Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

Gravestone Carvers of Early Ontario

1 Dotted across the countryside of southern Ontario, in graveyards established in the nineteenth-century, stand the works of a group of craftsmen about whom little is known. The gravestone carvers of nineteenth century Ontario created memorials which were intended to speak to many generations. Today there is more to consider on these stones than was intended by those who carved and erected them.

2 We began to study early gravestones because of our interest in their carved decorations. We were convinced that many stones were fine works of craftsmanship which should be appreciated and preserved. But we found that little hail been written on gravestone carving in early Ontario. Carol Hanks' work. Early Ontario Gravestones, provides an introduction to gravestones and graveyards, but no one has published a study of the decorative symbols and the men who carved them.1

3 At first we photographed and recorded only those stones which we considered outstanding examples of craftsman-ship. As our research took us to various graveyards, however, we became aware of the vulnerability of the stones. Owing to the materials used for the gravestones and recent atmospheric conditions, the memorials are rapidly deteriorating. Within another generation it may be impossible to decipher the information and appreciate the designs they offer. Because of this, we decided to expand our recording project so that a wide range of carving techniques and decorative detail on gravestones from across the province might be preserved.

4 Since 1978 we have visited a majority of the cemeteries in southern Ontario. Our basic guide to their location has been the 1:50,000 scale maps of the National Topographic System published by the Government of Canada, supplemented by advice from local historical societies and our own occasional discovery of graveyards not marked on maps. We have surveyed each cemetery for the thin slabs of white marble, slate, and sandstone commonly used by early carvers.

5 Our attention has been focused on the decorated area of the stone, with lettering considered only as part of the overall decoration or as an aid to the identification of a carver. We have recorded stones which we considered basic examples of design or technique, as well as those of particular significance, for instance, if the decoration was skilfully cut or imaginatively designed, or the carver's approach was primitive, naive, or totally unskilled, or if the subject matter received some unique treatment. In each case we have photographed the stone and recorded the details of decoration, the name and date of death of the person being commemorated, and any details about the carver. When a particular locality contained examples of interesting styles or works of a carver of distinction, we have attempted to find all examples of the carver's work.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 46 Although the works of nineteenth-century Ontario gravestone carvers do not display the power and originality of New England stones of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many show subtle detail, and some reveal imagination and craftsmanship worthy of recognition. In addition, the subject matter of the carvings and the carvers' techniques and skills in design can provide valuable information about various aspects of nineteenth-century culture. Given the numbers of stones purchased and erected, the carvers clearly provided an important service to their communities.

7 We have recorded stones from the 1790s to the last decades of the nineteenth century but have found that the decorative detail was most imaginative from the 1820s to the early 1870s. Earlier stones seldom have any decoration, and later stones tend to have stereotyped, uninteresting designs. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, decorated stones disappeared completely as marble columns and pillars, and then granite markers, became fashionable.

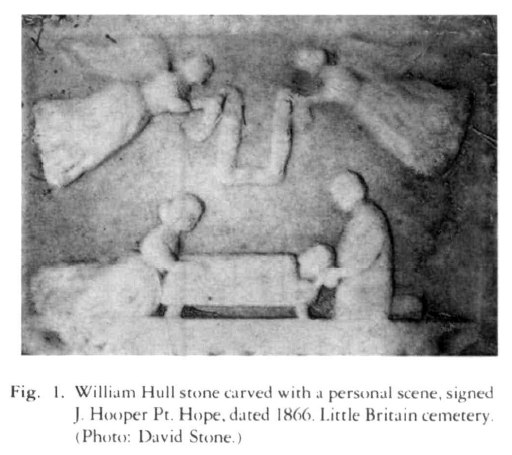

8 Nineteenth-century Ontario carvers were limited in the range of symbols they used: classical decorations such as willows, urns, columns and obelisks, as well as flowers and leaves, hands, lambs, birds, angels, and mourning figures, are the decorative elements of most early Ontario stones. Most stones have combinations of two or three symbols; a few have combinations of many, often with extraordinary results. Occasionally a personal scene was carved (fig. l), or unusual combinations of designs were brought together. Nevertheless, in general there is such consistency in the way the designs were presented and combined that we feel certain that standard pattern books and even templates must have been in common use. We have looked for examples of these in Ontario and England but have not yet found any.

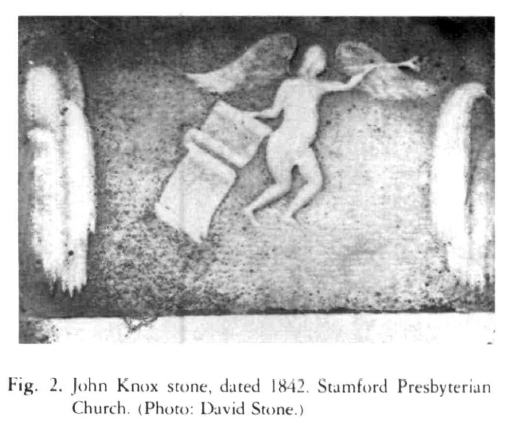

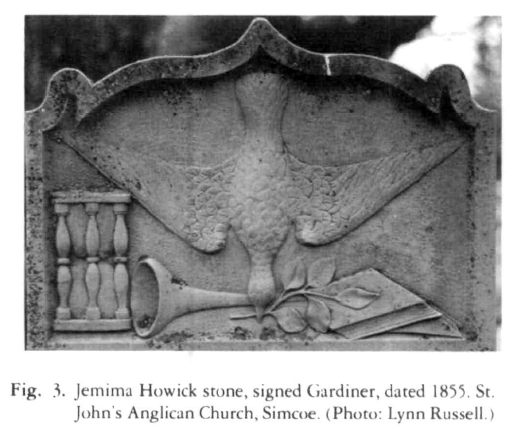

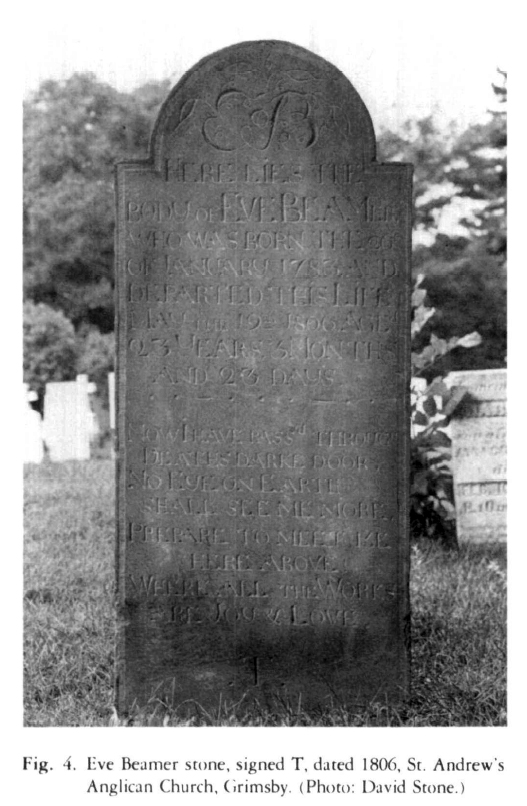

9 The subtle variations and the skill (or lack of skill) with which designs were assembled and cut on the stone give information about the craftsmanship and artistic vision of the carvers. We have seen work that is dull, awkward, over-worked, and even absurd. We have been delighted by the charming simplicity and almost child-like imagination of some carvers (fig. 2). Occasionally we have encountered a carver of considerable skill and sophistication. For instance, the stones signed "Gardiner" in the Simcoe area are elegantly designed and finely cut, and the subject matter is sometimes presented in unusual combinations (fig. 3). In the Niagara area we have found a few stones by a carver who probably worked in the 1820s and 1830s and signed himself only as "T" (fig. 4). He created beautifully lettered stones decorated with simple, delicate flowers.

Display large image of Figure 5

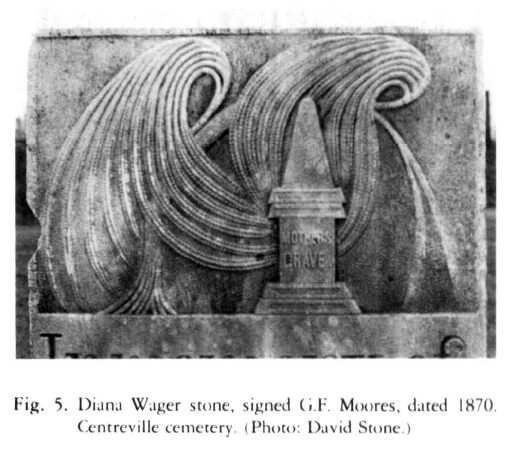

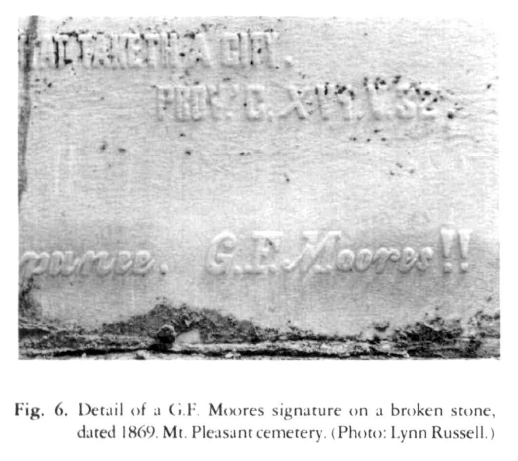

Display large image of Figure 510 More rarely, we have found a carver of originality. Such is Gardiner Moore of Napanee who carved with a unique vision. He created abstract designs of great power, working with the same limited number of symbols used by other Ontario carvers (fig. 5). Moore left few traces behind him except his stones, a suggestion of financial difficulties in one assessment record, and a few indications of either quirky humour or mental instability on the base of some of his later stones (fig. 6). In trying to find details of the life of Moore and other interesting carvers, it has become evident such information will be difficult to locate. Not half the stones we have seen have visible signatures or business locations. Some carvers did advertise in their local directories and newspapers. Those working in the second half of the century appear as marble cutters or manufacturers in the censuses of the time, but local histories do not seem to have singled out these craftsmen as noteworthy.

11 Our photographic survey of the province is nearing completion. We now plan to assemble a catalogue of decorative symbols and their variations and a checklist of Ontario carvers. This catalogue will then provide us with an organized basis from which to work on further topics, especially the study of the work and lives of identifiable carvers who have made important contributions to the craft. From these studies we anticipate that a picture of this craftsman in his society will emerge.

12 We hope that our work will prove useful to researchers studying other aspects of nineteenth-century culture, and we welcome correspondence on any topic that might help other researchers or assist us in our studies.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6