Research Notes / Notes de recherche

Mirrors of the Architectural Moment:

Some Comments on the Use of Historical Photographs as Primary Sources in Architectural History*

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 11 Buildings and landscape have been popular subjects for the photographer ever since L. Jacques M. Daguerre captured the photographic image on a silver-coated copper plate in 1839. Buildings were compliant subjects. They stood still throughout the long exposure times and were surrounded by abundant natural light. Compositions could be worked at over hours, months, or even seasons. The glass plate and large field-camera format of the early commercial photographers combine quality, accuracy, and detail and so constitute a palimpsest of information levels for any historian concerned with the visual record.1

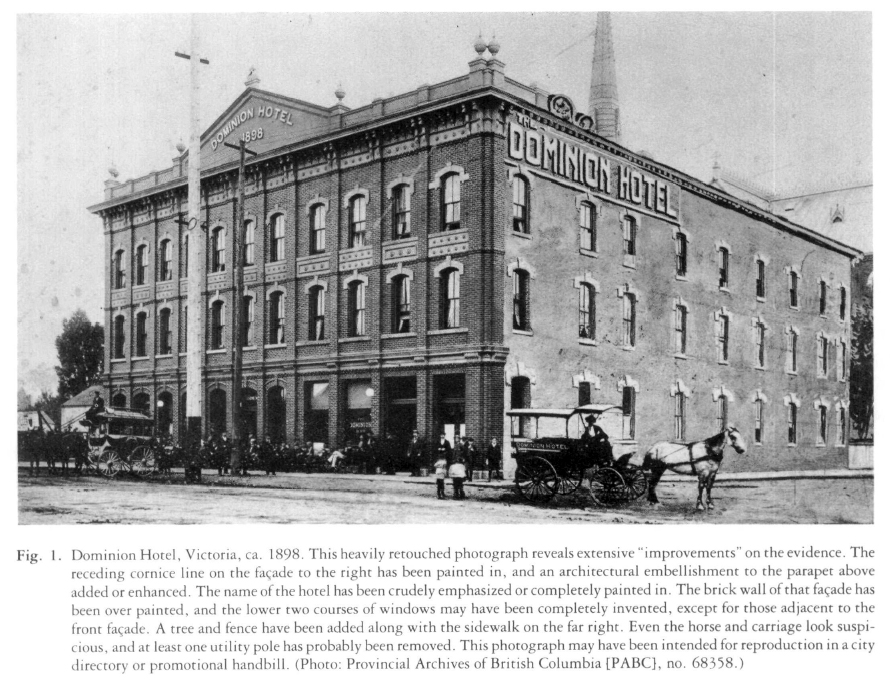

2 The common conjunction of the nineteenth-century camera and the commercial building façade was not accidental. Indeed the exuberance of late Victorian architecture may be in part a response to the relentless eye of the lens with its capacity for a limitless progeny of "as-found" images. The architectural façade was a public relations device; the commercial camera was a promotional tool. Indeed the very commercialism of early photography must put us on guard as to the veracity of the images produced. The products, now records, of the architectural photograph attest to this: souvenir picture albums, postcards, photolithographs for travelogues, promotional handbills.

3 The purposefulness, expense, and professional nature of early photography dictated a commercial economic context and, therefore, a "good show." To achieve this good show and a happy client (be it house owner or proud citizenry of a western boom town), photographers resorted to deliberate fakery.2 This often went beyond dropping in a dramatic cloudscape. Façades would be enhanced with improved and more elaborate detailing; merchandise displays might be added to shop windows; objectionable features could be erased. Very common was the alteration of signs on buildings to update the photograph or the featuring in a panorama of those structures sponsoring the prints. Accidentally or for aesthetic reasons a print could be reversed. Signs, automobile steering-wheel location, or such things as the button-side of clothes provide clues for correction. Often image alteration was not nefariously intentional. Commercial studios with large negative holdings could change hands, and the new proprietor would then change both the name and date on the plate.

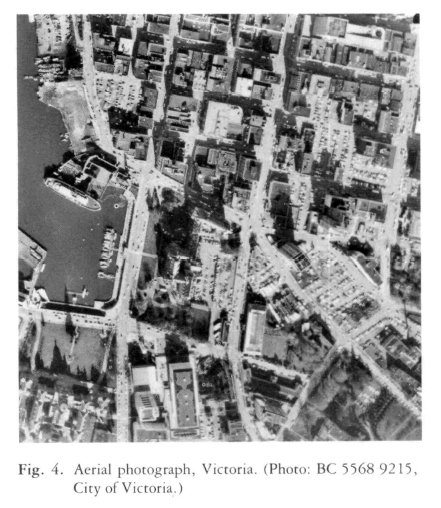

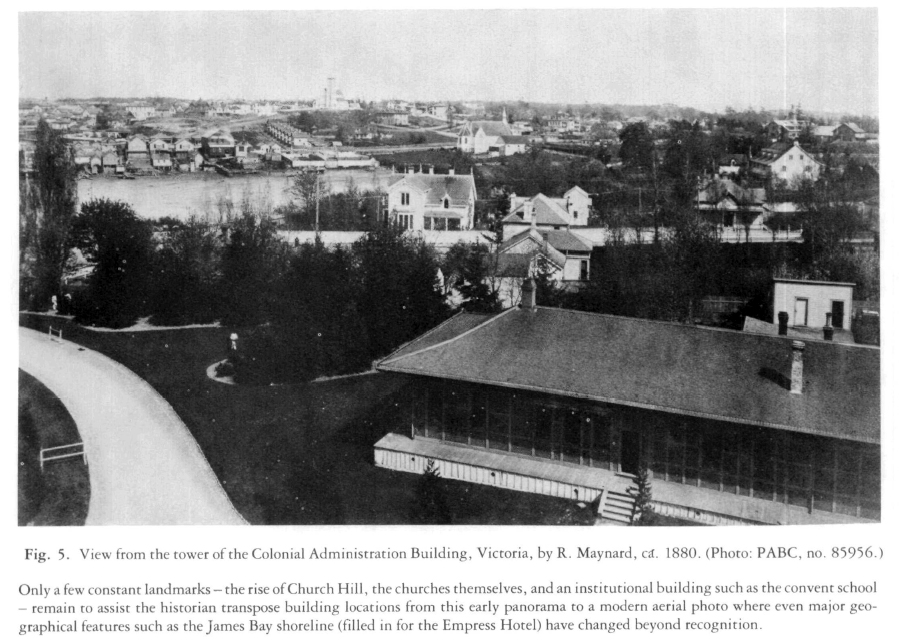

4 Professional architectural photography has traditionally been a special genre. It requires custom equipment such as the shift bellows and wide-angle lens. It often had specialist practitioners. Interior shots were particularly difficult and required skilled darkroom work to achieve a good image. Occasionally, such as in the work of Victoria's early twentieth-century photographer, Harry Upperton Knight, buildings were part of the aesthetic stage set for atmospheric photographic essays. More often the images were consciously documentary. In 1901, for example, photographers from the Montreal Notman Studio were contracted to record both events and scenery during the progress of the royal tour across the country. The Canadian Pacific Railway provided free passes to photographers and artists so that en route sights would find their way into the popular press by way of albums, postcards, and photographic exhibitions. Journals such as the Dominion Illustrated, published by a journalist-photographer, focused on the growth and development of western towns. Individuals commissioned photographs of their homes and businesses as mementos and to send to friends and relatives. The photographic team of Richard and Hannah Maynard recorded many of Victoria's prestige homes between the late 1860s and 1912.3 The notion of country- or empire-building was generally quite a conscious one, and photographers seem to have been aware of their historic role in documenting such "progress." C.S. Bailey, a Vancouver photographer, specialized in recording the urban landscape through progress photographs, a series done during the last years of the nineteenth century to record streetscape changes as seen from a number of fixed locations. His prints were shown at the Paris Exhibition in 1889, the Toronto Industrial Exhibition in 1891, and the Chicago World's Fair in 1893- It was common for cities and towns to use such architectural photographs in travelling exhibitions to promote trade, investment, settlement, and tourism.

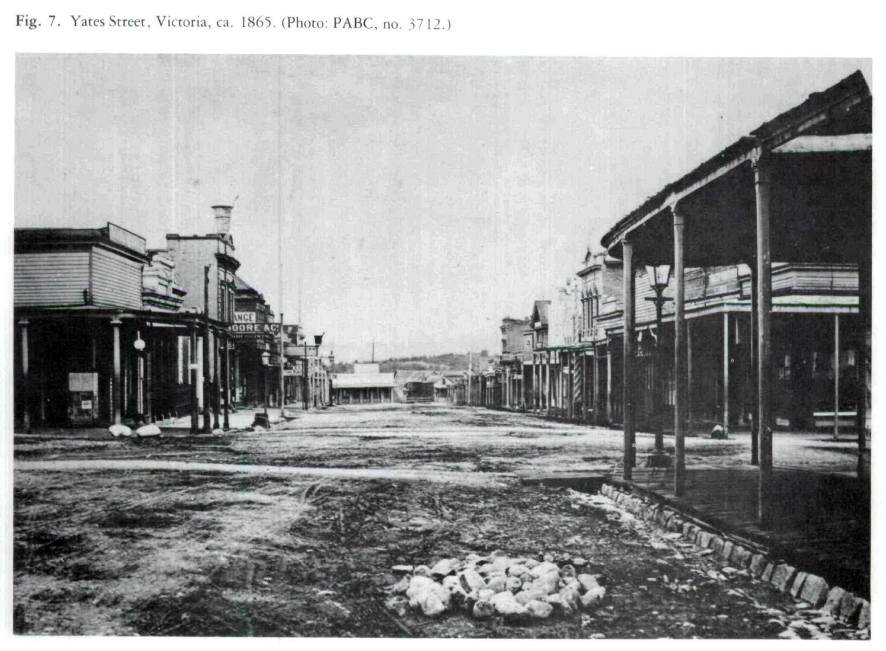

Display large image of Figure 2

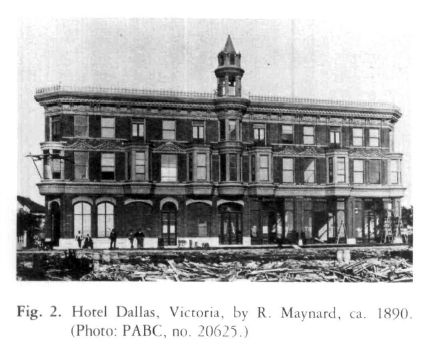

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

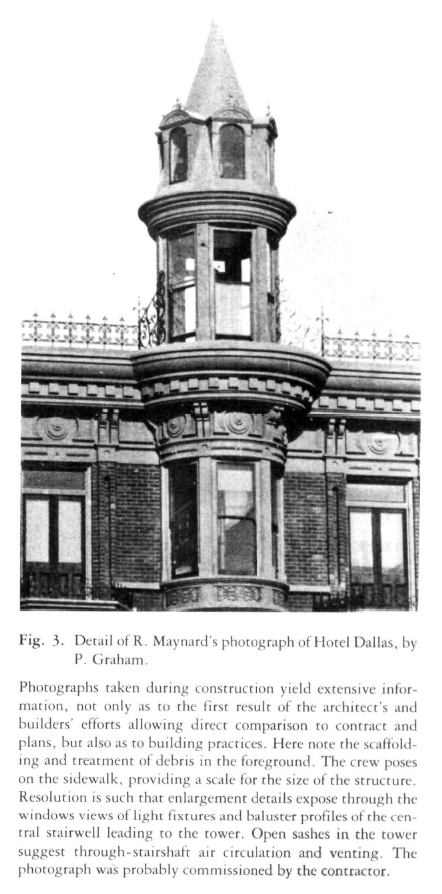

Display large image of Figure 35 Apart from the postcard view aimed at the tourist market, probably the largest market for architectural photography was the construction and real estate industry. Contractors required record photographs at various stages of the construction of major projects. An excellent series, detailing the unusual methods used to build the Crystal Gardens in the 1920s, survives in the Percy Leonard James album.4 Architect Samuel Maclure approaches professional calibre in his photographs -interiors, exteriors, and construction scenes-of the many important commissions that went through his practice in Victoria and Vancouver between 1893 and 1929. Many of these were published in architectural and trade journals in Canada, United States, Britain, and elsewhere.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 8

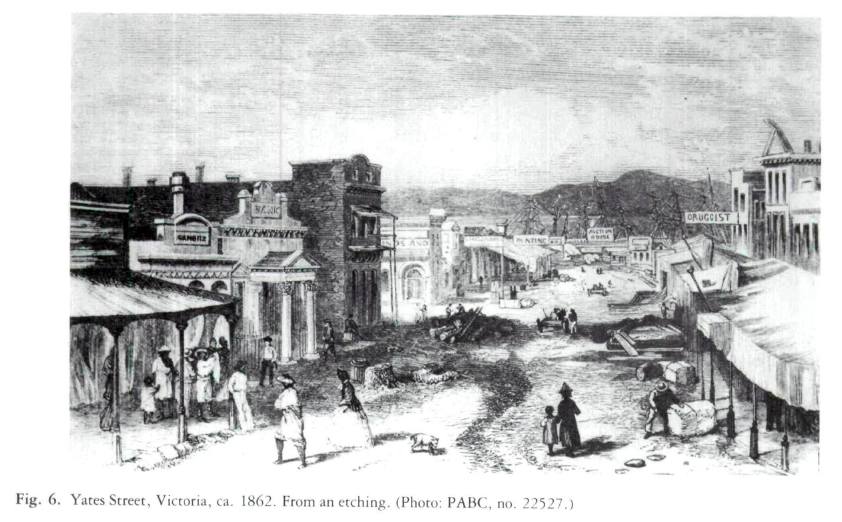

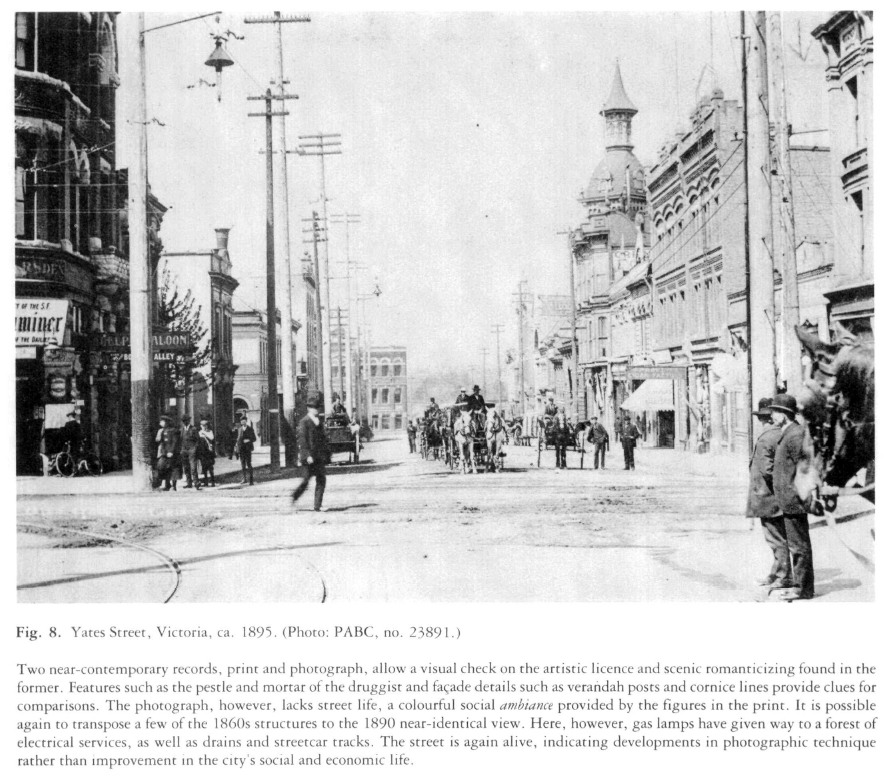

Display large image of Figure 86 Crucial to the dating and interpretation of the results of architectural photography is an understanding of its conventions. It is important to know whether the print was the private snapshot of an amateur or the commercial product of a professional. If it was formally posed, it probably featured proprietor rather than customer. The game aspect, including dressing up and visual jokes, was an important part of the photographic convention. Slow emulsion speeds encouraged the photographer to feature his built subjects in deserted streets. A crowded street might be the primary posed subject of the picture, the building an ancillary backdrop to an occasion. It was important for buildings to stand up straight; thus bellows and lenses were manipulated to achieve this effect with resultant distortion of proportions. Broadly speaking, four types of architectural photographs can be identified, each having distinctive traits, functions, and clients: the urban panorama, the streetscape, the single-building exterior, and the room interior.

7 The urban panorama, popular well into the twentieth century, contains a vast number of clues as to date (even season of year and time of day), and establishes a physical context for a structure. These photographs were usually taken from a convenient location with a good prospect of the town, such as a church tower, firehall hose tower, or hilltop. From the street life and the type and function of surrounding buildings, changing no doubt over a number of years, the skeleton of a social and economic history of a general store or residence can be constructed. The results of major historical interventions, such as fires, can be documented, as can those of minor ones like changing street patterns or the introduction of services - sidewalks, telegraph, telephone, gas, and electricity. Landmark structures or topographical features provide critical orientation clues for someone attempting to interpret the compressed perspective and distorted field of the wide-angle lens. These must, however, be read in conjunction with contemporary street maps, fire-insurance maps, which record changes as well as building materials, and the late Victorian favorite boom-town promotional device, the bird's-eye view with its numbered key of major buildings and businesses.

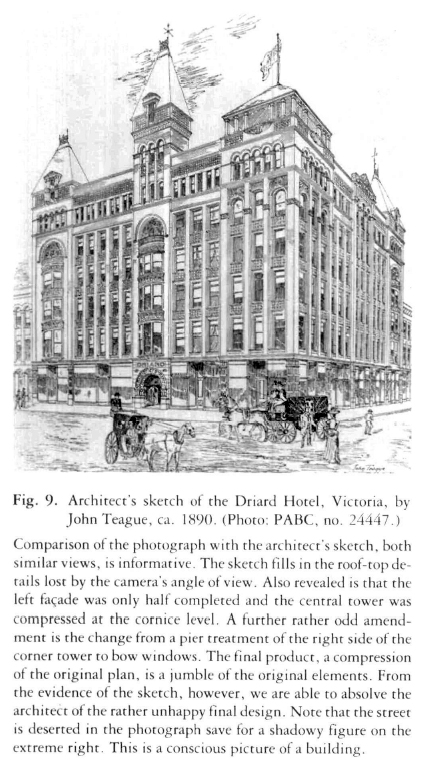

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 98 The streetscape was a common postcard subject. It summarized the visual impression of a town, particularly the business section. The false-front commercial structure with its concentration of detail in the single plane of the street elevation was most photogenic in this type of picture. The information here is contextual: the relationship of buildings to one another and the response of the street to a multitude of influences, from changing modes of transport to city ordinances. Among the latter, an important and major change to streets of the American northwest in the 1880s was the removal of front verandahs and balconies in response to city ordinances attempting to control the spread of fire. The type, style, and sophistication of store signs constitute a more ephemeral popular art-form which can help date the photograph. Here also is the literal evidence of the changing fortunes and functions of the buildings and the area. Suburban streetscapes on the other hand provide quite a different range of information. Fences and gardens are the ephemeral architecture here and record changes in fashion and personal taste.

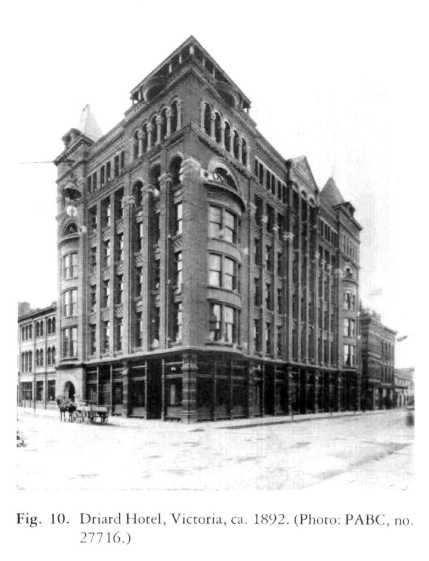

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 109 The single-building exterior photograph has its own closely followed conventions. Dramatic (high-noon(shading to emphasize decorative relief and the inclusion of the owner or tenant in front invite detailed examination, Under such close scrutiny, information as to measurement and scale becomes accessible. Types of materials and their quality can be identified while structural defects in the building itself provide clues as to loading patterns, mechanical and structural systems, and interior spatial organization. Wear marks document a history of Lists and abuses. Observable structural or decorative alterations reveal changes in use or even the shifting fortunes of the owner. The use of camera techniques to improve the tip-right appearance of the building caused some distortion. The general practice of ensuring at least one façade parallel with the camera plane does allow, however, the use of modern photogrametric methods of analysis whereby accurate measurements of the original structure can be obtained. The pictorial evidence can be compared with other primary sources including architectural drawings and contemporary descriptions in journals, letters, diaries, and account books.

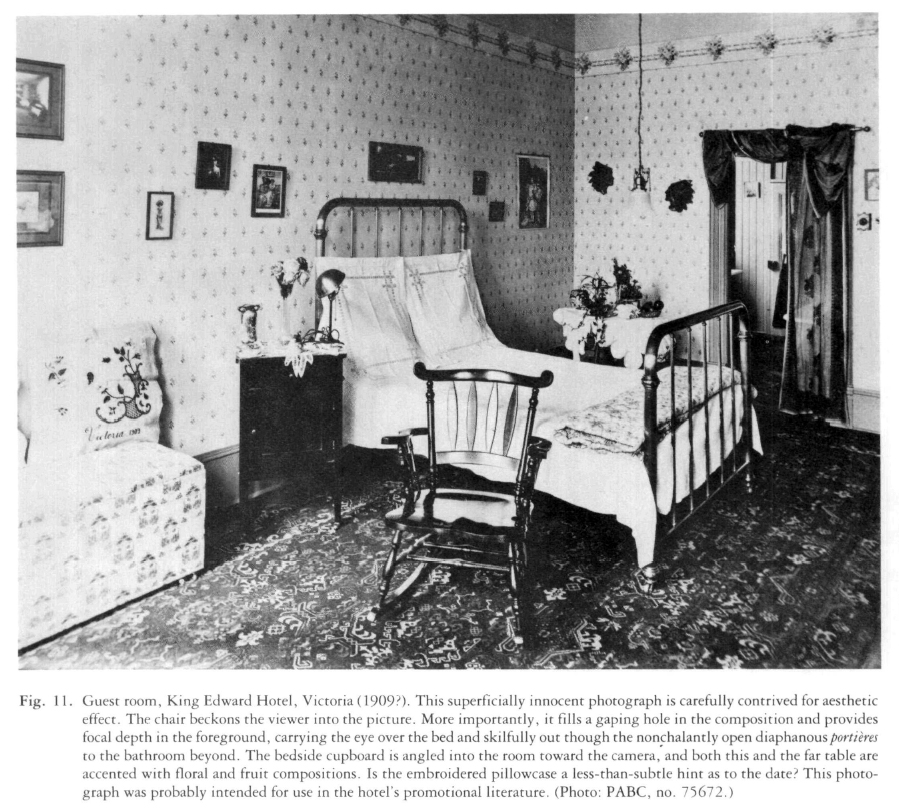

10 Interior views, although comparatively rare until the improvement of the magnesium flash and fast-speed film after 1900, yield further information as to structure and human activity. Interiors provide extensive data from which the way of life of the inhabitant can be extrapolated. Unfortunately he or she was usually as aware of this as we are, and the evidence was adjusted accordingly. Shifts in taste and fashion in the decorative arts and technology assist in dating; they also provide information for recreating the social history of the structure. Objects such as cut flowers suggest the time of year the photograph was taken. As these photographs were often consciously posed to include memorabilia and the furnishings important to the occupant, the images become as personal as a signature. Wallpaper, china, and pieces of furniture, therefore, denote life stories, as well as providing evidence of current patterns of communications and trade. For instance, one standard identifier for placing a Victorian house interior in the Pacific northwest is the presence of West Coast Indian baskets as sewing baskets, wastepaper bins, or merely containers for flower pots.

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 1111 When the Eastman-Kodak roll film camera became available in 1888, the age of popular photography was born, and from then the photographic record multiplies over the years. Until recent times, however, buildings have by and large been an incidental subject of amateur photography. In terms of quality and utility the professional architectural photographer has maintained his special preserve. It is important to remember that under his skilful direction the photographic image could be carefully controlled. Its frame could be selectively contrived, and its content manipulated to suit the market, client, or function. Like any other primary historical source, therefore, it is a document to be weighed along with other evidence.

* I am indebted to archivist David Mattison and architectural photographer Philip Graham for assistance in the preparation of this research note.