Collections

National Museum of Man:

History Division Ceramics Collection

1 The History Division of the National Museum of Man has among its holdings some 4,000 examples of earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain, dating from the eighteenth to the twentieth century and ranging from Canadian-made storage jugs to imported toy services. Most of this collection, which reflects a broad spectrum of socio-economic levels, has been acquired during the last ten years, and, as with most collections, there remain areas to be strengthened. As a whole, however, the collection fulfils the aim of illustrating the types of ceramic wares used in Canadian homes across the country.

2 Artifacts for the collection are chosen because they can be documented as a type available in an area at a point in time, or because they come with an established history of ownership in a Canadian family. In the category of under-glaze, transfer-printed earthenware, for example, the collection includes a plate with a view of the Chaudière Bridge (after W. H. Bartlett) from a Staffordshire table service owned and used in Montreal by the Dawson family.1 Sir William Dawson (as he became) and his wife brought the service with them from Pictou, N.S., to the principal's residence at McGill University in 1855. Later, what remained of the service went to the Dawson summer home, "Berkinshaw," at Métis, Québec. It was inherited by granddaughters and through one of them, Mrs. Lois Winslow-Spragge, the plate entered the national collection.

3 In this same category of printed earthenware (the wares most commonly found in Canadian homes in the nineteenth century) the collection includes a part service in a floral pattern, slightly earlier than the Dawson plate, which can be documented as having been sold originally in Québec City: two of the pieces have printed on the back the name of Samuel Alcorn, whose Crockery and Glass Store was at 13 Palace Street.

4 Wares carrying the names of Canadian importers are discussed elsewhere in this Bulletin, but one further example from the collection is worth mentioning as a reminder that in the history of the Canadian ceramic trade Tyneside potters were active competitors of Staffordshire. This blue-printed platter, ca. 1835, with the name of the Halifax china merchant, Bernard O'Neill, was made by Thomas Fell and Company, of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The strong showing of Tyneside potters in the Canadian market can be documented from advertisements in newspapers published in port cities, such as Halifax and Québec. The material evidence turns up in artifacts such as the platter.

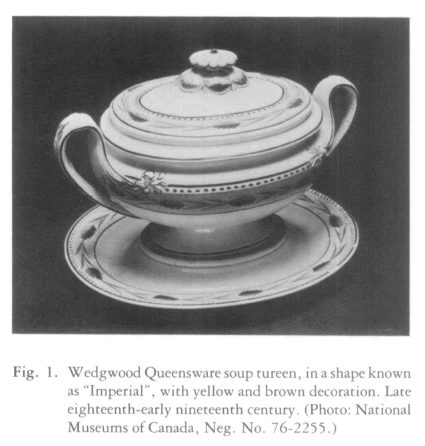

5 Among the earlier earthenwares is an impressive pair of Wedgwood soup tureens (Wedgwood's Queensware) from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century2 (fig. 1). Table services of this type were advertised in Canadian newspapers; they were also brought to Canada for use by officers of the garrisons (the Royal Fusiliers at Québec in the 1790s, for example), and by colonial governors (Sir Robert Shore Milnes).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 56 At the other end of the scale are plain, white, ironstone tablewares, which are well represented in the collection. A piece that illustrates not only a ware that was tough, durable, and in use from St. John's to Victoria, but emphasizes another aspect of the Canadian trade is an 1860s jug that falls into the category of "seconds" (wares that left the manufactory in imperfect condition and consequently sold cheaply). "Seconds" constituted a sizeable part of the ceramic trade in a country where new settlers often had little to spend on even the necessities of house furnishing. In 1862 the Toronto Board of Trade's Annual Report stated: "We continue to be considerable importers of ... 'seconds,' a description of goods ... much cheaper than the 'firsts.'"3 The maker of the jug was Liddle Elliot and Son, a Staffordshire firm with a resident agent in Canada in the 1860s.

7 Earthenwares, including ironstone chinas and sponged wares (the so-called Portneuf which came in large part from Scottish potters), account for the greater proportion of the imported wares in the collection. The porcelains, a smaller group, comprise Chinese export (advertised in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Canada as "Nankeen" or "India China"); eighteenth-century English porcelains, such as Worcester (advertised in exchange for furs in Saint John, N.B., in 1790); the "New English China" (as the first Canadian advertisements spoke of bone china); and continental porcelains, especially the hard paste porcelains from Limoges, France, which had immense popularity from about the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

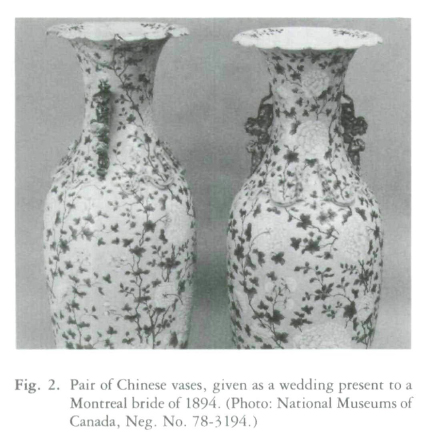

8 The ornamental wares are of many types. Particularly interesting is a pair of large vases, Chinese in origin and typical of a type of ornamental wares seen in fashionable Canadian settings in the late nineteenth century. These vases (fig. 2) were given to the niece of Lord Mountstephen on her marriage in 1894 by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company's representative in the Orient. Their documentation (they were acquired from a granddaughter of the 1894 bride) includes a photograph showing them in the original owner's house on Drummond Street, Montréal, in 1931.4

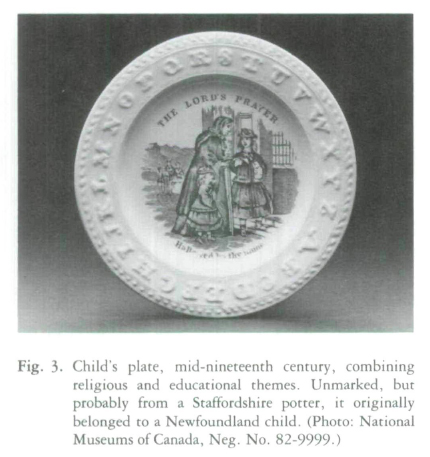

9 Wares made for the use and amusement of children are well represented. An interesting group of children's plates, mid-nineteenth century in date, with a history of ownership in Newfoundland, was the gift of Mrs. Eugene Forsey; they belonged to Dr. Forsey's family5 (fig. 3).

10 An essential part of the collection is devoted to wares made by Canadian potters. Ontario and Québec are particularly well represented, and the collection includes not just examples of all the common wares produced but notable rarities. Ontario had the greatest concentration of potters in nineteenth-century Canada, and the largest number of artifacts come from these potters, the collection having been greatly augmented in 1981 by 241 pieces obtained from a private individual.6 Almost half the total number of pieces were marked examples, one being a dog figure with the 1859 patent mark of J. and W.O. Brown and Company, who potted in the Toronto area. A spectacular piece in the Ontario group is a red ware pitcher from the Brownscombe pottery in Bruce County.

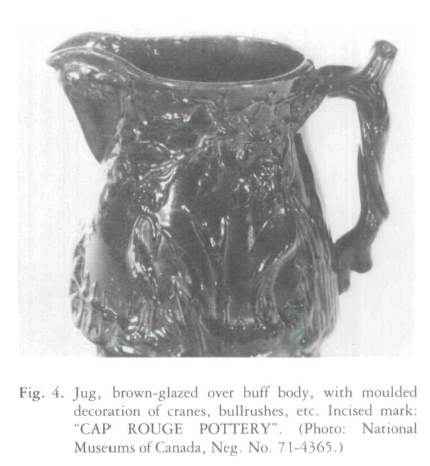

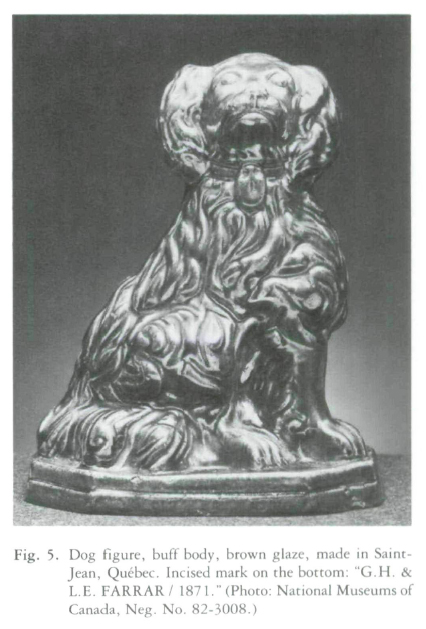

11 Québec wares include rare marked examples from the Cap Rouge Pottery (fig. 4). Another rare item is the only recorded example of an ornamental dog figure that can with certainty be attributed to the Farrars of Saint-Jean. This figure is not only marked (G.H. & L.E. FARRAR) it is also dated (1871)7 (fig. 5). The St. Johns Stone China-ware Company, founded in 1873, was the only really successful maker of white wares for the table in nineteenth-century Canada. The collection has a large selection of wares from this Saint-Jean pottery, as well as examples from its local competitors, such as the short-lived British Porcelain Company.

12 The Canadian section also includes wares from the important Foley Pottery in Saint John; and, moving to the twentieth century, there is a large grouping of Alberta wares from the Medalta Pottery in Medicine Hat.

13 Persons desiring further information concerning the ceramics collection of the History Division should contact Judith Tomlin, at the History Division, National Museum of Man, Ottawa, K1A 0M8.