Reviews / Comptes rendus

Point Ellice House, Victoria, B.C.

1 By means of traditional, late Victorian room groupings within a restored home, Point Ellice House succeeds in portraying the material wealth, in quantity and value, associated with the home life of a well-to-do civil servant and his family. Restoration purists viewing the house in 1981 may be disturbed by the noisy, smoky, and pungent industrial plants which surround the grounds of Point Ellice. A few will take solace in the fact that the house narrowly avoided being razed during the 1960s in order to provide a parking lot for the sprawling sawmill next door and thus survives as the only residence on Victoria's once tranquil and fashionable Pleasant Street.

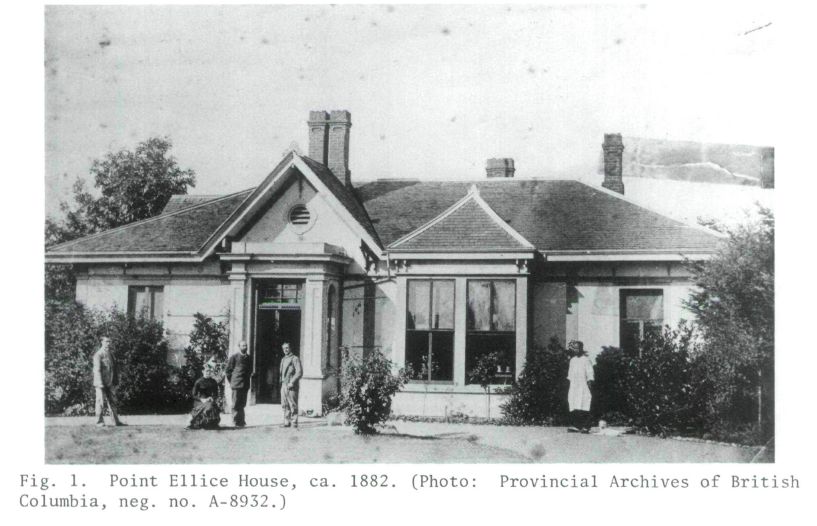

2 Peter O'Reilly arrived in Victoria from Ireland in 1859 and shortly afterwards was selected by Governor James Douglas to help keep peace and order in the gold fields of the newly created Colony of British Columbia. Between 1859 and 1898 he served in a variety of government positions: Stipendiary Magistrate, High Sheriff, Gold Commissioner, County Court Judge, an appointed member of the Legislative Council, and an Indian Reserve Commissioner. As the capital of British Columbia was being changed from New Westminster to Victoria, Judge O'Reilly decided to move his residence from Yale to Victoria and in December 1867 purchased a small house and garden from Charles W. Wallace for $2,500. This building, the nucleus of today's Point Ellice House, had been constructed in 1861. As O'Reilly became wealthier he periodically had alterations and additions made to the house until it reached its present plan in 1889.

3 One of the most outstanding features of Point Ellice House is the collection of O'Reilly possessions gathered by the family since the 1860s. Either used or stored there until the 1960s, most of the collection was amassed prior to the First World War, by which time Peter O'Reilly's death followed by waning family fortunes saw a marked decline in purchases for the household. Authentication for much of the collection has been assisted by extensive family papers, diaries, and correspondence, most of which are in the custody of the Provincial Archives of British Columbia. The documents contain some specific information on dates of purchase of items ranging in variety from pianos to sets of Minton china. As with many other families of their period, the O'Reillys seldom discarded used but serviceable possessions. Consequently, the storage areas in the attic and elsewhere included many artifacts that were retained, even though they had been replaced by newer ones.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Grandson John O'Reilly and his wife, Inez, former private owners of the house whose diligent restoration work was based on personal research and, as far as possible, on museological principles, opened it as a private museum in 1968. Interpretation focussed on the genealogy and historical significance of the family. Visitors were usually welcomed by a guide in period costume — often Inez O'Reilly herself — and were given a tour which emphasized the artifacts and events associated with family members. In 1974 Point Ellice House and most of its contents were sold to the Province of British Columbia and a curator, Michael Zarb, was hired to systematically catalogue the vast collection and to research the house and the O'Reilly family. After a term under the management of the Historic Sites Branch, Ministry of Recreation and Conservation, then later under the Parks Branch, Point Ellice House was turned over to the Heritage Conservation Branch, Ministry of the Provincial Secretary in April 1979. As no formally approved interpretive or development policies have yet been enunciated for the house, the curator has formulated his own which have received the tacit approval of the various administrations and which serve as useful guidelines in the day-to-day operations.

Display large image of Figure 2

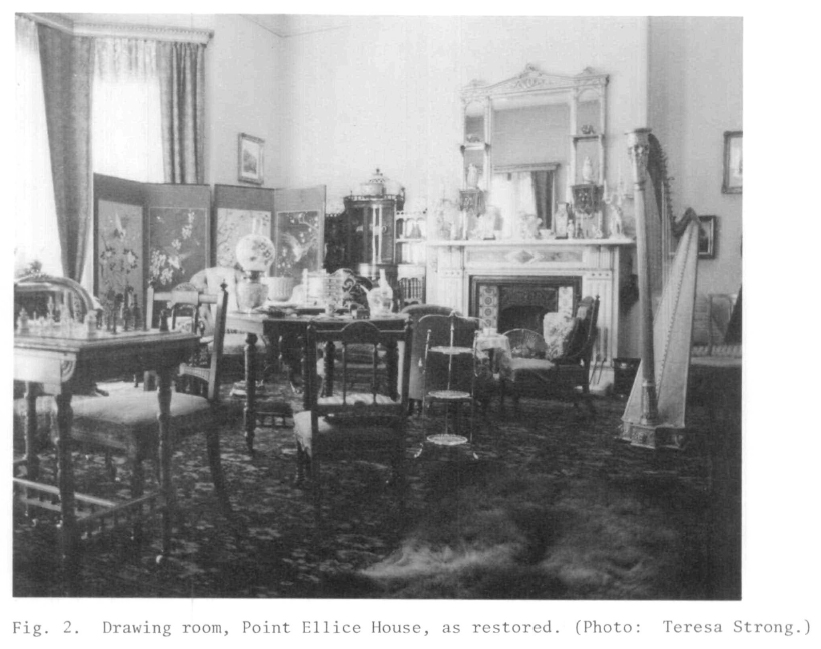

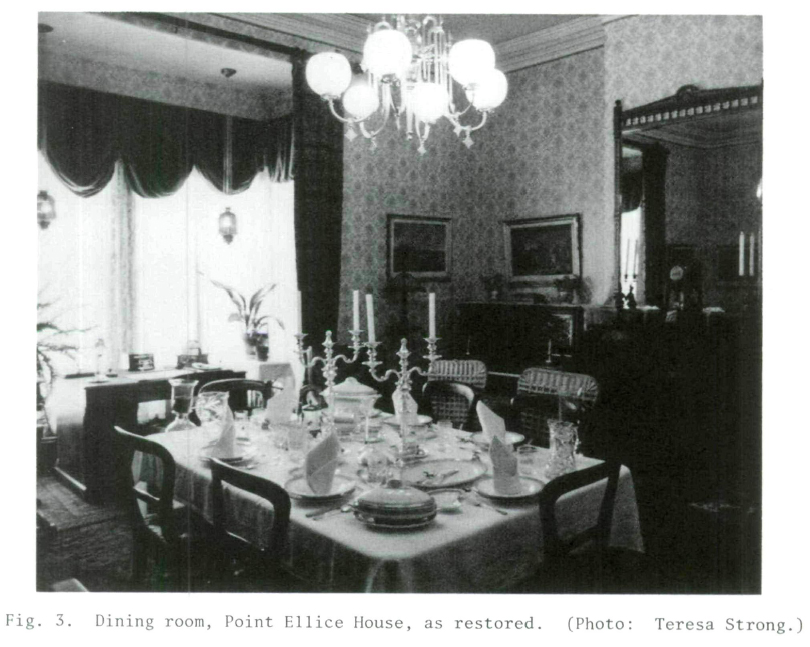

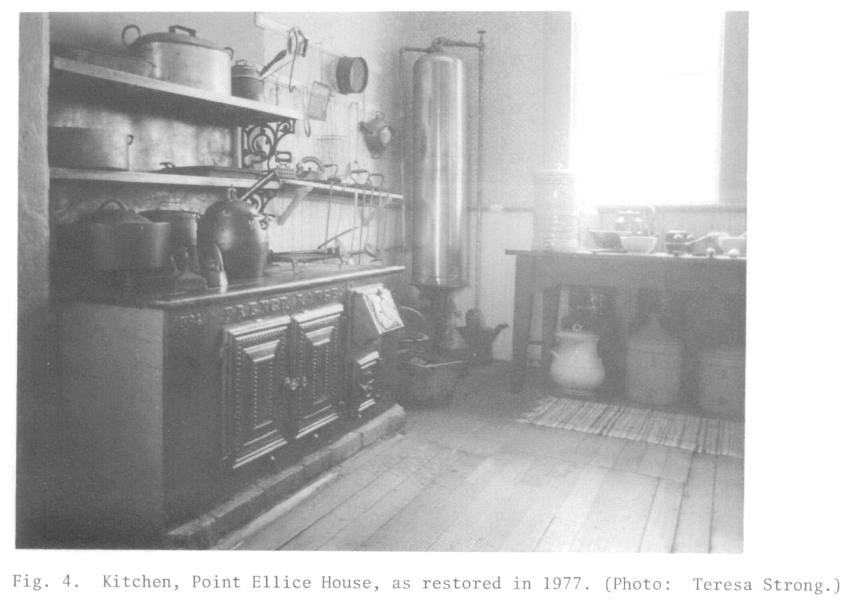

Display large image of Figure 25 The period of interpretation selected for Point Ellice House is 1890-1914. The curator has rationalized the starting point by verifying that the last addition to the house (the entire kitchen or northern wing) was completed in 1889. He does not think that demolition of the addition to allow for an earlier interpretive period is desirable or practical, based on the paucity of some exact details concerning the house's earlier configuration. The final date, 1914, was chosen as representing the last period before the O'Reilly family began to separate and the family finances began to wane.

6 Important in Zarb's interpretation of the house is its construction and growth, reflecting the O'Reillys' changing station in society and their family needs. Point Ellice House is noted by Martin Segger in Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1845-1929 (Watkins Glen, N.Y.: American Life Foundation and Study Institute, 1979):

The original dwelling of 1861 was subsequently added to in three stages, resulting in the house's low, rambling appearance. As completed in 1889 the house is one storey throughout with the exception of a small cellar and an attic over part of the house. The attic was used for storage and for temporary sleeping quarters for a maid, when one occasionally spent the night in the house. It remains one of the principal storage areas in the restored house. The house has two "fronts." The one facing the Gorge waterway was used as an entrance from the garden and for those arriving by water; the other facing east onto Pleasant Street was for those arriving on foot or by carriage. The landward entrance is today's principal one for visitors. Originally the doors on both fronts were centrally positioned on the western and eastern facades, but the later addition of a bay window north of the eastern door as well as the general enlargement of the house northward, conspired to create remarkably off-centre entrances.

7 The restoration of the exterior has been advanced to date without the full-time assistance of a restoration architect, although the late Peter Cotton was consulted and did offer advice from time to time during John and Inez O'Reilly's ownership. What they accomplished was, with a few exceptions, well-executed and accurate. One of these exceptions was the removal of the plain, rough-cast exterior stucco finish to facilitate the insulation of the walls. It was replaced by a stucco finish scored with lines to give it the appearance of a regular ashlar. Another exception is that samples of paint found in different locations around the house indicate that while white may have been applied to the house at one stage, it was not necessarily the stark white applied in the 1960s. Similarly, early photographs suggest that the trim may have been a darker colour than the walls, whereas, except for a thin black edging around window sashes, all trim in 1979 is painted the same white as the exterior walls. Again, while most of the wooden brackets and other decorative exterior mouldings have been restored, a notable exception is the absence of a cut-work finial which early photographs verify as having graced the apex of the central roof gable, above and behind the eastern front entrance. Lastly, the addition of storm windows is unauthentic to the period of interpretation in Victoria and, because they are quite noticeable to the viewer, warrant mentioning. Although they could have been made less obtrusive by reducing the dimensions of their frames and by not painting them black, they do serve the worthwhile function of assisting in the regulation of interior climate control.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 38 Inside, the curator has recreated authentic room groupings which reflect not just the general tastes of late Victorians but, more importantly, the personal tastes of members of the O'Reilly family during the 1890-1914 period. Furniture, fixtures, ornaments, and pictures are all virtually intact from the O'Reilly legacy. The selection of artifacts has been determined largely by contemporary written accounts, but the curator has also been able to deduce original usage in some cases. For example, a swing mirror missing from the top of a chest of drawers in a bedroom was identified from several others in the collection because it matched the size of scratches on top of the chest. Similarly, the exact placement of a dressing table in the same room was made possible by the unmistakeable wear marks in the carpet beneath the window.

9 Draperies, blinds, and some other accessories have been replaced by substitutes or reproductions which generally do conform to Victorian style and complement the other artifacts. In a limited number of cases, replacement period pieces have been introduced to fill gaps in the collection. Notable in this category are the chandeliers in the dining room and the hallway leading to the drawing room. These were collected by John and Inez O'Reilly to replace fixtures which had been lost or stolen. In both cases the replacements were obtained from houses in Victoria of similar vintage and quality and they do fit well into their new surroundings.

10 Original wallpaper adorns the master bedroom and the hallway leading to the drawing room. The one in the hallway, representing blocks of marble, is notable for having been laid horizontally. All other areas have been repapered with modern period reproductions. Generally, however, the choice of reproduction patterns is not suited to the late Victorian and Edwardian period of interpretation. Furthermore, it is likely that the wallpaper in the hallway leading to the kitchen wing is an anachronism; certainly the wallpaper in the kitchen is inaccurate and the curator aspires to applying calcimine to the walls when this is possible. All such redecorating was done prior to the government purchase and no upgrading has been undertaken since, although a great deal of scope exists for the accurate detailing of papers in most rooms because none had been stripped prior to the application of the last layers. Where original interior decoration exists it is a vital link in the overall interpretation; where post-1914 finishes have been applied, much is yet to be learned by careful stripping and scraping. The potential for a greater interpretive emphasis on the interior decoration certainly exists.

11 Several notable alterations to the house, carried out prior to its purchase by the provincial government, had been made in order to make it more comfortable for the inhabitants. The alterations, while not affecting major rooms, do detract from a full interpretation. For example, the change room adjacent to the master bedroom was converted into a galley kitchen and later to the curator's office. Victorian customs surrounding the bedchamber might be illustrated by the eventual restoration of the change room. Another restoration project would enhance the former box room, now a modern lavatory. The box room would be an essential feature for interpreting the nature of Peter O'Reilly's itinerant duties for it was in this room, originally opening onto his study, that he kept the many travelling cases necessary during his frequent perambulations around British Columbia.

12 The collection received some conservation attention during the period of private ownership and Zarb has continued a low-key but effective programme of conservation. Ultra-violet filters have been placed on the windows, the house's foundations have been strengthened, vents have been opened for the circulation of air beneath the house, and a vapour barrier installed to lessen further development of dry rot. (Improper workmanship during the 1960s had resulted in a higher incidence of rot in less than ten years than had occurred in the previous one hundred.) Zarb has been careful to ensure that original features have been retained whenever possible. For example, the original kitchen flooring was numbered for reassembly when crews removed it to work in the crawl space beneath.

13 To date formal visual interpretation at Point Ellice House consists of six interpretive panels using photographs and text to describe the history of Peter O'Reilly and the O'Reilly family generally, the history of the house, and of the Gorge area, though there is little to link this information with the collection. These panels are mounted in the frames of a portable Gothic-style screen. An interpretive unit of this type and size is unobtrusive in the midst of a restored home, yet offers an effective means of presenting data.

14 The curator is usually available year round for consultation and summer visitors are greeted by guides who conduct worthwhile tours of the house. Although school tours are provided on request, the limited time of the curator, the sole employee during winter months, precludes theme and activity programmes for students of a type which have proven successful in some other restored houses. A volunteer docent programme to assist with school programmes might eventually prove useful, but would be possible only when more staff are hired to free the curator for other duties. As with most restored homes, Point Ellice was not designed to accommodate large groups of people at one time, especially in passageways, a major factor in influencing school programmes as well as the movement of visitors generally through the house. In recent years partial entry into two rooms, a bedroom and the dining room, has improved visitor viewing, but may have done little to improve security or reduction of dust in those rooms. Also, while access to the kitchen has not been increased, a less annoying and more attractive barrier has been installed which still affords some protection for the collection.

Display large image of Figure 4

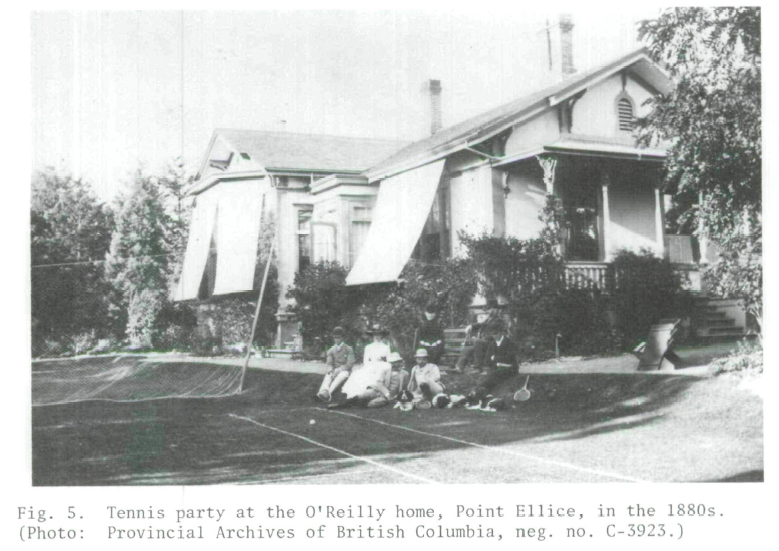

Display large image of Figure 415 The grounds of Point Ellice House, which were once the scene of lawn tennis, croquet, and extensive gardening and which also provided access to a boathouse on the Gorge waterway, are not currently restored beyond the stabilization of the lawns, gravel driveway, white stick fence, and gates in front of the property. Zarb's archaeological investigations have provided data about a former greenhouse and heating system and a kitchen midden. A wealth of written documentary evidence and photographs survive which would provide a sound basis for the restoration of flower and vegetable gardens and more fences, as well as the tennis court and croquet pitch. Late nineteenth-century seed catalogues exist in which former O'Reilly family members had indicated which species they planned to cultivate. To use these as sources for garden restoration would add another authentic dimension to the house, augmenting its restoration potential.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 516 For over ten years Point Ellice House has been open to the public as a museum, first private, now public. With only a few exceptions, the house and its collection as they have survived and been restored reflect accurately the late Victorian way of life in Victoria of one particular family. The house's strongest point is that many of the original O'Reilly family possessions remain and can be accurately documented, frequently by means of contemporary family records. Authenticity of artifacts and accuracy of interpretation are features which are stressed at Point Ellice House. But the work begun by John and Inez O'Reilly and now continued by Michael Zarb and British Columbia's Heritage Conservation Branch still has a long way to go before a total restoration is achieved.