Reviews / Comptes rendus

National Gallery of Canada, "The Comfortable Arts"

1 The roots of "The Comfortable Arts" can be traced back forty years to the donation of a coverlet to the Royal Ontario Museum. This seemingly mundane event marked a turning point for the Textile Department - it was the first coverlet woven in Canada that Dorothy Burnham had ever seen. The arrival of this artifact set in motion, slowly but surely, research into Canadian textile history. Burnham's role in these studies over the years has been a key one. The 1972 publication of 'Keep Me Warm One Night' and the exhibit of the same name at the ROM are both testimony to her involvement in the field. Even though these two works broke new ground, they concentrated only on the Canada to the east of the Ontario-Manitoba border. Several years ago, Burnham contacted the National Gallery of Canada, suggesting that an exhibit be mounted that could survey the whole of the country and, more importantly, explore textiles on a new plane. No longer should textiles in museum collections be of historical interest alone, they should also be considered as art-forms in their own right. The National Gallery gave its encouragement, and "The Comfortable Arts" was finally realized. After Ottawa, it is scheduled to visit the MacDonald-Stewart Art Centre in Guelph, Ontario, from 16 January to 14 February 1982, the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan, from 6 March to 4 April and the Vancouver Centennial Museum from 24 April to 24 May.

2 Burnham chose to structure the exhibit on the work of Canadian ethnic groups, and through this approach she was able to give it a general chronological dimension. The first section focuses on the native peoples, and begins with what seems to be a fur coat composed of rabbit pelts. In actual fact, the coat was produced from long strips of fur twisted into cords which were then looped to form a quite dense textile. This technique is well illustrated by a simple schematic diagram accompanying the text of the display. Similar small drawings were prepared for a number of artifacts in the collection and are much more effective than written descriptions alone in clarifying the making of the fabrics. Native textiles are further illustrated by snowshoes, bags, and a number of blankets. A series of woven and beaded belts forms the second section and creates a bridge to the next ethnic group, the French Canadians. The organization of the braided work into a separate section, however, seems unnecessary. There are numerous instances in which similar overlaps in textile techniques transcend ethnic lines, so this special grouping is not justifiable.

3 In the third section, French Canadian products are spotlighted. As with all the other groupings, there is no consideration of chronology within their arrangement. A number of coverlets of weft-loop or boutonné weaving, some skirts, shawls, and a man's work shirt make up the bulk of the French selection. One of the highlights here is a handwoven and hand-embroidered altar cloth, which is effectively mounted as the final piece. The Loyalist traditions comprise the fourth section. Linens are displayed, as well as the predictable blue and white coverlets of summer and winter weave and doublecloth. The Scottish, Irish, Irish, and English textiles follow. Again, coverlets abound. As in some of the other sections, a number of spinning and weaving tools are included here. Of particular interest are two weavers' pattern draft, which are indeed rare documents. The selection of clothing is particularly well chosen; a striking piece is the rough, bulky, girl's dress, noteworthy because so few are extant. The German section, the next area, is largely made up of coverlets. Finally, the exhibit ends with a catch-all collection representing the multi-cultural traditions in western Canada. Attention focuses on Icelandic, Ukrainian, and Hutterite work. Of note is a tape for tying a baby, as well as more clothing, floor coverings, and blankets. The exhibit closes with a colourful, intricate Doukhobor woven rug.

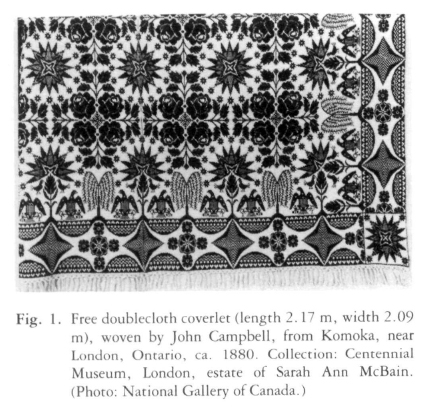

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 In terms of display methods, the exhibit is mounted with a certain eye for colour and texture. The coverlets, which in the Loyalist period were so often blue and white, have at least been chosen with a consideration for contrasting patterns. The question of colour is especially important in the Doukhobor selections. The bright hues here suggest a tremendous cultural distance between that group and the more staid Loyalists. Appreciation of textures has also been well handled. The coverlets again illustrate this. They are not encased behind glass barriers, but instead are hung in tantalizing folds. The temptation to stretch out a hand and touch is almost too powerful to resist. Most laudable is the choice of textile products displayed. Bed and table coverings, sashes, and some striking pieces of clothing make up the bulk of the exhibit and provide good variety in forms. The addition of such artifacts as a hybrid Scottish-French horse blanket was a delightful inspiration, even though it has been incorporated incorrectly into the German textile section. The whole exhibit is arranged before a backdrop of simple wooden planking, which seems practical for dismantling and shipping to new display locations and helps to soften the stark white gallery walls.

5 In spite of these commendable points, there are some flaws in the physical presentation of the exhibit. For instance, the sign that identifies the section dealing with Indian and French braiding is mounted on the far side of the wall on which the artifacts are displayed, and the wall itself is positioned in such a way that it is easy to miss the sign altogether. The identification of the French Canadian section as the third division is then confusing. The linkage between other sections is also clumsy. The English and German traditions do not flow smoothly from one to the other, and in general more attention should have been paid to the ease of movement through the exhibit. There are also similar difficulties within each section. For example, Samuel Fry is mentioned several times before any basic biographical information on him is provided. In the last section, which deals with the "other" ethnic groups, some descriptions of Ukrainian artifacts are placed before the general commentary. To a visitor who is carefully following the story-line of "The Comfortable Arts," this positioning is quite frustrating.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 26 In fact, the entire exhibit could be much improved with different display techniques. Although Burnham's concept of the textile as both a functional object and an aesthetically pleasing creation is novel, the exhibit does not differ in appearance from a conventional historical survey of fabric development. Her message is apparent only in the text posted on the exhibit room walls and recorded in the catalogue and the fact that the building housing the display is an art gallery. Many of the artifacts are suitably presented tor the purposes of an informative textile collection, but there is an overall lack of drama to transcend simple museum mechanics. One wonders if perhaps the exhibit should not have consisted of fewer artifacts, which could have been studied in greater isolation and discussed with more individual attention. This simple technique could have been copied from the normal approach of an art gallery, where art works are not gathered so closely together, and it might have stimulated mote reflection on the part of the visitor.

7 Finally, also to be questioned is the decision to omit the contemporary crafts revival in the context of" textile production. Burnham does note that the intent of the exhibit was to focus on those materials produced in a pioneer society, where self-sufficiency was a necessity. Nonetheless, the collection includes some artifacts that do not seem to fit this criterion, for instance, handmade man's shirt made in rural Quebec circa 1900 and a sweater and bonnet from Alberta in the 1930s. In the case of the latter, the catalogue clearly states that the handspinning of the wool was done more as a hobby than from necessity. Indeed, had some example of recent craftwork been incorporated, they could have provided an eloquent contrast in visual terms and underscored the fundamental shift in the significance of handwoven textiles in Canadian society. One must admit, however, that given the wide range of artifacts considered for this exhibit, there were good practical reasons for the exclusion of recent work.

8 The catalogue for "The Comfortable Arts" has much to offer both layman and researcher alike. It is clearly written and admirably illustrated. The diagrams of the structure of certain textiles that are so helpful in the exhibit ate included along with the brief descriptions. The photographs have been well reproduced, and it is pleasing to see in the photographs of the clothing that it is placed on supports, as m the exhibit, to make its style more obvious. For those with more than a superficial interest m Canadian textile-history, Burnham also includes a bibliography. The acquisition of the catalogue as a source-book and as a guide to an innovative project is recommended.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 39 In summary, "The Comfortable Arts," its shortcomings notwithstanding, marks yet another promising development in the expanding horizons of Canadian material history. The perception of artifacts as indicators of a society's activities and aspirations has been reaffirmed. Burnham's own words provide a fitting comment on the significance of the exhibit.