Reviews / Comptes rendus

British Columbia Provincial Museum, "William Maurice Carmichael, Silversmith"

1 After some five years of diligent research and the application of a healthy acquisitions programme, the provincial museum has brought to light a fascinating chapter in the history of British Columbia craft industries.

2 British Columbia, despite periods of substantial wealth and a comparatively large, taste-conscious middle class, has produced few home-grown craftsmen or manufacturers in the decorative arts. In part this has been a function of its brief history and growth during a period when world communications and trade were improved to a point where local manufacture was barely economical and perhaps snobbishly unappreciated. Fashion, after all, was dictated by worldwide movements magnified by the European- and American-dominated specialty magazine business. Thus the New Westminster-based Blomfield family of stained glass manufacturers, Victoria's Scottish-trained decorative sculptor, George Gibson, or furniture manufacturers such as Victoria's Weiler Brothers represent the best of a very small group. To this brief list the name of William Maurice Carmichael, silversmith, must now be added. Robin Patterson, curator of the exhibition for the museum's Modern History Division, presents a definitive overview of Carmichael's artistic career spanning the years 1920-54.

3 W.M. Carmichael was Victoria-born and -educated, the son of a professional engineer and artistic mother who had trained at the Slade School of Fine Art. After a brief practice in civil engineering and service in the First World War, he opened his first workshop behind his parents' home in Oak Bay.

4 The first products were jewellery and electroplated tableware made to Carmichael's own designs. In 1924 a Sheffield-trained silversmith, George Bennett, joined the firm and showrooms were opened in Victoria. Expansion continued during the 1920s with the establishment of a larger factory on Government Street in 1927, followed in 1929 by the construction of the impressive Tudor revival business premises on Fort Street (fig. 1). The firm prospered, even during the 1930s. From 1935 to 1940 a showroom on Vancouver's Howe Street was maintained by the firm and supplied from the Victoria workshops. At the outbreak of war this was closed, however, and the firm concentrated on copper and brass utensils used to equip the warships being constructed and refitted in the shipyards at Victoria and Esquimalt. Major commissions over the years included church plate for Victoria's Anglican parishes, ecclesiastical accoutrements for the diocese, a mace for the cruiser H.M.C.S. Ontario, and flatware for the Capilano Golf and Country Club. On Carmichael's death in 1954 the business was turned over to the directorship of his second wife.

5 The exhibition is designed with thought and sensitivity. The artifacts are supplemented with photographs of the family, their residences, and the workshop along with sketches and designs from the hand of Carmichael. The Capital Curios Gallery, a small intimate space with vertical wall cabinets, is a permanent gallery designed for this type of exhibit. In fact, a recent guest was the Birks Silver Collection, the ghost of which still unfairly casts an unfavourable shadow on the more vernacular Carmichael products. The shallow cabinets are, however, excellent for close-up viewing; lighting is low-key, and designer Stuart Stark has correctly chosen the traditional green felt lining which shows up the silver while providing an unobtrusive period decor.

6 Arrangement of the artifacts is dense but not cluttered. The pieces are grouped by function rather than date, covering such categories as trophies, church plate, and table-ware. Attempts made to bring Carmichael's métier to life — photographs of the shop, designs beside the finished piece, interpretive graphics, examples, and die punches explaining the use of his personal hallmarks — are generally successful. Unfortunately this technique is not carried through to the tools which constitute merely a static display, uninterpreted and for the most part unlabelled. Labelling throughout the exhibit is sympathetic in design, but consistently sparse in information. Few items are dated and provenance is rarely mentioned — a frustration to the enthusiast. One interesting device for enhancing visitor interest is a brief interrogative display. A row of small spoons is presented with the information that Carmichael was asked to complete the set by replicating four originals. Which are the originals and which are the copies? The answer is provided. (This reviewer guessed wrong.) A period room with a table setting and silver service, dramatically lighted, breathes life into the exhibition and sets the Carmichael productions within their historical and cultural context.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 27 The exhibition succeeds admirably in its primary objective, to present in an informative way the career and craft of W.M. Carmichael to a general audience. An informed viewer, or collector, would perhaps be frustrated at the scant interpretive content. The beautifully designed folder gives an adequate summary of Carmichael's life. The lack of an artifact check-list is unforgivable. Furthermore, we are left wondering where Carmichael fits into the history of the British Columbia (or Canadian) craft industry. How good was he? To what extent was his workshop production from his own hand, that of his assistants, or from standard catalogue-ordered components? (Most of the beading and edging, for instance, was of a standard mass-produced type.) These questions are not answered. In part this may be a weakness of the Modern History Division itself which has traditionally paid little attention to cultural history, in particular the areas of fashion and taste. It therefore falls to this reviewer to attempt a brief assessment.

8 W.M. Carmichael was for the most part self-taught in his craft. His intelligence, talent, and, perhaps above all, connections and circumstances propelled him into a position where he was able to fill an immediate demand. Herbert Carmichael, Maurice's father, came to British Columbia as an engineer, finishing his career as Provincial Assayer for the Department of Mines. The family was wealthy, artistic, and talented. Like his father, Maurice also enjoyed the pastimes of Victoria's plutocracy such as the Dunsmuirs and the Audains, along with colonial remittance men like the Phillips-Wolleys. His second wife was a daughter of Sir Richard McBride, the former Conservative premier of British Columbia. The Carmichaels were devoted to shooting, fishing, and gardening. Thus the firm had an entry through the most prestigious phalanxes of British Columbia society to a distinguished clientele. In this Carmichael shared both interests and friendships with such fellow practitioners as society architect Samuel Maclure and architectural sculptor George Gibson.

9 In these times of rapidly inflating prices for precious metals, a silver collection is always impressive. A closer, more critical examination, however, reveals that, with a few exceptions, the product of the Carmichael shops was pedestrian. Especially in the revival styles, which describe the bulk of the exhibition, the designs are awkward, often clumsy, and consistently reveal only a superficial familiarity with the classical vocabularies. The more impressive pieces achieve monumentality mainly through accretion of ornament rather than grandeur of design. An example is the punch bowl, salver, cups, and ladle made for the Sick family (fig. 3). Maurice himself apparently described it as "dripping with grapes." Lack of design sensibility is further illustrated by Carmichael's drawings which are weak, often barely competent. (In fact, the best drawing in the exhibit is the Spurgen and Semeyn design for the Fort Street shop-front.)

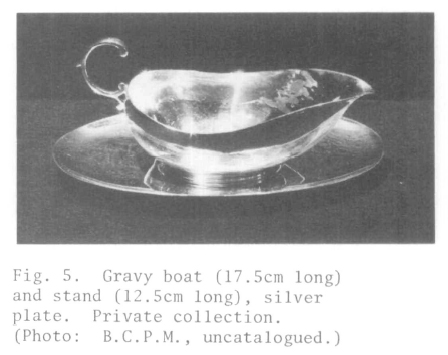

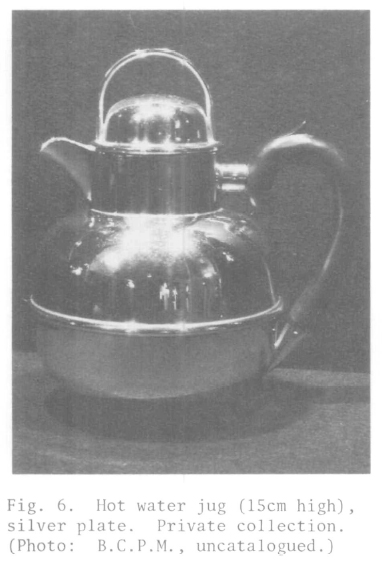

10 There are, however, some charming pieces showing design sensitivity and originality. These, interestingly enough, are the comparatively "styleless," non-revival pieces exhibiting a plain, almost arts-and-crafts or hauntingly modern effect. Some of the church plate, a gravy boat, a number of pitchers, and one or two tea services fit into this category. It seems that here Carmichael was most competent both as a designer and craftsman. The silver pitcher (fig. 4) is an elegant design based on the traditional English flagon. The deceptively simple form of the gravy boat (fig. 6), looking almost unfinished, an effect briefly accented by the flourish in the handle, is typical of the best work of C.F.R. Ashby. The crisp geometric lines of the hot water pot (fig. 5) give it a Bauhaus echo. In fact Carmichael's work in this manner carries many hints of Ashby's craft-oriented commune, the London-based Century Guild.

11 This sensitivity to the design tenets of the English arts-and-crafts movement would not have been accidental in the work of Victoria's major silversmith. Both generations of Carmichaels were supporters of the Island Arts and Crafts Society, the major exhibition organization and arts pressure group during these years. One of its founders and avid promoters, the craft revival architect and artist Samuel Maclure, designed the Carmichaels' St. Denis Street family home in 1911 and later the smaller house for Maurice and his second wife in the 1920s. Maclure died in 1929, but the Fort Street showrooms designed in that year by Spurgen and Semeyn are Macluresque in the extreme and express that fascination with the Tudor revival in which the arts-and-crafts movement in general, and Victoria in particular, revelled. It is not therefore surprising that Carmichael seems most comfortable in the craft idiom and that these examples are the highlights of the exhibition. While the output of the Carmichael workshop was prodigious and its products of fastidious quality, the best work was profoundly influenced by a distinctly local ethos, a particular fashion, which also generated the equally unique architectural contributions of Sameul Maclure, F.M. Rattenbury, and the James Brothers for which Victoria is already renowned.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6Curator's Statement

12 The Modern History Division's Carmichael silverware collection was started in 1975 with the purchase of a Georgian-style, five-piece, silverplated tea service. From that date on the collection has been added to by purchase and donation with the ultimate aim of having an exhibition of the pieces when sufficient research on the subject was completed.1 In February 1977 the Carmichael family kindly donated to the division a number of sketch books, a typescript biography, and many black and white photographs of Carmichael's pieces. Here was the core of an exhibition. The year 1980 was chosen for the Carmichael silverware exhibit because the gallery was available and five years of research had located the major creations.

13 The overall theme of the exhibit was to show the many facets of Carmichael's silversmithing business. Thus it was divided into various sections: church silver, domestic silverware, presentation pieces, large and spectacular creations, different marks used throughout the years of the business, a variety of paper objects related to the business, and a variety of tools used in the trade. In a further section of the gallery a period room setting was created to show afternoon tea as it used to be. This added both glitter and grandeur to the overall effect of the exhibit which is one of elegance and splendour.

14 For the future there are plans to travel a smaller version of this exhibit both nationally and provincially, beginning in 1982.