Reviews / Comptes rendus

Glenbow Museum, "The Great CPR Exposition"

Bill McKee and Georgeen Klassen, Trail of Iron: The CPR and the Birth Of the West, 1880-1930 (Vancouver: Glenbow-Alberta Institute in association with Douglas & McIntyre, 1983). $29.95.

"The CPR West Conference," Glenbow Museum 21-25 September 1983. Conference papers to appear in June 1984.

1 There is much to admire and, depending upon your perspective, much to question following a visit to the "Great CPR Exposition" and an examination of the associated book The Trail Of Iron. In addition a major conference "The CPR West," took place at the Glenbow Museum and Archives. In total the three events, exhibit, book, and conference, represent a formidable amount of work on the part of Glenbow staff. All three events were of the blockbuster variety so favoured these days by ambitious museum directors and boards of trustees. There is something in this effort for everyone. Conversely almost everyone will wish that more had been provided in specific areas of personal interest.

2 The "Exposition", which is the major focus of this review, occupies approximately 8500 square feet of gallery space. The viewing route is essentially circular around an elevated central portion of the gallery which has been effectively used to display large dioramas and models depicting aspects of the CPR's construction along with re-creations of a "typical" railway station and sections of CPR dining and sleeping cars. There is a pleasant sense of space throughout, and the use of colour and lighting gives the exhibit an inviting feel. Photographs run through all portions of the exhibit like a rich vein of ore, supplemented lure and there by pockets of colourful art and scale models. Documents and artifacts are found in lesser profusion in an accurate reflection of the limitations of museum collections related to the CPR.

3 The exposition and the book were intended to focus attention on the CPR's impact on the west and the "political and economic reality" of the railway which "bound the nation together," arriving on the way in Calgary in August 1883. The exhibit attempts to fulfil these ambitious objectives by dissecting the subject into fifteen topical themes of varying sizes and effectiveness. Construction is explored from overlapping perspectives so that five areas deal in all or part with the subject. Other areas include the impact of the CPR, found in two areas, great men of the CPR, found in three, and single areas dealing with each of ships, hotels passenger service, and a typical railway station from the 1920s. "Images Along the Line" serves as a concluding statement.

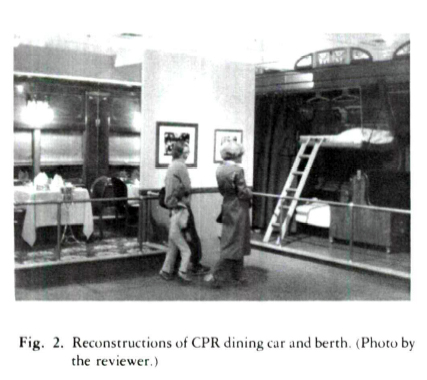

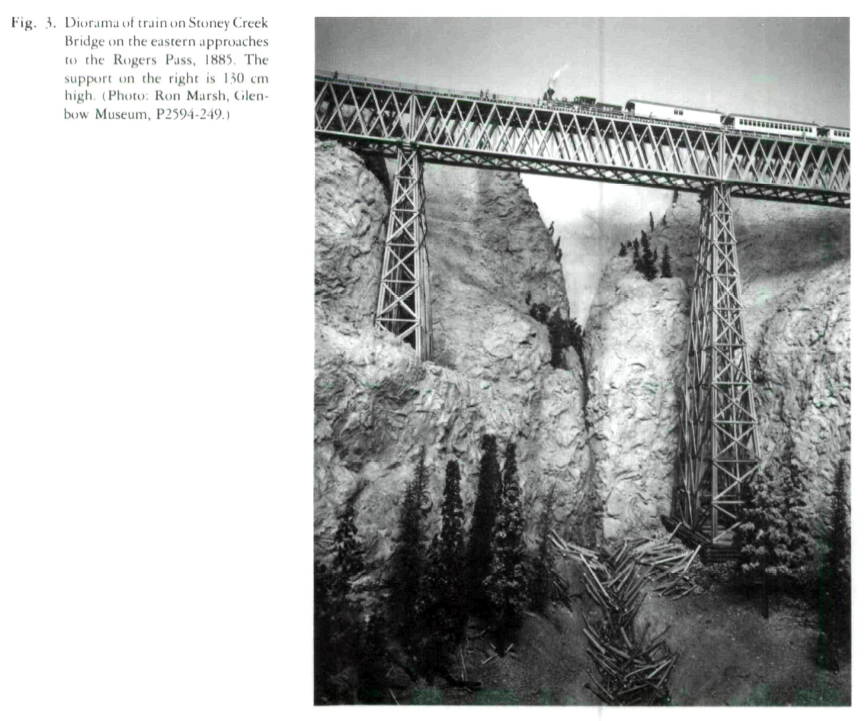

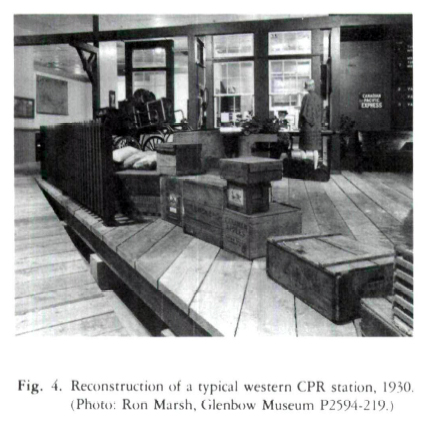

4 In overview the exhibit has many of the flaws and weaknesses which mark much of the corporate and business history that has been attempted in Canada. Management achievements are overemphasized, while at the same time no insight is gained into how the business was run or decisions and policy made. A sort of chronology of positive events in the company's western history is provided, but western problems, other than mountain snows, are virtually ignored. Artifacts illustrating the themes, except for several very effective recreations, tend to be predominately memorabilia. The photographs on the other hand are superb in range of subject matter and quality of image and could have stood alone as an exhibit. The art is arresting but is much narrower in subject matter and time.

5 Some of the specific problems with the exposition which I noted but which might be of less importance to someone with different interests included the following. There is a curious reluctance to include anything of a political nature in the labels. Statements such as, "The nation's first government, which had endorsed the railway, was rocked by scandal and replaced by a more conservative government," and "Mackenzie's conservative form of government was no longer what the public demanded," could be quite misleading to one unfamiliar with Canadian political history of the 1870s. There is no explanation of the crucial abandonment of the northern route for the southern route through Calgary. Railways are the only element of the "national policy" mentioned. The contract system of construction is not explained, and there is no sense of the scale of construction in terms of manpower and materials. The prairie construction model, for example, suggests that a few men could have done everything. There are many locomotive models but no cats, there are no uniforms of train crews or hotel staff, and the function of construction camp artifacts is not explained. The CPR Telegraph Service is given a single sentence in the exhibit and no attempt is made to explain the role of telegraphy in the operation of a railway, or that the CPR telegraph was the first transcontinental line in Canada. In total I wished that more attention had been paid to railway business and less to Van Horne's private art collection and images along the line.

6 There is little humour in this staid exhibit other than an intriguing collection of cartoons drawn by Van Horne for a young relative in which he depicts himself as an elephant smoking a cigar. An unintentional note of amusement is caused by locating an album of train wreck photographs in the reconstructed railway waiting room One well-known western Canadian historian suggested that this might have been the beginning of the CPR's effort to diminish its passenger service! There are cartoons and stories told by western farmers at the expense of the CPR which could have been included to correct the one-sided image presented and add another dimension to the otherwise serious labels.

7 Among the highlights of the exhibit for me was the opportunity to compare the work of the numerous photographers who recorded aspects of the CPR often for the use of the company itself. The photographs of W.J. Oliver found in the "Industries" section were among those which I found new and interesting. Anyone wishing to have a good introduction to this rich source of documentation should certainly examine a copy of the largely photographic Trail of Iron by McKee and Klassen. Other highlights from the exhibit include the model of the Stoney Creek Bridge which stopped every visitor who came by because of its detail and overall impression. Many visitors will find the three quarter-size recreation of a mountain snow shed to be impressive, although personally I did not feel that the result justified the great effort required to work with the large timbers. Finally the typical station complete with telegrapher, along with the following dining- and sleeping-car sections are memorable. If one is interested in memorabilia there is much to examine, ranging from the last spikes, to Crowfoot's CPR pass and W. Van Horne's large vest, to hotel furniture and silver, and a cheque for a staggering sum of money. The memorabilia presented is a good cross section of the types of things people save while more utilitarian objects were worn out or discarded. In this respect the photographs, treated as artifacts, serve for much of the material history ot the CPR that is missing and may never be recovered.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 In contrast to the effective use of photographs and fun facts the omissions in the history of the CPR in the West and the choices of themes to emphasize appears less satisfying. The exhibit presents the positive and the pleasant in the history of the CPR in the west and ignores much that is controversial and potentially unpleasant. Urban historians will find the treatment of the CPR's impact on western urban growth superficial and unsatisfactory and this includes Calgary. Labour historians will take issue with the virtual exclusion of the worker from this exposition. There are no unions, there is no labour unrest, and no sense of the contributions of tens of thousands of men and women who over a century kept the CPR's diverse interests operating. There are railway engines but no firemen, passenger cars but no porters, and track sections but few repairmen. There is no political dimension to the exhibit. The railway is conceived but neither the Conservative nor the Liberal parties are ever mentioned. There are no election issues, no farmer protest groups, no third parties fighting for a better deal on discriminatory western freight rates, and no provincial governments unhappy about the CPR's policy of slow branch line development. Business historians will find great leaders in bronze and marble busts but will not find a sense of how a great corporation operated, made policy decisions, or implemented programs in the fields.

9 At this point as Glenbow staff sit poised with pen in hand to reply to these presumptuous comments I must point out that many of the criticisms listed above were in fact dealt with at the September 1983 "CPR West Conference" and that these papers are to be published in 1984 (too late to serve as a resource for the exposition). Trail of Iron also makes reference to some of the issues which I have raised. Glenbow's director, Duncan Cameron, in a spirited reply to a Globe and Mail critic in August indicated that the "Exposition" should not be viewed separately from the book and presumably the conference as well. Perhaps, but excellent as it was, the conference involved fewer than two hundred people, while Trail of Iron sells for $29.95, a weighty price for all but the most ardent railway or photograph buff. When the average visitor, if there is such a creature, tours the present exhibit or will tour a scaled down travelling version in 1984, the historical balance will still not be obvious.

10 The "Great CPR Exposition" leaves the visitor with a series of pleasant impressions of CPR hotels, mountain scenery, and a nostalgic view of railway stations, trams in general, and passenger travel in the good old days. The visitor will not leave the exhibit with an appreciation of the impact on the CPR on the west in all its dimensions nor will there be an appreciation of the "reality" of the railway that bound the nation together. One will gain an enhanced sense of the multiplicity of the CPR as an entity in the west and perhaps an inkling of what the CPR first meant to the west. Even if the final impression is less than the Glenbow staff might have hoped for, they deserve full credit for a terrific effort aimed at a number of publics. In my view, the 'exposition" suffered as a result of this dispersion of effort but any multi-faceted approach to a subject is bound to produce unequal results. This exhibit is professional, polished, and polite. It could profitably stand an infusion of some of the interpretative content from the conference papers and a touch of coal-dust, sweat, and boiler heat. I still, however, would not have wanted to miss it, and when it hits the "road" or "tracks" it will be well worth a visit.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4Objectives of the Exhibition

11 The idea of creating an exhibition at Glenbow on the history of the Canadian Pacific Railway in western Canada first was raised in early 1981. Impressed by the public lecture series being offered by other departments of the museum, the archives proposed that it offer in 1983 a similar program on "the arrival and impact of the CPR in western Canada up to 1920's," to mark the centennial of the railway's arrival in Calgary. In subsequent months a team, composed of representatives from most departments, developed a much larger CPR program consisting of a major exhibition, a travelling version of the show, an accompanying book, a conference and an associated publication, as well as a related education program and museum shop sales. Largely owing to the initiative of Tim Rogers, president of the Canadian Folk Music Society and associate curator of music in the museum, a Sunday afternoon concert and album of Canadian railway folk music were also added to the plans.

12 We quickly decided that the CPR program would be aimed at as wide an audience as possible. The central feature, the exhibition, was intended to educate and entertain a broad spectrum of visitors. Even its title, "The Great CPR Exposition," was designed to convey to the public the popular tone and big scale of the exhibition. The accompanying book, Trail of Iron, was also directed at the same wide audience. Composed of a limited text, approximately 150 carefully selected historical photographs, and two colour sections illustrating CPR advertising and works of art inspired by the railway, the book was intended primarily as a visual statement of the story-line conveyed in the exhibition. It examines the arrival and impact of the railway in slightly greater depth than was possible in the exhibition, for those who wish to explore the subject somewhat further. Of course, it was also planned as a more permanent memento of "The Great CPR Exposition" for the public and designed to survive in the marketplace, after the exhibition had closed, long enough to recover the investment.

13 The CPR West Conference, hosted by the museum between 21 and 25 September 1983, was organized for those members of the public who wanted to explore in ever greater depth several of the most important elements of the complex relationship between the CPR and the west up to 1930. Twenty speakers from across Canada were convened to review topics as diverse as the CPR and Indians, the CPR and tourism, the CPR and films, and the CPR and the western Canadian petroleum industry. The museum, in conjunction with Douglas and McIntyre, will subsequently publish a selection of the conference papers to ensure that a permanent record is available.

14 In designing the exhibition, we used a number of tools to reach the public. We have mentioned that the title itself was designed to convey the popular nature of the show. Faced with an extensive storyline text because of the complexity of the topic, we adopted the "newspaper headline" design for the text panels introducing each section of the exhibition. These enable visitors to select the extent of text and depth of story they prefer to read.

15 Aware that the size of the exhibit and the complexity of the story-line could fatigue visitors, we endeavoured to use a wide range of media to alter the appearance and mood of the show from gallery to gallery Nevertheless, for those who tired or wished to pause and reflect, old oak waiting room benches from the Winnipeg CPR station were placed at strategic points.

16 Because of their potential for recreating several dramatic features of the history of the CPR within the limited space available for the exhibition, and because of their wide appeal, we soon decided to include model dioramas at several locations in the galleries. A group of volunteer model railroaders agreed to build three miniature (O-scale) dioramas illustrating key scenes: a typical end-of-track scene on the Prairies in 1882 or 1883; the Stoney Creek Bridge on the main line east of Rogers Pass in 1886, as regular passenger service commenced; and Calgary in August 1883 as the CPR arrived. These three scenes, compressed to fit the available gallery space, were assembled with careful attention to detail, the modellers repeatedly consulting archival photographs, the written record, and seeking advice from Canadian Pacific archivist, Omer Lavallée, and other authorities. The first two dioramas seek to convey the visitor, in imagination, to the scene of construction and dramatic bridge building. The Calgary scene illustrates the humble beginnings of the community, and hence the powerful impact of the railway on all towns and cities along its western main line and branches.

17 A fourth diorama, borrowed from the Burnaby Art Gallery, provides viewers with a compressed interpretation of the main line between Vancouver and Cochrane, Alberta. Intended to illustrate some of the operational problems encountered by the CPR, it has an operating N-scale passenger train which passes through the spiral tunnels. This operating layout, along with an adjacent explanatory panel, map, and plan of the tunnels, has proven particularly attractive to visitors, who spend much time studying the train's passage. Needless to say, many visitors, particularly children, find this a high point of the show. The impact of this gallery is further enhanced by the presence of volunteers who operate the model and answer what questions they can; some of the volunteers in this section are retired locomotive engineers who regularly worked the spiral tunnels and tell visitors of their experiences. One gentleman was even heard singing railway songs to the visitors.

18 Distributed elsewhere throughout the show are fine live steam, O-scale, and HO-scale models of locomotives, rolling stock, and standard buildings, such as stations and water towers, which illustrate the evolving and complex nature of the company's operations. The diversity of scale was determined by the availability of quality models as well as our desire to provide the visitor with differing visual experiences.

19 Several full-scale or almost-full-scale dioramas were also incorporated into the show to help provide visitors with as life-like an experience of the railway as possible. As they enter the section of the exhibition which deals with railway operations and the improvements such as stronger bridges that were gradually introduced (topics that could be dry and boring to many people), visitors pass through one end of a three-quarter-scale snow shed which reaches to the ceiling. Thirty feet away, along the standard gauge track (laid by an actual CPR crew), is a section gang and hand car. Since it was not possible to place a real locomotive in our second floor gallery space, we believe the snow shed scene provides some of our visitors with the impact of a full-size railway scene. In other galleries, using CPR standard plans, we have constructed a station. Visitors can wander through the waiting room, sit on a bench, and look into the office, where many of the features of a 1930 station are shown. The atmosphere is enhanced by the sight and sound of operating station clocks, the sounds of trains approaching, stopping, and passing the station, and the periodic punctuated clacking of actual telegraph messages arriving in the office. In the adjacent final gallery, which examines the CPR's key role in the western Canadian tourist industry, full-scale sections of the interiors of a 1914 sleeping car and 1929 dining car from the Trans Canada Limited give a real sense of what earlier train travel was like. Assembled through generous loans from a local collector, the superb railway museum in Cranbrook, B.C., Canadian Pacific, and Glenbow's own collections, these two components of the show are especially popular with those who remember travelling by rail before 1930.

20 We also found original three-dimensional artifacts useful in describing this complex story. Survey and railway construction tools, as well as remnants from a CPR construction camp, add to the visitor experience. Being in the presence of an artifact that has actually "been there" helps bring the story alive for many people. Other artifacts, such as the contents of the station agent's office — from the shirt, pants, and vest as well as arm bands on the station agent to the multitude of early CPR forms and manuals, typical furnishings, and assorted office clutter — all lend an air of reality to the scene.

21 Other artifacts, such as selections of standard CPR crockery and flatware as well as representative early furniture from the Banff Springs Hotel and Château Lake Louise, were carefully chosen to introduce or remind visitors of several aspects of the railway's diverse operations. Finally, a few artifacts were selected because of their sheer drama to western Canadians. The railway pass issued to the Blackfoot leader Crowfoot, on loan from the National Museum of Man, was highlighted since it symbolizes the general rule of law and order which prevailed among the Indians (with the significant exception of the Riel Rebellion) as the CPR was established in the west.

22 The "Last Spike" and several associated artifacts were placed in the show as symbols of the achievement of the transcontinental line and with it the de facto establishment of a Canada from sea to sea. Because of their symbolism to Canadians, and to heighten their effect on visitors, they have been placed in a framed case in front of a mural showing the last spike ceremony. To reinforce the significance of this treasure, the exhibition was opened by the present Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, a descendant of Donald A. Smith, who drove the last spike in 1885.

23 As archivists, the co-curators were determined that archival material would also play a central, stimulating role in the show. We incorporated approximately 150 reproductions of historical photographs from collections across Canada, as well as numerous original manuscripts, plans, and posters. Reproductions of photographs were obtained to ensure standardized size and quality, but original manuscripts were used, where possible, because of the obvious preference of most visitors. To ensure that they not only helped to tell our story-line but contributed to the mood of the exhibition, most of the two-dimensional items were placed in custom-made reproductions of the wooden frames many Canadians associate with photographs and posters in CPR stations and offices. In addition, albums of reproductions of historical photographs and other documents illustrating several key topics were placed on benches and wall stands throughout the exhibition, for those visitors who chose to relax and peruse them. Finally, three silent films, produced for the CPR to advertise the west, were included in a section of the show that demonstrates the sophisticated promotional campaigns undertaken by the railway company and the federal government to encourage western settlement. The films are considered another optional feature of the show for visitors; they can pause and watch, or they can glance at them and consider them simply part of the immigration gallery atmosphere.

24 For a number of reasons, works of art play a surprisingly strong role in this history show. In several locations, oil or pastel portraits, as well as busts, convey a strong image of the key figures who shaped the course of the company during its first 50 years. We also included representative examples of the artwork of William C. Van Horne, the general manager during construction and the CPR's second president. These paintings, including the album of reproductions of approximately 30 small water-colours he painted for his grandson (in which Sir William appears as a cigar-smoking elephant), were included in the show to illustrate that Van Horne and his peers were many-dimensional human beings.

25 Other artwork, such as architectural renderings and portraits of ships, were included to provide colour, varying texture, and information to the story. Finally, near the end and along the exterior wall of the show, we have provided a selection of the images of the Canadian west which were created by some of the photographers and painters who travelled to the region during the early decades of the CPR. Some visitors will simply enjoy and perhaps recognize some of the mountain scenery; others may see the pivotal role these people played in shaping our image of Canada as a land of imposing wilderness.

26 Our objective was that the blend of these media would provide visitors with a stimulating experience, ranging from nostalgia to education, about the immense role of Canadian Pacific in the west. Responding to our design, one reviewer has described the show as a "feast of sensations."

27 Finally, although we set out to appeal to a wide audience, we acquired a new objective as planning for the show proceeded. After approaching one group of modellers to build our dioramas, we realised that one way of reaching more of the public was to involve as many volunteers in the construction and operation of the exhibition as possible. Subsequently, groups of volunteers were identified who built the snow shed, manufactured trees for the model dioramas and located and installed period telegraph and telephone equipment. A retired telegraph operator provided the telegraph expertise for the messages that are heard in the station office. Since the exhibition opened, a group of over sixty people have given their time to operate the spiral tunnel layout and answer questions from the public, providing a human element to the show.

28 While the exhibition remains at Glenbow we are endeavouring to monitor public response to it. We have installed a visitor's book where the public are encouraged to summarize their impressions of the exhibition and, perhaps of greater value, visit the galleries regularly to witness visitors' reactions to the exhibition.

Georgeen Klassen

Bill McKee