Furniture / Meubles

Thomas Nisbet:

A Reappraisal of His Life and Work

Abstract

The life and craft history of Thomas Nisbet (1777-1850) is given here; his work is related to that of other New Brunswick cabinet-makers of the period and the problems of accurate attribution are discussed.

Résumé

Cette communication donne un compte rendu de la vie de Thomas Nisbet et de son évolution comme artisan (1777-1850), en situant sa production par rapport à celle d'autres ébénistes du Nouveau-Brunswick à la même époque et en examinant les problèmes d'attribution.

INTRODUCTION

1 Interest in New Brunswick furniture has increased in recent years, particularly in pieces made by early cabinet-makers such as Thomas Nisbet. As a result, numerous pieces of furniture are attributed to Nisbet although often on little more than the fact that the pieces are mahogany and have rope-turned legs. Disturbed by the lack of a factual basis for such attributions, I began to investigate Thomas Nisbet's life and furniture. This study has clarified a number of details about Nisbet but it has also raised a number of questions about his life and work.

Early Life and Training

2 Thomas Nisbet came to New Brunswick from Scotland in 1812 at the age of thirty-five or thirty-six.1 Since most apprenticeships lasted seven years and boys started their apprenticeships at fourteen years of age, Nisbet worked for at least fifteen years in Scotland as a cabinet-maker in addition to his apprenticeship. He is reported to have apprenticed with his father, but it is not known if he subsequently worked with his father or in a shop owned by someone else or if he had a shop of his own?2

3 Although he was a native of Dunse, Berwickshire, Nisbet's marriage certificate in 1803 stated that he was a "wright" in Glasgow.3 His first newspaper advertisement in Saint John in 1813 stated that he had lately come from Glasgow.4 Not much is known about his family in Scotland, but advertisements in Glasgow newspapers suggest certain possibilities.

4 John Nisbet, a Glasgow wright, wood measurer, and auctioneer, may well have been Nisbet's father.5 John Nisbet died in 1812, the year Thomas came to Saint John, and his stock of mahogany, wright's tools, etc. were sold by auction.6 An advertisement in 1793 by the Turners of Glasgow mentioned a William Nisbet who may have been Nisbet's only brother.7 It can be suggested that William came to Saint John to work with his brother in either 1816 or 1819 when Nisbet ran advertisements that he had engaged experienced turners from Europe and the Old Country.8 This would correspond with the fact that William came to New Brunswick late in life since he would have been in his mid-forties at this time.9 Nothing has been found in the records about Nisbet's brother until the 1830s when he was active in the Wesleyan Sabbath school and worked with the poor, the insane, and sick emigrants; he may have been semi-retired at this time.10 William died in 1841.11

5 No comparison of Nisbet's early work with quality English or Scottish Regency furniture has been made. Nisbet has been termed the Duncan Phyfe of New Brunswick, and yet no comparison of his and Duncan Phyfe's work has been done.12 Based on the few labelled Nisbet pieces made in his later period, it would appear that he, like Duncan Phyfe, followed the declining nineteenth-century styles and during those years produced clumsy degraded Empire.13

6 Nisbet is well known because he labelled some of his furniture. Different authors have speculated about what caused him to label certain pieces and not others.14 He was the only early Saint John cabinet-maker known to have used paper labels other than Daniel Green who advertised that he used paper labels from July 1815 to November 1817.15 Unless Nisbet had experience with labels in Glasgow, it is possible that he began the practice at the same time as Green.

Cabinet Business

7 Nisbet commenced business as a cabinet-maker and upholsterer in April 1813 on Prince William Street in Saint John.16 He maintained a shop on Prince William Street — although at several locations — until retiring from cabinet-making in September 1848.17 In his first advertisement, he listed two eight-day clocks with mahogany cases for sale, but there was no indication whether he made the cases or whether the clocks were imported.

8 An advertisement in early 1815 was the first to emphasize the importance of upholstery in his business; he informed his customers that he made bed and window curtains and that as he had received baked hair and hair cloth from England he could now fill numerous outstanding orders.18 He also advertised for eight to ten thousand feet of birch boards and announced that he was importing a full supply of mahogany from the West Indies. This shipment arrived in Saint John from Jamaica in March.19 He was the first cabinet-maker in Saint John to import his own mahogany and he subsequently often advertised mahogany for sale at his wareroom.20

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 His first advertisement in Fredericton appeared in 1815 when he told customers that Mr. Mark Needham would receive orders and forward them to Saint John.21 An advertisement in mid-1816 emphasized that he would supply furniture in both mahogany and birch.22 Nisbet evidently made a lot of birch furniture but no pieces have been found with labels; several maple pieces with labels are known (fig. 1). Country orders were encouraged in much of his advertising.23

10 In 1817, Nisbet shipped to Fredericton a sloop load of furniture which was to be soldat the house of a Mr. McLeod (presumably McLeod Inn).24 The shipment included mahogany, maple, and birch furniture as well as three mahogany eight-day clocks and one maple eight-day clock. This is the first time he specifically mentioned that he had Windsor chairs for sale although later advertisements offered Windsor and fancy chairs.25 It is not clear whether Nisbet made the Windsor chairs or just sold them as he sold so many imported small furniture items such as dressing-table mirrors, portable writing desks, tea caddies, etc.26 Nisbet may have made at least part of the chairs since he imported twenty-four chair seats from New York in 1830.27 Huia Ryder showed a picture of a pine yoke-back Windsor which had Nisbet's name stamped under it. However, I have not been able to verify this piece personally because the chair has disappeared.28

11 Nisbet advertised many times that his firm did all kinds of turning and carving on lowest terms,29 which suggests that he in fact did piece-work for other cabinet-makers, a practice not uncommon in the trade.30 If he did piece-work, it becomes more difficult to make attributions to Thomas Nisbet.

12 About 1822, Nisbet joined James Stewart to form Jas. Stewart and Company which imported a general assortment of British and Fast India goods for sale at its store on Saint John Street.31 This firm closed in May 1828.32 This importing is reflected in advertisements for Nisbet's Cabinet and Upholstery Wareroom; in addition to miscellaneous small imported furniture mentioned previously, he now mentioned cabinet mountings, curtain pins, picture frame mouldings, and other items for the home.33

13 On 8 April 1824, a fire destroyed a portion of Saint John, and among the principal sufferers was Thomas Nisbet.34 He lost his house, together with the furniture wareroom and an extensive range of buildings in the rear, comprising workshops, stables, etc., which he had recently purchased and fitted up. Nisbet subsequently ran an advertisement asking for early payment by those indebted to him so that he could in some measure replace his stock.35 There is no evidence in the property records that he was forced to mortgage or sell property to begin again. By 15 April he had moved to former premises and was continuing the business of cabinet-maker and upholsterer.36

14 In the summer of 1829, Nisbet advertised a large auction of furniture at his wareroom.37 In addition to birch and mahogany, the furniture was made of bird's eye maple, pine, and rosewood. In June of the following year, Nisbet had "an extensive and elegant assortment' of mahogany and birch furniture for sale at Mr. Robert's store on Queen Street, Fredericton.38 On 1 July, he sold the remainder of the furniture by auction. Auctions of "surplus" new cabinet furniture by cabinet-makers such as Thomas Adams and Alexander Lawrence were frequent during the late 1820s and early 1830s.39

15 The first advertisement in which Nisbet mentioned that he attended to funerals appeared in 1827 although he was in fact involved in the business before this time.40 Funerals became more important to Nisbet's firm after his sons joined the business and as the Victorian preoccupation with funerals made them more lucrative.41 By the 1840s, in addition to the coffin, Nisbet provided shrouds and caps, linen and ribbon, scarves and had a hearse for hire. Some confusion exists as to when Thomas Jr. joined the firm as a partner.42 However, Nisbet advertised extensively that he had taken his son Thomas into co-partnership under the name Thomas Nisbet & Son in 1834.43 He changed the wording on his furniture label at this time to reflect this partnership.

16 Nisbet advertised much less frequently in the 1830s and 1840s, perhaps because of his increased involvement in other areas, such as the Saint John Hotel Company and the Saint John Mechanic's Whale Fishing Company. He served as president of the Saint John Hotel Company from its inception in 1837 to 1849, and of the Saint John Mechanic's Whale Fishing Company from its inception in 1835 until his death in 1850.44

17 When Thomas Jr. died in 1845 at the age of 35, Nisbet placed a public notice in the newspapers settling demands for and against the firm and his son's estate.45 In true Scottish fashion, he made use of the same advertisement to say that he had on hand an extensive assortment of superior furniture. Nisbet did not dissolve the firm Thomas Nisbet & Son until 1848 when he assigned all his furniture, materials, and tools to his son Robert; the business was then carried out by Robert Nisbet on his own account.46

Employees

18 If the quantity of advertising (both to sell furniture and to hire journeymen cabinet-makers) and the number of government contracts are any indication, the output of Nisbet's shop was greatest in the 1820s. During this period, he advertised for two apprentices and up to sixteen journeymen cabinet-makers.47 While in partnership with his son Thomas — a period of fourteen years — he advertised for no more than nine journeymen cabinet-makers.48 Only three advertisements for runaway indentured cabinet-makers or apprentices were placed in the Saint John newspapers by Nisbet.49 These occurred at a time when the firm's output was presumably highest and one would assume the greatest number of persons were employed. No information has been found as to his total number of employees during any of these periods.

19 Nisbet's output, his reputation, and his business acumen are well illustrated by the amount of work he did for the province. When the arrival of Lieutenant Governor Sir Howard Douglas was imminent in 1824, the New Brunswick House of Assembly allotted the sum of £750 sterling to provide for suitable furniture for the public rooms of Government House.50 In addition, funds were made available for fixing up the residence. Nisbet was involved in some of the repairs and he received in excess of £170 for his work.51 It is not known what these repairs involved since the accounts are missing from the House of Assembly papers. (It is interesting that during the same period, Nisbet received £19 4s. 1½d. for procuring a residence in Saint John for the use of the lieutenant governor.52)

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 220 Originally the plan was to obtain the new furniture for the public rooms of Government House from England through Bainbridge and Bliss, provincial agents in Liverpool.53 However, Nisbet provided furniture valued at £801. 16s. 4½d. and an unspecified number of chairs at £80 5s. 3d. while Bainbridge and Bliss provided furniture and furnishings totaling £423 19s. 9d.54 Again, details of what furniture and furnishings were supplied by Nisbet are not known. The amount supplied must have been considerable, however, when the cost is related to the price of pieces sold by Nisbet at later dates. In 1832, Nisbet made a table for John Robinson, provincial treasurer, for his office in Saint John at the cost of 15s. and a year later, he made a table and chest for him for £3.55 In 1841, Thomas Nisbet & Son made a mahogany counting-house desk for the mayor's office in Saint John and the following year an armchair with a haircloth cushion for £11 and £1 6d. respectively.56

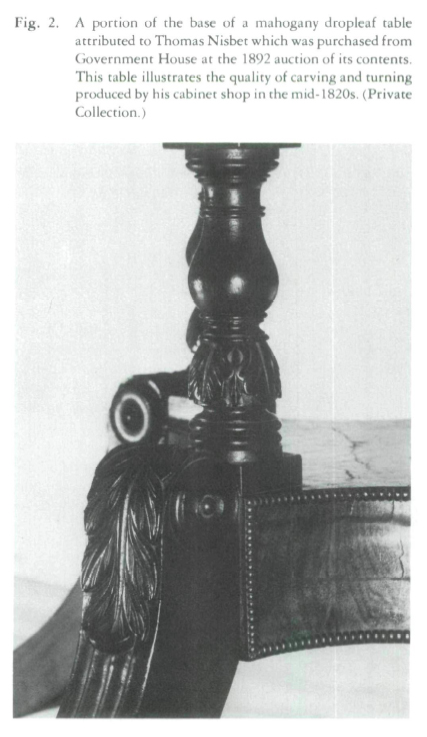

21 On 19 September 1825, the roof of Government House caught fire, and the whole building with the exception of the northwest wing burned.57 Since the fire commenced on the roof, ample time was afforded for the removal of the furniture, which was carried out without damage. Although much of the furniture probably survived it would be difficult to locate because the furniture and furnishings were auctioned in the 1890s (fig. 2).

22 In 1826, an account for an unspecified number of articles provided by Nisbet after the fire was included in a list of accounts turned over to the provincial auditor, Thomas Heaviside.58 In 1827, the accounts for the House of Assembly included £38 7s. 6d. for furniture provided by Nisbet for the executive council chamber in Government House; also included was £82 7s. 10d. for fittings supplied by Stewart and Aitken of Fredericton.59

23 In 1840 and 1841, Thomas Nisbet & Son fitted up and furnished the new council chamber at a cost of £740 13s. 4d.60 Much of this furniture still exists and a number of the pieces are labelled.

Contemporary Cabinet-Makers

24 Alexander Lawrence came to New Brunswick from Scotland in-May 1817, and his first advertisement appeared that September.61 Lawrence did not label his furniture and did much less advertising than Nisbet. In the 1820s, for example, only five furniture advertisements for Lawrence appeared in the three Saint John newspapers while nine appeared for Nisbet. In addition, Nisbet's were larger and listed more items of furniture. Lawrence did not advertise during this period for either apprentices or journeymen cabinet-makers. He must have had both working for him, however, since his 1822 advertisement stated that his mahogany furniture was made by first-rate workmen.62 Since Lawrence apparently did not produce as much furniture as Nisbet, and Nisbet and cabinet-maker Thomas Adams specifically mentioned sofas in their advertisements, it is surprising that few Regency or early Empire sofas are attributed either to Nisbet or Adams while many are attributed to Lawrence.63

25 Several years ago mahogany drop-leaf table with a rope-turned leg was discovered which had an ink stencil of Peter Drake, Princess Street, Saint John, in the drawer. Drake received his freeman's papers as a cabinet-maker at the age of nineteen in 1825.64 At the time he made the table, Drake was operating out of his father's property. In 1840 his father, Jeremiah Drake, leased the property to David Aymar, a son-in-law, with the proviso that Peter have the use of the building during the life of the father.65 Jeremiah Drake died in March 1846, and in 1849 Drake was listed as an innkeeper operating Torryburn House near Saint John.66

26 Drake again advertised in 1853 as a cabinet-maker and upholsterer, in partnership with a man named Watt.67 They mentioned that they did carving and turning at their establishment on Germain Street. Drake continued as a cabinet-maker in Saint John at least until 1866 when he operated a shop at 130 Union.68 Again, we have a cabinet-maker who produced furniture in Saint John with some similar characteristics to that made by Nisbet, but little is known of him. Whom did he apprentice with, since none of his family were in the cabinet-making business?69 What has happened to his furniture and what characteristics does his work have? Does any other marked furniture by him exist?

27 A cabinet-maker and upholsterer contemporary with Nisbet, and about whom little has been written is Thomas Adams. Adams apparently travelled from London to Saint John via Halifax where he took out a marriage bond to marry Jane Williamson in December 1815.70 Thomas Adams and William Smith advertised as partners in cabinet-making, upholstering, and paper-hanging in mid-1816.71 They dissolved their partnership in November of the same year. Adams then set up shop on Prince William close to Nisbet and advertised for two or three journeymen cabinet-makers.72 Over the course of his life, Adams was also in partnership with George Gray (1817-18), a man named Cox, James Whittaker (1834-35), and R.L. Harris (1836)73. If the amount of advertising for journeymen and apprentices is a guide, Adams' output of furniture was similar to Nisbet's in the 1820s. During this period Adams advertised for up to seven apprentices and sixteen journeymen cabinet-makers.74 Adams died in 1837 at forty-five years of age and Nisbet served as one of the executors of his estate.75

28 A tall case clock at the New Brunswick Museum has the name of Adams inside it replacing a lost label.76 Does labelled furniture by Adams exist? At present, no other furniture has been documented or attributed to this cabinet-maker whose workmanship won acclaim during his career.77 What has happened to his furniture and how similar is it to Nisbet's?

29 A large dining-table with some characteristics similar to tables made by Nisbet was recently purchased in Fredericton by the New Brunswick Museum. It is labelled by Daniel Green. Green commenced business as a fancy and Windsor chair-maker in Saint John in May 1812.78 Green's label described him as a cabinet-maker, chair-maker, painter, and turner.79 When he moved to the country near Norton in 1821, he advertised mahogany bedsteads, card-tables, dressing-tables and wash-stands in addition to new chairs.80 Other furniture carrying his label should be found in the Saint John, Fredericton, and St Andrews since he advertised and had agents for taking orders in these locations. The same questions can be asked of him and his furniture that have been raised for the previous cabinet-makers.

30 These are only a few of the cabinet-makers of quality furniture who were contemporaries of Nisbet. What of Scottish cabinet-makers located in other New Brunswick locations, such as Thomas Aitken and James Nisbet of Fredericton? Nothing is known of their work and in the case of James Nisbet, of his relationship to Thomas Nisbet.

Conclusion

31 Although many questions about Nisbet's life have been answered, much research still needs to be done both in Canada and in Scotland. Many questions remain concerning his early life and training, his business, and particularly concerning the work of contemporary cabinet-makers.

32 A second aspect of this work on Nisbet relates to his furniture. The goal is to photograph and describe in detail labelled and documented pieces. From this, attributions can be made using the criteria of construction techniques known to be used by Nisbet. This will necessitate work on other cabinet-makers of the period, and every effort will be made to find documented pieces so that similarities or differences in construction can be determined.

The author wishes to acknowledge the support and encouragement of his wife Carole, the staff of the New Brunswick Museum Library and Archives, the staff of the Harriet Irving Library at the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, and the staff of the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, especially Dale Cogswell. Special thanks are given to A. Gregg Finley, curator and head of the Department of Canadian History at the New Brunswick Museum.