Articles

The Prince Edward Island Pottery, 1880-1898

Abstract

The Prince Edward Island Pottery was established by Oswald Hornsby on the outskirts of Charlottetown in early 1880 and, following its closing in 1898, all structures and buildings were demolished in 1903. During its 18 year operation the pottery produced the greatest range of earthenware forms yet established to any Maritime's pottery, and the only known marked wares. The site of the Prince Edward Island Pottery was excavated by Donald Webster of the Royal Ontario Museum in 1970, ion conjunction with historical research and a survey of its surviving products.

Résumé

La Prince Edward Island Pottery fut fondée au début de 1880 par Oswald Hornsby et poursuivit ses opérations jusqu'en 1898. La manufacture et toutes ses installations situées en banlieue de Charlottetown furent démolies en 1903. Pendant sa période d'activité la compagnie produisit le plus grand nombre de modèles différents de poteries de toutes les Maritimes et les seules pièces à porter l'estampille du fabricant. Cet article veut rendre compte des fouilles archéologiques, menées par Donald Webster du Royal Ontario Museum, qui eurent lieu en 1970 sur le site de l'ancienne manufacture. Parallèlement à ces fouilles, l'auteur a effectué des recherches historiques et dressé un inventaire des produits toujours existants de cette compagnie.

1 The pattern of nineteenth-century Maritimes pottery is evident from existing pieces. Its range is limited to undecorated red earthenwares, types that were in continuous demand and that could compete with British imports in a market the latter could not fully supply. Prior to field work at the site of the Prince Edward Island Pottery, however, no Maritimes pottery had been specifically studied or excavated. The P.E.I. Pottery was excavated because of the range of its products and the known documentary sources and collections.

2 The Prince Edward Island Pottery opened in 1880 on the outskirts of Charlottetown as a corporation to fill local demand for simple household ware, brick, and tile. The business was founded by Frederick W. Hyndman, a native of P.E.I., retired Royal Navy officer and hydrographic surveyor, and then a Charlottetown insurance agent.1 Hyndman was the manager of two operations with Benjamin Godfrey employed to operate the brickyard and Oswald Hornsby as foreman for the pottery. Hornsby had previously managed the Wellington Pottery at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.2 A newspaper article on the June opening of the pottery reported the business as having three buildings, "the largest of which contains the engines for running the brick machine and the bone-mill, the second is used as a pottery, and the third as a dwelling for the foreman and his workmen."

3 The same newspaper described the basic geology of the pottery and brick-works site and its location. "The lot on which the works are situated is eight acres in size. A short distance from the surface is a layer of superior brick clay, from four to six feet deep. Under this is a layer of sand and sandstone, beneath which is a layer of fine red clay, which is used for pottery purposes. The thickness of the latter layer has not yet been discovered, but in digging a well a short distance from the last the same clay was found to be thirty feet thick."3

4 The potter, Oswald Hornsby, was born in Londonderry, Ireland, and came to Nova Scotia in the early 1850s.4 The similarity of some P.E.I, wares to nineteenth-century English earthenware of the Sunderland area suggests that he was acquainted with the industry there before emigration. Hornsby moved to Charlottetown with wife and family in 1879 to supervise construction of the pottery. It was in operation, except for the brick kiln, by the spring of 1880. We cannot determine how well the operation fared during its earlier period, since no financial or sales records have survived. Hyndman advertised his pottery and developed markets in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.5 A newspaper article in early 1883 provided the first indication that the P.E.I. Pottery was not doing well when it noted, "the company have not met the success they anticipated when they started the works in 1880."6 The domestic market was too small to support local manufacturing since inexpensive mass-produced British imports were available at low prices.

5 The P.E.I. Pottery received attention in a newspaper notice on 6 October 1885.

THE P.E. ISLAND POTTERY

The Pottery Company of P.E. Island offer for sale their Pottery Factory and premises, situate in the royalty of Charlottetown, comprising Five Acres of Land, together with a large, well-built Kiln, suitable buildings for manufacturing and storing the ware, and a commodious Warehouse. The Pottery is well equipped with necessary and suitable plant for the manufacture of all kinds of earthenware, and connected by a siding with the railway. The cellar is stocked with prepared clay for manufacture during the winter. The Factory is now in full operation, has a market for all it can manufacture, and its ware is giving good satisfaction. Intending purchasers can inspect the premises.

Liberal terms given.

Messrs. Beer & Goff,

or F.W. Hyndman,

Secretary.

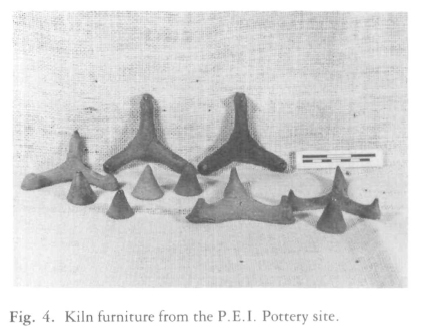

6 No purchasers appeared, and Hyndman leased the pottery to Oswald Hornsby and a partner named Murphy (replacing Beer and Goff), who announced the management change in an advertisement in the Weekly Examiner of 30 July 1886. They also stated: "A New Line of Ware — will be at once manufactured at prices that will defy competitions."8

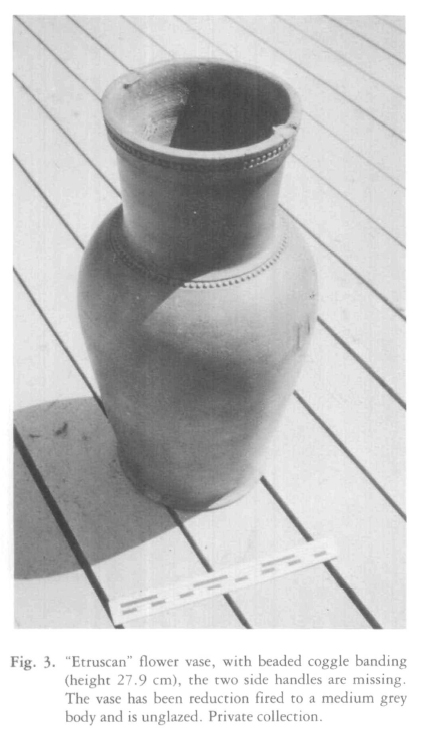

7 A few days later Frederick Hyndman, perhaps at odds with Hornsby and Murphy, advertised the sale of unsold wares as follows:

8 No further descriptions of the pottery are reported until an 1890 article on the P.E.I. Provincial Exhibition described the business and its products:

9 One resident of Charlottetown, William Casford, in 1970 still remembered the Pottery well from the late 1890s. The son of John Casford, a former employee, William, when young, spent a lot of time at the factory. Casford recalled that about 1895 the Pottery complex included four structures along Pottery Lane, an abandoned roadway. Near railroad tracks stood the kiln, a round beehive-domed, up-draft structure about thirty feet in diameter, built of brick brought in from a brickworks at Southport. This kiln had six fire-boxes equally spaced around its circumference, and used four-foot hardwood logs as fuel. The complete firing process took three days. There were also six "try-holes" for inspection of pottery during firing. Near the kiln were the pottery building, and a shed for storing clay. Finally, furthest from the railroad tracks was a two-storey, flat-roofed warehouse for storing unsold stock. Casford remembered that these buildings were heated by "Red Cloud" stoves.

10 According to William Casford, clay was dug at Inker-man, P.E.I. When this supply was exhausted, shoreline clay was collected at Rocky Point and delivered by horse and wagon, by way of the Rocky Point-Charlottetown ferry. At the Pottery the clay was processed in a large horse-powered pug mill. Then it was screened and poured into pits in the ground to reharden. Finally, it was worked through an extrusion press, also horse-powered, and the blocks cut into four- and six-inch square or rectangular blocks. These were stored until needed. According to Casford's recollections, the pottery was fired only once, but unglazed slip-coated biscuit was excavated, suggesting that wares were separately biscuit and glost fired.

11 The products were sold throughout Prince Edward Island and shipped to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and possibly the Gaspé and Newfoundland. Wares were packed with straw in heavy four-foot square crates made of woven sticks.

12 Oswald Hornsby left the pottery in 1896 or 1897 to establish a book and stationery shop in Charlottetown. His son Frank took over the operation but soon stopped producing container wares and ornamental pottery, and made unglazed chimney-pots, some of which can still be seen in Charlottetown.

13 The pottery closed in late 1897 or early 1898. An advertisement of the auction of the land, buildings, and the kiln for its brick appeared in the Daily Examiner of 28 April 1898.11 Frederick Hyndman and his brother Charles still owned the land; the Hornsbys having had a leasehold.12 After the auction, the land was transferred to Sir Louis H. Davies, Hyndman's cousin, the then federal minister of marine and fisheries. The conveyance stipulated that the buildings be removed by 10 June 1898.13

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 314 The Federal Department of Agriculture acquired the land in 1902 or 1903 to form part of what is now the Federal Agricultural Research Station.14 The pottery warehouse was moved a short distance to an existing farm, which later became the nucleus of the research station, and thus still survives.

15 The site of the P.E.I. Pottery is a plowed field, bounded on the west by the Canadian National railroad embankment and tracks running through the research station, and on the north by the abandoned Pottery Lane (fig. 1). Essentially a narrow strip of land some 400 feet long, the site extends some 75 feet south from the abandoned road. The land slopes gradually downhill from east to west and, except for exposed sherds on the surface, there is no indication of any previous pottery activity.

16 The topsoil at the site consisted of a red brown loam, 18 to 24 inches deep. The upper foot of this layer had been plowed and cleared of stone and sherds, so that its texture is fine. The subsoil is a hard, compact clay, also red brown in colour.

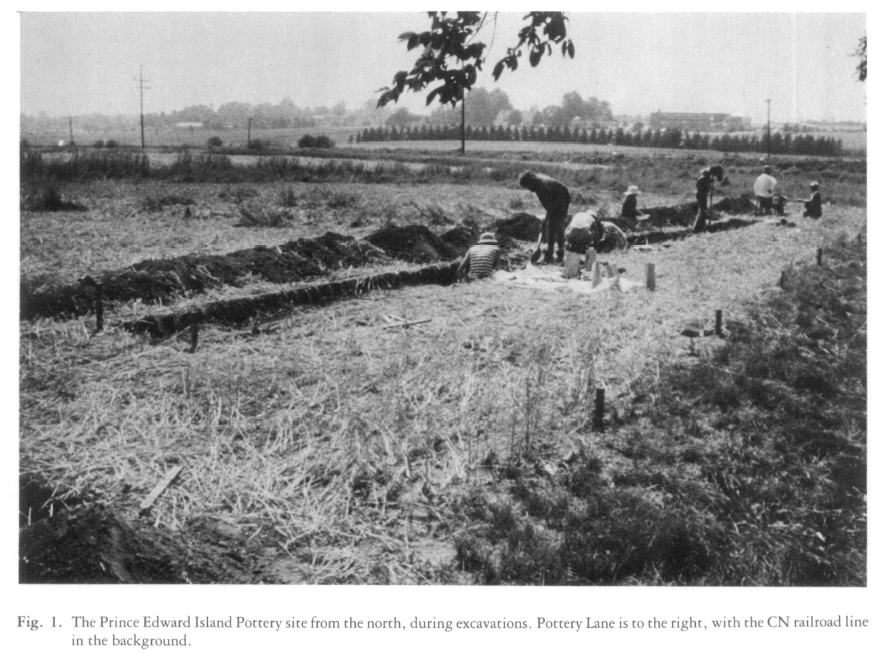

17 Excavations at the P.E.I. Pottery site were carried out for ten days in August 1970. We limited work to a search for waster dumps and evidence of the location of buildings. A three-foot survey trench was laid out from the eastern limit of the pottery grounds to the CN tracks, parallel to Pottery Lane, and forty feet to the south. Begun near the higher eastern end, this trench was dug CO the clay level. In only one area, 300 to 330 feet east of the railroad tracks, was a waster found, and this was below the plow zone but above the clay subsoil. Waster sherds included parts of "rustic" tobacco jars (fig. 2), known to have been in production in 1880, and pieces of "Etruscan" vases (fig. 3), mentioned in 1882.15 Since waster pottery, except for the earliest level, had been removed, we can conclude the area excavated represented the wares produced in the early 1880s. Kiln furniture, found in quantity, consisted of two types of stilts and small wedges.

18 The P.E.I. Pottery, unlike those in Ontario, used standard ceramic stilts as separators. Three-branched but flat-backed stilts served for smaller pots, probably with flat sides to exterior bases, and pins to interior glazed surfaces. Conical single-pin stilts separated larger vessels, in the same manner (fig. 4). Placement of the conical stilts required the upside-down stacking of pieces. Saggars were used for plates, saucers, and small pieces. The saggars had openings for the circulation of heat.

19 Sherds recovered indicate that glazed pottery had been fired twice: first, biscuit firing at a high temperature, and then the glost firing at a lower tempetarure. Approximately 30 per cent of sherds recovered were biscuit fired and similar to others which were glazed. Approximately 25 per cent of sherds were of unglazed bisque flower pots, saucers, or jardinières. The remaining 45 per cent of the sherds were of glazed and finished pieces.

20 A newspaper article mentioned that the pottery produced "about 480½-gallon pots per day and about twice as many smaller ones."16 We can thus reasonably estimate a production of 7,000 to 10,000 vessels a month.

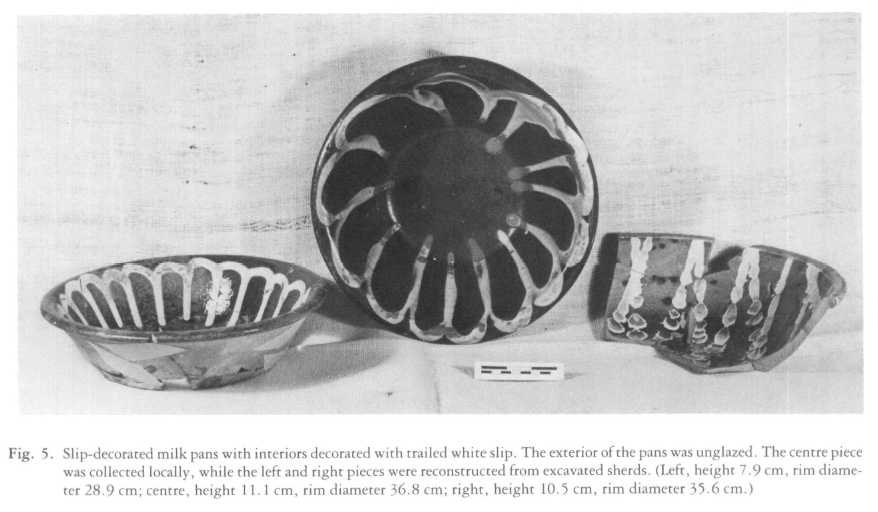

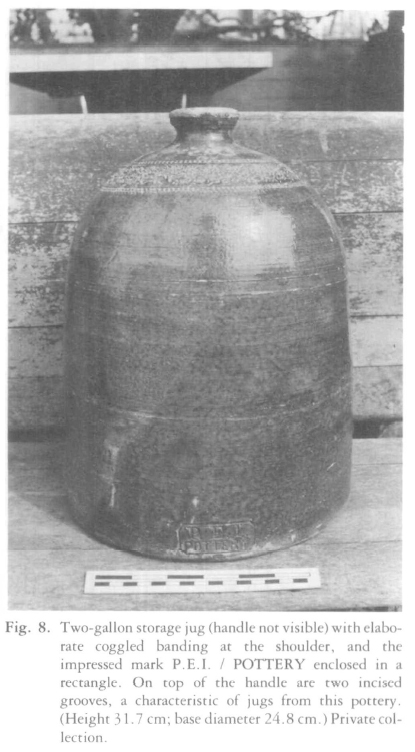

21 With the exception of two uncommon forms, all P.E.I. Pottery products excavated or observed were wheel-turned and produced entirely by hand. Portions of the "Rustic" tobacco boxes (fig. 2) were slip-cast in moulds and combined with hand made components. The standard finish, judging from sherds and existing pieces, was a transparent lead glaze. Copper oxide was used to give a green colour and, iron oxide was used for a yellow colour. The pottery used a white slip, mixed to a liquid consistency, as a liner for the interiors of jars and large bowls or for a dripped loop decoration on milk bowls (fig. 5). Many of the pottery's products, such as undecorated white-slip-lined milk bowls, were typical of wares produced generally in the Maritimes. There are decorative characteristics, however, which are distinctive of it, including coggle-wheel produced banding, and curved banding. The incising of lines on handles of jugs is also unique to this pottery.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

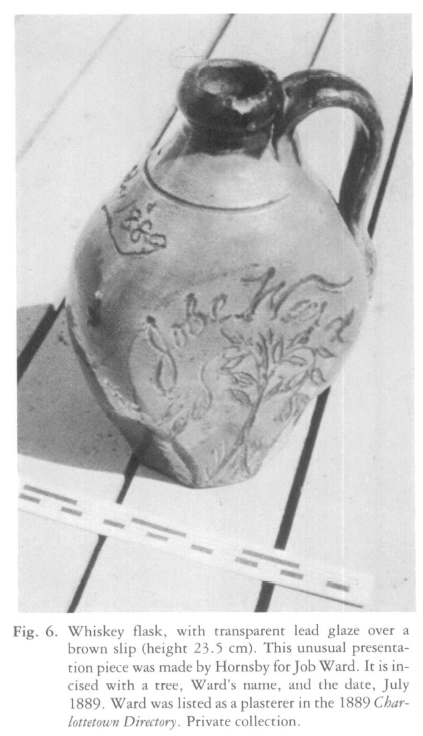

Display large image of Figure 922 The majority of wares produced at the pottery were utilitarian containers and flower pots. There are, though, a few examples of gift pieces made by Hornsby during his time at the plant: the Ward flask (fig. 6) is one example.

23 The Prince Edward Island Pottery, like other earthenware potteries in Canada, could continue only as long as there was a demand for the limited range of wares they produced. Examples of the products of this pottery are shown in figures 7-9.

24 The P.E.I. Pottery project depended on the offerings and aid of a number of people, to whom I am indebted for making the investigation possible and successful. Lloyd MacLeod and George Ayers of the Department of Agriculture Research Station authorized the excavation readily and with great interest. Douglas Boylan, provincial archivist, aided both our planning and documentary research. Catherine Hennessey of Charlottetown let us photograph her collection, led us to other sources, and made available her own file of research notes on the pottery. Mr. and Mrs. Harry Mellish also permitted access to their collection, put us in contact with William Casford, and gave us two marked P.E.I. Pottery pieces for the Royal Ontario Museum's collections. William Casford was generous of his time and memory. Janet Holmes of the museum staff researched the history of the business in the Provincial Archives and Land Records Office; Lonnie (Elizabeth) Webster handled artifact control and recording, and Nancy Willson did the post-excavation conservation and drawing.