Articles

Nineteenth-Century Canadian Importers' Marks

Abstract

Pottery and porcelain with a Canadian importer's mark are one of the most useful and reliable ways to document the Canadian ceramic trade in the nineteenth century. The importer's mark clearly states that a specific type of ware, in a specific pattern, was being sold in a defined area, at a date that can be determined. It adds to our knowledge of the taste and economic status of importer and customer.

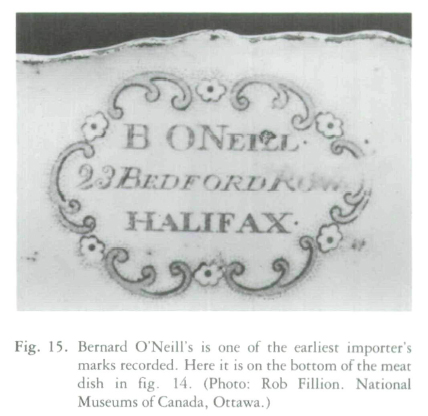

Marks of this kind first came into use in Canada in the 1830s, a period that coincides with the rise of the china merchant. It is significant that all the early marks so far recorded are for dealers in supply centres such as Halifax, Saint John, or Quebec City. It was to these wholesalers that country storekeepers came for their stock. The wares with these nineteenth century marks indicate the type of importations that formed the bulk of the Canadian trade. In the twentieth century importers' marks proliferated and were increasingly reserved for the better or more expensive class of goods; in the nineteenth, they are found in most instances on printed earthenware and on ironstone china. Occasionally wares with an importer's mark also carry a potter's name, or they may point to one through a known pattern. In this way they are yet another means of identifying suppliers of the Canadian trade.

Résumé

Les poteries et porcelaines portant l'estampille d'un importateur canadien comptent parmi les moyens les plus utiles et les plus sûrs pour se renseigner sur le commerce de la céramique au XIXe siècle. L'estampille de l'importateur est très explicite: elle révèle que tel modèle de tel arti-cle était vendu dans une région définie, à une date qui peut être déterminée. Elle permet de mieux connaître les goûts et la situation économique de l'importateur et de ses clients.

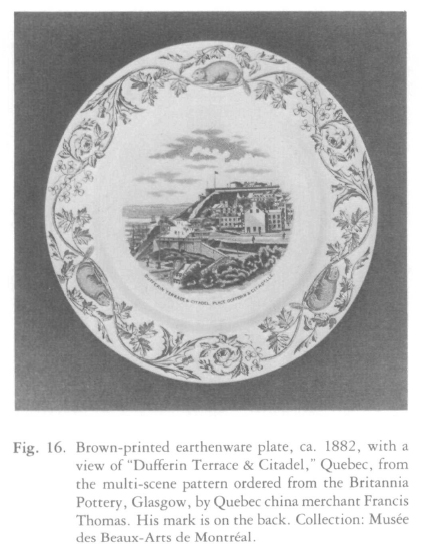

Cet article traite de ce type d'estampilles employées au Canada pour la première fois dans les années 1830, période qui coïncide avec l'essor des marchands de porcelaine. Il importe de noter que toutes les premières estampilles de commerce répertoriées jusqu'à présent se rapportent à des marchands de centres d'approvisionnement comme Halifax, Saint-Jean (N.-.B.)ou Québec. C'est là notamment que les marchands ruraux viennent s'approvisionner auprès des grossistes. Les pièces marquées de ces estampilles du XIXe siècle indiquent le genre d'importations qui constituaient l'essentiel du commerce canadien. Au XIXe siècle, les estampilles d'importateurs prolifèrent et sont déplus en plus réservées aux articles coûteux et de meilleure qualité; au XIXe siècle, on les retrouve le plus souvent sur la faïence et sur la porcelaine opaque. A l'occasion, des articles portant une estampille d'importateur identifient ou désignent le potier par des symboles connus. Elles constituent ainsi un autre moyen d'établir quels étaient les fournisseurs du marché canadien.

1 In documenting the Canadian trade in earthenware and porcelain, nothing presents more objective evidence than wares marked with a Canadian importer's name. With such wares there is no need to rely on the uncertainties of oral testimony or to speculate on how or when these wares arrived in Canada. Unlike tablewares brought by settlers, which obviously must be treated as individual occurrences, the piece with the importer's name makes a clear statement. That statement may be more precise than the cryptic entry in a merchant's ledger or on his bill of sale; it is more precise than many an advertisement announcing "the newest patterns" with never a hint as to what they were.

2 The importer's mark indicates that a specific type of ware in a specific pattern formed part of the Canadian trade at an easily ascertained time and in a defined area. The ware so marked tells the historian something of taste, demand, and the economic status of both importer and customer. Sometimes it points directly to an overseas potter, adding still another name to the growing list of known suppliers of the Canadian market.

3 The earliest china sellers in Canada were general merchants. They were men like the erstwhile fur trader Joseph-François Perrault, who was selling "plain and painted earthenware" in Montreal in 1790 and dealing in goods too varied and "too tedious to mention" in his Gazette advertising.1 They were men like the transplanted French royalist, Laurent Quetton de Saint-Georges, who journeyed from York (Toronto) to Montreal in 1804 to lay in supplies of snuff and sleigh bells, as well as crockery.2 They were men like James Peake, who emigrated from Plymouth to Charlottetown and was dealing in rum and earthenware in 1824, and Horatio Curzon, who had been a china merchant in Liverpool but who was selling Swiss muslins along with "Earthenware of all description in any quantity" in Halifax in 1836.3

4 Ceramic wares in the early days stocked every general store. Nova Scotia's Cunard and Company sold earthenware as well as sailcloth. Quebec's George Pozer not only dealt heavily in earthenware and was an agent for an English pottery, he also sold groceries, supplied the garrison, bought and sold real estate, and acquired the famous Chien d'Or hotel. (In 1805, when a rival hotel collapsed, Pozer the money-making china seller, was seen wearing his cocked hat and "strutting up and down in front of the ruins in great glee.")4

5 None of the earliest importers of pottery and porcelain called themselves anything other than general storekeepers. Gradually, however, the "china merchant" emerged. Among the first were Joseph Shuter and Robert Charles Wilkins. In Montreal's first directory (1819) Shuter and Wilkins were listed as china merchants. Yet the partners by no means restricted their business to ceramic wares: they sold cheese, tarred cordage, and country produce. But the term was on its way to becoming established, and by the 1830s it was in frequent use. By that time, an importer selling a substantial quantity of pottery and porcelain was apt to call his place of business a Staffordshire warehouse. Charles Jones of York was advertising his "Staffordshire Ware-House" in 1831 and Samuel Cooper of Saint John his "Staffordshire & Yorkshire Warehouse" in 1838.5

6 It is now impossible to state with assurance why only certain dealers and only some of their wares were identified by an importer's mark. There were probably a number of reasons. A name on the back of tableware was — and is — a good advertising ploy. In the list that follows it is significant that the earliest marks are all for importers in areas that were supply centres for dealers in less populated districts. There was keen competition on the part of importers in the larger centres, not only for the considerable local trade, but also for the wholesale trade with country storekeepers. Montreal, for example, was a major supply centre for Upper Canada at the time Shuter and Wilkins were in business. There is a relationship between the earliest importers' marks, the type of importers using them, and the geographical location of those importers.

7 What today are called "in-house brands" undoubtedly had their nineteenth-century counterparts. The importer's mark may be an indication that only one dealer would distribute that particular pattern in Canada, or at least in a particular area in Canada. Again, a pattern bearing an importer's name may have been produced to that importer's specifications. An example would be the multi-scene pattern of Quebec views made in Scotland for Quebec china merchant Francis Thomas. A dealer who had conceived the idea of a pattern he felt confident would sell well in his area would wish to make sure it went to no one else. In this connection, it is interesting that although Thomas must have handled a vast number of patterns in the quarter century he was in business (and his business continued after his death), this is the one pattern so far recorded with the Thomas name.

8 In Nineteenth-Century Pottery and Porcelain in Canada (1967), I published the marks then known to me. The expanded list below includes all I have noted since. It gives the importer's name, the mark (all are printed marks), the type of ware on which the mark appears, the potter (where known), and a contemporary reference. The date following each name is the approximate date of the piece on which the mark appears. The list does not include names which appear on salt-glazed stoneware (jugs, crocks). Marked wares of this type were often of local manufacture and fall into a different category. Unfortunately space does not permit me to provide details of each importer's business.

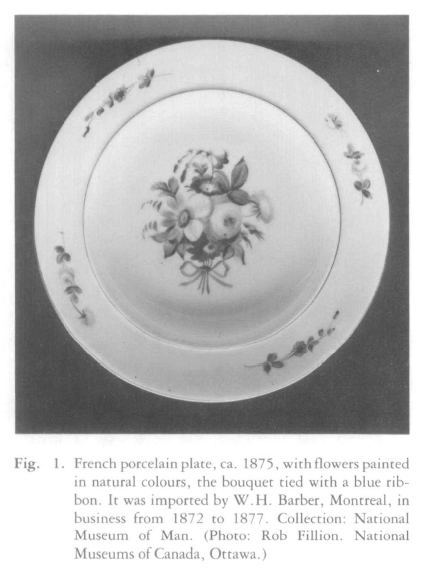

Display large image of Figure 1

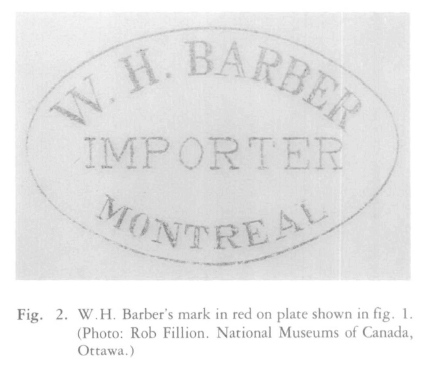

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

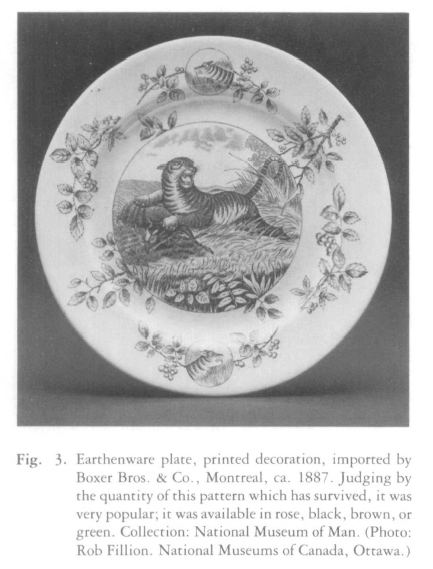

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

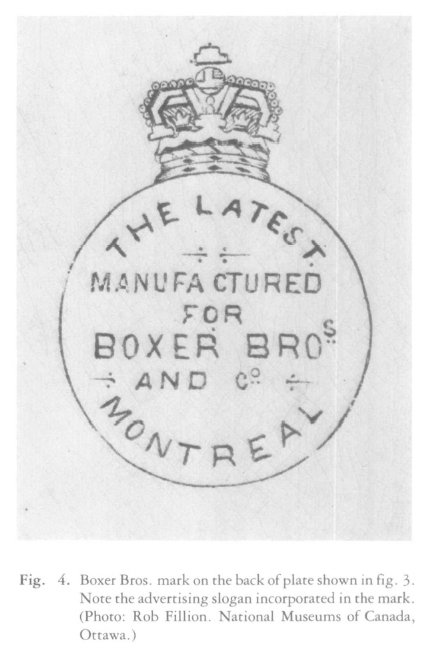

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

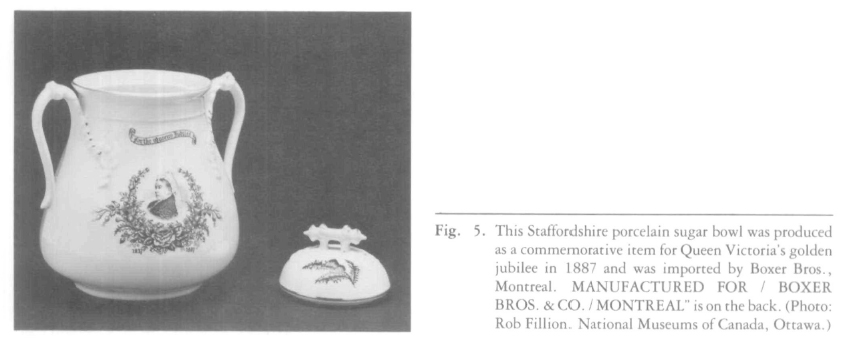

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

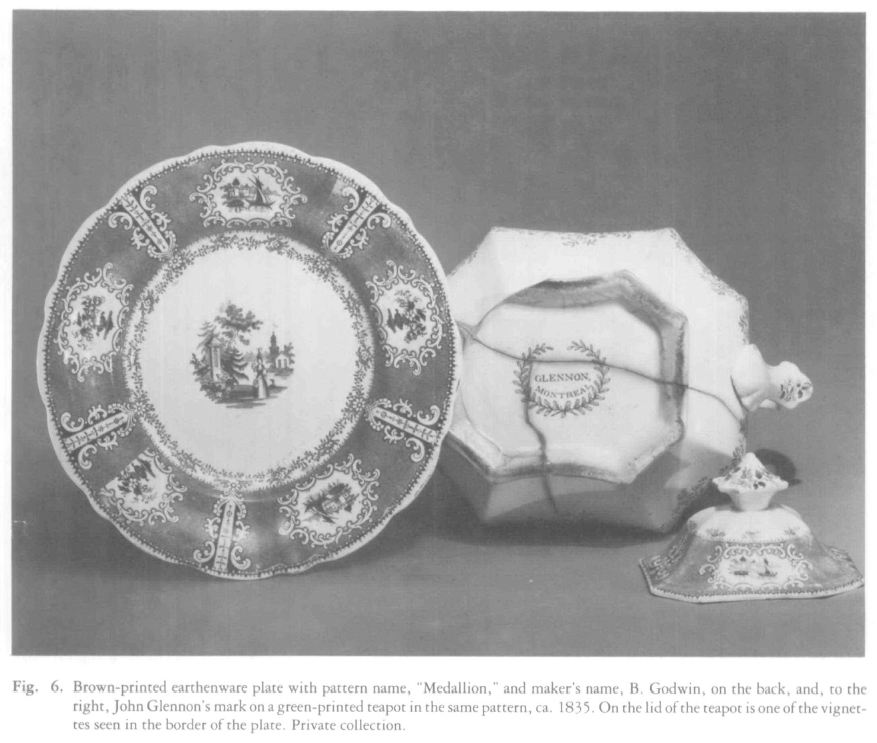

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

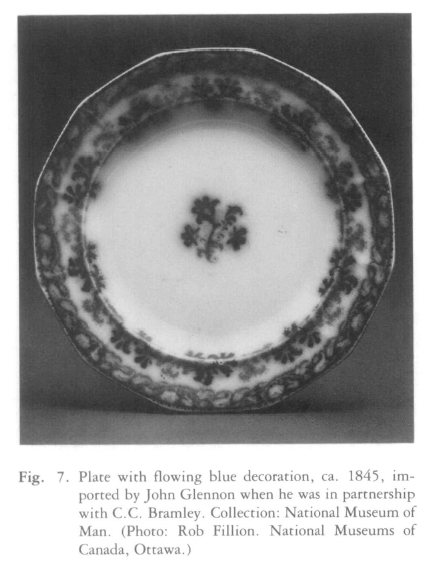

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

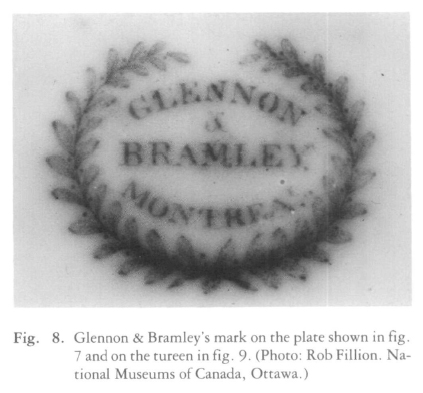

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

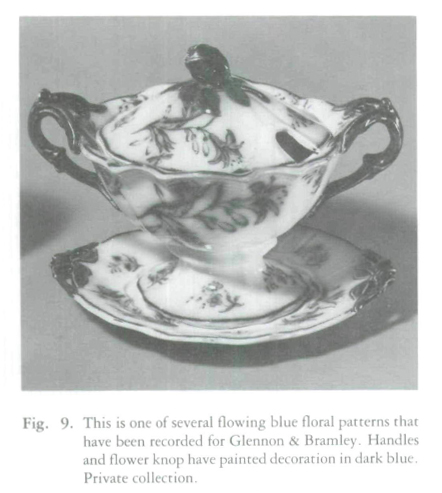

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

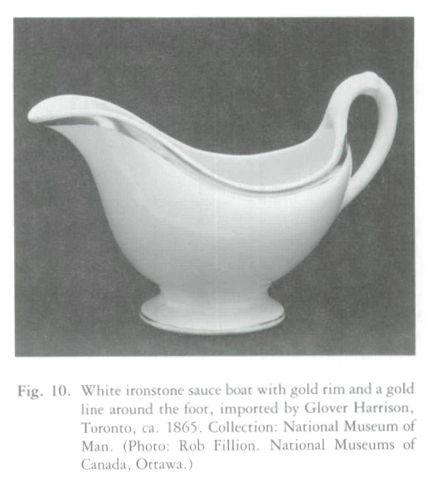

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

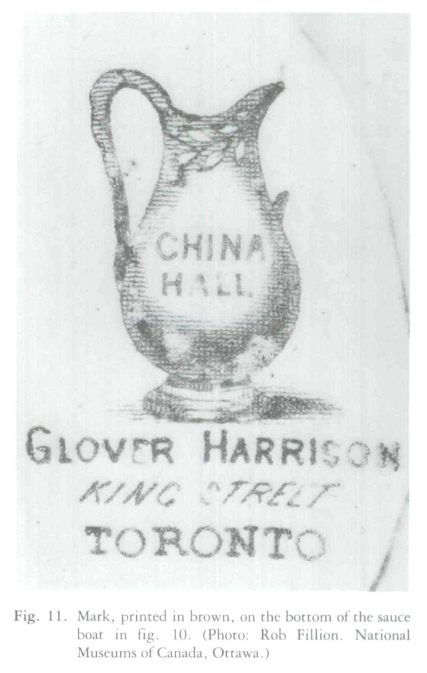

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

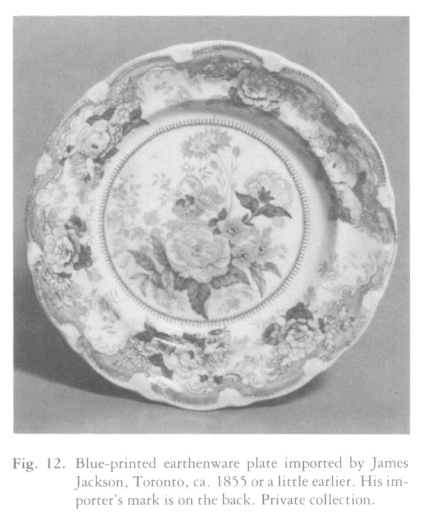

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

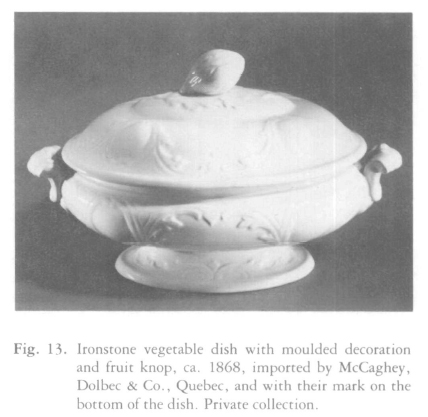

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

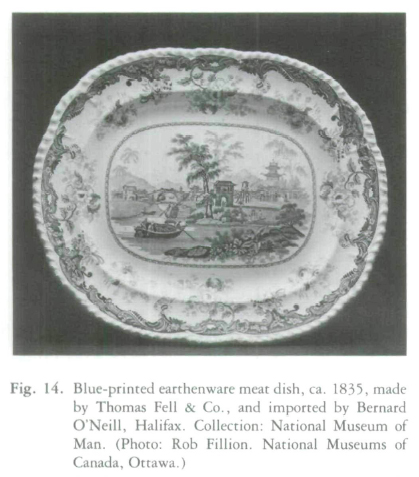

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15 Display large image of Figure 16

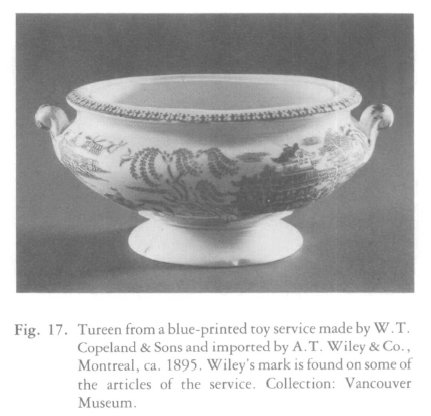

Display large image of Figure 16 Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17