Research Reports / Rapports de recherche

German-Alsatian Iron Gravemakers in Southern Ontario Roman Catholic Cemeteries

1 At least eleven Roman Catholic cemeteries in southern Ontario contain cross-shaped iron gravemarkers created in the Germanic tradition by local blacksmiths. With the exception of a few severely simple structures of iron bar, these forms are enhanced by coiled strap foliage, cast-iron figures, and sheet-work cut-outs of religious motifs. Transforming stone-filled cemeteries into paradise gardens full of Lebensbaume, or Trees of Life, these iron markers symbolize the resurrection of Jesus and the hope of everlasting life.

2 In Waterloo County (Waterloo Region), Germanic iron crosses are found in abundance at St. Agatha's churchyard, St. Boniface's churchyard, Maryhill, St. Clements Cemetery, and, in undetermined number, at St. Joseph's churchyard, Macton (see below). These works were created for South German and Alsatian Roman Catholics who in the 1830s and 1840s settled around the area previously acquired by Swiss-German Mennonites from Pennsylvania. In the 1840s and 1850s some of these settlers moved about 100 kilometres north to Bruce County, where their settlements produced a cluster of six cemeteries at Mildmay, Deemerton, Carlsruhe, Riversdale, Chepstow, and Formosa. The last site, at Immaculate Conception's churchyard, is the richest and most varied of those studied, with Maryhill a close second. One site outside these two areas is the Roman Catholic churchyard at Zurich, Huron County.

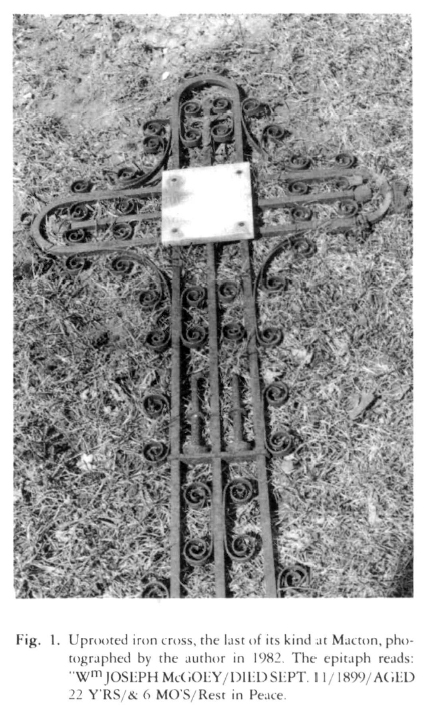

3 The numbers and condition of the crosses vary from place to place. Those at Formosa and Maryhill, perhaps because of their abundance, are in excellent condition, carefully painted and maintained. Riversdale, with only two crosses, contains the smallest deposit in Bruce County, while Macton, which reportedly once had several, contained but one in 1982. This last remnant, while intact and still bearing its crucifix, had been removed from its concrete base and placed against a shed behind the church, presumably when nearby stones had been collected for a concrete-set constellation, as is the practice in some old cemeteries (fig. 1).

Display large image of Figure 1

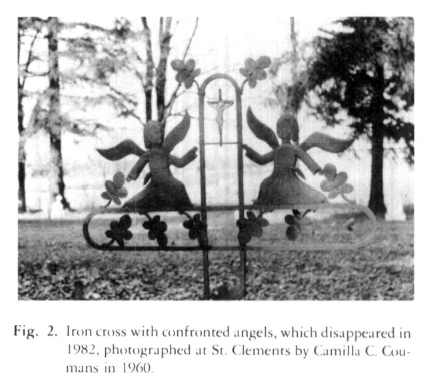

Display large image of Figure 14 Perhaps the most regrettable loss has been the disappearance of one of two very distinctive crosses with confronted cast-iron angels and rose leaves. Although the Maryhill version still stands, that of St. Clements, which in 1981 had lost one of its angels, was missing in 1982. Fortunately, slides were made of this work in 1960 by Camilla C. Coumans, including details of the angel figures, and others were made by the author in 1975 and later (fig. 2). The bold and naive angel crosses reiterated a theme of angels flanking the cross or tree of Life frequently also seen on gravestones in Roman Catholic cemeteries which contain the iron crosses. The losses at Macton and St. Clements suggest the importance of gravemarker research and photographic recording: neither parish priest, gravedigger, nor grounds-keeper at St. Clements Cemetery were aware of their loss when consulted in 1983.

5 Although occasional written notice had been taken of the iron markers of Waterloo and Bruce counties, the first formal study was published by Camilla Coumans in 1962.1 A Chepstow schoolteacher, she prepared several hundred slides (present location unknown), and a selection of duplicates was made by the author. She was able to interview several blacksmiths, the last survivors of those who had made iron crosses. The present writer undertook the iconographical study of these works and in 1975 published a long article in Ontario History.2 In the process, the writer visited and photographed crosses from nine cemeteries in Waterloo and Bruce counties, interviewed relatives of marker-makers, and examined related literature on German prototypes and their iconography. Another rehas published several volumes of local and Canadian Indian history, has used the churchyard at Carlsruhe as a teaching resource and prepared a collection of slides of that site. On-going research has producted further photographs of the sites and visits to Macton and Zurich (made at the suggestion of Michael Bird). The intention is to produce a complete inventory of the surviving crosses and to analyse their symbolism.

6 The structural organization common to the cross, the tree, and the human body — axial symmetry — requires not only a mirror image of left and right, so that each extended arm repeats the terminus of the other, but an assymmetry between foot and head. The upper and lower poles of the vertical axis always terminate in emphatically different forms. In Waterloo County the top is often occupied by a crucifix. Each crossed structure also contains a unique point, the centre, where horizontal and vertical axes meet. This point is frequently occupied (as in the human body) by the image of a heart, symbolizing the centre of human identity, spiritual and emotional being. In other cases a small plate of marble or tin is found in this position, presenting the name and date of the deceased. Other examples have lost their name-plates and display an empty place where, as Yeats wrote, "the centre does not hold."

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 27 The floral and foliate elements enhancing these crosses vary from highly schematic to elaborately naturalistic. That the markers are both trees and crosses is made clear by the placement of the same forms, by the same makers, on the steeples of many of the churches adjoining these cemeteries.

8 Although the late Simon Dentinger, now buried at St. Agatha beneath a cross of his own making and within sight of the steeple cross which he also made, was the last artisan to make an iron gravemarker for any of these sites, this work is not at an end. A tall new iron cross rises proudly where it was erected recently in front of St. Boniface Church in Maryhill to mark its centennial. This was made, appropriately, not by a local blacksmith, but by a local automobile body-shop worker, a German immigrant like those before him. Markers and makers come and go, but traditional images remain.