assembled and designed with imagination and sensitivity. The research has been thorough, and as a result the information is clearly and accurately presented without overloading the visitor with detail. Objects, maps, texts, and illustrations work well together. The overriding impression is that a remarkable range of subjects has been covered in a confined space without clutter. For that achievement, the curator and museum staff deserve congratulations.

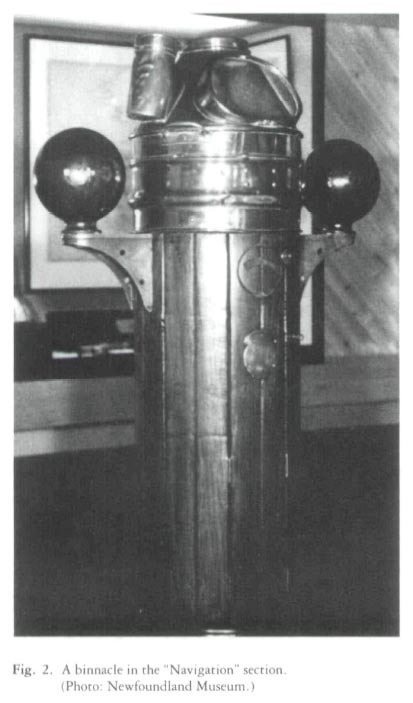

7 The imbalances in the exhibition reflect the strengths and weaknesses of the collection. There are several models of steamships, for example, but none of schooners or the old "wooden walls" that used to prosecute the seal fishery. There is plenty on navigation, but relatively little on the seaman's life. What is needed to compensate for this is a booklet providing more information on the nature and development of the Newfoundland fish trade and its attendant shipping. But overall the exhibition is a success. Victoria Dickenson and her staff have dealt intelligently within difficult constraints to produce an exhibition which no visitor to St. John's should miss.

Curatorial Statement

8 The Newfoundland Museum has always maintained a maritime collection and gallery. The previous "Maritime Gallery," which consisted chiefly of ship models and parts, was closed in 1980 in preparation for construction of the new Murray Premises exhibits. It was decided at that time that one of the exhibit floors would contain the maritime collection. A distinction was made between artifacts associated with trade, ships, and shipping, and those associated with the fishery. The technology of offshore and inshore fishery is explored at the Southern Newfoundland Seamen's Museum in Grand Bank. The Murray Premises exhibits could reflect the business end of the fishery — the province's mercantile history.

9 An examination of the collection produced a few surprises. The larger artifacts have been on display for many years — ship models, ship wheels, binnacles, telegraphs — but hidden away in storage was a fine collection of navigational instruments, including some early eighteenth-century material, plus a collection of some sixty water-colour and oil portraits of vessels connected with the Newfoundland trade.

10 The nature of the collection dictated the outlines of the exhibit. Trade is an abstract concept. To describe the economics of the fish trade, the rise and fall of merchant houses, currency problems, etc., would be difficult to encompass in a museum exhibit without resort to a large number of visual aids — charts, graphs, or maps. It was decided instead to group the artifacts in a natural order and to develop themes from these groupings. Visitors would be able to view each set as a coherent whole and would not be required to follow a predetermined path through the exhibit. These theme groupings would, however, be connected not only in content, but also through the use of a "by-line" designation in the graphic components. For example, all the groupings dealing with the fish trade were identified by the by-line "The Fish Trade" across the top of the panels.

11 In addition to considerations of the collection's content, the curator also had to recognize the "traditional" value of some individual artifacts. The ship models had always been on display, not as part of a theme grouping, but almost as objets d'art. The figurehead of the Thetis, a well-known local vessel, required a home. The gold watch presented to the saviour of the Florizel was a well-remembered item, as was the ship's wheel from the steamer Baccalieu. Certain considerations of local history also influenced theme-grouping choice. Sealing has long been a Newfoundland tradition, and with the current controversy regarding the seal hunt, some historical perspective through a display was deemed necessary. The recent discoveries associated with the Basque whaling industry at Red Bay, Labrador, demanded exhibition because of local as well as international interest in the site.

12 Taking these factors into mind the exhibition was composed of group exhibits in the following manner:

The graphics are a major indicator of theme groupings. Each grouping is introduced by a large panel with by-line, title, text, and line-shot (high contrast photograph) or engraving, silk-screened on arborite. All such introductory images are identified as to title and source.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 513 Integral to the planning of the exhibit was its future use as a teaching display for school classes. The rigging diagram, for instance, is geared to school use for ship identification. (The panel also houses a film screen for short film presentations to classes.) In "The Master" exhibit, a contemporary chart is laid on a "chart table" under plexiglas, so that it is accessible for classes in plotting a course. The "Merchant's Office" is an excellent teaching piece; 1938 was the year the first freezer plant opened in Newfoundland — a death knell for the salt fish trade. The first classes will be under way in February 1984.