Research Notes / Notes de recherche

Costume Research and Reproduction at Louisbourg

Forward

1 This is a condensation of the introductory chapter to a comprehensive study of costume research and reproduction at the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park. Maria Razzolini, historical researcher with Parks Canada, worked with Florence MacIntyre, curator of textiles at Louisbourg, for eight months compiling and analyzing the research and design information accumulated since 1969. More than thirty different types of eighteenth-century civilian and military costumes have been reproduced at Louisbourg, and the larger study includes a full description and technical analysis of each. It is replete with line drawings, water-colour illustrations, pattern sketches, and technical notes and also includes a twenty-seven-page bibliography of sources used. This bibliography has been placed on file at the History Division of the National Museum of Man and in the Fortress of Louisbourg Library.

2 Manuscript reports by Louisbourg staff, including the first draft of the costume study, are also available for research at the Fortress of Louisbourg Library. A list of those published by Parks Canada is available from the Historical Records Supervisor, Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park, P.O. Box 160, Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, B0A 1M0.

3 Throughout time, one of the most visible manifestations of human culture has been costume. In recent years this particular aspect of material history has been given serious attention by Parks Canada through the increasing use of animation programmes as important interpretative tools. One of the most ambitious and varied reproduction costume programmes is that in operation at the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Park, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Here a stunning means of portraying eighteenth-century Louisbourg has been devised, and an invaluable source for the study of French costume and culture has been created as well.

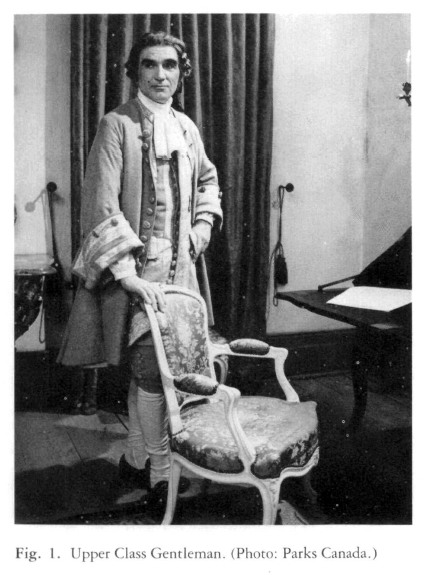

4 Fashions of any kind are in general set by the upper echelons and then copied according to resources. The fashions of a people and a time reflect the society, and at Louisbourg, fashions were moulded by the influences of the Old World and the New. Eighteenth-century Europe was dominated by the French. French fashions and tastes were widely copied, and the French language was predominant in Europe, especially among the nobility and in diplomacy and the arts. In France, within the rigidly structured three estates of the ancien régime, everyone expended much time and effort emphasizing differences in dress, deportment, dining, and so on, giving rise to classes within classes. The costumes and behaviour of a particular group reflected its members' affluence and aspirations. As France colonized North America, attempts were made to transplant familiar aspects of life to New World settings. In cultural and social terms, the Louisbourg colony was patterned on the mother country, yet the colonists' life revealed the definite influence of the New World. The heavy commercial orientation of Louisbourg, combined with the absence of any higher clergy and the relatively small numbers of lesser nobility, fostered a more open society in which people of wealth and birth attained equal social status and often intermarried. Yet the élite of colonial society shared the same desire for status and ability to display proper ranks that characterized their counterparts in France. With the basics of the class system preserved, the various aspects of a person's costume still indicated the level of society in which he or she moved or aspired to move.

5 This structure of society, class, and behaviour formed the framework within which costume and its accessories and manners functioned. Using this information as a base, the difficult and complex business of piecing together the Louisbourg garments of the 1740s, the years chosen for animation, commenced. As with all such ambitious, ongoing projects, the Louisbourg costume programme has involved a considerable number of people in the research effort. Preliminary work began in the 1960s on military uniforms. Marcel P. Baldet was contracted to conduct research and archival searches in Paris on those regiments that served in the colonial town. This resulted in a number of short but concise reports accompanied by copies of army regulations and contemporary descriptions, plus samples of eighteenth-century fabrics and military livery lace. Historian Victor Suthren, working with the archaeological and artifact collections staff, produced an analysis of artifacts taken from the site excavations, which quickly evolved into a series of design portfolios covering shoes, powder horns, haversacks, and cartridge boxes. The artifact collection also yielded a number of buttons and buckles to serve as a basis for reproduction. René Chartrand, military curator with Parks Canada in Ottawa, and his associate, Eugene Leliepvre, military costume illustrator, contributed additional experience and expertise.

6 The costume animation programme began formally in 1969-70 when costume designer Robert Doyle (now with Halifax's Neptune Theatre) was contracted for a year to initiate costume production. By the time Doyle arrived, the researchers and consultants involved had accumulated sufficient information to permit production of the first military costumes, and in 1971 historian Gilles Proulx produced an in-depth examination of the primary documents in "Étude sur le costume militaire à Louisbourg, 1713-1758." Doyle turned his attention to research into civilian costume and wrote a short general survey of eighteenth-century dress entitled, "A Report on Civil French Costume at Louisbourg, 1720-1745" (1969). At the same time he trained a staff of three to weave reproduction textiles and to copy period garments using eighteenth-century tailoring techniques. He also began to acquire commercial textiles and accessories acceptable to the costume programme's exacting standards, and he designed and supervised the production of nine complete costumes (two male, seven female), plus an assortment of extra pieces.

7 After Doyle's departure, the costume unit came under the direction of costume designer Florence MacIntyre, who is responsible for all designs after August 1971. Together with cutter/seamstress Greta Beaver and weaver/ seamstress Edith MacIntyre, Florence MacIntyre has produced over two hundred costumes and collected many accessories. They too have worked closely with the historical researchers. Monique La Grenade continued the work into civilian costume begun by Doyle and produced several comprehensive reports in the early 1970s: "Le costume civil à Louisbourg: 1713-1758 - Le costume féminin" (1971); "Le costume masculin" (1972); "Le costume des enfants" (1973).

8 Because French law forbade the weaving of cloth in the colony as a manufacture, fabrics like most supplies were imported, and the populace, drawing upon Louisbourg's role as a trading centre, managed to keep reasonably abreast of current fashions in both garments and textiles. Textile research expanded with Gilles Proulx's "Recherche en France, 1er volume" (1974). Reproduction uniform cloth, designed from antique samples borrowed from France, was woven initially in the Louisbourg Costume Department, but as the weaving programme expanded into the area of civilian clothing the military material was contracted out to a private manufacturer who still produces the fabric — designated "Louisbourg" — according to precise specifications. Further information was gleaned from the artifact collection, with the analysis, advice, and assistance of the Royal Ontario Museum. Research in the Maurepas Collection of the Winterthur Museum in Delaware revealed valuable data concerning the colours, textures, compositions, and thread counts essential for accurate fabric reproduction. In all cases, preliminary research, using estate inventories, import lists, government records, civilian papers, artifact and antique collections, was supported by secondary sources, and work in the Louisbourg Material Research Picture File, a repository of over 5,000 prints and photographs of sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century works of art. Especially useful have been the creations of Boucher, Chardin, the Le Nains, Longhi, Vernet, and Watteau. In addition, both general and detailed research has been done by many others; for example, Robert J. Morgan provided background information for the wearing and production of costume; Denise LeBlanc conducted research in France for a report on middle-class manners and gathered information and practical experience on bobbin- or pillow-lace. Other researchers wrote brief descriptions of specific garments, military accoutrements, and costume livery. The result has been the collection of Louisbourg reproduction garments described below.

9 With the ascendency of the child-king Louis Ⅴ in 1715, rigid court discipline relaxed, and so did female dress. As formal court occasions lessened in number, women adopted looser, more comfortable garments. This development gave birth to the dress most typical of the eighteenth century — the sack (saque) or robe à la française — the gown so predominant in the paintings of Watteau. It was derived from the late seventeenth-century mantua and originally meant for negligee wear; by the 1740s its casual look had been formalized into a basic dress of general use and widespread appeal. The long box-pleated back hung loose and flowed into a train. (A variation on this style, popular in England and adhering more closely to the original seventeenth-century mantua designs, was the robe à l'anglaise in which the pleating was stitched down to provide a close fit.) Always worn over the compulsory stays, it hung open in front to display a petticoat and stomacher of matching or suitably contrasting material. It was sometimes fastened with a row of bows known as an échelle, with matching bows at the elbow. The sleeves had either small cuffs and were pleated on the inside of the elbow to accommodate the bend of the arm or finished with from one to three flounces, cut "triangularly" to hang long over the elbow but short inside in the bend of the arm., A wedge of radiating pleats at the hips allowed for the round, elongated sides of the pannier, which in the France of the 1740s was kidney-shaped and usually worn resting on small, half-moon pillows called hip-pads, tied on around the waist with tapes.

10 Petticoats were straight cut, utilizing a fullness pleated into the waist to accommodate the pannier, rather than gored. Those meant for display were often embroidered or quilted. Underneath the whole, women wore a chemise, the basic garment of fine cotton, linen, or silk worn next to the skin night and day. Reaching almost to the ankles, it had elbow or wrist-length sleeves, gathered into frills, and a drawstring, self-frill neck; the ruffles at both neck and sleeve ends were trimmed with delicate lace. Long aprons of fine sheer fabrics, frilled and ribboned caps, and lace-edged neckerchiefs were usually worn in the mornings and afternoons at home. Wide flat straw hats and/or parasols also constituted popular daytime accessories, since preservation of a fair complexion was of utmost importance. Stockings were usually silk and were often worked or embroidered, as were the high-heeled shoes and mules of fine fabrics and leathers. Female riding-habits were patterned after male attire with vest, jacket, tricorne, and full skirt worn over a special riding hoop. Bias-cut or circular capes or cloaks with hoods gave adequate cover in cold or foul weather, and simple wraps were worn in fine weather. Accessories such as gloves, muffs, separate pockets, and an early form of reticule found occasional use.

11 Since the 1600s the French had been the leading manufacturers of all luxury dress items - silks, velvets, brocades, damasks, metallic braids, laces, and so on. The new era of enlightenment and reason responded enthusiastically to the Arcadian movement's emphasis on nature and simplicity and the influence of oriental culture. The heavy formal brocades of the late seventeenth century gave way to the magnificent silks of flowing lines, delightful colours, and dancing designs of the Rococo period. The exquisite silks of the period made further adornment superfluous, as the heavy but crisp fabrics fell into perfect folds. Pastels were favoured and stripe, flower, feather, ribbon, scroll, shell, and lace motifs, as well as eastern themes, constituted popular designs. Materials were often worked in coloured silk embroidery as well. Beautiful laces, such as Brussels, Mechlin, and Valenciennes, were widely used, as was additional embroidery in coloured silks and metallic threads.

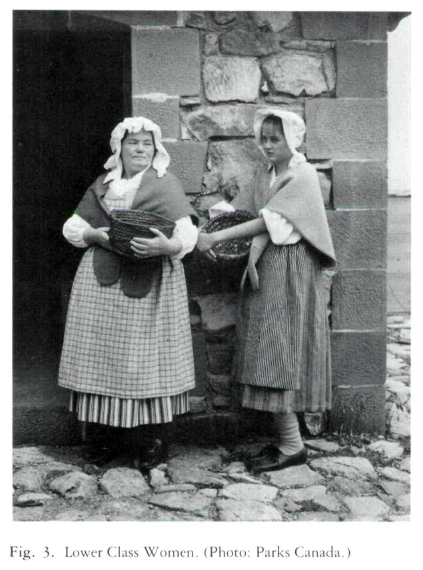

12 In keeping with this simplicity, jewellery and other related adornments remained uncomplicated. Real flowers, ribbon chokers, some with crosses or pendants, and ribbon bracelets, were favoured, although precious stones, especially diamonds set in silver, were worn by anyone with sufficient resources. Pearls, popular for centuries, were widely used in chokers, necklaces, bracelets, brooches, earrings, and hair ornaments. Court dress retained its elaborateness, abounding in gold and silver laces and embroidery, often still using the heavily-boned court bodice with its low, oval neckline. At court, jewellery was worn as lavishly as one's circumstances allowed. Especially popular was the parure - a matching set of necklaces, bracelets, earrings, stomacher pieces, and hair ornaments.

13 The conception of ancient Greek and Roman white marble statuary as the ideal of loveliness made a fair complexion highly fashionable. Both men and women used make-up, and the desire to achieve the proper degree of whiteness encouraged a widespread use of powdered white lead, especially for evening wear, despite the dangers of poisoning. By the eighteenth century beauty marks, deliberate flaws placed to emphasize particular features of beauty which had originally been used to cover smallpox scars, had become elaborated into shapes cut out of black and ted taffeta or leather, capable of conveying messages through their shape and position. Hair was worn fairly short and powdered and set in simple styles, usually swept back from the forehead and curled at the back of the head.

14 The middle and lower classes copied the fashions of the day but used fabrics which, by being more serviceable and darker in colour, proved better able to withstand soiling and the strains of physical exertion. The chemise was plain, having loose or cuffed sleeves to the elbow or wrist. Panniers made relatively infrequent appearances, with preference reserved for gathered skirts over a number of plain or flounced petticoats. Firm corseting achieved the straight look of the eighteenth century in both sexes, women being more bound to this fashion restriction than men. For females, heavily boned corsets or boned jackets constituted standard wear for all classes. The jackets had short skirts as a rule and were laced with a cord in front, often over a stomacher. The matching or suitably contrasting skirts were gathered at the waist. Horizontal border and vertical stripes and small patterns and checks found general favour - usually woven in rich, basic tones. Fabrics were composed of organically dyed linen, cotton, and wool, with silk when and where possible, or paired blends of these natural fibres — a practice which created a wide variety of weights and textures. Necessities for a respectable appearance included a white bonnet and neckerchief, as well as an apron - white for the more well-to-do, coloured for the labourers. Shoes and mules were of leather, with buckles or ties and high or low heels; stockings were of wool or wool blends. Workers out-of-doors favoured wooden shoes or sabots. Capes, cloaks, and wraps were worn in inclement weather, as were muffs, scarves, and half-hand gloves. Adornment included embroidery and lace when possible, real flowers and ribbons, the latter used as chokers, necklaces, and bracelets, sometimes with a hanging cross or pendant. Make-up was rarely worn, although lotions and soaps, most made in the home, found widespread use. Little girls wore smaller versions of adult female garments.

15 Garments for both sexes were tailored to suit the contours of the body, the dart not yet being in common use. This was especially noticeable in male clothing. Originally the coat or justaucorps was fairly simple, the front and back being each in two pieces with the straight side seams stitched to just below the waistline. The rest of the skirt remained open to accommodate the sword - the hilt passed through the side vent and the blade through the back vent. The coat was collarless and had cuffed sleeves. By the 1740s this design had been modified by providing extra width at the sides and by using an arrangement of pleats over the hips, gathered just below the waistline where the side seams ended. Also the fronts and backs were swung off the straight of the material, the bias cut giving extra pleats at centre back and sides to improve the fit and hang of the garment. The sleeve cut was curved to accommodate the bending of the arm, with the top seam at the back of the shoulder. The sleeve was fitted to the elbow and had deep cuffs fastened into position by buttons. Similar coats were made for outdoor wear; while of a looser cut, they adhered to the same design but sometimes had a collar. Coars were usually buttoned with only four buttons at the waist.

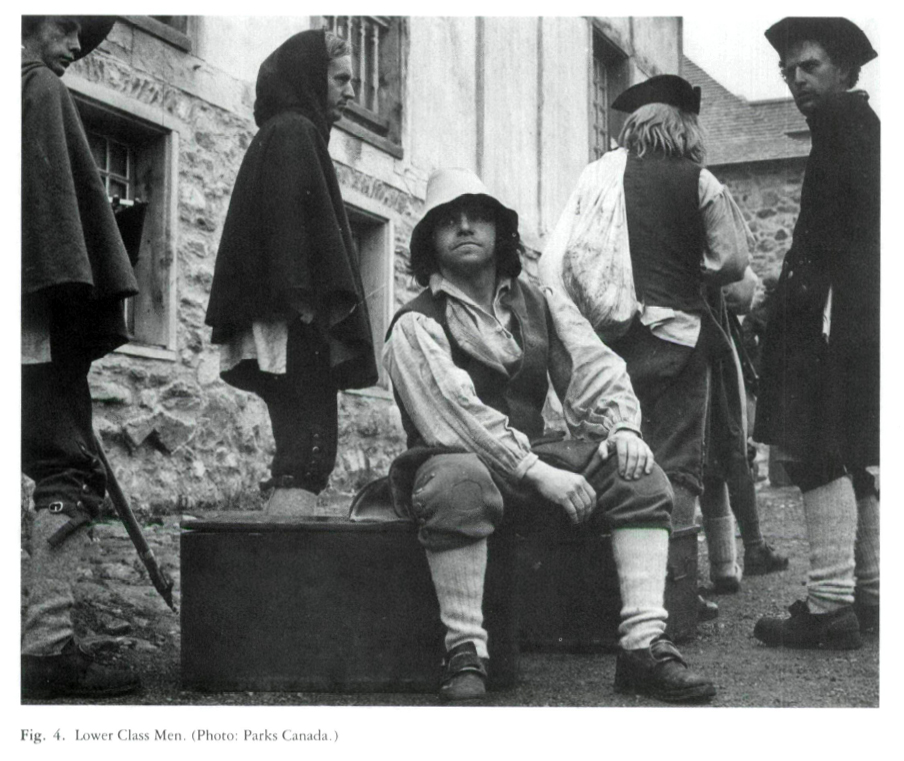

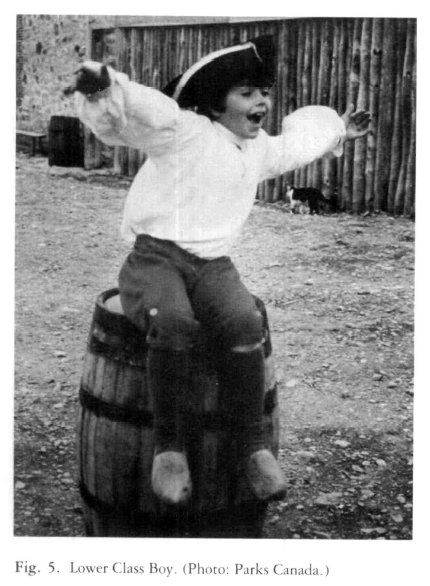

16 The vest cut followed that of the coat, but held to the straight of the material and was narrower and not pleated in the skirts. It could have sleeves or not, and was usually worn undone at the top to display the lace of the jabot. Both vests and coats had buttons and buttonholes, often ornamented or frogged. Decoration ran down centre' fronts, round the pockets, down the centre back from the waist, on pockets and cuffs, and was often woven into position on coat lengths. The breeches, almost hidden under the rolled stockings, vest, and coat of the 1740s, were cut for comfort rather than style. The backs were full-cut and adjustable at the waist. The garments had a front fly and were cuffed at the knee and fastened therewith buttons and a buckle. Coat and breeches were usually of the same fabric, with a matching or suitably contrasting vest, although this did not constitute a rigid rule. Heavily embroidered cloth of fine quality found equal favour to the stiff, figured silks woven with small, all-over designs which were made especially for these suits. Court dress was more elaborate, with heavy metallic or coloured embroidery and gold and silver lace.

17 Although some men preferred coloured hose marching their suits, stockings were usually white and could be tucked under the breeches cuff, or, more commonly, rolled over the knee on top. As underwear men wore a straight-cut chemise with stand-up collar, front button closure, and long sleeves gathered into buttoned and frilled wrist cuffs, sometimes trimmed with lace. A stock was wound around the neck over the chemise collar. Footwear included high-heeled, buckled shoes of fine leather, heavy boots for riding or hunting, and soft slippers in the Eastern tradition for undress. For casual wear at home, long, flowing, brocade robes with matching turbans or capes were popular. For travelling or bad weather, capes provided adequate protection, as did long, loose overcoats called greatcoats; the latter sometimes had a collar or shoulder cape and were either single- or double-breasted. Common headgear remained the black tricorne, often trimmed with lace, ribbon, or plumes. Scarves and gloves were used occasionally. The focus on simplicity limited jewellery to rings and small brooches or pins as a rule, although make-up was worn lavishly, especially in the evening. Hair was long, curled at the sides, and gathered at the back by a ribbon. There was such a profusion of elaborate styles that wigs predominated.

18 In the middle and lower classes this style was as closely adhered to as resources permitted, with the fashionable skirt flair proportioned to signify the degree of class and money. The need for greater mobility and the high cost of fashionable tailors induced these classes to favour garments of simpler cut, the coats often having few or no pleats. At the lower levels, coats came in variable lengths, and usually had wide, unshaped backs. Shoes were low heeled with buckles or ties. Tricornes possessed simple cord trim. Little boys wore skirts until the age of about five; once fitted with breeches, they wore smaller versions of adult male garments.

19 In terms of fashion the uniforms of the French military were patterned closely on ordinary civilian male garb. Quality and fit varied with one's resources just as the width of the justaucorps skirt signified position. High-ranking officers preferred their uniforms custom-made of the finest materials. The common soldiers bought their clothes from the government or their commander and made do with poorer quality. The distinguishing military aspects of the uniform remained the regimental colours and the rank insignia.

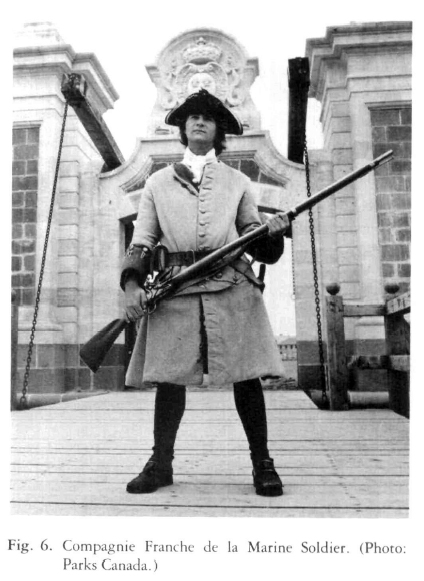

20 The most predominant group in Louisbourg in the 1740s was the Compagnies franches de la Marine, the military wing of the Department of the Marine which was responsible for ships, ports, and colonies. They received their clothing in two instalments: the grand habillement in the first year, consisting of justaucorps, breeches, two shirrs, two cravats, hat, stockings, and two pairs of shoes; the petit habillement in the second year, consisting of waistcoat, breeches, two shirts, two cravats, hat, stockings, and two pairs of shoes. The uniform consisted of a grey-white justaucorps with blue lining and cuffs, blue waistcoat, breeches, and stockings, black tricorne and shoes. The buttons, buckles, edging, and braid were gold or copper coloured. The officers' privately obtained uniforms sported gold braid and edging, gilded buttons, and white tricorne plume. The sergeants' rank was signified by lesser quality gilt braid and edging and brass buttons. For corporals, gold-coloured woollen braid replaced the gilt. The cadet wore on the right shoulder a blue and white silk aiguillette or lanyard with metal tips, while the soldier was left with buttons of brass foil on wood. Waist-belts were of buffalo hide. The uniforms themselves were cut from fine woollen cloth with linings of serge and linen. Both justaucorps and waistcoat had three dozen buttons each. In addition, drummers wore distinctive complementary uniforms, consisting of a blue justaucorps with red lining and cuffs, red waistcoat, breeches, and stockings, black tricorne and shoes, and brass buttons. The justaucorps, waist-belt, and drum strap sported the king's livery lace; the drums were blue sprinkled with gold fleurde-lis. The drum major was indicated by velvet facings and braid of the king's grand livery. Other accoutrements included grey-white capes and greatcoats for sentry wear and foul weather, smocks of strong, twilled cotton fabric for work, and clothing maintenance equipment consisting of needles, thread, two boxwood combs, and two pounds of mottled Marseilles soap.

21 The second group was the Chevalier de Karrer's Swiss mercenaries. This regiment wore a reed justaucorps with blue collar-facings and lining, blue waistcoat, breeches, and stockings, and black tricorne and shoes. The waistcoat had double buttons with white buttonholes, the buttons being of moulded pewter and the edging and braid of silver. The full outfit also included boot sleeves, camisole, shirt, cravat, shoes, breeches, gaiters, collars, and waist-belts. Officers wore red plumes; drummers were distinguished by the colonel's livery lace and by lapels, facings, and collars in the regimental colour.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 622 The gunners, the Canonniers-Bombardiers, formed the third and last group. Their uniform consisted of a blue justaucorps with scarlet lining, facings, and cuffs, red waistcoat, breeches, and stockings, black tricorne and shoes. Buttons were of silver-plated German metal, the edging and braid of silver, the waist-belt of buffalo hide. The sergeant's rank was indicated by a double row of silver braid on the justaucorps sleeves, and the drummer sported a justaucorps decorated with braid decoration and king's livery lace.

23 These then are the material elements of which the Louisbourg costumed animation programme consists. Currently the Louisbourg costume study is in the final stages of consolidation. Textile research has widened in scope and attention has recently turned to such smaller ethnic and social groups present at Louisbourg as the Basques, slaves, and the clergy. Together they will add the finishing touch to a more complete and accurate portrayal of eighteenth-century Louisbourg.