Furniture / Meubles

Decorated Walls and Ceilings in Nova Scotia

Abstract

This article outlines the history of decorative wall treatment and deals in detail with the discovery and description of a number of painted rooms in Nova Scotia.

Résumé

L'auteur fait l'histoire des peintures murales, puis décrit en détail plusieurs pièces peintes de Nouvelle-Ecosse, tout en racontant leur découverte.

1 In The Stones of Venice, John Ruskin made the following statement: "Remember the most beautiful things in the world are the most useless: peacocks and lilies for instance."1 Decorative painting does not serve any useful purpose — it does not make a wall more sound-proof or a ceiling sturdier — but it does make them more beautiful.

2 I became interested in decorative painting after I had been taken to see the Croscup Room.2 This room, familiar to Nova Scotians, may be unknown to others. In 1844, William Croscup and Hannah Amelia Shaffner married and moved into a modest home in Karsdale on the shore of the Annapolis Basin.3 A few years later, probably in 1848, the walls of the west parlour of their home were decorated by an anonymous artist, who, according to family history, was a British sailor who had jumped ship.4 He covered the walls with scenes depicting Micmacs, the launching of a ship (William Croscup was a shipbuilder), London's Trafalgar Square with the newly constructed National Gallery and St. Martin's-in-the-Fields, as well as a scene showing St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Above the mantle Queen Victoria presided in a grand drawing-room (the Croscups were of Loyalist stock).5

3 Hannah Amelia Croscup had always prized her painted room. During her lifetime, no child was ever allowed to set foot in it; they could peek into the room but not cross the threshold. To her the room was a treasure.6

4 I was taken to see it by one of her great-granddaughters in 1960. When the door to the room opened, I could not believe my eyes. Although the paintings were dirty, they shone with a jewel-like quality. The scenes were so vivid, they sparkled as if they had been painted yesterday.

5 About a week later, on my return to Halifax, in an effort to draw attention to this provincial marvel, I did a broadcast on CBC radio about it and CBC television filmed a show. Even at that time the paintings were flaking and in need of care, but in 1960 there were few institutions that could be approached. Nova Scotia did not have a provincial art gallery, nor did it have a museum of fine arts or a department of culture. The explosion of interest in the arts had not yet begun. My efforts to arouse sympathetic interest in the Croscup Room failed.

6 Over the years I continued my efforts to promote interest in the Croscup Room which resulted, in 1976, in its purchase by the National Gallery. It was removed to Ottawa, extensively restored, and is now on display there. Overnight my ugly duckling had become a lovely swan — indeed it was now called "a national treasure." I felt saddened at the moving of the Croscup Room, but it started a train of thought. Would that have been the only room in the province? Might there not be another somewhere?

7 The question of other painted rooms intrigued the Provincial Department of Culture, Recreation, and Fitness and I obtained a small grant. Armed with a camera and notebook, I set out for the great adventure. The first problem was to obtain information on locations where I might find examples of decorative painting. I wrote letters to the weekly newspapers explaining my problem, I talked about it on radio, and wherever I went I asked questions. As for written information on the subject, there was none. The outcome of this part-time survey surpassed all my expectations and resulted in my receiving two successive grants from the Explorations Programme of the Canada Council.7 I thought this would complete the project, but I had underestimated the hidden riches of decorative painting in Nova Scotia.

8 Decorative painting is an old form of the decorative arts and can be found on interior walls, ceilings, floors, furniture, household objects, carriages, and sleighs. The raw materials were usually at hand and it provided a simple way to bring a touch of colour into the home. After a period of declining interest, it became fashionable again in Europe in the eighteenth century. Popular were scenes from mythology, chinoiserie, biblical scenes, and Arcadian pictures with shepherds and shepherdesses looking at one another with adoring eyes instead of watching their flocks.

9 The rediscovery of Pompeii in 1748 and the extensive use of wall-paintings there was what gave rise to this trend in the decorative arts.8 In the eighteenth century the rich young man went on the Grand Tour which included a visit to the great art centres of Florence and Rome; now Pompeii became part of the circuit. The sight of the wonderful frescoed walls and the extensive use of marble columns brought new ideas in art and fashion. Marble was easily procured in Italy, but much less readily available in England. However, deception was the order of the day. If you did not have the real article, you imitated it. Despite this, I was surprised to find that the walls in the hallway of Number 1 Royal Crescent in Bath, England, were marbleized. The Royal Crescent was built by John Wood the younger in 1767 mainly to rent out during the season when it was the fashion to take the waters at Bath. One of the tenants of Number 2 is reputed to have been the Princesse de Lamballes, a friend of Queen Marie-Antoinette.9

10 It did not take long for news and fashions to cross the Atlantic. As early as 1750 Gerardus Duyckinck advertised in the New York Weekly that he had received "a fine assortment of Sea Skips and Land Skips and Entry and Stair Case pieces already framed."10 Here in Nova Scotia, Michael Francklin, an up-and-coming young man, had in his home on Buckingham Street in 1760, "two good reception rooms, decorated with great taste in colours by artists from New York." Perhaps he had imported some of those "fine Sea Skips or Stair Case Pieces."11

11 At the same time hand-painted wallpaper became stylish. Until the invention of roller printing, it was made in small sheets, roughly twenty-eight by forty-five centimeters, printed with a design and then hand-painted.12 In 1823, Silas Hibbert Crane ordered from Boston a paper painted by the French artist Joseph Dufour for his new home in Economy, Nova Scotia. The subject was "Telemachus on the Island of Calypso." One room in the house was specially constructed with rounded corners and only one window so as not to interrupt the pattern. The cost was £100, an enormous sum at the time.13

12 Why did decorative painting become so fashionable and so widespread? It provided a cheaper and more readily available alternative to both framed "Land Skips" and wallpaper. Framed painted scenic views and wallpaper were imported from France, England, or Boston. In 1851, James Dawson of Pictou, advised the public in the Eastern Chronicle that he had "just opened fifty New Patterns of splendid British Paper Hangings."14 It was not until the repeal of the tax on wallpaper in 1838 and the invention of the roller-printing machine that the price of wallpaper dropped considerably.

13 The earliest recorded manufacturer of wallpaper in Canada was the firm of MacDonald and Logan who worked at Portneuf in Quebec in 1843, but it was only in the 1860s that the products of Upper Canadian wallpaper manufacturers began to make headway in the Maritime Provinces.15 After 1850, decorative painting lost its appeal in Upper Canada but not in Nova Scotia. Paint was cheap, it could be made at home, and the painter often came to the house asking for little money.

14 There was one big difference between Canada and Europe. In Europe, decorative painting was done by the great artists of the day. In France, Fragonard was commissionned by Madame Du Barry to decorate her pavilion at Louveciennes and the son of François Boucher, Juste, who was an architect and decorator, did similar work. In England, Angelica Kauffmann painted delicate ceilings.16 In 1888, Gustav Klimt was commissioned to decorate the ceiling of the New Theatre in Vienna and, although the Emperor Franz Joseph was very satisfied, Klimt was not because he felt that such work was beneath him as an artist.17

15 In Nova Scotia the house-painter provided the service. Smithers and Studley advertised in the Halifax Monthly Magazine in 1830 that they were "decorative and general painters."18 William A. Smith informed the public in the Liverpool Transcript that he "painted furniture in the neatest and most fashionable style."19 Even Valentine, the well-known portraitist, had to resort to doing decorative painting to make ends meet.20

16 Painters had stencils, sometimes their own, sometimes out of pattern books. These produced a repetitive pattern combined with striping. The mouldings were painted in different colours to offset the trailing vines, acanthus leaves, swags or garlands of flowers. The painter who had just that little extra flair and imagination used freehand. Often a combination of both was used to produce the desired effect.

17 Although local artists do not appear to have used trompe-l'oeil, they used other forms of deception. Wood graining was a favourite. Wood used in Nova Scotian homes is nearly always pine. The technique of wood graining could make doors look as if they were of bird's-eye maple or oak. Then there was marbleizing. With a little bit of magic a plain pine mantle could be turned into a marble one. Recently I saw an elegant pink marble wall in a house in Canning — imitation, of course. Rufus Porter, one of the most famous New England decorative painters, gave explicit directions on how to do graining and marbleizing. Porter was also the founder and first editor (1845-47) of the Scientific American. In 1846 he wrote a series of articles on landscape painting on walls which he considered a craft. Bark on trees was produced by "giving a tremulous motion to the brush"; foliage was painted with a "brushing stroke." Stencils should be used for buildings and ships.21

18 These house-painters had been taught their trade. First they carefully prepared the surface to be painted, then they ground the colours and mixed the paints. In one house, the paint marks are still visible on the floor. The painters took great pride in their work which may be the reason why most of the examples I have seen are in such good condition. Although dirty, they are rarely flaking or separating from the surface. The house-painters would have been very surprised to hear themselves called artists." In the census they describe themselves as "painters."22 They turned their hand to anything. House- and sign-painter, H.C. Holmes advertised in 1854: "All orders for House, Ship, Ornamental or Plain Sign Painting executed in the most prompt manner. Imitation of all kinds of wood and marble, executed in a stile surpassed by none. Also old chairs repainted and ornamented."23 Often they were itinerant workers, who did the work for board and lodging with a few dollars thrown in.

19 Most of our early folk artists were anonymous. I have yet to discover a name or initials on a work. If I know their names it is because old people have remembered them, or their descendants could tell me, and in rare cases I have a photograph. I recognize them by their individual style. In the 1880s and 1890s there was a resurgence of interest in decorative painting and the hand of the prolific Lyons Brothers can be seen far afield. They were masters in stucco-work which they painted afterwards. Their garlands of roses are as good as a signature.

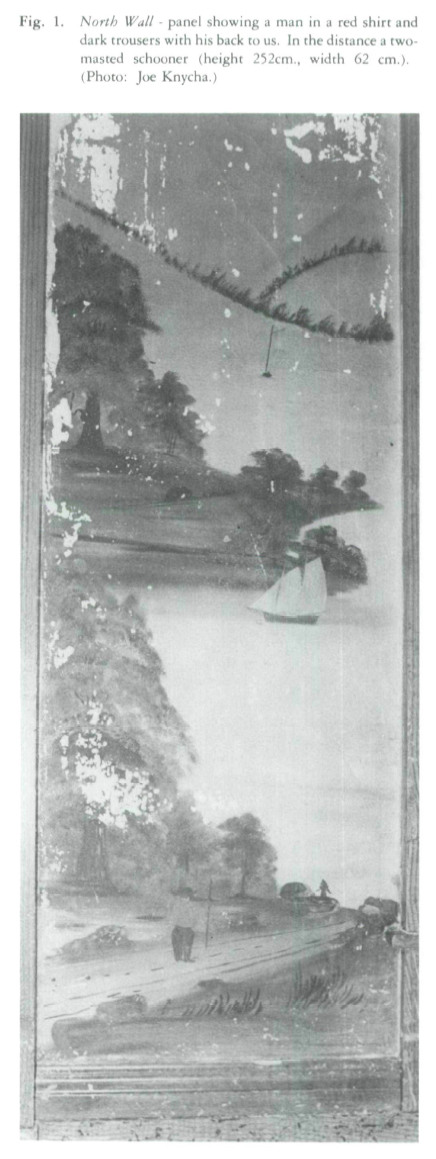

20 Today decorative painting has come into favour once again. People cut their own stencils of plastic instead of paper or architect's linen. They can be ordered from places that specialize in the revival of the old crafts. Freehand is also used.

21 I have been in pursuit of decorative painting for four years and have found an unbelievable amount of work still in existence. So far I have photographed eighty locations and more are waiting for me. I have found examples of all techniques and many freehand designs decorating a fire board or a panel in a hall. Each new find has delighted me, but what I wanted most of all was another room like the Croscup Room. There should be another one, but no one seemed to know.

22 Then ... it happened. Mrs. Parker lives in an old seventeen-room house in South Williamston. She had redecorated sixteen rooms and had just decided to tackle the last one. One Monday morning in January 1981 she began to peel off layers of wallpaper. To her surprise she uncovered not blank plaster, but a mural. Her curiosity aroused, she continued at a rather more frenzied pace and in the end the Parkers found they had their own "Painted Room." The news spread and two days later I was driven through a fairly benign snowstorm to the old house on the back road. I walked in and there it was! Not stencilling, not striping or marbleizing, but painted pictures all over the walls.

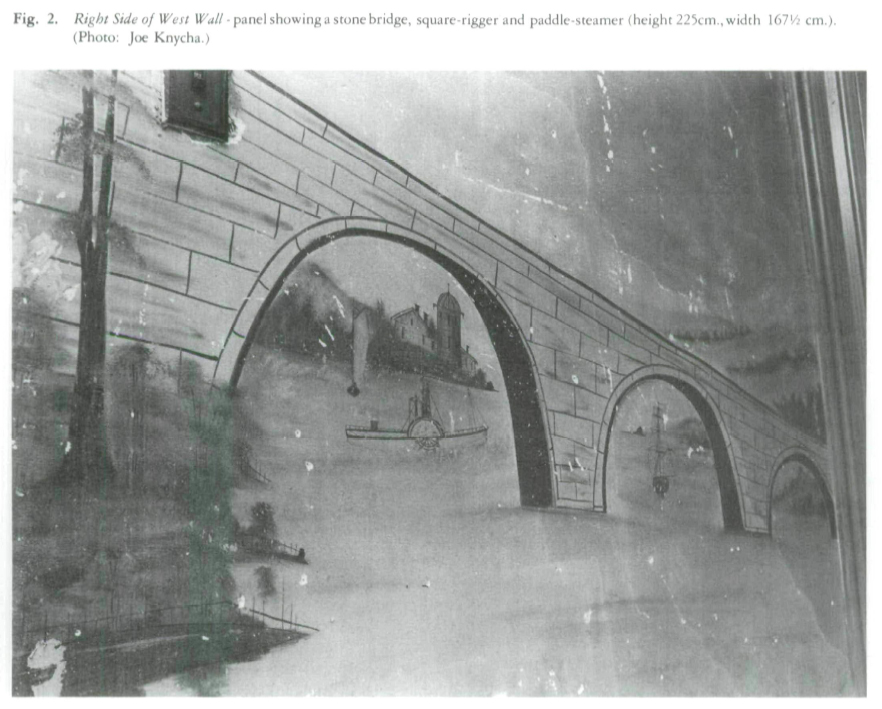

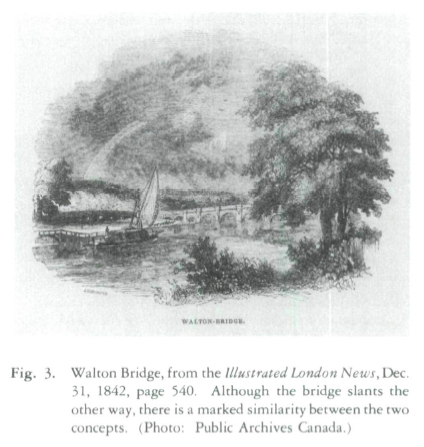

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 123 What did the artist paint? Over the mantle was a large low bowl filled with fruit and flowers. Apples, grapes, squash, and plums mixed with apple blossoms and a sort of dahlia. The artist had painted extraordinary structures of grey stone blocks, (structures never seen in Nova Scotia), a bridge with three arches, and a building like a Crusader castle (fig. 2). However, his most spectacular exploit is on the east wall. The left panel shows a two-masted schooner of which hundreds were built in Nova Scotia (fig. 1). On one side stands a workman; on the other the proud owner dressed in black frock-coat and hat with round crown. The right panel shows a lady dressed in blue, walking towards a building of extraordinary design. It is as if the artist had put the Taj Mahal and the Washington Capitol into a big pot, stirred them around, and produced this concoction.

24 The room must have been decorated shortly after the house was built in the early 1860s. The style of dress and the split topsail of the square-rigger are of that period. The mysterious thing is that not a single person who grew up in the house or visited there around 1900 ever heard a mention of this "Painted Room." Did the family not like the room and covered the walls with wallpaper shortly afterwards?

25 Where did the artists get their ideas? The Parker-Shaffner artist was a folk artist in the grand manner. His knowledge of ships was sketchy; there are details on the schooner that no shipbuilder would allow. But he puts it all together with verve — the room sings. The Croscup Room artist definitely had had training, probably in topographical drawing. Both painted large murals, complicated in composition and design, of scenes they had never seen. How was this accomplished?

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 226 The answer lies in the illustrations published in that fountain of knowledge and information, the Illustrated London News, which began publication in 1842. This amazing weekly was like television in that it presented the news in pictures. Queen Victoria's travels, her castles, the earthquate in Algiers, the launching of a ship, the funeral of the Duke of Wellington were all reported at length and illustrated.

27 The Croscup Room artist must have had access to the publication. Faithfully he depicts Trafalgar Square as it was featured the Illustrated London News in September 1842. It is interesting to read in the accompanying article that the new National Gallery was described as "tasteless and ill-devised." The scene from St. Petersburg, also on a wall in the Croscup Room, appeared in August 1842 on the occasion of the visit of the king of Prussia to the czar of Russia. Queen Victoria, painted above the mantle, was receiving King Louis Philippe of France and the Illustrated London News reported this in October 1844.24

28 The Parker-Shaffner artist too must have seen the weekly. His lady in blue is walking towards the Capitol, the bridge resembles Walton Bridge across the Thames, and the Crusader castle may have been inspired by the picture of the Norman Gate and Prison House at Windsor Castle. He altered many details, but there is a similarity.25

29 The year 1981 was a most rewarding one for me. Not only did I find the Parker-Shaffner room in January, but two months later another painted room came to light in a Bear River house said to have been built betwen 1785 and 1790. In 1835 it was bought by John Barr, inspector of customs, who made it into an inn called "The Golden Ball."26 The walls were decorated while he owned the inn.

30 In 1922 this house was bought by the Great War Veterans' Association to serve as a clubhouse. Finding the front room dingy, they proceeded to strip the walls which turned out to be entirely covered with murals. The secretary of the association described the scenes in detail in letters, which have fortunately been preserved, asking for advice and help.27 No one knew what to do, and the walls were covered with wallpaper until recently, when one panel was stripped. Though darkened by varnish and dirt, this recessed panel measuring less than a metre square, is spectacular. It shows a house of classical proportions set in a landscape with a huge oak tree; in the foreground are two cows lying down and one small and endearing droopy horse. The inspiration again comes from the pages of the Illustrated London News, the house being Claremont, the country residence of Princess Charlotte, daughter of the prince regent, and Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg.28

31 The question is, When was this room painted and by whom? Judging by the one uncovered panel, I think it may have been painted around 1845. When the other walls, which apparently contain ships, houses, and people, are laid bare, it will be possible to provide a more accurate date for the work. It was not done by the Parker-Shaffner artist because the style is quite sophisticated and resembles more closely the work in the Croscup Room.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 332 One uncanny feature about the three rooms is that the Croscups keep cropping up. Mrs. Croscup's second daughter Mary married her distant cousin William Judson Shaffner in 1867 and went to live in the South Williamston house that has a painted room.29 Two of William Croscup's uncles, Ezekiel and Zebediah, moved to Bear River. They built ships there and William is mentioned several times as being at least a shareholder in the shipbuilding venture.30 Is this just a coincidence, or was a liking for painted rooms transmitted by the Croscups? I have no proof, and yet I feel some explanation is eluding me and that I am seeing "through a glass darkly."

33 I began this search without having any idea where it would lead me. At first my findings consisted mainly of walls decorated with stencilled designs executed with considerable skill. But in the last year important wall paintings have come to light. Overmantels of outstanding quality that may date from 1830 and more rooms are on my list. Now as I drive through the province and pass houses I ponder the treasures that they may contain. I might stumble across another painted room. How strange that, had the Croscup Room, my ugly duckling, not been taken to Ottawa, I might never have started on my joyful quest for examples of decorative paintings in Nova Scotia.