Reviews / Comptes rendus

Newfoundland Museum, "Newfoundland Outport Furniture"

1 The Newfoundland Museum has recently begun to experiment with a number of innovative concepts and approaches in presenting various aspects of Newfoundland's history and culture. Its current exhibit of handmade furniture from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, designed by Walter W. Peddle, education officer and associate curator of material history, presents the furniture's cultural importance from two points of view - its current role in Newfoundland outport homes and its potential use as a source of insight into the mental and material worlds of its makers.1 Equipped with firsthand knowledge of local attitudes towards handmade furniture, he has endeavoured to present new ideas and perspectives on it in ways which will be meaningful to local visitors.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

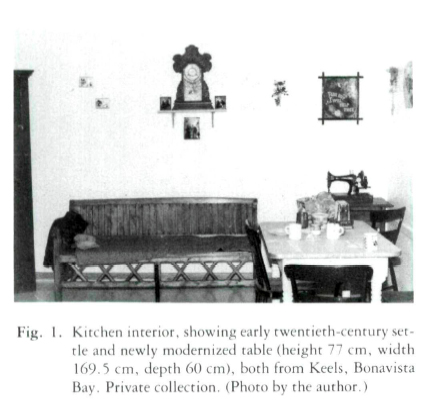

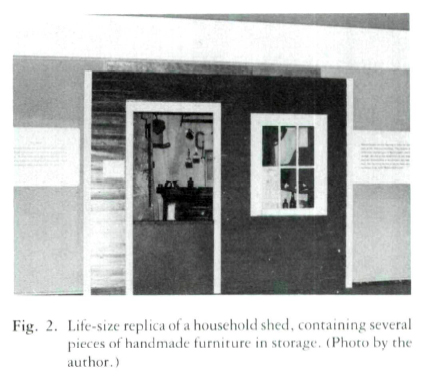

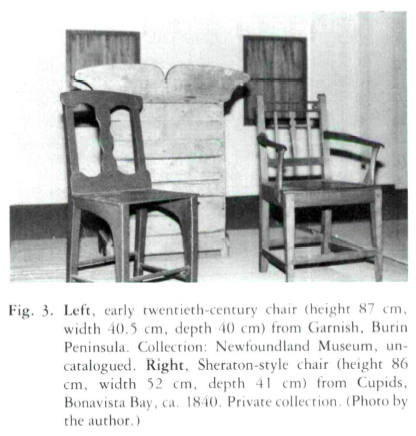

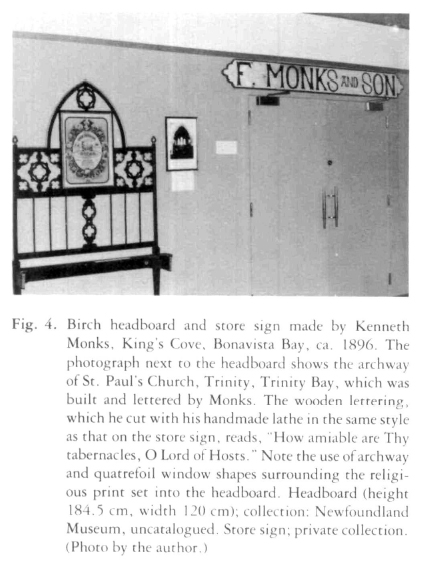

Display large image of Figure 32 To this end he has arranged the furniture in both contextual and abstracted settings within a single exhibit hall. A house interior and shed modelled closely upon those currently found in Keels, Bonavista Bay (where several of the pieces on display were made), provide a view of the furniture's "natural habitat." Here one can see its relationship to manufactured furnishings of various types and ages; to room sizes, shapes, and uses; and to the pillows, pictures, afghans, and knick-knacks that are part of its aesthetic and functional identity today (figs. 1 and 2). A central platform in the exhibit hall displays bureaux, chests of drawers, and chairs from several parts of the province, accompanied by text explaining the regional, individual, and international traits that have influenced the construction and decoration of each piece (fig. 3). Along the wall opposite the house interior, a handmade lathe is displayed along with several articles turned upon it, demonstrating the individual style to be seen in the work of particular craftsmen. With neither the training nor the tools and materials of the cabinet-maker, Newfoundlanders drew upon the versatile skills of boat building and house carpentry to bring considerable imagination and creativity to both methods and design (fig. 4). The exhibit is completed in its contextual dimension by a series of colour photographs of the community and residents of Keels and in its abstracted dimension by a display of the local woods used in furniture construction. The primary, unifying message of the exhibit text is in boldface: its intention is "to demonstrate to rural Newfoundlanders the importance of their handmade furnishings, and encourage them to preserve for present and future generations the remnants of a once rich material heritage."

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 43 Both the aims and the approaches of the exhibit are extraordinary. Normally museums present domestic interiors which are distanced from the audience either in Space or in time; here the local present is on display for local people. This characteristic, along with the current-status of Newfoundland furniture as an artifactual endangered species, links the exhibit closely with the concerns of preservationists of all kinds of vanishing life, from coyotes to Native American cultures to old houses. In the context of the approaches taken by such preservationists, the display of the local present is hardly unusual; it is precisely this which must be brought to public attention it the species in question is to survive. In the context of furniture exhibitions, however, it has seldom been tried before, and the crucial question is, Does it work?

4 Local response to the exhibit, and particularly to the house interior, is complex and difficult to read. Many visitors comment to one another, "Yes, that's the way they looked," or, "I grew up in a house like this one." Parents point out and explain items to their children, detailing their use "in the old days." Many seem confused by the plastic radio sitting on the early nineteenth-century sideboard or the copy of Chatelaine that lies on a mahogany end table in the parlour. Visitors from St. John's, where the museum is located, seem especially unsure whether to view the exhibit as the rural present or the cultural past and visitors from "town" and the outports alike frequently appear to be experiencing both pride and embarrassement as they view the creative handiwork of thirty to a hundred years ago. Canned milk and tea mugs sit on die kitchen table; a string of dried squid and socks is hung above the combined wood and oil stove; traditional accordion music plays softly and seems to come from the radio. Complex emotions play over the faces of visitors. The squid draw smiles and wrinkled noses; the realistically cluttered table brings puzzled looks from adults and children ask if the museum staff has been eating in the exhibit? Text has been held to a minimum to preserve the realism of the home and plastic statuettes, commercial lamps and tables, a crocheted afghan, and family photographs seem to leave visitors uncertain of what items, out of all this sensory richness, they are meant to notice (fig. 5).

5 Newfoundland as a whole has by no means overcome us ambivalence towards the period during which the surviving furniture was made, and this ambivalence has led to the destruction and sale of hundreds of handmade items. That time in its history was one of economic difficulty for many households and furniture was made out of necessity, not choice; commercial furnishings were bought with a sense of celebration in many cases, and the throwing of the spinning-wheel or the old dishes over the cliff was a gesture of liberation from poverty. Many people are still sensitive about Newfoundland's image in the eyes of mainland Canadians, feeling that the province is considered poor, old-fashioned, and isolated. Similar sensitivities are often present between residents of St. John's and the outports. Despite the rapid growth of several other communities, the dispersion of signs of modern urbanity (such as shopping malls) throughout the province, and a rise in mobility which amounts to a cultural revolution, the St. John's "townie" is still for many the embodiment of modernity, and the rural "bayman" the embodiment of traditional life.2 It is no wonder that visitors are uncertain whether to think of the furniture as part of the cultural past or of the rural present; for some it may be too soon emotionally to accept traditional furniture as part of a unified, present-tense, cultural identity. Unfortunately, with a possible oil boom in its imminent future and mainland furniture buyers still gleaning in its outports, Newfoundland cannot postpone an interest in its heritage until ambivalence has given way to nostalgia.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 56 If the exhibit were on display in Ottawa rather than St. John's it would undoubtedly be acclaimed for its creative insights. Here in Newfoundland, though confusing to people who expect to see either the past or the foreign in museums, it will probably receive less verbal acclaim and accomplish more practical good. Here it is seen by people who may still own similar furniture and are thus in a position to affect its survival.

7 The museum could have attempted to idealize the house interior by placing fresh flowers, instead of plain mugs and tinned milk, on the kitchen table, or by setting the furniture off against the gracious background of a wealthy urban home, as might a designer trying to popularize a "country" style of furniture. It could have replaced the smell of dried squid with that of fresh bread and remained just as true to the present realities of Newfoundland outport interiors. It chose instead to leave the chrome edging and masonite top on the handmade pine table, put a container of commercial cleansing powder on the nineteenth-century wash-stand, and let visitors respond as they will. Whether they will respond by sending the picker away empty-handed and keeping their handmade furniture to give to their children, only time will tell.

8 As historian George Ewart Evans pointed out,

It is to be hoped that Newfoundlanders who see the exhibit will be able to use its reflections of past creations in current settings to work with their own sense of heritage — to fill in gaps in children's understanding of Newfoundland's history, perhaps to lend a little balance to some younger adults' conviction that any creation invented out of necessity rather than leisure cannot be "art," or to increase the pride of individuals and families whose homes resemble that displayed in the exhibit.4 In truth, the furniture — in context and abstracted — represents both the cultural past and the rural present, and can serve to illuminate both according to the needs and tastes of the observer.

Special thanks are due to Walter W. Peddle for his gracious assistance in the preparation of this review.