Articles

"Canadian Ways":

An Introduction to Comparative Studies of Housework, Stoves, and Diet in Great Britain and Canada

En s'appuyant sur des dossiers du ministère de l'Immigration relatifs à la formation des domestiques britanniques à la vie canadienne, au cours des années 20, cet article établit une comparaison entre les fourneaux de cuisine, l'alimentation et les travaux ménagers tels qu'on les connaissait en Grande-Bretagne et au Canada. Il établit aussi d'autres comparaisons au moyen de documents et d'illustrations datant de la fin du XIXe siècle et du début du XXe. Enfin, il remet en question l'idée communément admise selon laquelle la culture matérielle domestique et le comportement face au travail domestique aient été essentiellement les mêmes au Canada et en Grande-Bretagne et insiste sur la nécessité de recherches comparatives systématiques en la matière.

This paper compares cooking stoves, diet, and housework in Britain and Canada, focusing on evidence in Department of Immigration files on the training of British domestics in "Canadian ways" during the 1920s. Other comparisons are drawn from some late nineteenth and early twentieth-century printed and pictorial sources. The paper questions common assumptions of essentially similar domestic material culture and work patterns in Britain and Canada and calls for systematic comparative research in this field.

1 The stimulus for this paper came from reading Marilyn Barber's article "The Women Ontario Welcomed" in the September 1980 issue of Ontario History.1 Among other things, it described the Canadian government's experiment between 1928 and 1930 in supporting training centres or hostels run by British authorities in the United Kingdom for women who would take up domestic service in Canada, as well as in Australia and New Zealand (fig. 1). The demand for these immigrant domestics was expected to be brisk, as these women (or "girls") who opted for Canada were supposedly trained in "Canadian ways" and on Canadian household equipment, some of which was installed in the hostels at the Canadian taxpayer's expense. What were these Canadian ways? What equipment and teaching aids were called for? What difference did it make, or how did housework and household equipment change when the Atlantic was crossed?

2 This paper will not attempt a grandiose thesis or ultimate conclusion about housekeeping in Ontario or "Canadian ways. "Instead, it is intended to encourage some comparative studies of domestic material culture — not only in the context of different nationalities, but different regions and locales, as well as ethnic and socio-economic groups in Canada. Its focus is the comparisons drawn between Britain and Canada in the training hostel record of Department of Immigration files, supplemented by material derived from late nineteenth and early twentieth-century printed, pictorial, and manuscript sources. Though the hostel training included needlework, cleaning, and so on, the two main areas of comparison drawn in the record and in this paper are stoves and food (which, of course, have intimate connections with domestic work), along with a few observations on "labour-saving" devices.

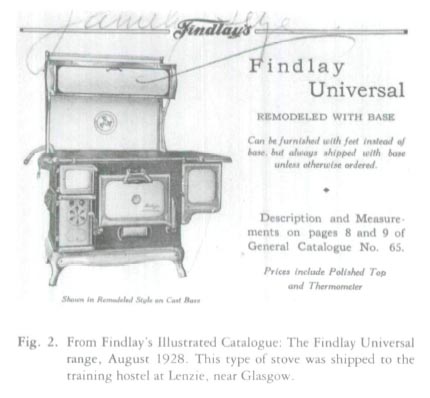

3 No domestic equipment on which these immigrant domestics were trained reached the importance in the record assumed by the cooking stove. "Canadian ways" did not necessarily mean cooking on an electric stove by this time, and electric stoves were not considered a special prerequisite for the hostels with sufficient electrical power. Two stoves were purchased and shipped from Ontario at the Department of Immigration's expense to equip the hostel at Lenzie, near Glasgow.2 Neither was electric — one was a Findlay Brothers Universal six-hole steel range, the other a Moffat's Blue Star Gas range (fig. 2). Were the expense, delay, and probable difficulty with repairs and spare parts worthwhile? Were there not any cooking stoves available in the United Kingdom similar enough to Canadian models to serve the purpose?

4 Before providing an overview of the stove options available, it is of interest to detail the rest of the cooking ranges with which the training hostels were equipped. Trainees at Newcastle could use an electric stove, "English make," an English kitchen range, set in, an English gas stove, and a Canadian Gurney coal and wood range, the latter donated by "an interested Canadian." For the Cardiff hostel a small electric stove "for demonstration purposes only" was recommended. The hostel was equipped with "an ancient gas stove" with four burners, an oven, and a large copper boiler attached, along with an English "kitchener fire place with two ovens." The trainees at the Portobello Road hostel in London could become acquainted with a Canadian wood stove and "the ordinary coal range," while those at Market Harborough, London, used a "kitchen range" (valued at £24.5.2), an "Australian stove" (worth £4.17.7), and a hot plate.3

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

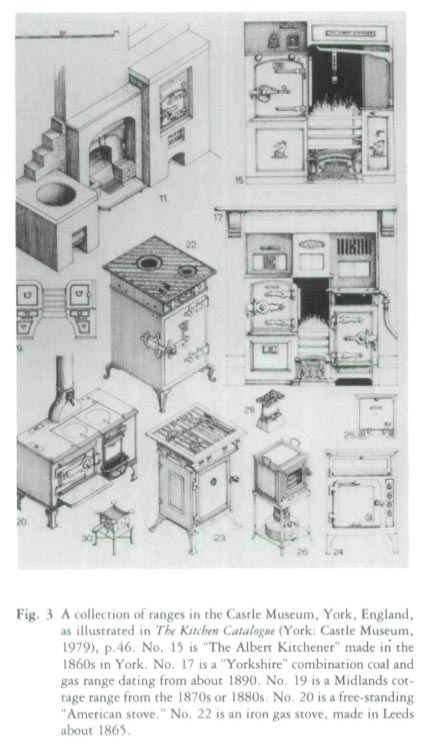

Display large image of Figure 25 Before ordering the Findlay and the Moffat ranges, the Department's Mrs. Charlesworth, who was stationed in the United Kingdom, had been shopping for cooking stoves. She did not describe those she came across, but evidently they were not satisfactory to her. The average Briton's preference in cook stoves was also regretted in a 1922 British fuel research board report (fig. 3). It noted:

The report calculated that an open range used at least 66 per cent more fuel than a closed one, and presumably involved 66 per cent more work keeping it lit, at least for those which burned solid fuel.

6 Though the report saw the presence as wholly irrational, two factors may have contributed: open ranges could roast roasts (rather than bake them in an oven) and the open ranges were easily accommodated in fireplaces in houses built long before.

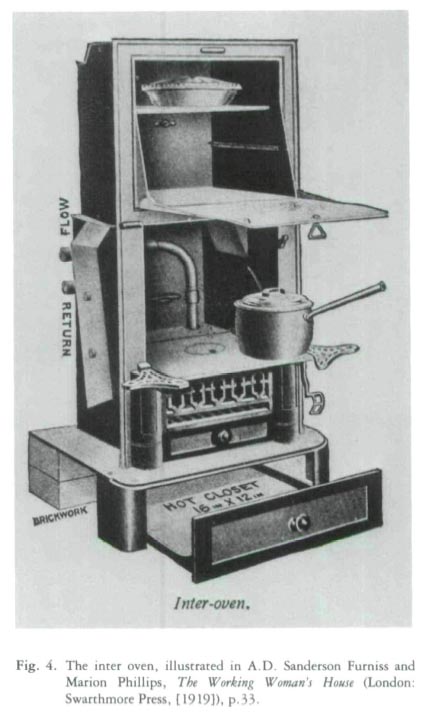

7 But the type could also be found in newly built houses, it seems. Figure 4 is from The Working Woman's House, a 1919 Labour party publication. The inter oven, found in "all homes in Welsh garden villages," is offered as a model to replace "the large kitchen range with its much unnecessary work for the morning hours."5

8 Not all ranges in Yorkshire were Yorkshire ranges, of course; neither were all open ranges Yorkshire ranges. In her 1861 Book of Household Management, Mrs. Beeton does not refer to the three "modern" open ranges she illustrated as Yorkshire ranges (fig. 5). Of these, number 3 was the simplest and cheapest, number 4 was identified as the "Improved Leamington Kitchener, first prize winner at the Great Exhibition of 1851," and number 5 as "another Kitchener, adapted for large families."6

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 39 The closed cooking range was by no means unknown in Britain. According to the catalogue of the Castle Museum, York, the free-standing American stove, introduced in the 1840s and still available in the 1930s, never achieved in Yorkshire, at least, the popularity it enjoyed in Scotland.7 Perhaps more severe winters were a factor. Other northern peoples, including Swedes, Germans, Russians, and Chinese, had long appreciated that closed stoves provide more warmth in a room than an open fire if the room is relatively airtight.8

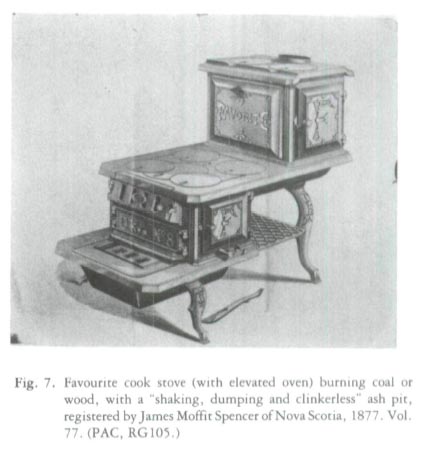

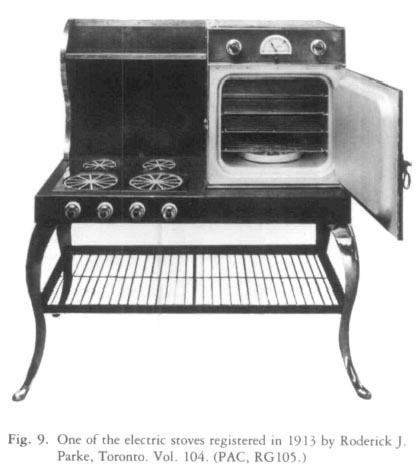

10 A wealth of information on late nineteenth and early twentieth-century cooking stoves made and used in Canada can be derived from registered industrial designs.9 Figures 6-9 illustrate some of the cooking stoves registered. These designs were all of a "closed" variety and are one of the most numerous and consistent domestic artifacts in the record. (Legal protection from infringement was offered to new designs, at least fifty examples of which were to be produced by an industrial process. The appearance of the stove was the issue, not its workings or implicated patentable devices, though several makers offered explanations of these, along with copious high quality illustrations.)

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 611 Two examples were found of nineteenth-century testimony comparing such Canadian models to English stoves and acknowledging how the former affected domestic work. Anna Leveridge, writing from the Ontario backwoods in 1883, commented: "A piece or two of wood in the stove casts as much heat as a large fire in our English ones. When I have a fire large enough to bake with, we can hardly bear ourselves near it."10 Canadian stoves were superior in other respects according to an experienced English domestic working at Cannington Manor (then in the North-West Territories) in 1892. She wrote to another domestic back home: "The stoves are much better than in England. They have a fall top an [sic] just a pipe to carry the smoke. They are so easy to clean I can Blacklead it easy in 10 minutes. No one listens to hear me clean the flues."11

Display large image of Figure 7

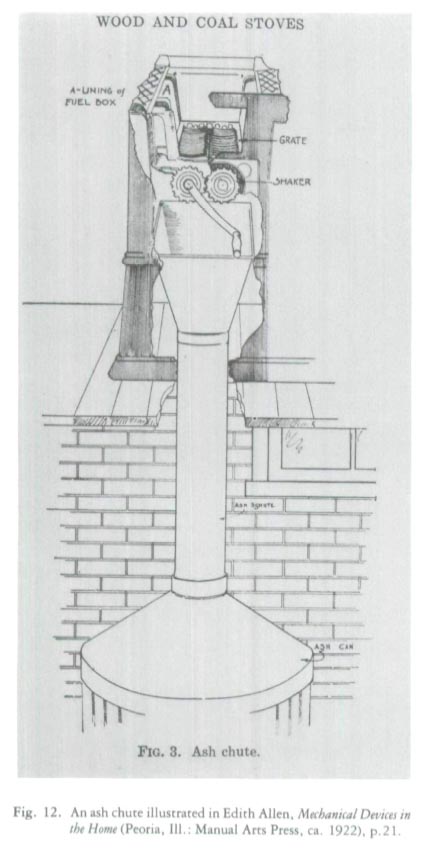

Display large image of Figure 712 It was calculated in a Boston Cooking School experiment in 1899 that the care and maintenance of a coal stove demanded almost an hour a day, including blacking, sifting, and emptying ashes, carrying coal, and laying and tending the fire.12 Another experiment at Purdue University in 1936 calculated three hours a week for the care and cleaning of a wood and coal range (compared to twenty-six minutes for an electric stove and two hours for a gas range.)13

13 Most English domestics and housekeepers were not likely to be familiar with the care and feeding of a wood stove. It differed, in the main, from a coal stove in that coal burns longer and hotter, though it is dirtier to handle. Coke — evidently in general use in Britain in the period in question and not mentioned in Canadian sources consulted — involved more work than wood or coal, being difficult to ignite, easily extinguished, dirty, and containing a considerable proportion of incombustible ash.14 Another dirty solid fuel, involving a greater volume of work, was peat, likely more extensively used in Britain than in North America.

14 But the labour-intensive aspect of a solid fuel range, along with the dangers and dirt involved in lighting it, splitting wood and breaking coal, and the proximity of people to an intensely hot free-standing monolith — these should be seen in the context of an appliance that can accomplish several tasks simultaneously and without additional cost — qualities evidently of no interest to modern manufacturers. In addition to their cooking, baking, and broiling functions, solid fuel cook stoves heat rooms, water and irons, help to dry clothes, and keep food warm. Of course, they also heat rooms in the hottest weather, and demand about the same amount of effort to effect just one thing — such as heating water or a pot.

15 Another compensation is that a solid fuel stove provided a focus for family life and its crackling flames a measure of entertainment. Open fires did not lose all appeal on this side of the Atlantic, as can be seen in the mica windows of heating stoves and the popularity of the fireplace. Even Dr. Helen MacMurchy, whose series of nationalistic pamphlets on Canadian domestic life rarely fail to sound the gong of scientific household management, was susceptible: "Could you not have a little open fire in the kitchen (in addition to the kitchen stove) and in one or two other rooms?... Hearth fires help to make good children."15

16 Dr. MacMurchy referred in How We Cook in Canada to an electric stove as "a fine thing, very clean, not even a burnt match to put away...and has even heat." She added the proviso, "Buy a Canadian one, of course and arrange about getting necessary repairs and renewals before you buy."16 The last clause provides damning testimony, corroborated in other sources, that in this period many electric appliances were not exactly God's gift to women. They had a penchant for burning out and breaking down, the stoves were sensitive to spills and corrosion, were not easy to get repaired,17 and were not much fun to sit around either (see fig. 9).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 817 An electrified house did not necessarily have an electrified range. At least in the United States in the 1920s, they were low on the list of popular electrical appliances, after irons, vacuum cleaners, and curling irons.18 In the United States in 1929 more than 8 and 13 million homes, respectively, used coal and wood and gas stoves while only 725,000 used electric stoves.19 Sixty-eight per cent of American dwellings were electrified in 1930 (though only 10 per cent of the farm houses). That figure was 35 per cent in 1920, when about a fifth of British dwellings had 20 electricity.20

18 Cooking with gas seems to have been more prevalent in North America than in Britain (see fig. 10), where gas stoves did not proliferate until the 1890s or later. The Fuel Research Board report regretted that the technology had advanced so slowly, and the English gas stoves had not changed much in thirty years. Its author asserted that the only reason gas was not used more was its great cost. Its disadvantages were deemed to be imaginary or due to carelessness on the part of the housewife.21 By contrast, a 1920s American manual on mechanical devices in the home considered gas to be "the cheapest fuel to be had at the present time," a labour-saver as "it makes so little dirt," and "a safe fuel in most hands." It did offer complicated instructions on using a gas range and mentioned the risk of an explosion blowing off the oven door and engulfing bystanders in flames.22

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 919 According to a 1913 immigration pamphlet, Woman's Work in Canada, a gas cooker could be found in "nearly every well appointed house, but... used only as an assistant cooker." The cast iron nickel-trimmed Canadian range, with its six covers, large ovens, and wide heaters, was the real workhorse and "one of the first surprises an English girl gets when she enters the kitchen."23 Whether the first statement is true, and when or whether gas stoves outnumbered solid fuel ranges in Canada was not determined. How We Cook in Canada did not say very much about gas stoves, only: "There are many parts of Canada where we have natural gas or manufactured gas and then a gas range has many advantages. There are also combined gas and coal ranges" (fig. 11). 24

20 The training hostel record does not provide much evidence either on Canadian norms regarding cooking with gas. It infers that, at least in Toronto, solid fuel ranges were quite passé. A request for another Findlay stove for the Cardiff hostel from its superintendent, enthusiastic to adopt "Canadian methods," was turned down. Reasons given were that the hostel kitchen was too small and that it was unlikely that the trainees would need such a stove as they all proposed to go to Toronto. "I understand," added the official, "most of them are familiar with the use of oil stoves."25

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1021 The familiarity with oil stoves on the part of the trainees does not mean that they were urban sophisticates. On the contrary, in Britain, oil cooking was mainly confined to cottage homes, according to Lawrence Wright's Home Fires Burning.26 This type of appliance was barely mentioned in Canadian sources consulted. Mechanical Devices in the Home, a 1922 Peoria, Illinois, publication, describes them as "designed for the comfort of the woman who cannot have a gas or an electric stove." It continues with a chronicle of cautions and risks of calamities which make a time bomb seem more attractive to have around.27

22 While cooking stoves were the equipment especially absorbing to departmental officials concerned with the training hostels, the most important "Canadian ways" to communicate involved Canadian cooking. It is difficult to assess from this record exactly how Canadian and British cookery differed, as it is clear that very few of the trainees had ever been exposed to middle-class cookery. They had a great deal to learn — not just "Canadian ways." Still, there are numerous (undisputed) statements in these records, as well as in others, by the domestics, their employers, and Immigration officials, to the effect that Canadian diet differed from what was generally found in Britain.28

23 Much of the difficulty in communicating these differences to the trainees stemmed from the near absence of cooking instructors with Canadian experience at the hostels. At Lenzie one instructor with Canadian experience was totally undisciplined and hard to get along with, in Mrs. Charlesworth's view. The instructor at Newcastle, she sniffed, had never been to Canada but "thinks she knows a lot about it because her sister visited there a few years ago.29

24 Still, the Department was determined and canvassed around for appropriate Canadian cookbooks. Two titles were selected: The Five Roses Cookbook — described as "a good standard cookbook for Canadian cooking and widely used in Canada." Perhaps the best evidence of this is that twelve of twenty-five copies sent over disappeared from Canadian Emigration offices. Nellie Lyle Pattinson's Canadian Cookbook — still in print in a revised edition — was the other. It was recommended and used as a text by MacDonald College, and by the Women's Institutes' cookery demonstrator at the Canadian National Exhibition.30

25 The Five Roses Cookbook obviously contains, in large part, recipes using flour.31 The trainees may have concluded that waffles, cookies, pancakes, dumplings, biscuits, pies, and crullers constituted Canadian cooking. Without counting, what seem to be American influences outnumber specifically English ones in the list of recipes — Rhode Island, Boston Brown, and corn bread; popovers and Johnnie cake; Washington and pumpkin pie; and so on. Also represented are Melton Mowbray pies, Kentish cake, Bath buns, Yorkshire and Lancashire Parkin, and other "old country" favourites, as well as Canadian cheesecakes, maple syrup pie, pork cake, corn vinegar, and crabapple ketchup.

26 This is not to imply that Canadian cuisine is merely the product of a happy mid-Atlantic marriage. It is never that simple; and neither American nor English cookery can be considered a "pure" form which had not already heavily influenced the other.

27 In contrast to the Five Roses volume, some of whose recipes are merely lists of ingredients with no mixing or baking directions, Pattinson's Canadian Cookbook is much more scientific and detailed in every respect, including the information that various dishes listed had no food value. It is a closely printed tome which must have daunted some of the trainees. The type of recipe, with ingredients listed above and exact, standard measurement, in cups and tablespoons, minutes, and degrees, was promoted by the Boston Cooking School in the 1880s and 1890s.

28 The use of different measuring systems in Britain and Canada is acknowledged by Ella Sykes in A Home-Help in Canada, published in 1915. She wrote "I learnt...the excellent Canadian method of measuring flour, sugar, butter &c. by the cup, and small quantities by the table and tea spoon. I never saw weighing scales throughout my tour, but at first found it difficult to translate the pounds and ounces of my English recipes". The trainees experienced difficulties too. A complaint registered in Canada against them was that "they use the weights and measures system...a nuisance and not known in Canada homes."32

29 Miss Burnham, supervisor of the Department of Immigration's Women's Bureau, wanted to have compiled a cheap edition "for the girls" combining Mrs. Beeton and the Canadian Cookbook. Her reasoning was that "cooks from England have always a wonderful training in soups, meats, and puddings, of course we excel on this continent in salads, cakes, ices, etc. so perhaps the book could be a combination and give recipes for the cooking of vegetables which are peculiar to this country." (She did not list the latter.) "Canadian ways" in cooking identified by Mrs. Charlesworth involved the preparation of canned goods and the making of salads. The latter were "a very important part of the diet in Canada."33

30 Not for every Canadian, according to tales which had reached the horrified ears of Dr. MacMurchy. She wrote in How We Cook in Canada of "the terrible monotony of the meals in some of our homes. No vegetables served in August but canned peas! No oatmeal or any other cereal for breakfast! Only potatoes, meat and pickles and possibly pie, at every meal! Isn't it sad? and isn't it a sin?"34

31 It is difficult to come up with valid limited comparative generalizations concerning Canadian and British diet of a given period and social class as on the Canadian side there is a lack of the solid scholarly research on a level with that offered by John Burnett's Plenty and Want, Barker, McKenzie, and Yudkin's Our Changing Fare, and more recently, James Johnston's A Hundred Years Eating, and Oddy and Miller's The Making of the Modern British Diet.35

32 Mrs. Charlesworth identified but did not describe other "Canadian ways" and equipment. She recommended that trainees at Newcastle receive special instructions on the care of hardwood floors and on the disposal of garbage and care of the refrigerator.36 She wanted all trainees to know how to use the "electric iron, washer and sweeper." Her recommendation of a Bissell sweeper for Cardiff was rebuffed by an Ottawa official because the ordinary type of carpet sweeper was not worth "bothering about."37

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 1233 Six years before, Miss Burnham had considered training in "the use of our electric stoves and vacuum cleaners and in our arrangements re milk and ice" as essentials in a one-week course in Canadian methods of housekeeping to be given to English domestics at Canadian hostels.38

34 So-called labour-saving devices in the household — and their general availability in Canada — has been used as an inducement for people to come to this country, at least since 1907 when a pamphlet, Canada Wants Domestic Servants, was published. This is also evident in a 1924 memo from the London Office of the Department of Immigration:

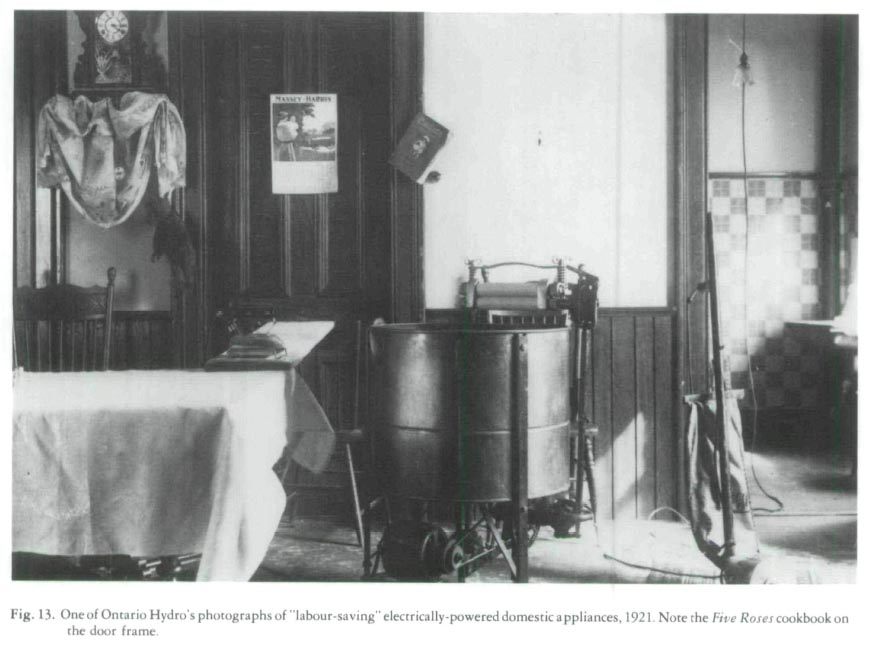

Among several pictures that Ontario Hydro sent the Department to help recruit new Canadians is figure 13. Never mind all that business about yearning to breathe free. Yearning for washing machines and vacuum cleaners is more like it!

35 Still, not everyone thought that Canadians had all the latest things in the labour-saving line — whose appeal, at the time, is reminiscent of present fascination with and faith in home computers as revolutionary agents of change. As Alice Ravenhill, a home economics specialist, wrote in her memoirs reflecting on her arrival in Canada from England in 1910:

Such labour-saving devices, however, may have served to raise standards of household cleanliness and work41 more than they allowed women to sit or lie around dreaming up notions of equality and independence. As far as middle-and upper-class women were concerned, at least, it was not a particularly liberating experience to have to do themselves with a machine domestic work that previously had been the province of domestic servants.

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 1336 Further, it should not be supposed that some of these machines did not still necessitate an immense amount of manual labour. Ella Sykes describes wash day with a non-automatic machine on a prairie farm:

37 What these machines and their electric (and later automatic) successors accomplished eventually, as American historian Susan Strasser demonstrates, was to put out of business small commercial laundries and washerwomen who came in by the day.43 While this conclusion should not be transferred uncritically to Canada, it raises questions and undermines some loose assumptions relevant to the Canadian experience.

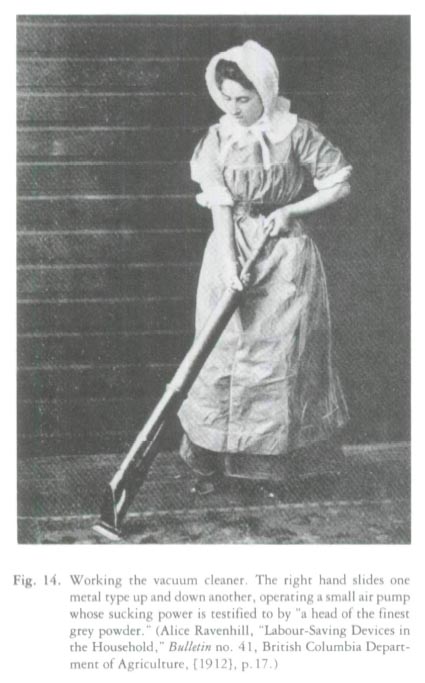

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 1438 The training hostel evidence does not address the issue one way or another. The only reference comparing laundry work in Canada and Britain was Mrs. Charlesworth's: "I find that the girls are given special instruction in the starching and ironing of old fashioned stiff collars and shirt fronts, which I consider unnecessary, in as much as they will never be asked to do such work in Canada."44

39 Should we conclude that the "Old Country" was behind the times, wedded to stuffy traditions, anachronistic stoves, fashions, and methods of housework? Of course this would be a gross oversimplification. The training schools were not Britain in microcosm, and Mrs. Charles-Worth did not know it all. She came, however, to subscribe to that thesis, concluding that the system of training "is not likely to fit the girls for domestic work in Canada, while it may fit them for work in Great Britain. The system of work in Canada and Great Britain varies so much that what might be considered highly efficient in Great Britain would be only second class as far as Canada is concerned.45" Some Canadian employers agreed. The Department's analysis of graduates who failed to give satisfaction in Canada was that they had not grasped "the routine of household work as the Canadian housewife knows it...stressing the value of time in minutes rather than hours." 46

40 The influence of scientific housekeeping and "Taylorism" with its time-motion studies and emphasis on planning is clear in the statement. Was this more successfully promoted in Canada than in Great Britain, and if so, why? Another factor contributing to the different systems might have been the greater proportion of specialists who formed the domestic retinue of propertied Britons, as opposed to the Canadian general servant required to accomplish a great variety of tasks in a day.

41 As Mrs. Charlesworth suggested, the training schools cannot be seen to have been a conspicuous success. While the Department received one letter from a thrilled employer,47 others wrote wondering what had been taught. Summarizing a series of interviews, some with happily settled graduates, the Department concluded, "Even these trainees felt that although their training benefitted them, they did not have any idea of the way our kitchen work was done nor the real type of cooking the householder expected." 48

42 Though "Canadian ways" were not and cannot be seen to have been successfully conveyed by the training hostels and the historical evidence left in their wake, at least they provide concrete cross-cultural comparisons in the sphere of domestic work, and refute assumptions that Ontario (or at least Toronto) was British in every respect save geography and weather before American television and franchise food. It is easier for museum curators and historians to assume that the material culture and domestic life of (English) Canada, Great Britain, and the (northeast) United States were identical. But this obscures the rich varieties of experience and possessions of earlier Canadians.

43 An investigation of "Canadian ways" does not need to be limited to the sources consulted for this paper. Several lines of investigation were considered, though not attempted. One might compare and contrast the contents of runs of domestic magazines published, say, in London and Toronto, or compare the contents of published household manuals or home economics courses in the two countries. To balance prescriptions and theoretical models of this type, one might examine illustrations and photographs of domestic life here and there. (Of course, these need to be approached with one's critical faculties intact. Like any other historical document, they can mislead, distort, and romanticize, and do not offer the universal truths sought.) It might be worthwhile, as well, to compare and contrast, in Britain and Canada, domestic consumption patterns, commercial foods, work and meal schedules, the cost of living, household account books, personal inventories, trade catalogues, patent records, industrial designs, and other specific household appliances and artifacts.

44 To make any sense of these comparisons, it needs to be determined how our neighbours to the south fit into the whole scheme. Might a move across the ocean or over a border be less drastic, in domestic and material terms, than a move from rural to urban area or from one class to another?49 What were some of the major differences between and the influences on women's work in the home in the three countries? Then, try the real question — why?