Furniture / Meubles

Halifax Cabinet-Makers, 1837-1875:

Apprenticeships

Abstract

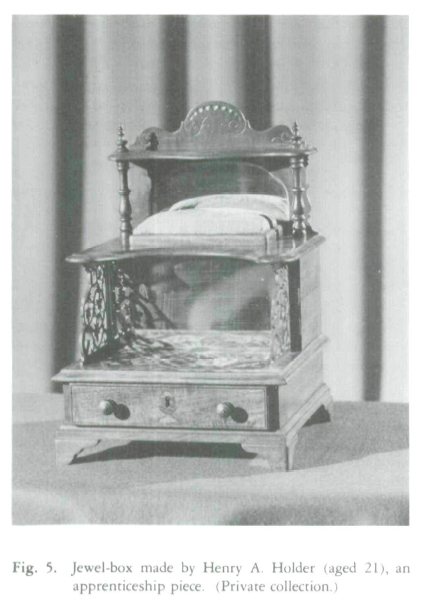

The shops and work of Thomas Cook Holder and Henry Arthur Holder are described and the process of apprenticeship in cabinet-making is discussed.

Résumé

Cette communication, qui décrit les ateliers et le travail de Thomas Cook Holder et de Henry Arthur Holder, étudie l'apprentissage en ébénisterie.

1 The Nova Scotia Museum collections include furniture made or used in the province. The museum also has a card index of Nova Scotia furniture makers and manufacturers with over eight hundred names listed from documentary sources. Yet there is little information about the training of these craftsmen. Recently, five examples of furniture made by Halifax cabinet-makers during their apprenticeships were added to this documentation of Nova Scotia furniture makers, and their acquisition prompted a search for information about this period of a worker's career.

2 Traditionally, cabinet-makers, like other artisans, learned their skills through the apprenticeship system. This system had developed in a context of domestic industry with small-scale workshops, the master often working on his own premises, assisted by his apprentices. As the eighteenth-century handcraft of cabinet-making became the nineteenth-century furniture industry, the opportunity to earn a living as a small independent cabinet-maker diminished and the apprenticeship system also began a slow decline. In the United States "self-sufficient shops capable of turning out a wide variety of products ... disappeared around 1825-1850 with the transition from craft to factory production."1 It was in such small, self-sufficient shops that the traditional technical skills were transmitted during the long apprenticeship period of seven years.

3 A boy usually became an apprentice about the age of fourteen. As an apprentice, he was subject to a written agreement, called an indenture, that defined the separate responsibilities of master and learner. The duration and the conditions of the apprenticeship were specified and the boy's parent or guardian was commonly bound as a third party to the agreement.

4 Few apprenticeship indentures survive in the Public Archives of Nova Scotia and none has been found in the Business Archives of Dalhousie University. Most references to apprenticeships have been found among the records of societies that dealt with poor relief. Some evidence of the status of apprenticeships in Nova Scotia is given in a report by Richard John Uniacke, attorney general of Nova Scotia, when he appeared before the parliamentary select committee on emigration, on 22 March 1826, in London. He stated:

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 25 This placing of poor children under apprenticeships continued as is shown by the records of the Poor House in Halifax for the period 1830-47 when over 300 children, boys and girls, are listed as being sent throughout the province as apprentices. Unfortunately the trades to which they were apprenticed are not given.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 36 Further references to apprentices occur in the 1871 census of Nova Scotia, which lists articled apprentices by county. The total number of apprentices was 131, with six in the city of Halifax; their trades were not specified. Apprenticeships were still being served at the Union Furniture and Merchandise Company in 1880s; the wage agreement book begun 15 March 1882 records items, such as "Bruce Urquart agrees to work 3 years as an apprentice at Painting for $25.00 and board the first year," and "James Fulton agrees in his third year as an apprentice at painting for board and $50.00 and ... to be allowed the privilege of fishing."3 And as late as 1884 an indenture "put, placed and bound George Shaffer aged 5 as an apprentice to a farmer until he shall come to the age of 21 years."4

7 Such scattered references as these to apprentices were found in an archival search. There does not seem to have been a legal requirement in Nova Scotia for apprenticeship papers to be registered with a government agency.5 Those apprenticeship indentures that survive appear to have descended in the family of the original apprentice and are found in family papers. To date only one cabinet-maker's apprenticeship indenture had been located. It is couched in traditional language, conveying a little information about the combination of learning and labour implied in apprenticeship (See note 6).

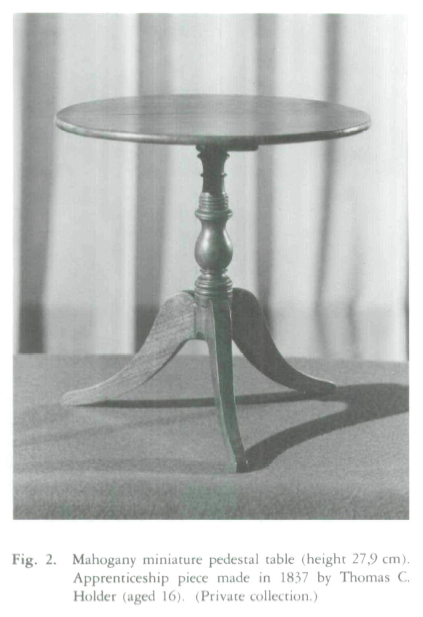

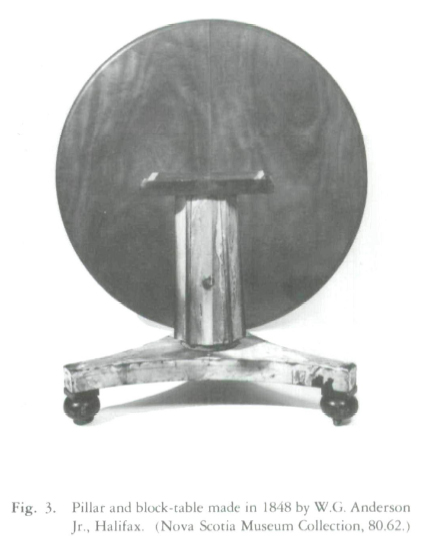

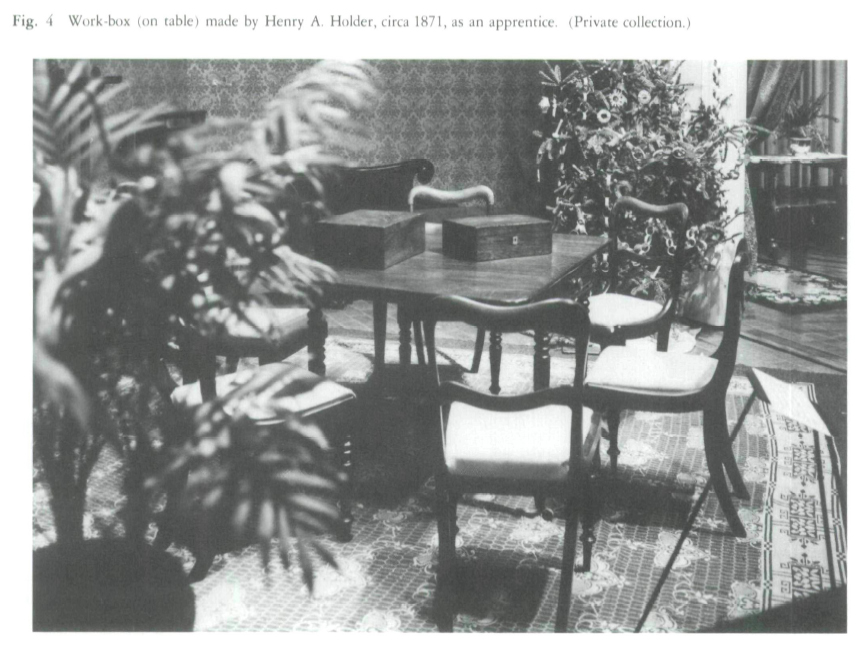

8 The text of the passage referring to Thomas Holder's conduct towards his master is identical to that in an indenture of Wm. Potter of Rhode Island, written in 1716, enjoining obedience and the protection of the master's interests.7 The master for his part is held accountable for the training and welfare of his apprentice, including his board and lodging; in the case of Thomas Holder there was provision made for him to lodge with his mother.

9 The provision of meat, drink, apparel, washing, and lodging is specified in some indentures. At the end of another apprenticeship, a master is "to discharge the said apprentice giving him a full, complete suit of Sunday clothes."8 Sometimes a stipulation about literacy was included in an indenture — the master is "to teach or cause the apprentice to be taught Reading, Writing and Arithmetic as far as the Rule of Three"9 or, as another indenture states "to lern him to read and write."10 In Thomas C. Holder's indentures, the boy's signature is in a clear, well-formed script showing that he had received schooling.

10 An apprentice would begin to acquire some tools during his apprenticeship, and to make his own tool chest may have been an early apprenticeship task. Over one hundred tools of the Holder cabinet-makers' workshop of Halifax survive, mainly of English manufacture. A price list of tools of the period 1821-41 (the James Cam and Marshes and Shepherd Price List of Sheffield, England) shows that two shillings was an average price for a tool; the most expensive one listed was a brace of best quality for nine shillings. (These costs can be compared with the ten shillings paid weekly for Thomas Holder's board and lodging).

11 At the conclusion of the apprenticeship — a date that was specified precisely — the apprentice received his indentures back from his master and was then qualified to work as a journeyman, working for a daily wage or on piece-work until he had enough money to set himself up in his own business, or in partnership. He would continue to make pieces similar to those learned during his apprenticeship, a factor contributing to the long continuance of styles.

12 Of the daily work-pattern of apprenticeship little is recorded. The apprentice learned about materials, methods of construction, forms and proportions, and techniques of decoration by watching, assisting, and participating in his master's work. The apprentice did not receive wages — he paid for his instruction, board, and lodgings with his labour.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 513 Thus the apprentice learned his trade. In the Dictionary of Tools Used in the Woodworking and Allied Trades. 1700-1900, R.A. Salaman states in a note: "I have used the term tradesmen for the men engaged in these trades because that is what they call themselves. The term craftsman' though often used by writers is seldom heard in workshops." The word "trade" derives from "track — a habitual pattern" and in the learning of a trade an apprentice was acquiring a set of traditional skills, a habitual way of doing things, and he learned by looking and listening rather than by reading.

14 The standard apprenticeship training method provoked criticism in England. In The Cabinet-Maker's Assistant published in 1853, the anonymous writer says:

15 The Mechanics' Institutes referred to had been formed first in Glasgow by Dr. George Birkbeck in 1823 to provide general scientific knowledge to mechanics and their apprentices. A Mechanics' Library was founded in Halifax in 1831 and, later that year, a Mechanics' Institute. Fifty volumes were purchased for the library "for the purpose of supplying useful knowledge"; unfortunately the titles of the books are not known It is of interest to note that one of the men who founded the Mechanics' Institute was cabinet-maker James Thomson. Some furniture design books and trade manuals were available in Halifax; two copies of The Cabinet-Maker's Assistant have been found that were owned by Halifax cabinet-makers working in the 1850s and were presumably available to their apprentices to augment their instruction.

16 It appears that little information survives to record the long apprenticeships served by cabinet-makers in Nova Scotia. There are however five documented apprenticeship pieces produced by Halifax cabinet-makers in the period 1837-75. These five examples show either traditional forms or a certain design stylishness that does not have regional attributes. Each piece has some biographical context — the master of each apprentice is known and his work-place — and so they stand as records of local training in cabinet-making. The apprenticeship period shares the anonymity of artisan life; for this reason the survival of these few pieces is worth noting.

in the precence of

Thos. Holder

Elizabeth Holder

William Fraser

Thomas Mackie