Research Notes / Notes de recherche

Company Housing in Wabana, Bell Island, Newfoundland*

1 Atlantic Canada's landscape has been shaped not only by farmers and fishermen but also by the mining corporations.1 Most material culture research in Atlantic Canada, however, focuses on pre-industrial remains of rural and outport areas.2 This research note describes my examination in 1980 of company housing of Wabana, Bell Island.

2 Bell Island is located in Conception Bay, approximately twelve miles from St. John's. This island still bears marks of fishing and farming activity, but the arrival of iron-ore mining companies in the late nineteenth century greatly altered the look of the land. Mining officials first visited the island in 1893: "the north side of the island was heavily timbered with fir trees, and to find one's way it was necessary to make use of a compass, the south side was dotted at intervals by primitive farms. " By the early twentieth century, "the quiet peace of the silent forest has given place to the noises and bustle incidental to the operation of a great industry; while the nearby untenanted wilderness has become a populated centre of activity."3

3 The red sandstone that caused this massive development had been noted by geologist J. B. Jukes in 1840, but its value was not realized until 1892 when the rocks were identified as hematite.4 The Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company bought property on the island in 1893, began open-pit mining in 1894, and shipped its first cargo of iron ore in 1895.5 In 1899 this company sold part of its property to Dominion Iron and Steel Company which also commenced open-pit mining.6 Underground mining started early in the twentieth century.

4 Bunkhouses were the earliest form of accommodation supplied by the mining companies, but between 1901 and 1911 a so-called "mining boom" occurred, the population more than doubled, and the companies provided housing for workers and their families.7 During this decade, Wabana emerged as a community whose housing was controlled by the companies. In 1907, according to one report, the "Scotia company" had 500 men working for $1.35 a day, less 20 cents for lodging supplied by the company.8 Sources reveal little about the design and construction of the houses, however; more information is obtained by examining the landscape of the island and talking to present-day inhabitants.

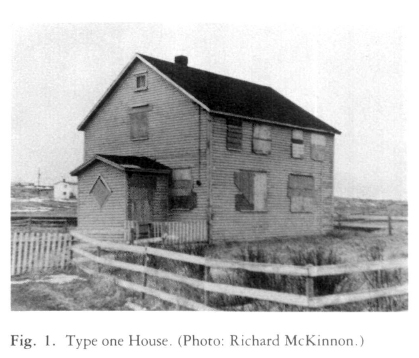

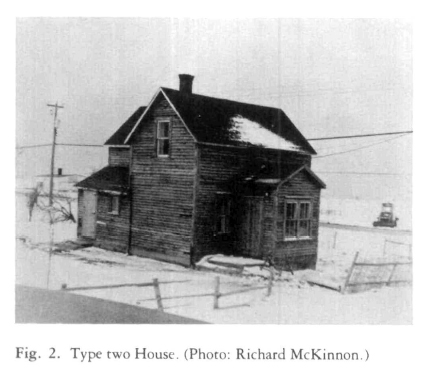

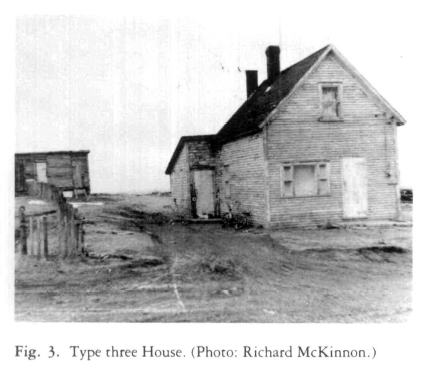

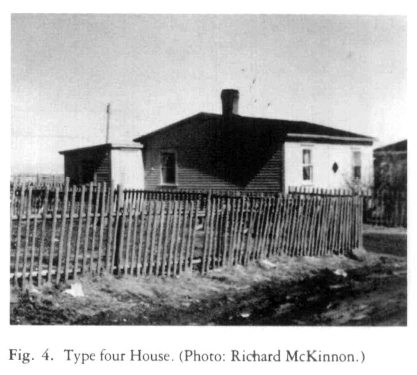

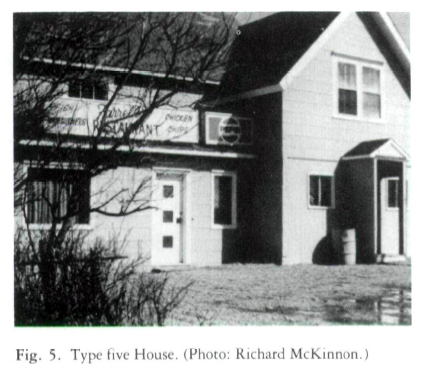

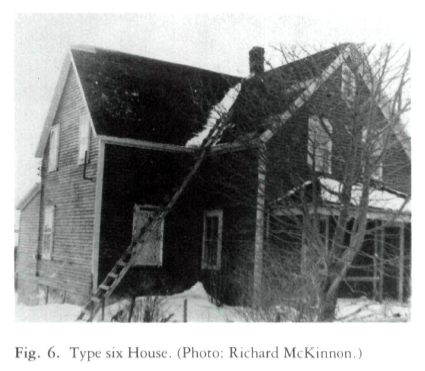

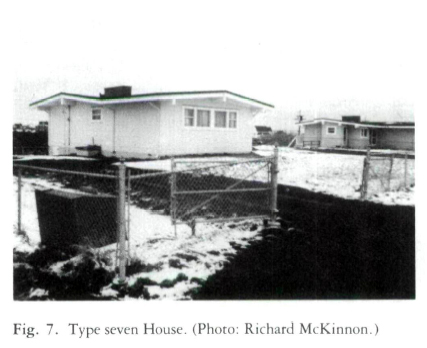

5 There are seven different types of company houses still standing on Bell Island. Types one to four can be categorized as worker's housing; five, supervisor housing; six, "bridal" housing; and seven, management housing (figs. 1-7). This classification system is based not only on the status of residents, but also on floor plans, the nature of construction, roof designs, and exterior details.

6 The oldest type of company house still standing, according to oral tradition, is type one. The only one of this kind remaining is near "Scotia Number One," the earliest mine site in Wabana (fig. 1), and is two storeys high, two rooms wide, and one room deep. The front façade has two windows symmetrically placed on the first floor and two directly above on the second. Windows at the back of the house do not conform exactly with the front façade. This house is larger than other family dwellings on the island and it probably served as one of the bunkhouses frequently mentioned in early newspaper accounts. Because of a recent fire, however, the interior of the house could not be analyzed or this hypothesis confirmed.

7 The house illustrated in figure 2 is one of the most common types of workers' houses in Wabana. One and one-half storeys high, it is one room wide and two rooms deep with an integral addition at the back. The symmetrical façade has a central doorway separating the two windows; in some cases porches have been added. One resident termed this house the "saddlebag house" because of the way the main roof ridge attaches to the addition. A unique characteristic of these houses are the supplementary additions often found on the integral back addition, sometimes on each side of the back addition, sometimes on only one side.

8 While the façades of house types one and two face the street, the gable ends of type three face the street (fig. 3). The front door is located on the gable end and the back door is found on the long side of the house. These houses are one room wide, two rooms deep and one and one-half storeys high. According to oral tradition, front porches and back additions were added at a later date, and some of the houses are decorated with wave-like cut clapboard under the gable eve facing the road.

9 Type four houses are only one storey in height and resemble the ubiquitous bungalow found throughout North America (fig. 4). It is difficult to pinpoint the original location of these houses because many were moved after being constructed. Only a few remain near the former mine sites, yet, upon close examination, each of these houses are similar in floor plan and size.

10 Type five houses (which I have termed supervisor housing) are called staff houses by Bell Island residents (fig. 5). Only three are still standing and the name and size of these houses indicate that managers and supervisors were residents. Two storeys in height, they have two chimneys and a large integral side addition. Like houses of type three, the gable ends face the street. Cosmetic changes have frequently been made to these houses: picture windows and aluminum framed windows have been added, original clapboard siding has been replaced with vinyl and aluminum siding, and porches have been added.

11 Type six houses are similar in size, floor plan and exterior decoration to type five, but they have a different function. Bell Island residents call these structures "bridal houses" because they were originally constructed to be used by newlyweds on their honeymoon.9 Constructed in 1911, only three are still standing on Bridal Street.

12 Type seven houses are located in an area known locally as Snob Hill (fig. 7).10 These houses were prefabricated in Montreal and shipped to Bell Island in the 1950s for the use of mine managers and they contrast sharply with the other company houses. By locating these houses on a hill overlooking the mine sites and segregating them from the established homes, management consciously delineated the difference between the average worker and mine management.

13 Types two and three houses are the most numerous of company houses still standing on Bell Island. A close examination of each type follows. The type two house which was studied is located on Grammar Street in the area known as the Ridge. This house is 24 feet by 25 feet in size, and the ground floor derives from the two-room hall and parlour plan. A bathroom, porch, pantry, resting room, and storage area were added later. The back door, which is used most frequently, opens into a small porch (6 feet by 4% feet) leading directly into the kitchen. This small kitchen sees much of the daily activity and can be termed the public room of the house.11 A day-bed next to the stove is in constant use by residents and visitors. A small pantry (5% feet by 4 1/4 feet), once part of the kitchen, is located next to it. In addition to providing storage space, this room provides the wife with a private area.12

14 What I have called the "resting room" (because of its function) separates the kitchen and parlour. The furniture in this small room (12 feet by 7 feet) consists of a day-bed, bureau, and clothes rack. Smaller than the kitchen daybed, this day-bed is used sparingly by residents when no visitors are present or by overnight guests. This room was originally part of the parlour, and no door separates the two. Only special visitors, clergy or unfamiliar guests, are invited into the parlour. Family photographs, religious pictures, and souvenirs are found on the walls. Even though this room is the largest in the house (13 feet by 12 feet), it is seldom used. A door on the far wall of the parlour leads into the porch, which is primarily reserved for storage. The front door facing the street is seldom used; indeed in many houses it is nailed shut. (Even today, in many Newfoundland outports, new Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation houses are built with no steps leading to the front door.)

15 The upstairs consists of three small bedrooms and a crawl space.13 One bedroom functions as a guest room in summer and is closed off in winter. One bedroom is used as storage and the other is used year round by the inhabitants. Originally, occupants of many of these houses included boarders as well as family members. The large bedroom is heated by a small hole in the floor which allows heat to enter from the kitchen. Religious statues and family photographs ornament the bedrooms.

16 Major changes were made to this house in the recent past. In the late 1950s a bathroom was added to the kitchen. Until this time outhouses were used. New modern sliding windows have replaced the older four-paned windows in the kitchen and bedrooms.

17 The type three house examined has a two-room hall and parlour floor plan with a back and side addition. A front porch, back porch, bathroom, and side addition were built later. The back door opens into a porch (10 feet by 7 feet) used for storing clothing, buckets, and cooking utensils and leading to the kitchen, the largest room in the house (14 feet by 14 feet). The oil stove is attached to a chimney on the central wall. Like house type two, residents and guests enter the house by the back door. A side addition was constructed in the late 1950s when a bedroom was needed, and this room is now a dining-room. Family photographs and religious prints adorn the sideboard and walls.

18 A square hole in the kitchen/parlour wall originally heated the parlour. At present, an oil floor heater is used. The furniture consists of a couch, cot, chairs, and sideboard. In this house, the parlour is frequently used because residents close the upstairs rooms and sleep there during winter.14 In the past, however, it was only used for special guests.

19 The housing in Wabana reveals that the mining companies dominated this industrial landscape. Some of the streets are laid out in a grid pattern, workers' houses are located as close as possible to the mines, and supervisors' and managers' houses overlook the mine sites from hills. Supervisors and managers are provided with larger and more modern houses than the workers. Even though the Bell Island workers were forced to reside in house forms alien to their cultural background, they articulated their cultural ideas in various ways. The non-use of front doors, the small garden plots, the constantly used kitchens and seldom used parlours, and the numerous religious ornaments within the houses display the influence of traditional rural culture on this industrial community. The various alterations and additions demonstrate that Bell Island residents wanted to keep abreast of new advances in building techniques. They did not want to be viewed as old-fashioned or traditional.

20 Only by further work on the island, combined with an investigation into possible housing antecedents in Nova Scotia and New England, can a better understanding be obtained of some of the more complex cultural and humanistic aspects of industrial development.15

* This paper was originally prepared for a graduate course in vernacular architecture taught by Dr. Gerald Pocius, Memorial University of Newfoundland, in 1980.