Articles

Eighteenth-Century Coarse Earthenwares Imported into Louisbourg*

Abstract

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries coarse earthenwares were mass-produced for colonial export markets. These commonly found wares serve as good chronological indicators for the archaeologist, contribute social and economic interpretive information on the residents and their society in general, and indicate or confirm trade connections. This paper is a study of the coarse earthenware recovered from a dated context within the interior of a house located in the townsite of the Fortress of Louisbourg.

The artifacts examined are dated to ca. 1745, the time of the first English and New England invasion of the colony. The material represents a relatively large and intact artifact assemblage having a good variety of ware types, shapes/functions, and ascriptions. French wares predominate, particularly southwestern products. Lesser quantities of North Italian, English, New England, and unprovenanced wares were also present. Though the occupants of the house are not known, the household assemblage reflects a middle-class status. This article discusses in detail, dates, and illustrates the coarse earthenwares from this context.

Résumé

Au XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, les faïences communes étaient fabriquées en série pour être exportées dans les colonies; ce qui explique le grand nombre d'artifacts en céramique trouvés sur les chantiers de fouilles. Ces articles, en plus d'être de bons indicateurs chronologiques pour l'ar-chéologue, fournissent des données sociales et économiques sur les habitants et la société en général, et révèlent ou confirment l'existence de relations commerciales. Cet article étudie les faïences communes d'une époque bien définie, trouvées dans une maison située non loin de la forteresse de Louisbourg.

Les artifacts examinés remontent à environ 1745, époque de la première invasion de la colonie par l'Angleterre et la Nouvelle-Angleterre. Les pièces représentent une collection intacte et relativement importante d'objets, aux genres, aux formes/fonctions et aux attributions variées. Comme on peut s'y attendre, la poterie française prédomine, surtout celle du sud-ouest du pays. On y trouve aussi, mais en quantité moindre, des produits du nord de l'Italie, de l'Angleterre, de la Nouvelle-Angleterre et d'autres endroits non identifiés. Bien que l'on ne sache pas exactement qui étaient les occupants de la maison, la nature des articles révèle qu'ils appartenaient à la classe moyenne. L'auteur examine en détail les faïences communes et leur assigne une date compte tenu de ces données.

1 Under the terms of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht the French established a colony on the eastern tip of Cape Breton Island, then called Île Royale. The fortified town named Louisbourg developed into one of the largest mercantile centres on the continent. In 1745 New England and English forces captured the town. After deporting most of the French inhabitants to France, the English remained in occupation for four years. As a result of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 the fortress was restored to France. Ten years later, when France and Great Britain were once more at war, English troops besieged and retook Louisbourg, again expelling the colonists. Fearing the fortress's possible return to the French, the British destroyed the fortifications. In consequence properties were abandoned with the remaining inhabitants shifting to another part of the harbour. By the 1770s the town had gone into a decline and it remained deserted for two centuries.

2 Louisbourg had an active import trade throughout its fifty-five-year existence. Almost everything had to be imported. Trade was transacted with France, her colonies in Quebec and the West Indies, and with the British possessions of Acadia (mainland Nova Scotia) and New England. Ceramics produced in Europe, the Far East, and North America arrived either directly from the manufacturing centre, or indirectly as a result of re-export at the port of origin. British wares, for example, could have been exported to France or New England and then transshipped to Louisbourg. Ceramics of various costs were acquired by Louisbourg's fisherman, artisans, merchants, and civil and military officials. The ceramic material retrieved by archaeology reflects the diversity in country of origin and market values.

3 The group of coarse earthenwares selected for discussion was recovered from a domestic structure on Lot E in Block 2 of the town. Research on primary sources has established the historical background of the site (Dunn 1978a).

Historical Synopsis of Lot E, Block 2

4 In 1722 Dominique Detcheverry, a blacksmith, contracted with Joseph Dugas, a carpenter, to build a duplex on his Lot E property. In exchange for its construction, Dugas received half the house, the land on which it stood, and a small area of the yard. In 1728 Dugas purchased the remainder of Lot E and converted the duplex into a one-family residence.

5 Dugas died of smallpox during the epidemic in 1733. After his death an inventory of the contents of the house was taken by civil officials. The furnishings listed reflect a modest standard of living. No silver was mentioned, and much was described as worn or in poor condition. Ceramic and glass items were not included. Dugas's widow and five children continued to reside in the house for two years. In 1736 the widow remarried, to Charles de Saint-Etienne de La Tour, a widower, whose social and economic status seems to have been higher than Dugas's. If the Dugas-La Tour family lived in the Lot E house from 1736 to 1745, a household of eight (parents and six children) has been suggested (Krause 1975). The site archaeologist has assumed that the couple and three to five children occupied the house at the time (Council 1975, 64). The size of the house and the large amount of ceramics found could have accommodated a family of either size.

6 During the New England occupation, Lot E was part of the property occupied by the English governor. Documentary evidence indicates that the widow Dugas and La Tour may have died in France sometime during this period. Dugas's heirs, however, are recorded as still owning the property in 1749 when the colonists returned to Louisbourg. In the second French period, Lot E was annexed to the adjoining property of the chief French civil administrator, and the building made an extension of the stables. During the second English occupation the lot was part of the governor's residence, with the structure functioning as either a stable or storehouse until the garrison withdrew in 1767. The next year it is reported in a rundown condition.

Archaeological Background

7 Lot E underwent preliminary archaeological investigations in 1959, 1968, and 1970. The site was excavated most extensively in 1975 by R. Bruce Council. An analysis of the material from the site, subdivided according to artifact class, was undertaken, and a report on the glassware has been published (Smith 1981). The ceramics were studied by the author.

8 The scope of the project was restricted to artifacts, both ceramic and glass, from an archaeological layer which in this case was the 1745 siege debris. The field archaeologist believed that the house was destroyed during the siege and rebuilt. The basis for this interpretation was the presence of eight cannon-balls in the siege refuse. Since this was a significant event that provided a datable and a discrete context, the artifactual material from this time was chosen for analysis. The specific date of the context was within the first French period, and the analysis could therefore provide information for architectural reconstruction and furnishing.

9 A detailed report on the tin-glazed earthenwares, stonewares, and Chinese export porcelains from the siege debris is on file with Parks Canada. The coarse earthenwares comprised slightly over a third of the ceramic assemblage. Comparisons vis-à-vis vessel form/function and provenance will be made later in this paper. The analysis of the ceramics does not support the archaeologist's theory that the house was consumed by fire due to bombardment, but does demonstrate that the deposit of artifacts was affected by the siege of 1745. A small percentage of the ceramics showed evidence of burning other than that caused in cooking. The cannon-balls doubtless caused structural damage but not necessarily demolition or conflagration. The house was either abandoned or evacuated as a result of the siege. The large number of restorable objects, their mends, and their distribution pattern indicate a non-random rather than random distribution. Nothing is intrusive and the dates for the objects are compatible with the date of the deposit. The ceramics therefore represent a relatively undisturbed, complete assemblage deposited about 1745.

10 Despite the massive quantity and quality of the ceramic collections at Louisbourg, little has been written or published (Barton 1981; Drakich 1981; Dunton 1971; Fairbanks 1975; Lynch 1969; Marwitt 1967; Palardy 1971). Literature dealing with ordinary historic French period ceramics is scarce, and what has been written is either unpublished, limited in circulation, or is unavailable. Coarse earthenwares are the most common utilitarian ware and predominate on most sites of this period but are often neglected in reports. Current descriptive reports allow us to correct or confirm existing dates. This discussion of the coarse earthenwares contributes information on the contents of a mid-eighteenth-century, French colonial, domestic ceramic assemblage, and to make some general statements on the social and economic status of the owners. The data should provide a basis for comparison with other sites and assemblages of similar social and economic backgrounds.

Methodology

11 Two significant studies by K. Barton (1981) and G. Gusset (1978) have formed the basis of the identification of this group of coarse earthenwares. Dates are based on parallel material excavated from datable European sites and in museum collections. The format adopted here lists the essential features distinguishing each type — fabric, glaze, decoration, vessel forms, date, and attribution. Since most of the objects were wheel-thrown, the quality of manufacture will be noted as well as the few instances of the use of moulds. The material has been divided into broad geographical groups — French, northern Italian, English, Anglo-American, and each group has been subdivided into specific types.

French Imports

Saintonge Wares

12 The most common wares are from the Saintonge region of southwest France. The two types within this group are pink-bodied wares decorated with slip and glaze, or buff-bodied and glazed pieces. Bases are slightly concave and usually fettled. The glaze has been applied carelessly, with frequent splashes, dribbles, and over- and underlapping slip surfaces. The abundance of stick and touch marks -patches of glaze and depressions - on the pots indicates vessels were stacked close together in the kilns; and they were fired in an oxidizing atmosphere. Most of the examples have bases blackened by fire. A good sample of the range of shapes, mostly hollow-ware, shows the wares were used in food and drink preparation, service, consumption, and storage. These wares are found on Canadian archaeological sites dating from the end of the seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century (Gusset 1978). Production of the ware is attributed to the potteries in the village of La Chapelle des Pots near the town of Saintes in the province of Saintonge.

Pink Fabric Slip-Decorated and Glazed Wares

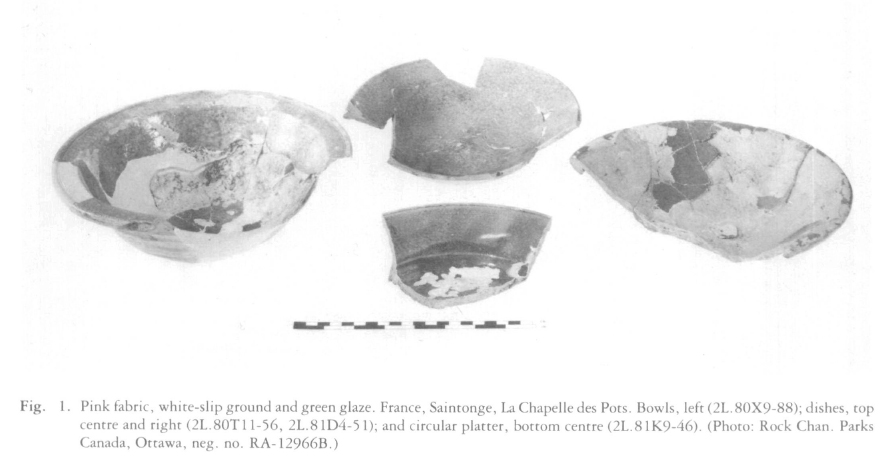

13 The majority of the slip-wares have a pink fabric with a white slip, coloured slip, or oxide motifs and a green copper-oxide or transparent lead glaze. The clear glaze was intended to be colourless but the presence of impurities in it produced a yellow or greenish tinge. Twenty of these slip-decorated sherds are white-slipped and green-glazed and are a type found at all French colonial sites. The slip has been applied by dipping the ware. The interiors of open hollow- and flatwares, such as bowls and plates, are covered with white slip and then glazed with the exteriors left unglazed. The exterior of most closed hollow shapes, such as pitchers and mugs, are covered with white slip and both the interiors and exteriors are usually glazed. Eight of the objects are deep bowls, all similar in form with truncated cone-shaped sides and an everted rolled rim. There is generally one groove, sometimes two, at the edge of the raised rim. The distance between the rim and the groove(s) varies. There were three sizes at Louisbourg — small (rim diameter 23 cm), medium (29 cm), and large (36 cm) (Barton 1981:13-14). Our examples have rim diameters ranging from 28 to 32 centimetres. The most complete bowl is illustrated in fig. 1 left.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 114 A 'dish' is a variant form similar to a bowl but shallower and without a lip. There are three examples, all with folded rims but with two different profiles. Dishes illustrating the two rim forms are shown in figure 1. The rim of the dish in the top middle of the photograph has been smoothed on the outer side imparting a triangular shape. The dish on the right in figure 1 has the exterior rolled part of the rim slightly separate from the body.

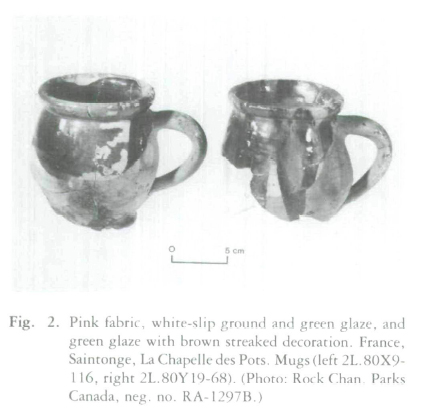

15 Of the French products, only in the Saintonge slip-wares are there drinking vessels. In the white-slipped, green-glazed group there are mugs or single-handled pots. The characteristic shape is a bulging rim, globular body, pedestal-foot base, and a rod or ribbed handle attached below the rim. The mug on the left in figure 2 is the only complete example in this assemblage. This mug was burnt on the base and lower exterior body which may reflect use over a direct fire to heat liquids or cook food. These single-handled pots probably fulfilled a number of functions apart from drinking ware.

16 The single flat-ware piece in this group is a circular platter (fig. 1, bottom centre). It has a deep sloping lip with an incised folded rim.

17 The next largest decorative group within this type consists of objects with the characteristic pink fabric and white slip and which are further embellished with metallic oxides added to the glaze. They exhibit a similar range of functional shapes and physical attributes to that of the preceding group. In figure 2 the piece shown on the left has a white slip and green glaze and vertical brown streaks, due to the addition of iron oxide to the glaze. The remaining objects include a bowl and unidentifiable base or body fragments. The combination of a white slip, brown bloches on the rim, and a clear glaze gives a greenish yellow colour to the bowl.

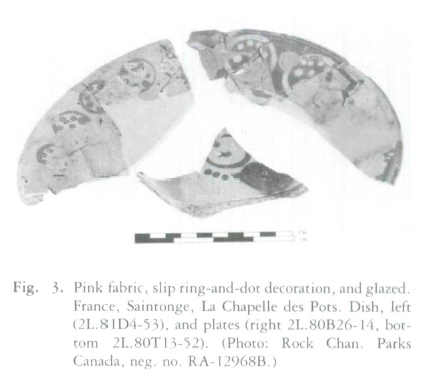

18 The most distinctive within the Saintonge type are the ring-and-dot wares, represented by three objects. The presence or absence of white slip, the colour of the slip in which the motif is painted, the configuration of the circle and dot motif, and the colour of the overlaying clear glaze can produce many different colour combinations. Some of the variations are shown in figure 3. The dish on the kit has a white slip, a series of rings and dots in an orange brown slip around the rim, and a glaze which gives a greenish yellow colour to the piece. On the right in figure 3 is a plate with the motif in white slip. Through the clear glaze the fabric appears orange and the slip yellow. The plate sherd in the centre of the photograph has a white slip with ring and dots in an orange-brown slip. The piece is covered with a greenish yellow glaze. The rings and dots in this decorative group were done free-hand, so the size and the shapes can vary from circular to diamond.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

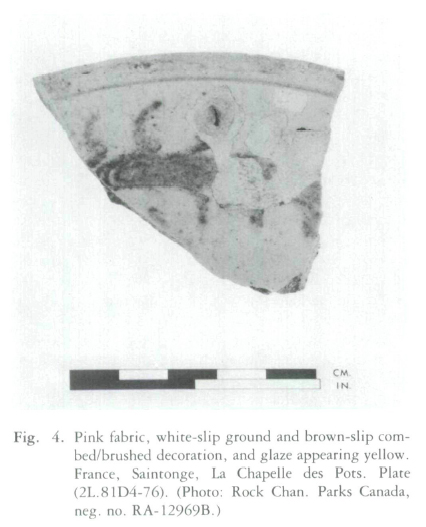

Display large image of Figure 419 The Saintonge slip-wares are also decorated in a motif called "tree" or "moss." A dark red or brown slip is trailed over a slipped surface and then combed and/or brushed, giving a floral appearance. We have two examples of small plates with an incised rim and deep, flat, sloping lips. The more complete specimen has a yellow glaze with additional touches of green glaze on the rim and body (fig. 4).

Buff Fabric Green-Glazed Wares

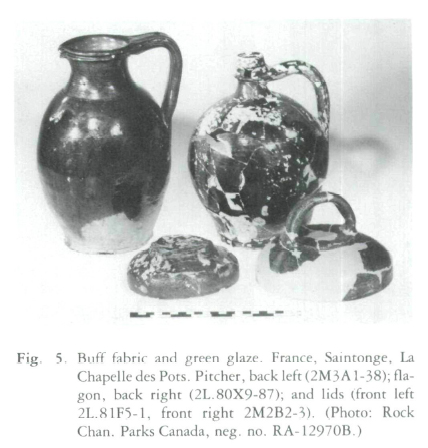

20 This ware has a buff fabric and a dark green glaze. The functional categories, manufacturing techniques, quality, and date range are similar to the preceding type, with only the vessel forms differing. This ware is not as numerous as slip-wares. Figure 5 illustrates some of the shapes. The pitcher on the right was recovered from the French frigate Machault (provenance no. 2M), scuttled on the Restigouche River in 1760. This pitcher is shown here as comparable to the one found in the Louisbourg siege debris. Unfortunately, only the rim and handle remains of the piece from Louisbourg. The pitchers from the Machault have as features a pulled spout, square-sectioned ribbed rims, strap handles attached to the rims, constricted necks, globular bodies, flat bases with flaring foot-rims, and uneven internal and external glazing.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 621 Next to the pitcher in figure 5 is a flagon or bottle. It has a square rim in section, short neck, wide flange below on which is attached a pulled handle, squat globular body, and flat base. A green glaze is on the exterior and part of the interior. A flagon recovered from the Machault is taller and with a more elongated body than our flagon.

22 The remaining objects in figure 5 are lids. The smaller one missing the handle (on the left) is from the ca. 1745 layer. The other is from the Machault and illustrates the shape. The larger lid was used on a tripod cooking pot (Barton 1977, fig. 5). The two lids were made by taking an upside-down pedestal-base bowl and adding a strap handle to the base.

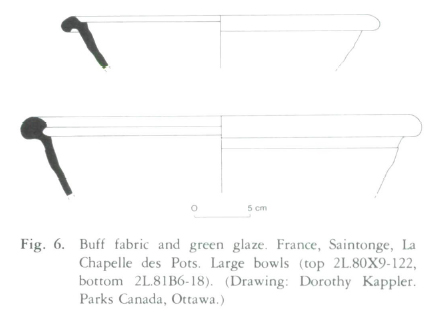

23 The two buff fabric and green-glazed bowls shown in figure 6 have distinctive rim forms unlike other similar wares at Louisbourg (Barton 1981, fig. 9). The top bowl has an everted rim and interior ledge, possibly for a lid, and part of the base with a foot-rim, a glazed interior, and an unglazed exterior.

Buff to Light Red Fabric, Unglazed or Clear-Glazed Wares

24 Within this group the colour of the fabric varies from buff to light red, and the texture from smooth to rough. Vessels are unglazed or partly glazed, appearing yellow or orange in colour. Recorded forms are limited to cooking pots, lids, and large storage jars. The provenance is presumed to be southwest France since large quantities of the cooking pots were found at Port Bertrand in Charente-Maritime (Barton 1981, 21). Chapelot (1978, 112) attributes them to the Mediterranean area. This ware is found in Canada from the first half of the eighteenth century to the 1760s (Gusset 1978).

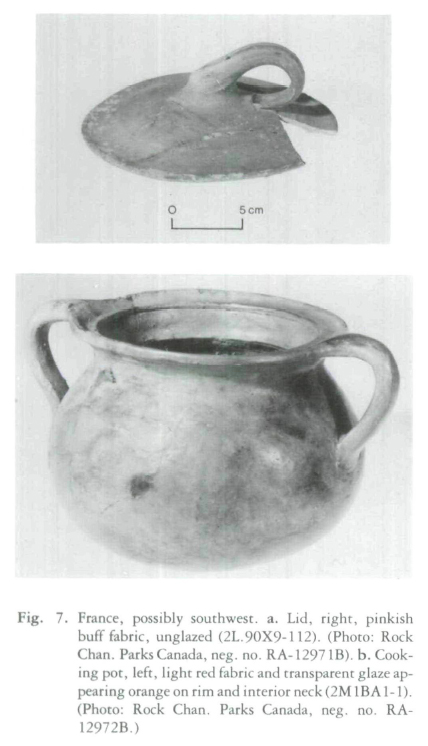

25 The single complete example of an unglazed lid is illustrated in figure 7a. It has a buff-coloured fabric, a slightly everted basal rim, and shallow sides with a handle fastened onto the centre of the dome and looped under. Lids in our assemblage seem to be an interrrelated group sharing a common origin. Though their fabric colour and texture are different to that of the cooking pots, the differences can probably be attributed to firing conditions, placement in the kiln, and not the source of production.

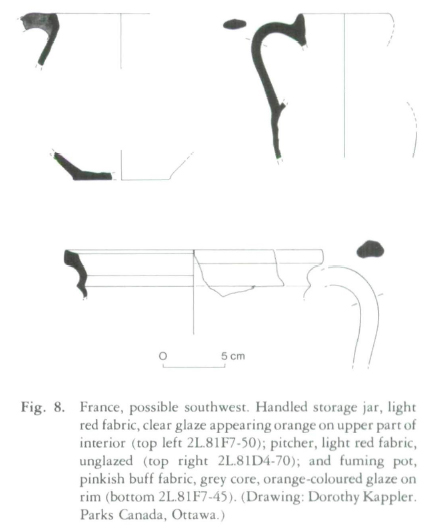

26 Two other objects could be grouped with this ware because of overall appearance. One is a small pitcher (fig. 8, top right) with a pinkish buff fabric, heavily tilled on the interior, with the handle attached below the rim. The second object is a constricted hollow shape such as a storage jar (vide Barton 1981, fig. 9, no. 15). The fabric is a pale red colour with many small white inclusions giving a granular texture.

27 Glazed wares include three cooking pots with light red fabric and clear glaze, giving an orange colour to the finished piece. These pots had the traditional shape of a constricted neck, globular body with two handles, and round bottom (see fig. 7).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 828 An unusual object in the assemblage, drawn at the bottom of figure 8, has a shape similar to the cooking pots but is a unique piece in the Louisbourg collection. Only a rim and a handle fragment are present. The fabric is pinkish buff with a grey core and there is an orange-coloured glaze on the interior rim. A horizontal slit in the body just below the shoulder appears to be deliberate because it was made prior to glazing and firing. This slit suggests the piece was a fuming pot, which would have vents in the upper part of the body to allow scented fumes to escape the covered receptacle.

29 The object shown in figure 8, top right, is a storage jar or a small cooking pot. The fabric is light red with small white inclusions. An orange-coloured glaze has been applied on the rim and the interior upper body.

White/Buff Fabric, Slip- or Oxide-Decorated, and Glazed Wares

30 This ware has a fabric varying from white to buff colour. The pieces have turned rims with smoothed surfaces, fettled bases, and fairly carefully applied glaze. The wares are likely the products of the potting community at Martincamp (Chapelot 1979, 110), which is between Dieppe and Beauvais in the province of Normandy. The Beauvaisis area in the north, like Saintonge in the southwest, was an area known for its potting industry. These wares were manufactured throughout the eighteenth century; the slip-ware can be dated even earlier to the seventeenth century.

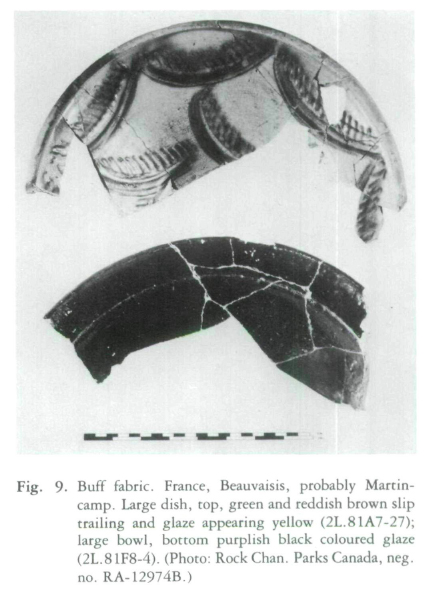

31 Decoration can be divided into three categories: slip trailing, oxide-stained glaze, and oxide-sprinkled glaze. The first group is represented by a dish (fig. 9, top) with a typical hammer-head rim form, truncated cone-shaped sides and flat base. Its decoration consists of slip-trailed arcs and dashes alternating in green and reddish brown. The brown slip was trailed first and then the green. The green lines seem to have been made by trailing white slip and then covering with a liquid copper oxide solution. A clear lead glaze was placed over the slip. The pattern probably would have had a stylized floral design. This type of decoration can also occur on plates and bowls at Louisbourg. According to Chapelot (1978, 110) identical slip-wares were produced at Sorrus, north of Martincamp.

32 The second decorative style has a lustrous dark purple glaze applied on the interior. The colourant is hematite, which was sprinkled on the transparent glaze. Manganese oxide has also been suggested as the colouring agent. Two objects of this type were found: both are large bowls of the same size and shape. The more complete one is illustrated at the bottom of figure 9. It has a horizontal, slightly concave, everted rim and convex sides.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

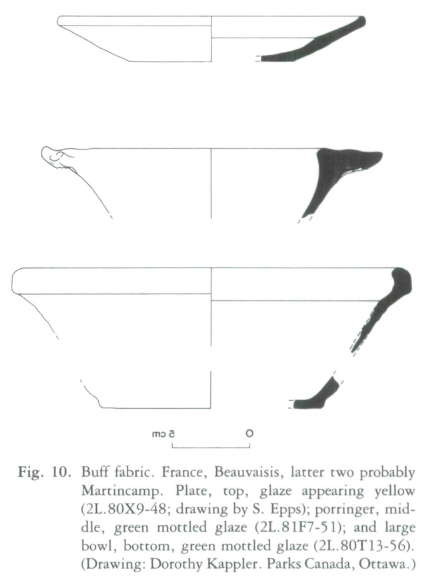

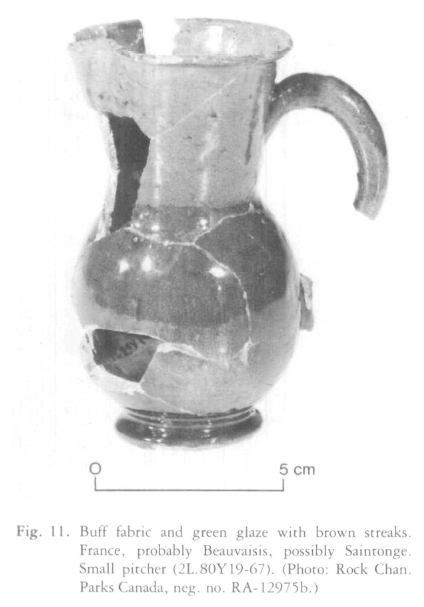

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1133 The third group has powdered copper oxide sprinkled on the glaze covering the interior and probably the entire exterior. The oxide gave a green mottled effect when applied over a yellowish colour fabric. The hollow-ware objects have this treatment (fig. 10). A porringer is in the middle of the drawing. At the bottom is illustrated a large bowl with a thick upturned rim. At the top of figure 10 is a small plate covered on the interior and exterior with a clear yellow glaze with a greenish tinge. Figure 11 shows a small pitcher with a green coloured glaze and brown iron oxide on top to produce a streaky appearance. Both pieces may be Saintonge or Beauvaisis ware.

Red Fabric, Slip-Decorated, and Brown-Glazed Wares

34 This ware type has a fine red fabric with a soft texture. Decoration comes in various coloured slip and glaze combinations and techniques; there is a wide range of shapes. The principal decoration, a whorl pattern, is so characteristic and familiar on North American French colonial sites that this ware type is readily recognizable. Most of our sherds seem to have a white slip applied over a red slip. Sometimes splotches of green glaze are on top of the white slip. Vessels are wheel-thrown and finished on the interior but not on the exterior. This ware was probably made in the south of France in the Rhône Valley or Provence area (Gusset 1978). It is found on North American sites that date to the first half of the eighteenth century (Chapelot 1978, 112). From a different context on the Lot E site is a complete deep bowl that is spalled, and clearly shows the shape and size of the vessel. This gives a better impression of the decoration. The characteristic shape for these bowls is a square rim in section, truncated cone-shaped sides, and slightly concave base. All three have a red slip ground with the whorl pattern.

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 1235 Small bowls have inverted rims, convex sides, and flat bases with flaring foot-rims. All but one have the typical whorl pattern (fig. 12, top). The base shard at the bottom of figure 12 has the circle-of-dots motif.

Red Fabric, White-Slip Ground, Green and Purple Decorated, and Clear Colourless Glazed Wares

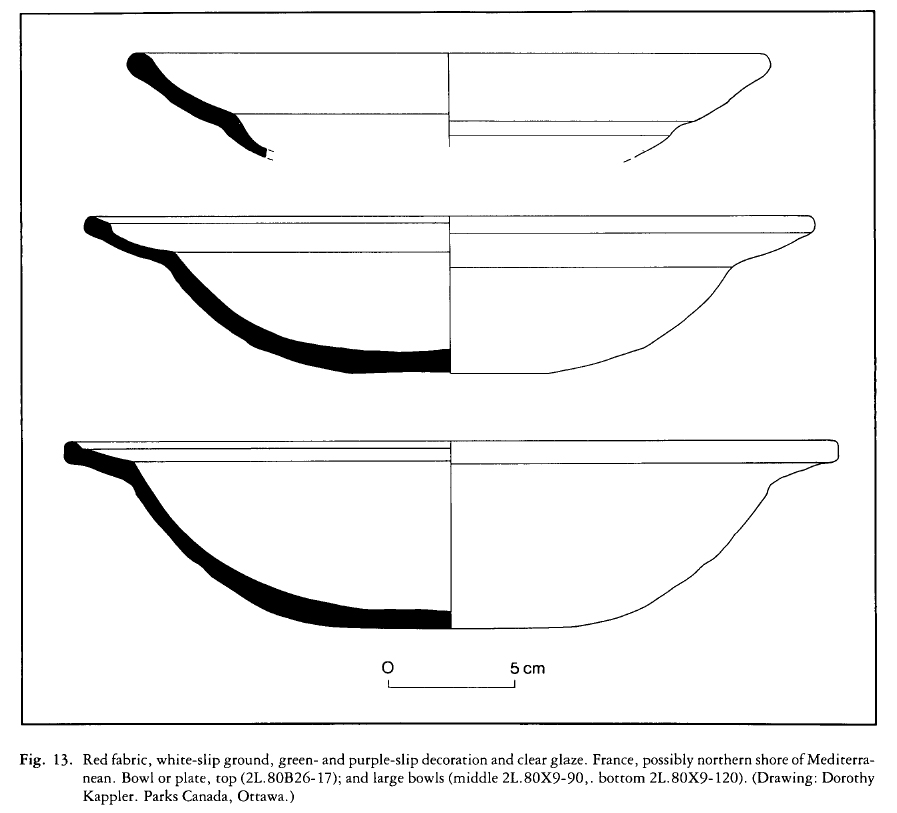

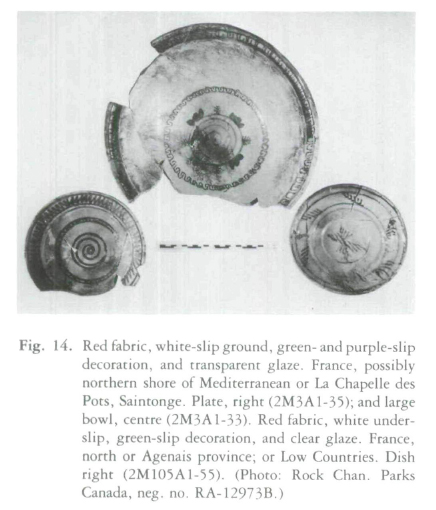

36 This ware has a coarse red fabric covered with a white slip on the interior. On the surface of the white slip is painted or trailed green (copper oxide) and purple (iron, or perhaps manganese, oxide) markings. Decoration is usually composed of geometric motifs, such as zigzag lines, spirals, and stylized floral elements, in various designs, combinations, and styles. A clear colourless lead glaze has been applied which appears yellowish over a white slip. The wares have been thrown on the wheel with the interiors smoothed and the exteriors and bases turned. The recorded range of shapes consists of bowls and shallow plates. Barton (1981, 37-38) has suggested, on the basis of similarity of forms, the northern Mediterranean coast as the manufacturing area for this ware. Schurman (1978, pers. com.), on the other hand, thought La Chapelle des Pots in Saintonge the likely source. Identical material has been excavated from Canadian site contexts dating from the second quarter to the third quarter of the eighteenth century (Gusset 1978).

37 The two bowls in figure 13 (middle and bottom) have slight variations in rim form and size. Common traits are raised bead rims, sloping lips, convex sides, and flat bases. The incomplete bowl at the top of figure 13 has a white slip. The glaze has not survived on the interior. Overlapping the rim on the exterior is a light brown glaze. The extant form could be a bowl shape (Barton 1977, fig. 10); however, it is also similar to the plates occurring in the preceding ware type (Barton 1981, fig. 14, no. 10). Its provenance is southern France, possibly the Rhône Valley.

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13Red Fabric, White-Slip Ground, Green and/or Purple Decorated and Transparent Colourless Glazed Wares

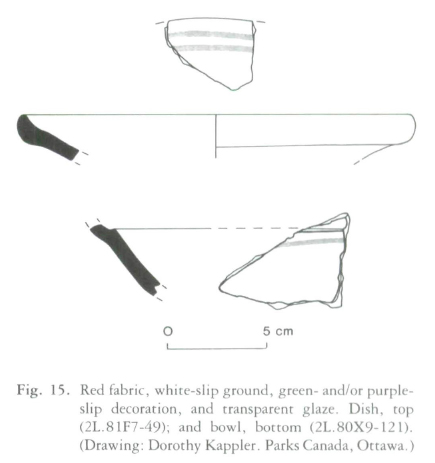

38 These vessels have a red fabric and an interior washed with white slip. On the white slip are geometric motifs, consisting principally of lines — circular, diagonal, curved, or crossing each other (trellis pattern) — which have been slip trailed or painted on in green and/or purple colours (fig. 14). A transparent, colourless, lead glaze appearing yellow covers the slip decoration. Functional shapes for this ware type are bowls and dishes. Provenance is uncertain but similarity of forms with Beauvaisis products suggests that these wares were made in either northern France, with the Low Countries a possibility (Barton 1981, 34), or the southwestern province of Agenais (Chapelot 1978, 110).

39 In this ware type there are two objects and though fragmentary they represent the typical shapes found at Louisbourg. At the top of figure 15 is a dish and below is a body sherd of a bowl. The shape of the latter would have resembled the bowl illustrated by Barton (1981, fig. 23, no. 1), that is, a wide, sloping, concave brim, sharp brink, and convex sides. For both Barton's and our example the bases are not extant.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14Pink Buff Fabric and Clear-Glazed Wares

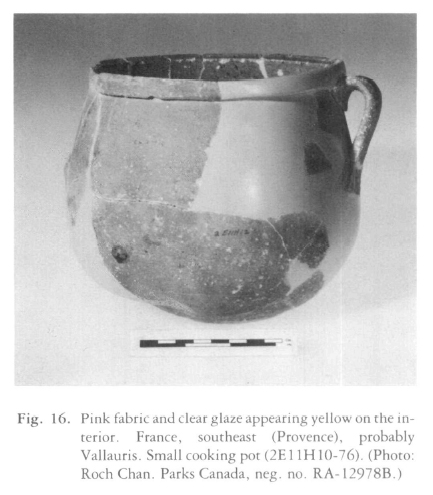

40 The fabric can vary in colour from pink to buff, from vessel to vessel and on the same vessel. Interiors have a lead glaze, but the impurities in the glaze give a yellow orange, or green colour to the vessel. Exterior unglazed surfaces have been smoothed but on the interior potting rings can be seen under the glaze. The glaze tends to spill over the rim with the odd splash on the exterior. This ware type-was used as cooking pots, skillets, bowls, pitchers.

41 These wares came from Vallauris, a major potting centre in Provence in southeastern France where production evidently extended from the seventeenth century until recent times (Chapelot 1978, 111). The standard cooking pot shape for this ware has a folded, square rim in section, globular body, round bottom, and two strap handles attached below the rim (fig. 16a). The illustrated example was recovered from a French occupation context (1751-55) at Fort Beauséjour, New Brunswick (provenance no. 2E). Pitchers are relatively small in size and have a uniform shape with a pulled spout, flaring neck constricted at the shoulder, globular body tapering downward, and flat base (vide Batton 1981, fig. 18, no. 6). An incomplete example was recovered from the layer being studied.

Miscellaneous Wares

42 Two objects of French origin were not classified. One is a complete small lid with a raised semi-circle finial and vertical flange. It has a red fabric and dark brown glaze; the glaze on the underside has been wiped. The second object is a large thick-walled body sherd of pink fabric. The interior is slipped in white and covered with a yellow glaze. The exterior is unglazed. The only forms produced in this ware type are small storage jars, the shape being a truncated conical body, flat base, and lug handles. They are thought to be sugar or grape containers. Possible sources are Cannes or Biot (beside Vallauris), both in Provence (Gusset 1978).

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15North Italian Imports

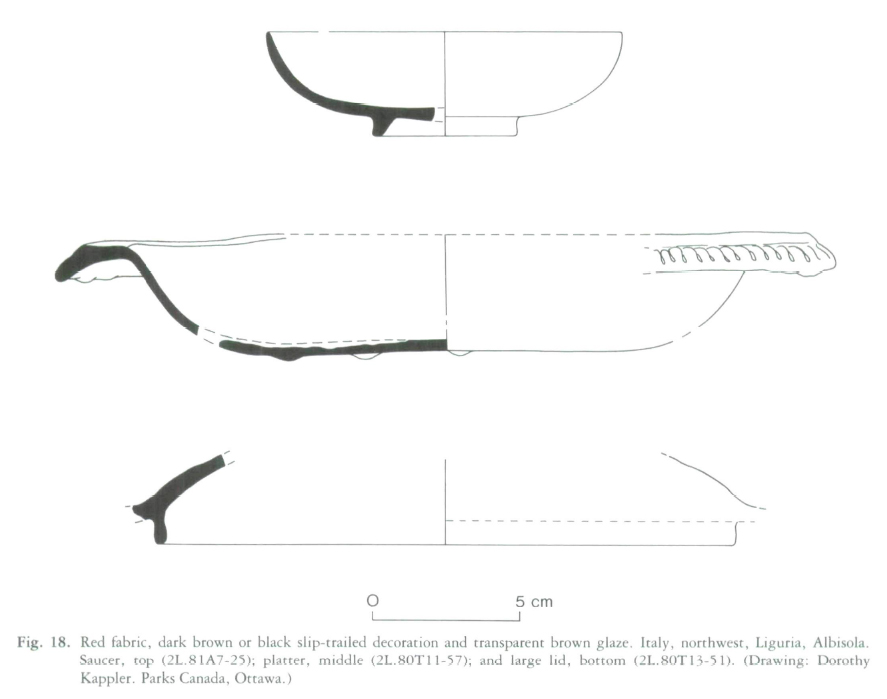

Red Fabric, Dark Brown or Black Slip-Trailed Decorated, and Clear Brown-Glazed Wares

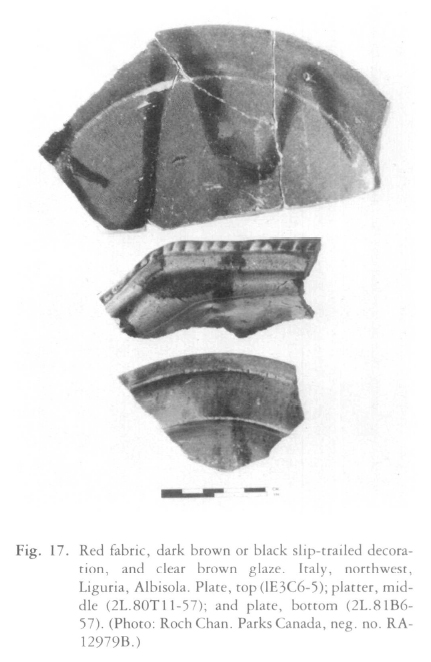

43 This type is the most refined of the coarse earthenwares. The fabric is red with large numbers of fine white inclusions. The decoration consists of random wavy dark lines of brown- or black-coloured slip. A brown, manganese oxide, lead-based glaze, in light or dark shades, was then applied covering the entire vessel (fig. 17). A large assortment of wares for the table was produced — plates, saucers, bowls, porringers, tureens with lids, coffee pots, mugs, and jars with handles.

44 The origin of this ware is the town of Albisola, located west of Genoa, near Savonna, in Liguria, northern Italy (Barton 1981, 46-47). This ware type was extremely popular, so that by the beginning of the nineteenth century it is found in large quantities along the coasts of southern France and northern Italy (Chapelot 1978, 111). It is found at all Canadian French historic sites.

45 The nine objects recovered from the siege refuse included four plates, a saucer, and platter. The plates were thrown on mould and have the same general form — flat angled lip, shallow sloping sides, and flat bases. The plate at the top of figure 17 is from Fort Gaspereau, New Brunswick (provenance no. 1E). The plate in figure 17, bottom, has a lip that is slightly concave with a ridge near the rim. The piece is decorated with a dark brown slip. The saucer in figure 18, top, has shallow convex sides and a vertical foot-ring. It has black slip so indistinct that it blends in with the colour of the glaze. The platter in the middle of figure 18 has an everted rim with a moulded reed design on the border (for detail see fig. 17, middle); and at the edge of the flat base are three drops of glaze arranged in a circular pattern. Hollow-wares are represented by a cup, a lid, and an unidentifiable fragment.

English Imports

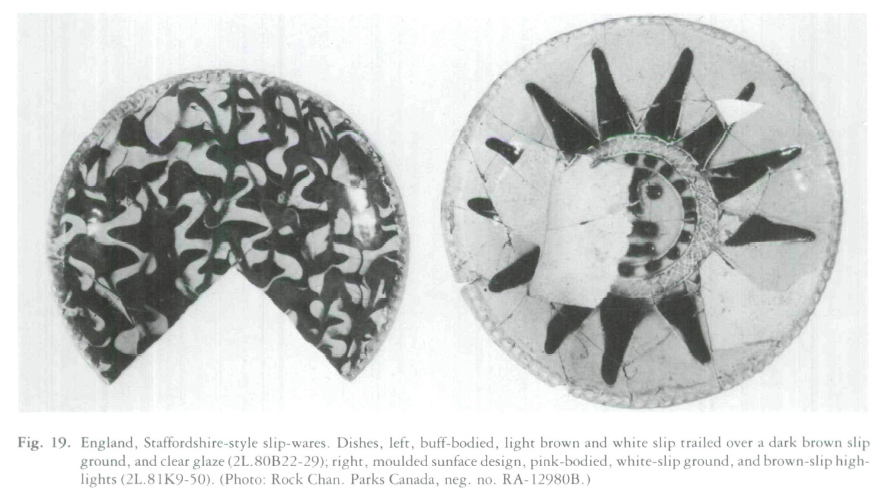

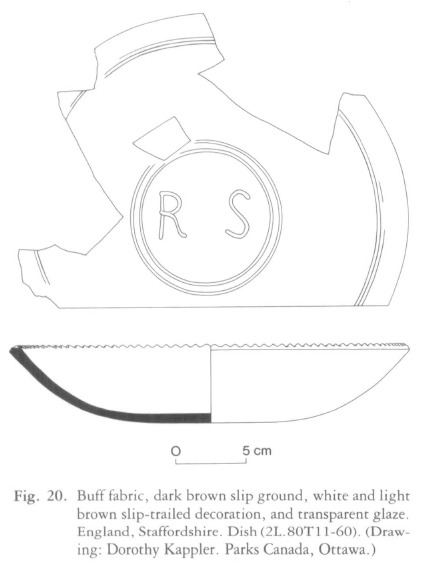

Pink or Buff Fabric, Slip Decoration, and Clear Glaze — Staffordshire Style Wares

46 The various potteries in Staffordshire produced large quantities of slip-decorated wares from the late seventeenth to the end of the eighteenth century. This ware is commonly found in North American deposits dated to the eighteenth century.

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16 Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17 Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18 Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19 Display large image of Figure 20

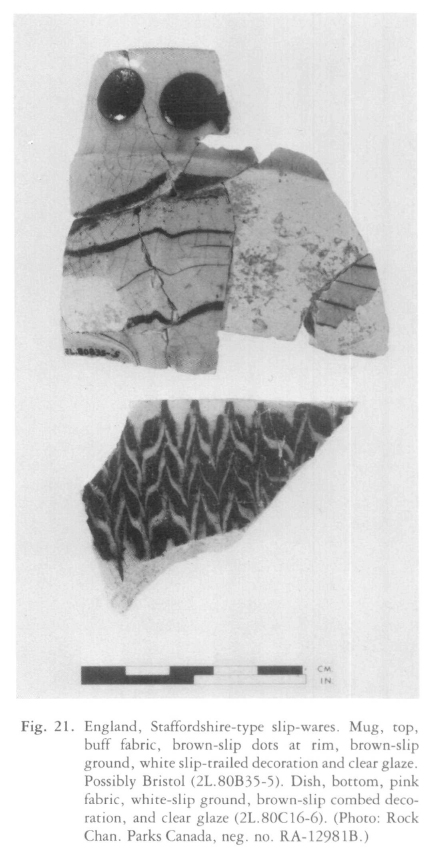

Display large image of Figure 2047 Slip-ware shards recovered from the debris have buff or pink body and various styles of trailed slip decoration of different colours. A transparent lead glaze on top of the slip gives a yellow tint to the wares. The flatwares are all dishes with denticulated rims, shallow sloping sides, and rounded flat bases. The dish shown in figure 19, left, has its interior with dark brown slip, over which has been trailed white and light brown slips. The dish in figure 19, right, has the identical slip pattern but with an additional raised decoration consisting of concentric bands both around the rim and base, and the letters R S within the inner rings (fig. 20). These initials may refer to one of the numerous Simpson family potters.

48 The last flat-ware piece, a pink-bodied base shard, has combed decoration (fig. 21, bottom), made by trailing parallel lines of brown slip over a white-slip surface and then dragging a toothed device through the slips in two directions. This process draws the slips into one another to produce a parallel series of sawtoothed lines with alternating opposite points. A yellow glaze covers the decoration. Staffordshire is the more likely place of origin (Davey 1979, pers. com.) for this piece.

Display large image of Figure 21

Display large image of Figure 2149 Shard from a hollow-ware form (fig. 2 1 , top) with a slightly everted rim, straight neck, and ridge at the point where it joins the globular body, may have been from a posset pot that had two handles. The exterior of the piece is decorated with a horizontal row of dark brown slip dots near the rim edge and slip trailing around the body.

Anglo-American Imports

Miscellaneous British Colonial New England Wares

50 Anglo-American wares are poorly represented since sherds comprising these wares are few and small. Identification of specific ware types and shapes proved impossible; however, these wares are attributed to New England potteries.

Unprovenanced Ware

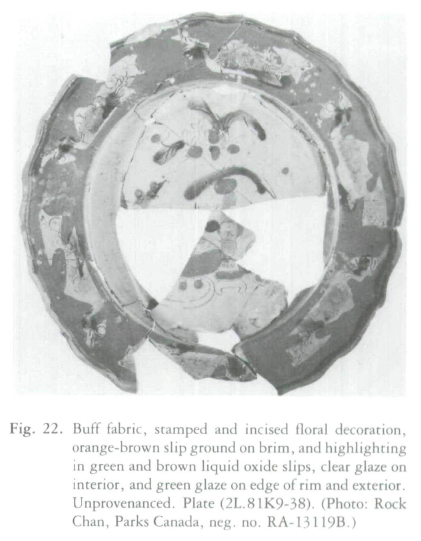

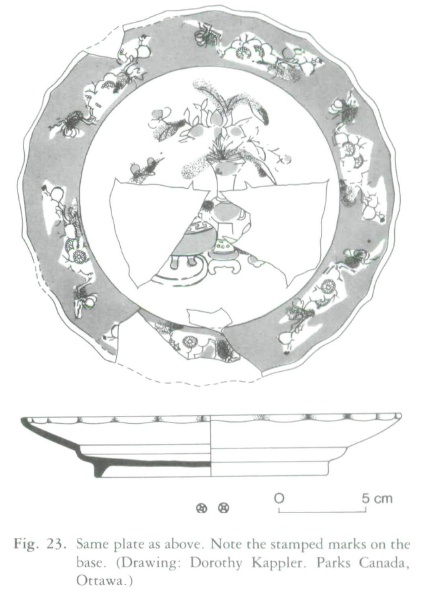

51 This group is represented by a single ware and a single form, the origin and date of which is unknown. Three identical plates were recovered. The plate in figure 22 has a refined white clay fabric. The piece has a scalloped flanged rim, a sloping flat lip, very shallow sides, and a vertical foot-ring. The decoration combines a number of features. On the surface a floral design has been stamped and incised. The lip has six reserved areas with decoration of flowering sprays. The decoration on the interior of the base is a vase with flowers upon a stool. Orange-brown coloured slip frames the reserve panels, and the stamped or incised design has been touched up with green and brown liquid oxide slips. The interior has been coated with a thin clear glaze, giving a pale yellow colour to the piece. A green glaze has been applied to the edge of the rim and to the exterior. At the centre of the unglazed portion of the base are two adjacent, stamped, oval marks that resemble Chinese coins. Such "cash" marks occur on eighteenth-century Chinese export porcelain (Noel Hume 1970, 263, fig. 85).

52 This ware type has been called faïence fine. The closest parallel is the slip-wares produced in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries at Beauvais, France. These Louisbourg plates can be attributed to Beauvais or to some other French pottery inspired by the Beauvaisis examples.

Discussion

53 The number of coarse earthenware objects from the circa 1745 context was 109. Ranking the origin of the wares in descending order, French products comprised 76 per cent of the assemblage, North Italian 8 per cent, and Enlish and New England 6 per cent each, and unprovenanced 3 per cent. Of the 83 French objects, the majority originated from southern areas (86 per cent). Of these, southwestern types predominated (64 per cent) over southeastern (12 per cent) and indeterminate southern types (10 per cent). Northern French types ware present in much lesser amounts (14 per cent), primarily from the Beauvaisis area (12 per cent) with the remainder being in northern types (2 per cent).

54 Locating the source of the ware provides a way to identify the production centres. Research on the origin of wares and shipping documents would improve our understanding of the preferences of the residents of Louisbourg, the supply routes, and trade network.

55 The ceramics found testify to the variety and quantity imported into Louisbourg. France supplied the colony with the greatest range and volume of goods, and in spite of access to other French and European wares by transshipment there apparently was a strong bias on the part of the people of Louisbourg for the products from southwestern France.

Display large image of Figure 22

Display large image of Figure 22 Display large image of Figure 23

Display large image of Figure 2356 All the ceramic ware types fit the circa 1745 date. Because of long or uncertain production dates, coupled with the general lack of datable attributes, no object is significantly early or late for this context. Archaeological finds from closely dated sites in North America such as Louisbourg could provide tighter dates for the production and export of French ceramics.

57 The coarse earthenwares recovered from the siege context of the Lot E house in Block 2 represent but a fraction of the vast array of the ceramics that were imported into Louisbourg. It is hoped that this discussion of the factors differentiating this assemblage — classification, provenance, and functional variation — can provide a basis for the identification and comparison of other excavated material.

* I wish to thank the Fortress of Louisbourg, National Historic Park, Nova Scotia for granting me permission to study this collection of coarse earthenwares, and to the Archaeology Division of Parks Canada, Ottawa, for providing layout space and illustrations. I am grateful to Dorothy Kappler, Rock Chan, and Steve Epps for technical services, to Gérard Gusset and Lynne Sussman for editorial comments, and to Lise Miron for kindly typing my manuscript. For generously discussing details of this article, I also offer my thanks to Douglas Bryce, Peter Davey, Michael Schurman, Ann Smith, Maggie Tugeau, and Virginia Myles. To Dorothy Griffiths whose enthusiasm and standard of ceramic research was inspiring, and to Antony Pacey, a permanent source of assistance and encouragement, I am greatly indebted.