Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Inventory of Ontario Cabinet Makers, 1840 — ca. 1900:

Work in Progress*

Introduction

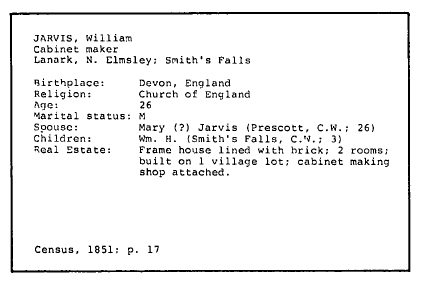

1 This project was initiated in 1981 by the History Division of the National Museum of Man and has been sponsored jointly by that department and the Career-Oriented Student Employment Program, Employment and Immigration Canada, for three successive summers. The project was originally conceived as complementary to the History Division's collection of Ontario-made furniture. Its objectives may be summarized as follows: through an examination of census reports, newspapers, business directories and other archival sources, to gather information on those working in the furniture-making industry in Ontario during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Sources and Methodology

2 Information, primarily from the manuscript census returns, has been recorded on craftsmen involved in the following occupations or businesses: cabinetmakers, joiners, turners, decorators, chairmakers, furniture and chair factories, planing mills, sash and door factories, piano and organ makers, and undertakers. Information on carpenters was not recorded beyond the first year of the project although carpenters' names and the relevant census and page references have been maintained in the form of alphabetized lists in case it later appears that such craftsmen were heavily involved in the production of furniture. To date, it appears that this was not the case.

3 Information has been gathered on a county-by-county basis. Within each county, the primary source material was examined for names of individuals working in the occupations noted above. All available information on such an individual was recorded in a pre-arranged format. To date the following counties have been scrutinized: Carleton, Durham, Elgin, Essex, Grenville, Grey, Haldimand, Halton, Hastings, Lanark, Leeds, Middlesex, Northumberland, Ontario, Oxford, Peel, Peterborough, Prince Edward, Waterloo, Wentworth and York, representing approximately one-half the provincial total. The manuscript censuses, assessment rolls, business directories and newspapers were the primary sources utilized, but certain secondary material was also consulted.

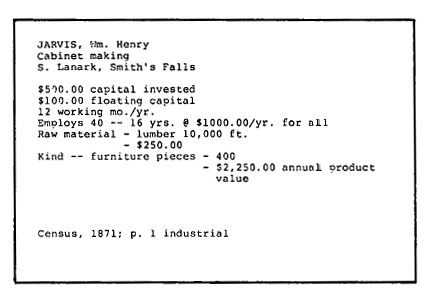

4 Manuscript censuses for the years 1848, 1851, 1861, 1871, and 1881 provided the greatest amount of information about each craftsman, including the subject's name, occupation, location, age, religion, birthplace and nationality. The same facts are also listed for each family member. But the censuses, specifically that of 1871 which includes more complete information on industrial enterprises, also provide insights into the economic health of the subject by describing the residential dwelling and detailing the industrial establishment. Where relevant the 1871 census also lists the number of employees, their aggregate annual wages, and the type and value of both raw materials and products. Nevertheless, there are problems associated with using the censuses: only the 1871 census has an industrial return; the 1881 census has been poorly microfilmed; some censuses are incomplete, missing entire townships or villages; and some are illegible because of the enumerator's poor handwriting and spelling.

5 Assessment rolls were the other major source used. They list the head of the household by name, his or her occupation, location, religion, age, and whether he or she is a freeholder or householder. Assessment rolls also note the number of people in the family and the value of the property being assessed. For information on cabinetmakers, assessment rolls were particularly valuable because they give precise locations including concession or street number while the censuses are broken down only by township or village. Illegibility is again an obstacle, but a greater hindrance is the sporadic nature of the rolls which — except for major urban areas — rarely continue year after year. Furthermore, assessment rolls have a tendency to miss part of the county.

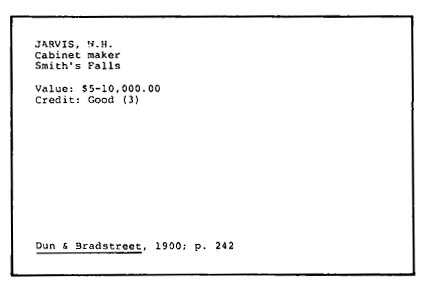

6 One source which poses no problems of legibility are the printed national, provincial and local directories; however, they only list a subject's name, occupation, and location. This source compensates for the small quantity of information provided by including exact locations, and by being so numerous that cabinetmakers can be enumerated every three years for the entire period under study. The Dun and Bradstreet national directory, published yearly from 1864, provides information beyond that of most directories. The true value of this directory lies in its listing of the subject's pecuniary strength and credit rating. Although the Dun and Bradstreet directory does not publish advertisements, most other directories do. Such a advertisement usually makes known the cabinetmaker's name and location, the type of furniture offered for sale, and the price. Some directories also contain local histories which proved particularly useful in the preparation of the county histories which students provided along with the statistical data gathered.

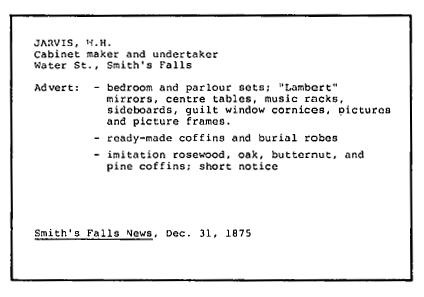

7 Newspapers may also provide local histories, and occasionally articles on local cabinetmakers are found. But for the most part, newspapers were searched for the cabinet-makers' advertisements they might contain. These advertisements may include similar facts to those gleaned from the directories mentioned above. But they may also announce sales, the establishment of a business, and the evolution and dissolution of partnerships. Despite the long period covered by newspapers and the generally excellent selection of papers available, it seems that relatively few cabinetmakers actually paid for newspaper advertising. It appears that only the better established businesses regularly used this form of advertising; smaller businesses advertised only when they had an important announcement to make.

8 Information from these sources was recorded on index cards, one card per cabinetmaker per source. The resulting cards are organized by county and township and, within each township, alphabetically by surname. By surveying all the cards relating to a given cabinetmaker, it is often possible to compose an outline of that individual's career. John N. Gilbert, a cabinetmaker from the town of Picton in Prince Edward county, serves as a case in point. Gilbert settled in Picton in 1838. In 1860 he bought a cabinetmaking shop from James Gillespie who had been cabinet and chairmaker in the town since 1848.1 In 1863 Gilbert and his father, Reuben, formed a partnership which lasted until Reuben's death in 1871.2 During the life of the partnership, the two Gilberts were involved in the cabinetmaking, furniture-dealing and undertaking businesses; they produced products from chairs to caskets made out of walnut, ash, butterwood, cherry, and basswood.3 After his father's death, John went into partnership with Gilbert Lighthall. The partnership was a successful one which lasted until 1900 and reached a pecuniary strength of S5000 and a fair credit rating.4 In fact, their business prospered to such an extent that the two partners had a factory shop in one part of town and a showroom elsewhere.5 In 1886 Obediah Hubbs was allowed to enter the partnership, but he left shortly afterwards.6 When Lighthall retired, John brought his son, N.D. Gilbert, into the company, which became known as the Gilbert Furniture Company; N.D.'s son sold the company in the 1920s.7

Observations

9 Although only approximately half the counties in Ontario have been surveyed and analysis of the data remains to be carried out, enough work has been done to justify several observations. We now know something of the overall shape of the cabinetmaking industry throughout the province. The manner in which the industry changed with time demonstrates that factors affecting the Canadian economy as a whole also influenced significantly the livelihood and production techniques of individual tradesmen. The degree to which cabinet- and furniture-making activities were related to other skills and activities illuminates further our understanding of the nature of the industry. The variety of duties that an individual craftsman could undertake appears to have ranged significantly depending on where and at what point in time he was located. These observations must remain tentative until the information compiled to date is analysed, nevertheless they do point to a promising addition to current knowledge in Canadian history.

10 Probably the most striking feature regarding the overall shape of the industry is the high rate of transiency which appears to have affected the lives of many nineteenth-century craftsmen. In any given area, an average of 60 to 70 per cent of the artisans whose names were noted under occupations related to furniture production in one year were not listed under those occupations in later records searched. It may be that a high rate of geographical mobility accounts for this fact. Or perhaps a change in occupation is reflected in these findings? On the other hand, it was noted that a small number of cabinetmakers remained in one location for long periods of time, and these individuals appear to have profited to the greatest extent from their local activities. Thus while a large number of individuals led a relatively precarious existence, perhaps moving from one town or village to another within short timespans, a few cabinetmakers in each area became established. Once businesses developed beyond a certain critical period, financial security often followed in what appears to have been a process that encouraged increasing degrees of monopolization within local cabinetmaking industries.

11 Most of these activities, especially during the later period, were located in urban rather than rural areas. While most villages inhabited by 200 or more people possessed at least one cabinetmaker during the 1840s and 1850s, increasing centralization of industrial activities suggests that cabinetmakers may have left rural areas in favour of larger centres as the century progressed. The improvement of transportation networks through the building of railways undoubtedly played an important role in this phenomenon, for the location of a cabinetmaking establishment contiguous to a railway station would have improved an entrepreneur's ability to ship his products to centres outside his immediate vicinity. The construction of railways in certain areas of the province to the exclusion of other localities meant not only that many smaller villages and towns died quiet deaths, but also that a large number of one-or two man furniture-building enterprises suffered similar fates. Urbanization meant that businesses had to relocate in the larger centres in order to increase their volume of production and sales and remain financially viable. By the final three decades of the century, in fact, a few businesses in several cities had become so large that each of them employed over 100 workers and were able to dominate the furniture trade throughout entire regions of the province. Thus, for example, the Bennet Furnishing Company and the George Moorhead Company (later known as the London Furniture Manufacturing Company) in London became so large that towards the end of the century their products were being sold across the country and apparently were able to compete on a par with European and American imports.

12 Other factors besides urbanization and the railways were important in determining the shape of the industry. Increasing industrialization caused large-scale production to become more commonplace while at the same time it tended to downgrade the skill level required on the part of individuals producing the furniture. Another factor contributing to the differentiation of labour in factories was the introduction of upholstering during the 1880s and the use of more decorative features on many items of furniture. While changing styles and the exigencies of the fashion world thus shaped in part the nature of the industry, another condition deserving comment was the economic depression of the 1870s which continued until the early 1890s. The listings of cabinetmakers in business directories and the incidence of their newspaper advertisements indicate that many went out of business during this period because fewer consumers could purchase their products. Levels of competition decreased and the average size of remaining firms was larger.

13 One final observation regarding the research completed to date concerns the types of activities in which many nineteenth-century cabinetmakers or furniture-makers became involved. Especially during the first half of the period under investigation, craftsmen who built furniture were also expected to produce coffins and provide funeral services. While cabinetmakers occasionally coupled their furniture-building activities with such pursuits as general carpentry, wood-turning work, and the building of carriages, the most common occupational association was with undertaking. Even by the end of the nineteenth century, the two occupations had not been separated completely. During the 1890s the owner of one of London's large furniture-making firms also owned another big enterprise whose only products were caskets and other products designed for use in funerals.

Conclusion

14 It is hoped that this work can be continued in 1984, and in 1985 if necessary, so that all regions of the province can be thoroughly studied. The History Division expects to publish some of the data recorded as an appendix to a series of catalogues on its collection of Ontario furniture and to make use of other forms of data in conjunction with the exhibition of this collection in new exhibits scheduled to open by 1988. It is also hoped that the data gathered will eventually be entered into a computerized system thus making accessible a broad range of information of use to those involved in the field of material history.

15 For additional information concerning this work, readers may contact the organizer of the project, Christine Grant, Acting Curator of Collections, History Division, National Museum of Man, Ottawa K1A 0M8.

Larry B. Pogue

Appendix

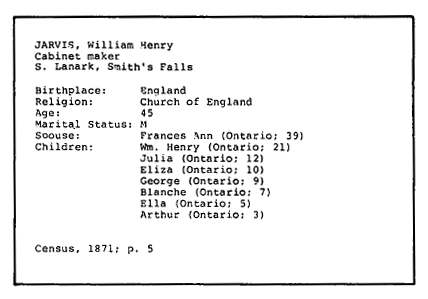

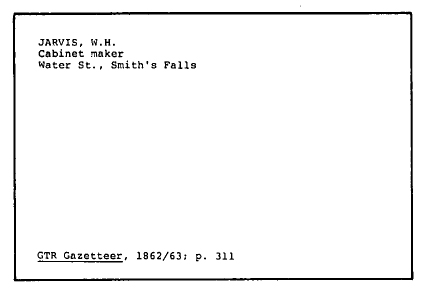

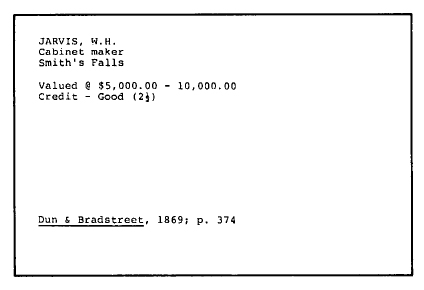

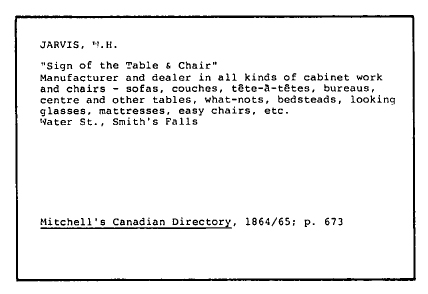

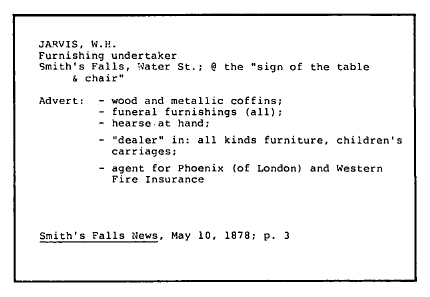

16 Although most individuals whose names are included in the data base are represented by a single card, many craftsmen were located in a variety of sources over an extended period of time. Illustrated are nine of the thirteen cards representing cabinetmaker William H. Jarvis of Smith's Falls, Lanark County. Jarvis's name first appears in the 1851 census. In the examples shown, the last record of his name is that appearing in Dun & Bradstreet in 1900.

* The co-authors of this article have been involved with the project in a research capacity, Luigi Pennacchio in 1982 and Larry Poguein 1981 In addition, from May to September 1983, Pennacchio was employed as supervisor of research and Pogue as senior researcher Other students involved in the project have been Dan Azoulay, Janet Diceman, Nancy Kiefer, Caroline Sibley, Anna-Marie Tarrant, Carolyn Thomson, Jennifer Trant, and Peter Way.