Articles

The Bottles of Northrop & Lyman, A Canadian Drug Firm

Les fouilles sur les sites de la fin du XIXe siècle au Canada ont souvent livré des flacons de médicaments frappés du nom de la Northrop & Lyman Company. On sait très peu de choses sur cette entreprise, même si l'on peut en déduire la réussite par le nombre de flacons portant sa marque qui se retrouvent dans les collections archéologiques et autres. Elle semble avoir été en activité de 1854 à 1980 environ, comme pharmacie desservant le marché local d'abord, puis comme grande société pharmaceutique réputée sur le plan national et international. Elle fut, à une certaine époque, l'un des plus gros fournisseurs de médicaments brevetés dans le Dominion. La présente étude constitue un premier examen des bouteilles de la Northrop & Lyman; l'histoire de l'entreprise, ses méthodes de commercialisation et la publicité consacrée au produit servent de contexte et de cadre de référence. Il est à espérer que cette étude permettra de reconnaître d'autres contenants, flacons en verre ou en autres matières, de la Northrop & Lyman.

Medicine bottles embossed with the name of the Northrop & Lyman Company are often excavated on late nineteenth-century Canadian sites. Despite the success that can be inferred from the number of marked bottles in archaeological and other collections, little is known of this company. It appears to have been in business from 1854 to about 1980, beginning as a retail drugstore serving a local market and becoming a large pharmaceutical firm with a national and international reputation. The company was at one time one of the biggest dealers in patent medicines in Canada. This study is an initial examination of Northrop & Lyman bottles, with company history, marketing, and product advertising included as background and context for the containers. It is hoped that more Northrop & Lyman containers, glass bottles, and bottles in other materials will be recognized as a result of this research.

Introduction

1 By the early years of the twentieth century, it was clear that Parliament intended to create legislation "regulating the sale and manufacture in Canada of proprietary medicines, and the advertisement thereof."1 The result, Bill 146, ratified as the Proprietary or Patent Medicine (PPM) Act, directed that manufacturers, or Canadian agents acting as manufacturers, be licensed, that secret-formula remedies be registered and ingredients disclosed to the Ministry of Inland Revenue, that substances such as cocaine and alcohol be restricted or removed altogether from patent medicines, and that the presence of other substances be noted clearly on the bottle wrapper.2

2 The need for national patent medicine legislation had been felt for many years, not only in Canada, but in Britain and the United States; an argument advanced in the Senate to hasten passing of the bill was that Canada was "behind the rest of the civilized world on this question of drugs."3 However, the nature of the drug trade in Canada had changed remarkably over a number of years. Writers for the Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal lamented the state that a profession in pharmacy had reached since the days when clerks (apprentices) gained practical experience in pharmacy through attendance at mortar and pestle.4 In 1905, Parliament ordered an investigation of the drug and proprietary medicine trade in Canada, headed by A.E. Du Berger.5 His report, Sessional Paper No. 125, 5-6 Edward 7, 1906, identified the key role played in Canada's drug trade by large pharmaceutical and patent medicine manufacturers and wholesale distributors. A long-practising pharmacist himself, Du Berger found that the pharmacist had to a large extent become merely an intermediary between drug manufacturers and the consumer: "Nowadays, it is very seldom that we can meet with a retailer who himself, manufactures the pharmaceuticals he has to sell his customers."6 Hence, druggists relied on wholesale drug manufacturers, who unfortunately operated in Canada with no other standards for their behaviour than those self-imposed:

3 Du Berger found many examples of bad faith regularly practised by wholesale distributors in supplying raw drugs and preparations to pharmacists. Wholesalers did not always verify the quality and purity of raw drugs imported in bulk and sold in smaller quantities, did not follow an approved formulary, were not obliged to submit their preparations to inspection and often would not admit to being the manufacturer by neglecting to disclose their name on the labels of their preparations. Pharmacists were forced to deal with adulterated raw drugs and medicines, preparations with recognized medical names differing from published authority in strength, quality, or purity, wood alcohol substituted for part or all of the ethyl alcohol called for, and duplications of standard preparations sold under different names. Pharmacists were not always aware of product contents and could not advise customers on proper usage of preparations as they had been trained to do.

4 Of proprietary or secret-formula remedies, that is, patent medicines, Du Berger noted that anyone, no matter his credentials, could make, package, advertise, and market anything as a medicine. He particularly named as dangerous, advertising addressed to the public that exaggerated the seriousness of fairly common symptoms and made false claims about remedies' contents and actions, the presence of substances that become dangerous by accumulation in products intended for constant use, alcoholic content so high that some patent medicines could be substituted for beverages, and the creation of narcotic habits from long-term use of proprietary products.

5 Thus,it was the manufacturing aspect of the drug trade that Parliament sought to regulate. The act affected all manufacturers of medications for internal human use prepared without a doctor's direction for over-the-counter sale, including practicing pharmacists, individual proprietors, and large manufacturing concerns. As this study will show, at the time the act was passed, Northrop & Lyman was operating as a manufacturer and wholesale dealer in patent medicines and other products, many of which the company manufactured itself. The partnership had existed for almost half a century, the business changing in nature as the firm grew in size. Whether Northrop & Lyman dealt with its clients as Du Berger found that others of its type did is not known and has not been investigated in this study. The focus of the present paper has been the identification and dating of bottles, mainly for archaeologists. Archaeological specimens have been used sparingly, however, because of their fragmentary state and often poor preservation; this study has relied for bottle information mainly on examples in private collections.

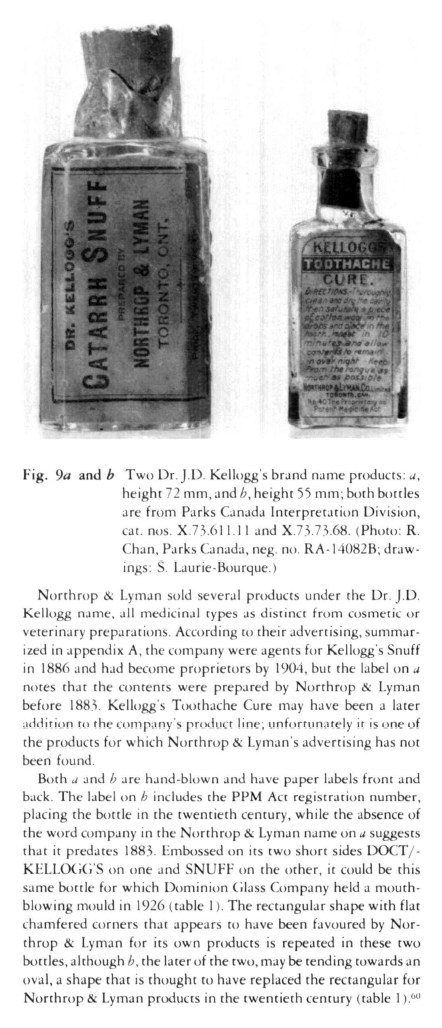

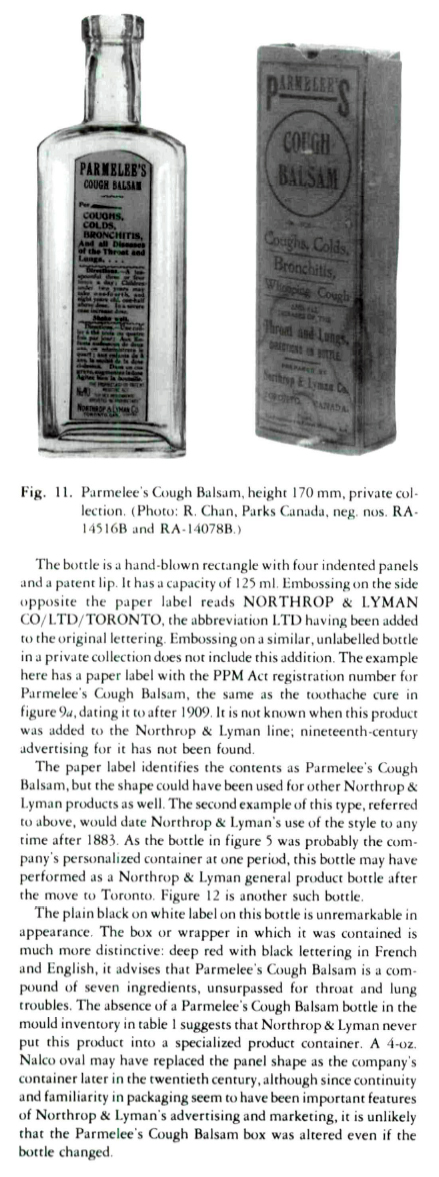

6 Northrop & Lyman bottle labels show that company products began to record a PPM Act registration number, we can assume, in 1909. Originally, this number could be used to register as many products as the proprietor wished — figures 9a and 11 show bottles of different products with the same number — and it is possible that all Northrop & Lyman products at one time carried the same number.8 However, the 1919 amended act required that each product be registered separately, and it is likely that a large number of new registration numbers were created as a result of that amendment.9

7 The company's twentieth-century operations have not been examined to a large extent, and many aspects of its nineteenth-century business are also largely unknown at this time. However, a history of the Northrop-Lyman Company is outlined, the individual retail druggist has been established as the company's main client, and many company products and their containers have been identified.

History

8 The Northrop & Lyman company began business in Newcastle, Canada West, in 1854, as Tuttle, Moses & Northrop.10 The original concern, a retail drug store, was a branch of the American drug firm of Tuttle & Moses, of Auburn, N.Y. By 1857 the company had become Northrop & Moses, wholesale and retail druggists, dealers in patent medicines, trusses, etc. Between 1859 and 1862 John Lyman joined Henry Northrop, buying out Tuttle and Moses, and the partnership was renamed Northrop & Lyman. Northrop & Lyman relocated in Toronto in 1874, apparently because their wholesale patent medicine business required better shipping facilities than were available in Newcastle. Their first address in Toronto, at 40 Scott Street, seems to have been simply a warehouse, but the company moved to a larger facility, with laboratory, at 2111 Front Street West about 1879." By the late 1870s, Northrop & Lyman were being called the largest dealers in patent medicines in the Dominion.12 In 1883, Northrop & Lyman incorporated as manufacturers and dealers in drug with a capital of $100,000; the partners in the company were Henry Stephen Northrop president, John Lyman vice-president, John H. McKinnon secretary, Etna Dene Howe, and George Van Nostrand. Official positions in the newly organized company do not appear to have been assigned to the two junior members. However, Etna Howe was John Lyman's nephew and a bookkeeper by profession, as was John McKinnon, and G. Van Nostrand was a commercial traveller.13 Directories do not note John McKinnon's, Etna Howe's, or G. Van Nostrand's connections with Northrop & Lyman prior to incorporation; however, John McKinnon, bookkeeper, is listed in Toronto city directories in the 1870s and Etna Howe had been a member of John Lyman's household in Newcastle in 1871.

9 Henry Northrop died in Toronto in 1893. Since Northrop & Lyman was a joint stock company, no other change was necessary than to elect a new president and fill the other offices that became vacant as a result.14 John Lyman, who had resided in Syracuse, N.Y., since about 1889, became president and the other officers in the company advanced one position.15 When John Lyman died in Syracuse in 1904, John H. McKinnon became president, Etna Howe vice-president, and George Van Nostrand secretary, but, although both Henry Northrop and John Lyman had died, the company did not change its name.

10 In April 1904 the company's building on Front Street was completely demolished by a fire that destroyed Toronto's wholesale and light manufacturing district. Northrop & Lyman Company occupied temporary quarters during the construction of a new building at 86-88 Richmond Street West until March 1905.16 About 1917, the company again relocated at 462, 464, and 466 Wellington Street West; Northrop & Lyman's most recent address was 2020 Elles-mere, Toronto.17

11 The company's officers were periodically reorganized after the deaths of the two principals, but radical change does not appear to have typified the company. Of the other three original members, nothing is known of G. Van Nostrand after 1906. However, Etna Howe and John McKinnon exchanged positions as president and vice-president, Etna Howe remaining as president until his death in 1920, by which time John McKinnon was no longer with the company. A newer member, William Fraser, clerk with Northrop & Lyman since 1897 and eventually Etna Howe's son-in-law, served as treasurer under Etna Howe and then secretary and vice-president under Etna's son, Herbert J. Howe. By 1914, Northrop & Lyman had become a Howe family business, for in that year we find M.B. Howe, possibly Etna's wife Martha, director, Herbert J. Howe secretary, Lyman P. Howe clerk and Harold D. Howe bookkeeper for the company. Herbert Howe's presidency began with his father's death in 1920 and continued until 1951. In that year the company was reorganized under the same company name, with Thomas A. McGillivray, formerly general manager for Lehn & Fink and before that of McGillivray Bros. Ltd., as manager.

12 The McGillivray connection with Northrop & Lyman may have been a family one, for a John R. McGillivray travelled for the company between 1895 and 1900, and John Lyman's will bequeathed $2,000 to a Tena McGillivray of Syracuse in 1904. During the mid-1960s, the company name was changed to Northrop-McGillivray. Its history from that point has not been traced, but Northrop-McGillivray seems to have been in business until at least 1980.18 Research on the company's twentieth-century operations has not been undertaken in any depth.

13 At its peak, the company was extremely successful, selling its products throughout Canada and in the West Indies, Newfoundland, South America and Australia. Both Henry Northrop and John Lyman, whose beginnings were humble, were wealthy men at the time of their deaths.

Advertising and Marketing

14 Henry Stephen Northrop and John Lyman began the drug business as commercial travellers for the wholesale firm of Tuttle & Moses of Auburn, N.Y.20 Since both men always listed their professions as merchants, it is not unreasonable to believe that neither had formal pharmaceutical training, and that both were more familiar with wholesaling than retailing. The choice of Newcastle in which to locate a retail outlet that became a wholesale business should be considered.

15 During the 1840s the value of farming land in the District of Newcastle increased steadily with a growing population of British immigrants interested in wheat farming. Towns and villages on navigable water routes were becoming populated business areas. Bond Head, a village and shipping place on Lake Ontario, relied for its services on the village of Newcastle, one-and-a-half miles distant in 1844. By 1851, Bond Head was considered to be a part of the village of Newcastle, and before 1857, Newcastle's amenities included a train station.21 The Canada Directory for 1864 describes Newcastle:

16 Thus, Newcastle had to recommend it a port and a train stop that guaranteed traffic through the town as well as the potential for shipping and receiving freight, proximity to suppliers in New York state, and an expanding local population.

17 The flourishing of the Northrop & Lyman partnership at the early period has been credited to the indefatigable efforts and personal qualities of John Lyman, who travelled extensively for his company and established friendly relations with his customers. Obituaries for John Lyman and for Henry Northrop suggest that the former was better known in the trade than his partner, and the tasks involved in the business may have been divided into public and low-profile responsibilities. In addition to John Lyman, others of the five adult males employed at Northrop & Lyman's Newcastle factory in 1871 may have been engaged in commercial travel for the company; census records for that year show a commercial traveller named William Farewell (?) in Henry Northrop's household.23 Personal contact with clients in the company's early days can be assumed to have been an important feature of the business. In fact, anecdotes concerning John Lyman's personal appearance, his early life, his endowments to hospitals on behalf of his three dead children, and details of his bequests to charities, all considered newsworthy at the time of his death in 1904, suggest that personal contact was a feature of the business throughout its most successful period.24

18 The role of Toronto as a trading centre during the mid-nineteenth century has been discussed by Middleton and Landon. Their observations suggest that operating out of Newcastle would have become increasingly disadvantageous. Toronto, competing with Montreal for the business of newly established settlements in Ontario, was developing as a main distributing area at the expense of smaller towns. Many country merchants preferred to select goods personally from the warehouses of their wholesalers, and businesses located in Montreal and Toronto were favourably placed for selling to visiting buyers.25 Northrop & Lyman appear to have followed this pattern, in that their original establishment in Toronto, on Scott Street, was a warehouse. The factory in Newcastle may have continued to supply their products before acquisition of the Front Street laboratory about 1879. Front Street was an excellent business address in an area that was to become the wholesaling and light manufacturing district in Toronto. In 1904 the area was completely destroyed by fire. A late nineteenth-century description of their Front Street facility calls the laboratory "one of the largest and best equipped in Canada." It also notes that seven travelling salesmen were connected with the company at that time, and that the company's name and reputation were recognized by the trade.26 The last item is interesting, since it suggests the market to which Northrop & Lyman advertising was addressed.

19 The highly competitive, nineteenth-century patent medicine business forced all levels of merchants involved — manufacturers, druggists, jobbers, and wholesalers — to vigorous and imaginative advertising.27 Although an extensive search of daily journals has not been undertaken, a general impression has been formed that Northrop & Lyman did not advertise their products to the public in this way. Northrop & Lyman did advertise in directories and gazetteers, but individual products are not celebrated in these sources, and these advertisements are fairly discreet, consisting of a few lines naming the company, type of business, and location.28 Northrop & Lyman's advertising seem to have been directed at the druggist through the company's commercial travellers, trade papers, and by lending company support to druggist's interests, such as the cut-rating issue.29

20 During the 1890s, Ontario pharmacists waged war with dry goods store owners who were expanding their trade to include patent and proprietary drug products. One of the leaders in this direction was the T. Eaton Company of Toronto, which not only sold the goods that druggists considered their exclusive sphere, but also undercut listed prices by 20 to 25 per cent. The Northrop & Lyman Company was among the group of "druggists' friends" who agreed not to deal with the cut raters, although Northrop & Lyman goods were sold through Eaton's mail order catalogues, presumably having been supplied by other wholesalers. The threat posed to druggists by cut-rating can be demonstrated with prices for one of Northrop&& Lyman's leading products, Canadian Hair Dye:

Northrop & Lyman suggested retail price (1904) .50 each

T. Eaton catalogue (1905) .35 each30

The conflict seems not to have been resolved formally, but catalogues show that Eaton's increasingly replaced brand name products with its own goods, and T. Eaton medicine bottles on Canadian sites and in other types of bottle collections are not rare.

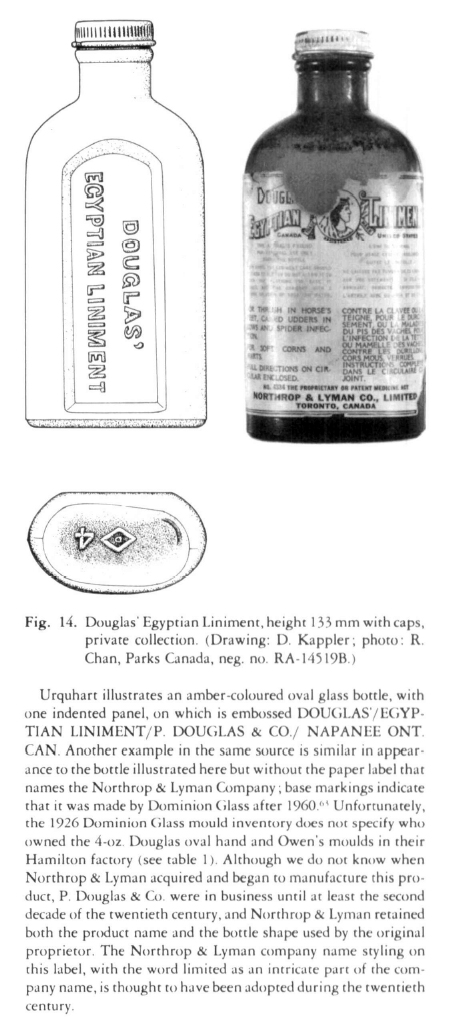

21 The independent druggist was an important aspect of Northrop & Lyman's marketing, receiving much of the company's advertising attention. Northrop & Lyman almanacs, such as one dating from 1886, include testimonials indicating that druggists were in the habit of diagnosing illnesses and complaints and of recommending specific products to their customers.31

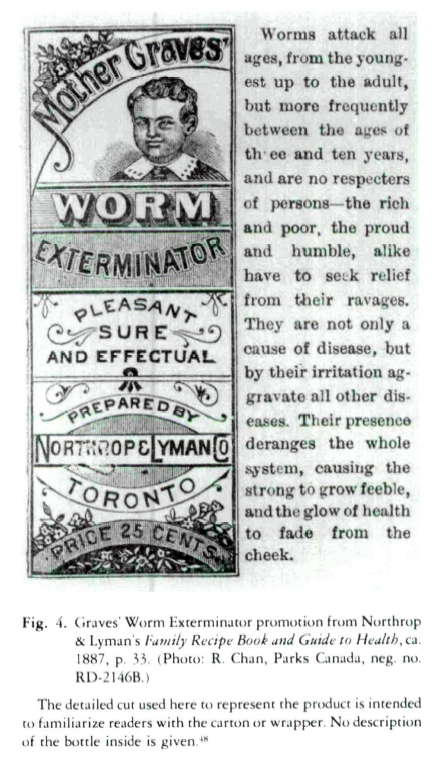

22 Patent medicine almanacs and their impact in the American household have been discussed by Young, who dates one of the earliest, on behalf of Bristol's Sarsaparilla, to 1844.32 Four Northrop & Lyman almanacs have thus far been seen, from 1886, ca. 1887, 1902, and 1904.33 Since a year's calendar is a part of each almanac, Northrop & Lyman probably published a new almanac each year. These pamphlets were produced with the consumer in view; they contain information on a limited number of Northrop & Lyman's products, with a preamble concerning the symptoms and nature of various maladies, testimonials to the product's efficacy, said to be unsolicited, and usually an illustration of the package. The illnesses are those of the time: consumption, tetanus, blood-poisoning, worms, catarrh, and the public is admonished to have always on hand the means of combating sudden illness and accident. There is diversion in items of humour, puns, and the like, often cooking recipes, and a calendar of the year, including historical events and forecasted weather trends. The back cover usually has a space to insert the druggist's name.

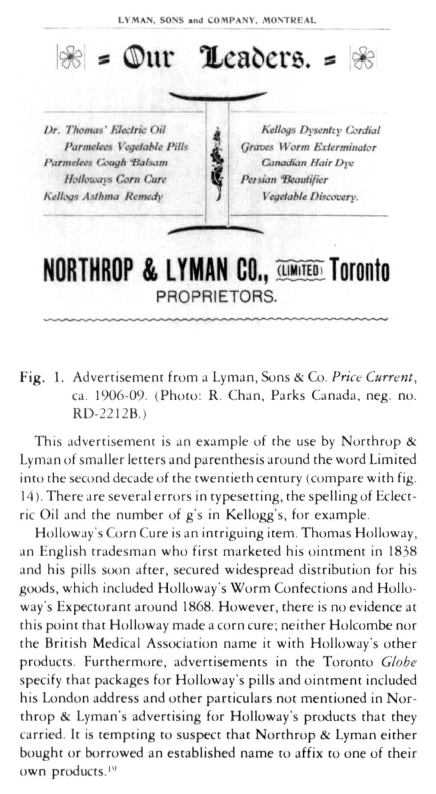

23 In addition to almanacs, Northrop & Lyman advertised to the public through sample vials such as that illustrated in figure 2. We do not know whether samples were provided to the druggist or delivered to private homes by the company, although since other advertising was directed at druggists, it is more likely that the commercial travellers gave samples to the druggists for distribution to the public. Free product samples continue to be an aspect of pharmaceutical advertising and may have been used throughout the company's history. As in other areas of the study, a picture of Northrop & Lyman's twentieth-century operations is not complete and certain aspects from an earlier time are missing as well.

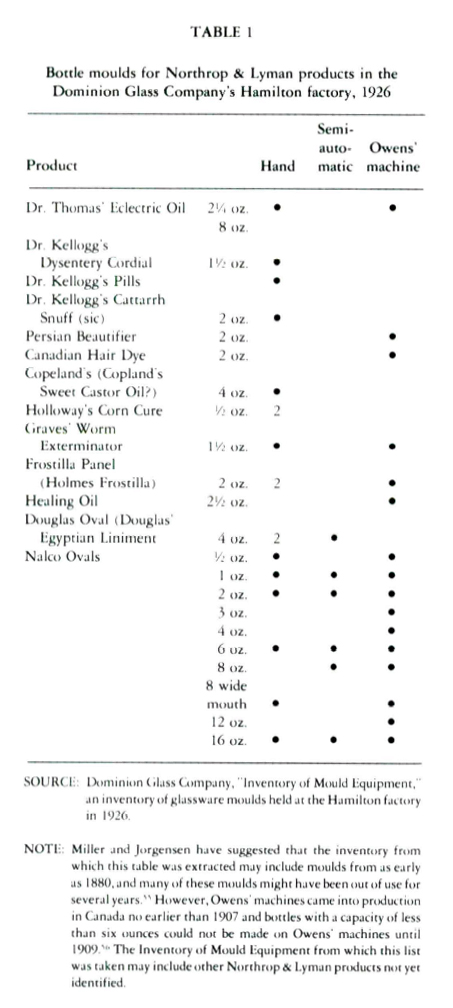

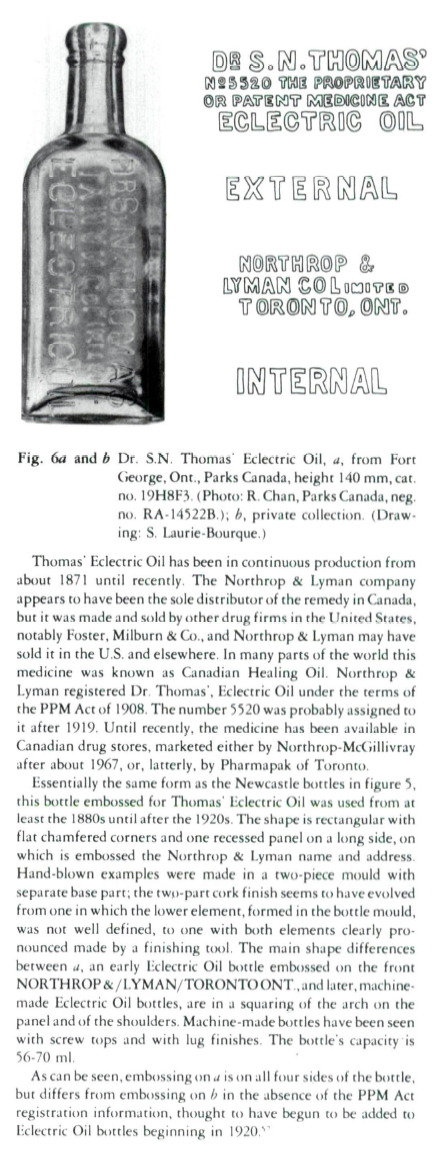

Display large image of Figure 1

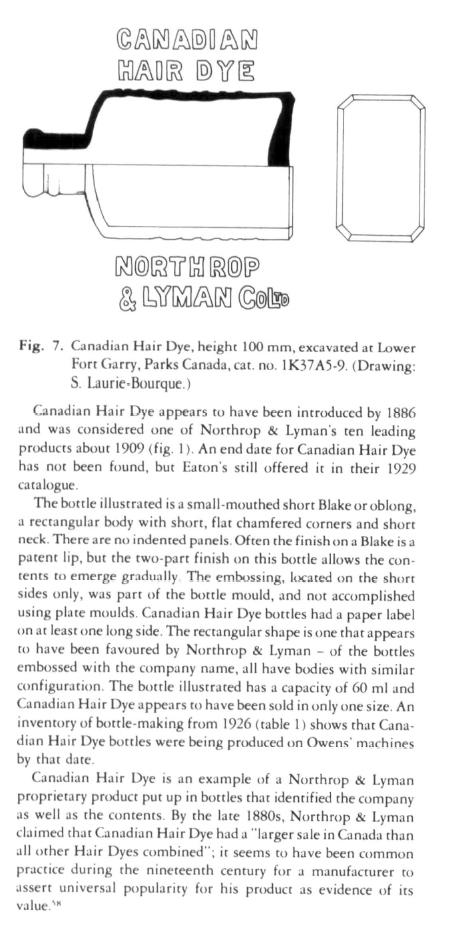

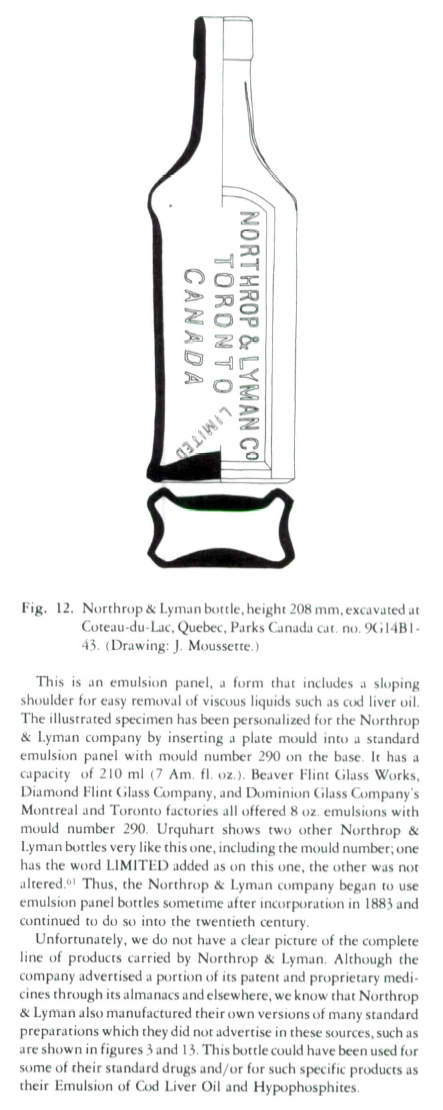

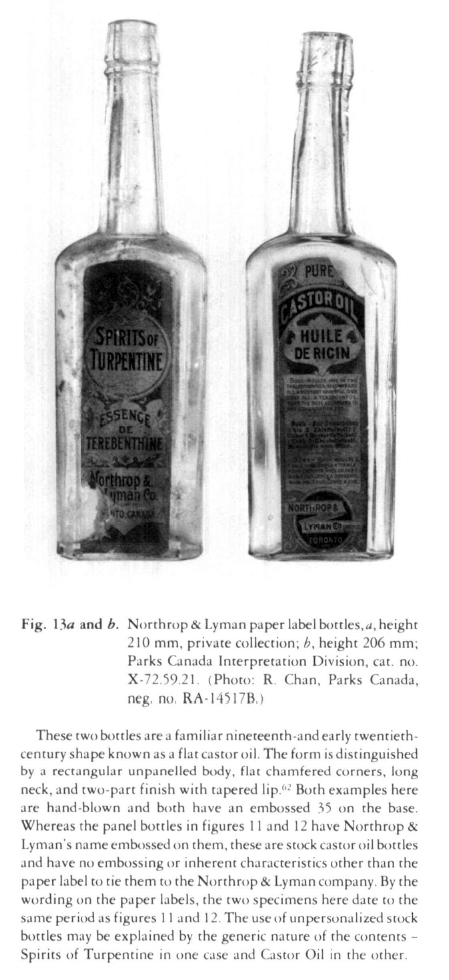

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

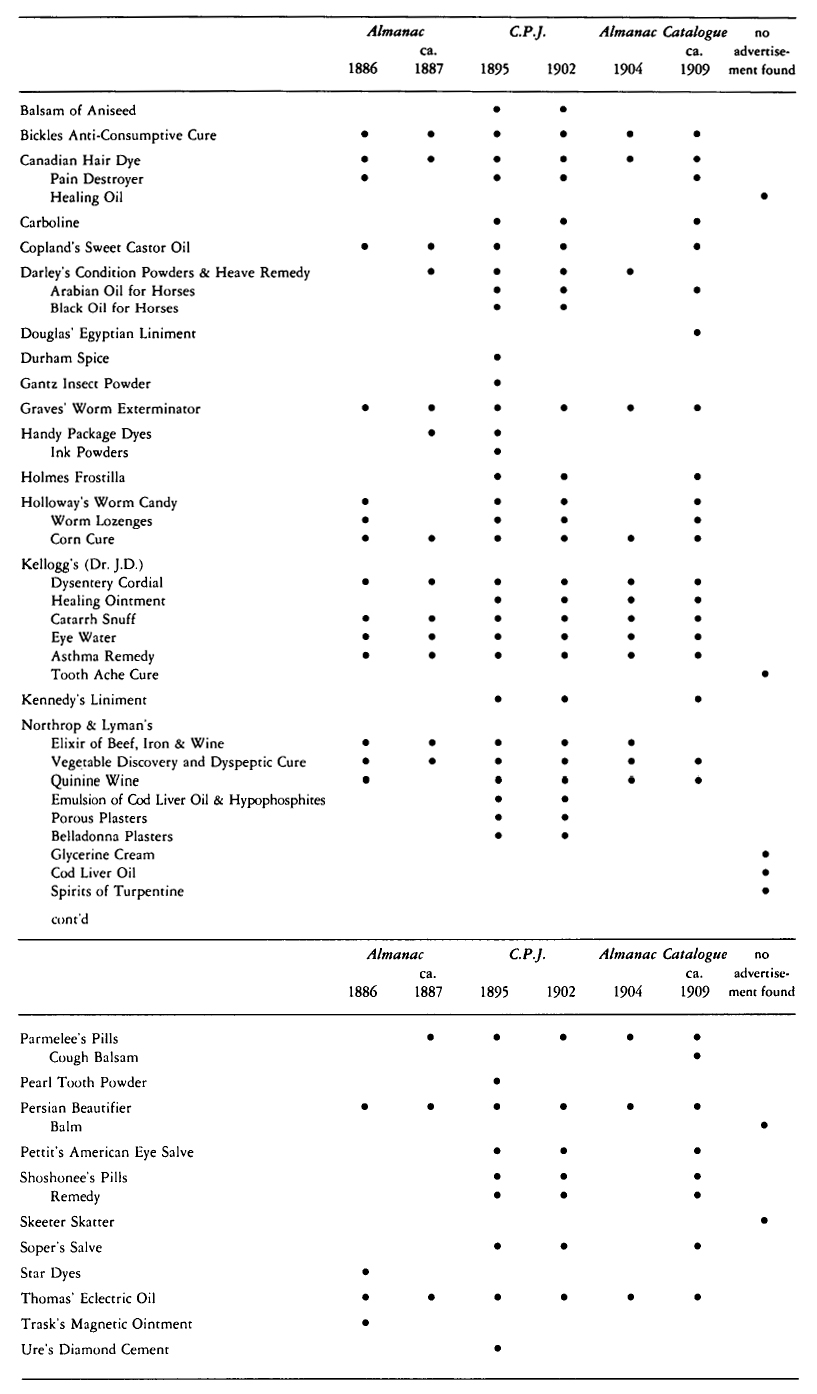

Display large image of Figure 224 We know that Northrop & Lyman used broadsides to advertise specific products, advertised in trade journals such as the Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal, and purchased space in the pages of other wholesalers' catalogues (fig. 1).34 However, druggists' circulars, catalogues, and price currents put out on behalf of Northrop & Lyman products have not been located from either the nineteenth or twentieth centuries, and we do not know when the company began and stopped producing almanacs.

25 Two important elements in the company's early success were timing and experience. Canadian directories and business gazetteers show Northrop & Lyman to have been among the first of the large patent medicine dealers in Canada. In 1877, only two other companies were noted as specializing in patent medicines, whereas by the 1890s, Northrop & Lyman were in competition with several. The company's American parent drug firm had trained both John Lyman and Henry Northrop in the business; the Canadian company appears to have been up-to-date and to have adapted to trends in the drug trade. Northrop & Lyman's manufacturing facility, referred to in Newcastle as a factory, was called a laboratory in Toronto, a shift in the company's emphasis which seems to have paralleled one in the trade.35 The company's use of bottles marked with its name, beginning early in its history, probably added to the company's reputation; druggists interviewed in the early twentieth century were inclined to trust wholesale manufacturers who willingly acknowledged their own products to the public.36 However, many of the practices that contribute to Northrop & Lyman's good reputation with the nineteenth-century trade became law in the twentieth century under the conditions of the PPM Act of 1909.37

The Products

26 The company's stock in its retail drug store in Newcastle would have been simple or elaborate, depending on the ability to procure raw materials and prepared goods, and the druggist's enterprise in compounding his own mixtures. Since the original business was a branch store, we can assume that many of the goods sold in Newcastle were supplied by the parent company. Unfortunately, information on Tuttle & Moses of Auburn, N.Y. has not been located and their product line is not known. Other goods sold to the local population would have been prepared in the store to fill family prescriptions, and some articles would probably have been compounded on a larger scale, as was customary at the period, to save money. Neither Henry Northrop nor John Lyman appear to have had pharmaceutical training themselves, but Henry Northrop's household in Newcastle in 1861 included a 28-year-old, English-born druggist, whose hand-written name on the census record is not legible.39 It has been said that the druggist in attendance in Newcastle specialized in veterinary preparations, and the Darley brand name products that Northrop & Lyman carried at a later time may have originated with this druggist and been manufactured continuously from the company's early days (see Appendix A).40 Directory listings show that Northrop & Moses retained the retail operation of their business in 1857, but by the 1860s the company appears to be exclusively wholesale.41 By 1871 Northrop & Lyman operated a patent medicine factory in Newcastle that employed on average 11 people and paid yearly wages of $3000.42

Display large image of Figure 3

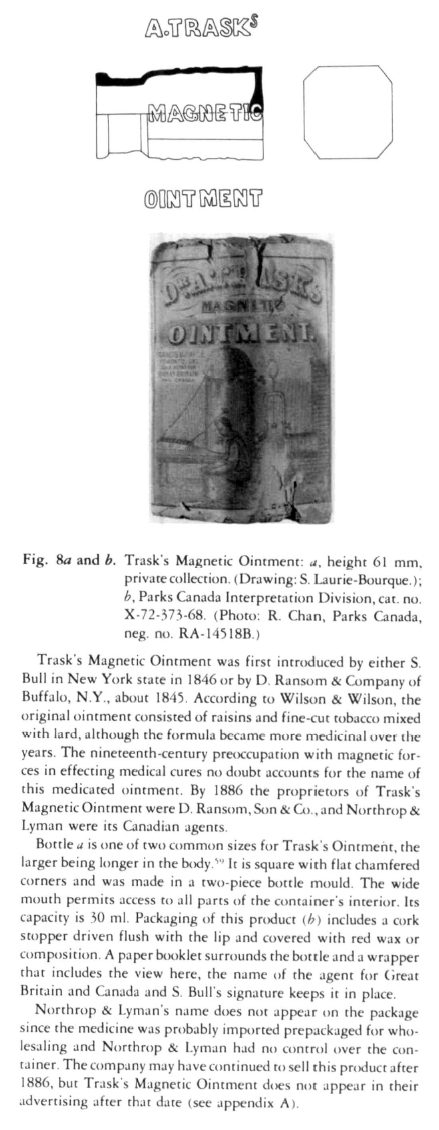

Display large image of Figure 327 The company's product line by the 1870s included goods for which they were Canadian agents, such as the Dr F. C. Ayer & Co. medicines — Ayer's Cherry Pectoral, Ayer's Sarsaparilla, Ayer's Ague Cure, Ayer's Hair Vigor—and a line that Northrop & Lyman manufactured themselves, the Canadian brand, Canadian Pain Destroyer and Canadian Hair Dye, beginning in the late 1860s, and Thomas' Eclectric Oil beginning about 1871. The manufacturing aspect of their business was increasing during the 1870s, and by the 1880s Northrop & Lyman were also either preparing or having made for them, Graves' Worm Exterminator, Northrop & Lyman's Vegetable Discovery and Dyspeptic Cure, Northrop & Lyman's Beef, Iron, and Wine, Copeland's Sweet Castor Oil, Star Dyes and Holloway's Corn Cure, and were agents for several products, including Dr. Trask's Magnetic Ointment, Dr. Kellogg's Catarrh Snuff and others.43 Appendix A, listing Northrop & Lyman products, has been compiled from company almanacs and advertisements in the Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal. Although the Ayer products, sold by Northrop & Lyman before 1877, did not continue to be advertised by the company in later years, it is possible that Northrop & Lyman continued to carry them, since advertisements for other medicines and toiletries known to have been sold by the company have also not been seen. Parmelee's Cough Balsam, for example, was noted as one of the company's 10 leading products in the twentieth century (fig. 1), and Kellog's (sic) Pills bottles were manufactured by Dominion Glass Company before 1926 (see table 1); Northrop & Lyman advertisements were not found for either of these products. Northrop & Lyman carried other goods of which we have no advertising record, including dozens of standard patent medicines, bay rum, perfume, ointments, elixirs, etc. Their product line probably amounted to a full complement of druggists' goods.

28 Some idea of what this involved can be gained from nineteenth-century British, Canadian, and American pharmaceutical trade journals, such as The Chemist and Druggist, the Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal and The Druggists' Circular, with portions of each issue devoted to recipes for items that druggists might need to compound either on a regular basis or less frequently. The editor of The Chemist and Druggist, a British trade paper, compiled a particularly varied formulary in response to requests for such a work by subscribers to the journal. Originally published in 1898, MacEwan's Pharmaceutical Formulas: A Book of Useful Recipes for the Drug Trade went through several editions, three of them in its first year of printing.44 His formulary of proven, oft-requested recipes and notes on modern packaging and display indicates that the business of the druggist had become very complex by the end of the nineteenth century. Included are procedures for concocting face powders, lotions, perfumes, lip salves, cordials, effervescent beverages, inks, veterinary preparations, agricultural specialities, cements, liquid glues and mucilage, fireproofing solutions, vermin poisons, household products, dental and other toilet preparations, and galenic remedies, among others. That this broad range of items was the domain of the druggist is confirmed by druggists' glassware catalogues of such firms as Whitall, Tatum & Co. of Philadelphia, which sold containers for all of these goods and could individualize some bottles by embossing the druggist's name on them.45

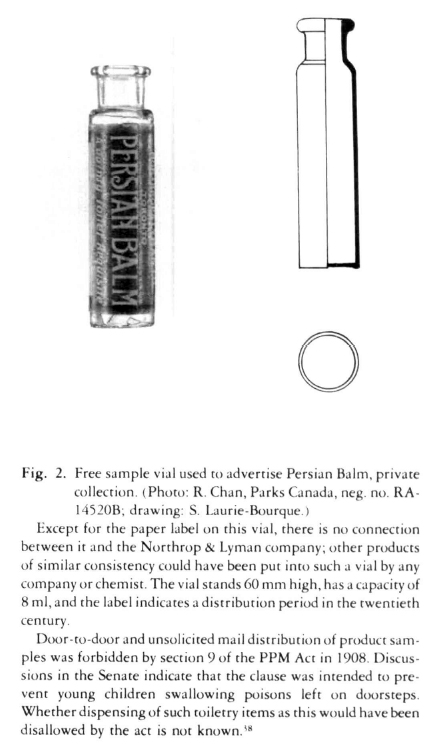

29 Not every druggist and dry goods dealer had time or inclination to make his own preparations so would have purchased many from pharmaceutical firms. Northrop & Lyman's lists of goods include most of these types of preparations with the exception of effervescent beverages: brand name hair and toilet products, animal remedies, liniments, tonics, cough syrups, ink powders and dyes; figures 3 and 13 show the class of generic goods that druggists could prepare using formularies or purchase in bulk — glycerine cream, castor oil, etc. In these items, Northrop & Lyman would have been in competition for sales, not only with the individual druggist, but with other drug houses — National Drug Co., Elliot & Co., Parke, Davis & Co., Davis & Lawrence, the T. Eaton Co. drug department, Lyman Brothers & Co., Henry K. Wampole, and others, all of whom sold their own versions of standard preparations — and with companies, such as the Seely Manufacturing Company and W.T. Atkinson & Co., that specialized in one type of goods, in this case, toiletries and cosmetics.

30 The Northrop & Lyman Company seems to have specialized during the twentieth century in insect repellents, such as Skeeter Skatter, and household products such as Lemmonia.46 Thomas' Eclectric Oil continued to be a Northrop & Lyman product and was also sold by Northrop-McGillivray (see fig. 6). As well, the company continued to add products to its line into the twentieth century, such as Douglas' Egyptian Liniment (fig. 14), a veterinary remedy. The Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act of 1908, the details of which will not be discussed here, required that all products for sale in Canada be registered and a yearly registration fee paid.47 Unfortunately, although the PPM Act was revoked during the 1970s, the information is still considered protected by the terms and conditions of the original act, and is not available to the public. Accessibility to these records could provide the names of the products sold by this company, as well as the dates at which products were started and stopped.

The Bottles

31 Among the marketing devices used by patent medicine proprietors since the eighteenth century is distinctive packaging.49 The need to make a particular product recognizable to the consumer led in some cases to elaborate container shapes, such as Turlington's Balsam of Life. Advertising by the proprietor would then include a description or illustration of the package along with promotion of the product. Northrop & Lyman used personalized, marked bottles for their goods beginning in Newcastle, but appear not to have apprised the consumer that they did so. Instead, Northrop & Lyman's advertising in their almanacs attempted to fix in the consumer's mind, through written descriptions and illustrations, the appearance of the box or wrapper (fig. 4). Implicit in these descriptions is that the proper package, with the proprietor's signature, is the purchaser's only guarantee of the content's genuineness; explicit is that unscrupulous people will copy a good product and fool the unwary into purchasing the imitation by using a similar name and packaging. Occasionally, Northrop & Lyman provided a description of the medicine — Parmelee's Pills, for example, were gelatin-coated and covered with licorice flour to preserve and make them palatable — but shape, size and configuration of the glass bottles is not usually detailed in Northrop & Lyman's advertising literature.50

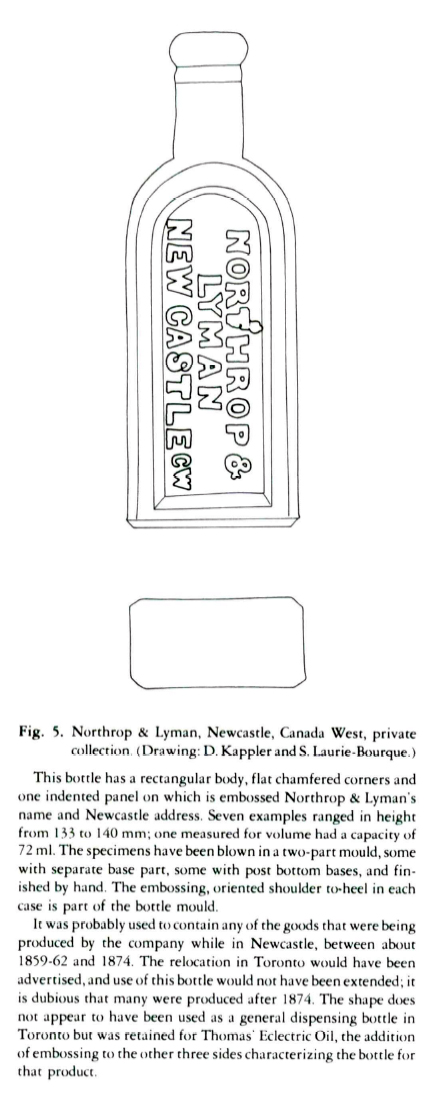

32 Northrop & Lyman began to use bottles embossed with their company name early in their history, probably during the 1860s. As far as we know, these bottles could have contained any of the products that the company was making before 1874 when it relocated in Toronto. Of the seven Northrop & Lyman Newcastle bottles that have been seen, none are empontilled, all are the same size, and, most significantly, none has been marked with a product name (fig. 5). While many Northrop & Lyman products are likely never to have been put into specialized product bottles, others had containers of specific design associated with them.

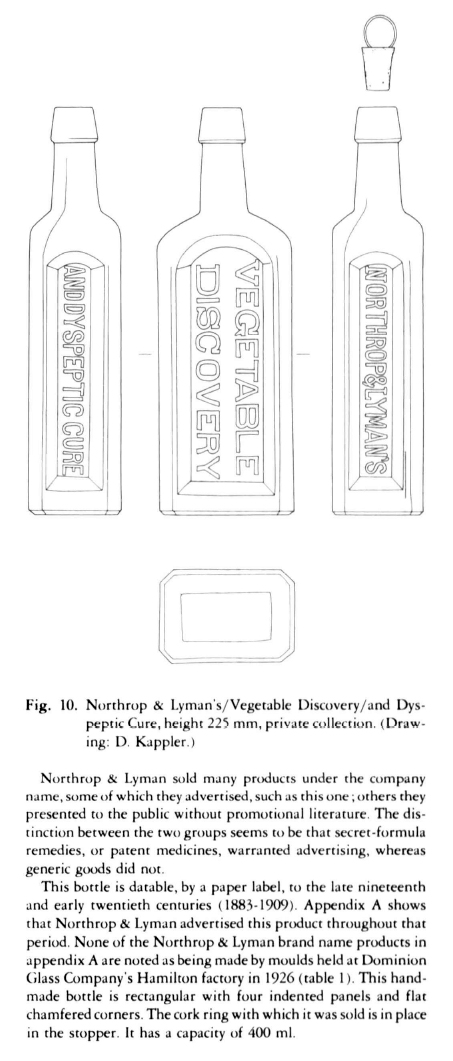

33 Once established as a product container, specialized bottle forms seem to have been retained over an extended period without substantial alteration to the shape. Some Northrop & Lyman products introduced in the 1860s and 1870s were put up in bottles made on Owens machines in the twentieth century (table 1); in many cases, the machine-made version resembled the hand-blown bottle. Thomas' Eclectric Oil bottles, for example, had the same form and general configuration from before the 1880s until a standard-shaped dispensing oval was adopted for the product some time around World War Ⅱ.51 Continuity of bottle form was also maintained for products acquired at a later period from other proprietors. Northrop & Lyman put Douglas' Egyptian Liniment into a container similar to one already associated with the product by its originators, P. Douglas & Co. (fig. 14). On the other hand, the Northrop & Lyman company had no control in the packaging of remedies for which they were agents, such as the Ayer products and Trask's Ointment (fig. 8).

34 For products that Northrop & Lyman owned, rectangular bottles, some with panels, seem to have been preferred. Thomas' Eclectric Oil, Graves' Worm Exterminator, Canadian Hair Dye, Northrop & Lyman's Beef, Iron, and Wine, Kellogg's Catarrh Snuff, and others were all put up in regular bottles. Embossing on Northrop & Lyman bottles varies with the item: Thomas' Eclectric Oil bottles have raised letters on all four sides; Graves' Worm Exterminator and Kellogg's Snuff are embossed on the two short sides only; Parmelee's Cough Balsam and the emulsion panel in figure 12 are embossed with only the company name; the castor oil shapes in figure 13 have no embossing at all.

35 A difficulty in dating Northrop & Lyman bottles is that the company's history spans the century between the general adoption of some significant hand-blown bottle-making tools, such as the snap case and the finishing tool, and the end of hand-blown bottle manufacture as a result of complete mechanization in the container industry. As well, different types of products are represented in Northrop & Lyman bottles. Dating can be undertaken, within fairly broad ranges, by the Northrop & Lyman company name styling and the location of the business, Newcastle having been used, it is supposed, after 1859-62 and before 1874. Between the time of the move to Toronto and the company's incorporation in 1883, NORTHROP & LYMAN TORONTO ONT appears to have adequately identified the company, COMPANY or its abbreviation, CO, having been added after incorporation in 1883. During the second decade of the twentieth century, Northrop & Lyman began to include LIMITED as part of the company name, embossing on older bottle moulds being altered to include the word or abbreviation of it. Figures 11 and 12 show bottles on which LIMITED or LTD has obviously been appended to an earlier name styling; in both cases, other specimens which pre-date the alteration have been seen. The Canadian Hair Dye in figure 7 has also been modified by the addition, the abbreviation having been squeezed into a space almost too small for it.

36 Updating the wording on an older hand mould would, no doubt, have extended its life into the twentieth century. However, table 1 shows that the Northrop & Lyman company purchased semi-automatic and Owens' machine moulds for many older patent medicine bottle types and discontinued others.52 If these medicines continued to be made and sold, it is probable that the company began to package them in personalized company bottles rather than specialized product bottles. In addition, table 1 shows a shift in Northrop & Lyman's personalized bottles from the panels and rectangles of the nineteenth century to an oval shape. The ten sizes of Nalco oval, including one with wide mouth, may have served the function that the bottles in figures 11, 12, and 13 had performed after 1883 and sometime before 1926. Unfortunately, a description of a Nalco oval has not been found, but Northrop & Lyman products obviously had market enough to justify the expense of mechanized private moulds.

37 The glass bottles illustrated in the following pages have been chosen for inclusion primarily because they were readily identifiable as Northrop & Lyman containers; many include the company name on the bottle, but others are associated with Northrop & Lyman by another brand name. Archaeological assemblages from Parks Canada sites, private collections, and the Reserve Collection held in Ottawa by Parks Canada's Interpretation Division provided the specimens. The representation of Northrop & Lyman bottles is surprisingly small, considering the implied volume of business during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but even less known are the containers used by Tuttle, Moses & Northrop and Northrop & Moses, if indeed, any such exist.53 Since this study's focus is on containers made of glass, those of other materials, such as ceramics (fig. 3), metal,54 and paper have not been considered here. However, it is expected that the products noted in appendix A in combination with the following list will help in the recognition of other Northrop & Lyman bottles, and this study is viewed as an initial history of the Northrop & Lyman company.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14APPENDIX A

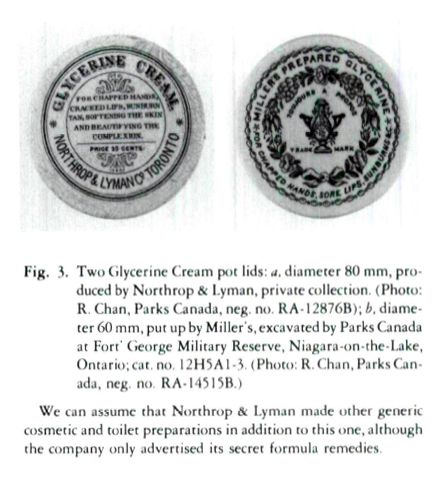

38 Northrop & Lyman advertised brand name products. Although the list includes products whose function is obvious from their names - household preparations, toiletries, veterinary medicines - the purpose of many of these goods is not known at present. Therefore, they have been arranged alphabetically rather than by type of article. The date of publication of the source in which the item occurs is noted across the top (Northrop & Lyman, Almanac, 1886, ca. 1887, 1904; Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal, 1895, 1902; Lyman, Sons & Co. Catalogue, ca. 1909); the last column is of products for which no advertising has been seen. The type of packaging varies, and not all were contained in glass bottles.

* I wish to thank the following for providing material used in this study: Lois Logan, secretary to the president of National Drug Limited; Dr. Ernst W. Stieb, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto; Mr. & Mrs. Shorter; Mr. & Mrs. Thomson; Carl Fox; Christine Mosser and David Kotin, Canadian History Department, Metropolitan Toronto Library; William Ormsby, archivist of Ontario; Interpretation Division, Parks Canada, Ottawa; Deborah Trask, Nova Scotia Museum; Gerald Parsons, Onondaga County Public Library, Syracuse, NY.; Ann P. Barry, Gmnecticut State Library; George L. Miller, OliveJones.John Light, Ann Smith, and Karlis Karklins, Parks Canada, Ottawa. Elizabeth Jorgensen was a patient assistant in the tedious task of searching through directory listings, and Olive Jones and George Miller provided guidance.direction, and advice on a subject that was discouraging to research because of the difficulty in locating information.