Articles

Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Newfoundland Gravestones:

Self-Sufficiency, Economic Specialization, and the Creation of Artifacts

Les études sur la culture matérielle d'une région présument souvent de la grande autarcie des premières économies pré-industrielles. L'utilisation de biens importés a pourtant fréquemment précédé la naissance d'une industrie artisanale locale, comme dans le cas des pierres tombales a Terre-Neuve. Au cours de l'été 1974, on dénombrait a Terre-Neuve, dans deux régions d'étude choisies, 206 pierres tombales taillées avant 1860. Les pierres antérieures a 1830 provenaient, pour la plupart, de l'ouest de l'Angleterre et du sud-est de l'Irlande. Les oeuvres de sculpteurs des comtés de Devon, de Dorset et de Waterford ont ainsi été retrouvées. Après 1830, la taille de la pierre s'est implantée "a St-Jean et l'industrie locale a rapidement supplanté la production européenne. Le grand nombre de pierres tombales importées va une époque aussi ancienne atteste des contacts de Terre-Neuve avec l'extérieur et limite l'importance de l'isolement dans la formation de traits culturels que présente l'île aujourd'hui.

1 The study of material folk culture is often marked by an assumed isolation of the culture in question. A region is frequently believed to have been materially self-sufficient, and the influx of mass-produced trade goods is taken to be a recent phenomonon. Some of these assumptions regarding economic self-sufficiency and the reliance on handmade, locally produced objects relate to an attitude of cultural primitivism with regard to earlier historical periods.1 The belief that earlier generations were obviously more self-sufficient has encouraged the idea that the objects which they produced were somehow of a better quality and design than those of our consumer-oriented culture. However, many regions of North America in the past few centuries were exposed to a wide variety of imported manufactured goods, and some areas relied as much on products from outside the region as on handmade, locally fashioned items. Newfoundland is such an example.

2 Much has been written on the supposed isolation of Newfoundland and the fact that the earliest fishermen had to make do in a self-sufficient economy.2 However, a look at early business ledgers, newspaper ads, or artifacts will indicate that just the opposite is true — that Newfoundland from its earliest years has been heavily reliant on imported manufactured goods.3 In fact, where in other areas of North America some goods such as handwoven cloth were produced for family or local use, in Newfoundland this material was imported.4 Many crafts which developed in other regions failed to flourish in Newfoundland because the economy remained extremely specialized; most residents were involved in the fishery, and goods produced by craftsmen were imported. Probably one of the most marked examples of this importation of craft goods during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was gravestones.

3 On an island that is often referred to as "The Rock" because of the quality of much of its landscape, gravestones used in Newfoundland before 1830 were not locally carved from native stone, but imported from the West Country of England or southeast Ireland, the homeland of most of the settlers. Although some stone such as local slate might have been suitable for such artifacts,5 residents instead ordered gravestones through the local merchant in their community who then contacted a craftsman in the European homeland. When completed by English or Irish carvers, the stones would be shipped several thousand miles to Newfoundland.

4 An initial survey of Newfoundland gravestones conducted from May through August in 1974 focussed on two areas of the island: the Southern Shore region south of St. John's, encompassing the communities between Petty Harbour and Trepassey, and the southwestern section of Conception Bay, between Harbour Grace and Holyrood.6 Forty communities were visited in these two regions, and all gravestones dating before 1860 were recorded. These two areas were chosen because they were two of the earliest settled on the island and they also provided samples from the dominant English and Irish immigrant groups.

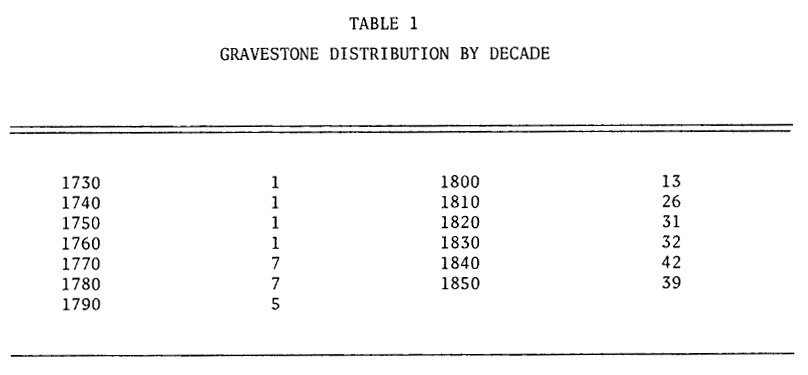

5 In the two regions surveyed, 206 grave markers were recorded dating before 1860 (table 1). Unlike some regions of North America, such as New England, where gravestone usage was common by 1700, seventeenth-century gravestones were not found in the study areas, and only twenty-three eighteenth-century markers were recorded. The earliest gravestone located was dated 173- (the last digit of the date had been broken off) and marked the grave of a Jenkins in Renews, most likely the magistrate in the region at the time. (There are older stones located in the Trinity-Bonavista area but apparently none date before 1720.7)

6 The absence of large numbers of gravestones before 1800 relates to several factors. Markers were expensive to buy, especially since they were shipped from England and Ireland, and only the wealthy merchant or government official could afford them. However, these same officials frequently retired back "home" to England or Ireland thus reducing even more the numbers of stones found on the island. In most communities surveyed gravestone usage increased dramatically with the presence of a local clergyman; since most communities did not have an established church until the early 1800s, this also kept the numbers of eighteenth-century stones to a minimum.

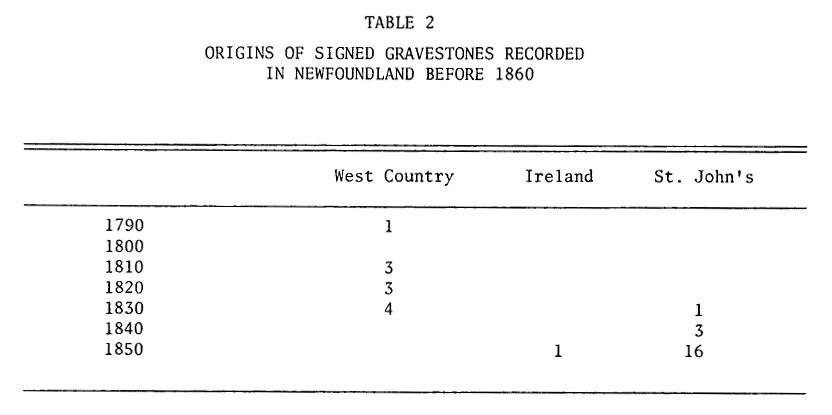

7 Carvers' signatures on some gravestones identify their origin, and although not all stones have a carver's mark, it is apparent that signed stones by decade give an indication of the general trends in origin (table 2). Between 1790 and 1830 seven stones contained West Country carvers* names. During the 1830s gravestone carving began in St. John's and by the 1850s almost all stones were locally made. This gradual shift in gravestone origins mirrors the entire shift in the Newfoundland economy from a mere extension of West Country-southeast Irish mercantile interests to an economy controlled to a greater extent by local merchants.

Display large image of Table 1

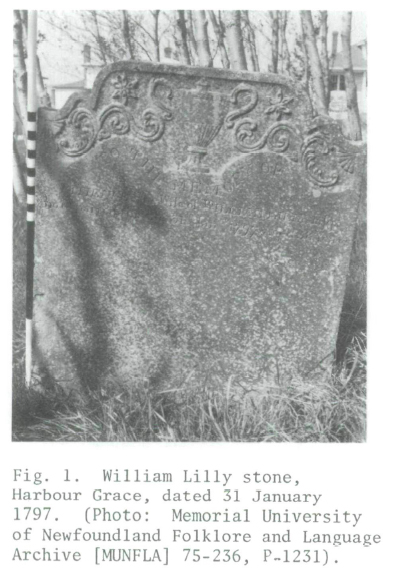

Display large image of Table 18 The earliest signed stone recorded was found in Harbour Grace, dated 31 January 1797 (fig. 1). This marker was also the only stone recorded that contained the name of a carver from the Bristol area of the West Country. The name "Bristol" is clearly visible at the top of the stone, but the carver's name which precedes it is partly illegible. However, a Bristol trade directory mentions a Golledge working in Bristol as a "marble mason" at roughly the same time, and this surname fits the portions of letters still visible on the Harbour Grace stone.8

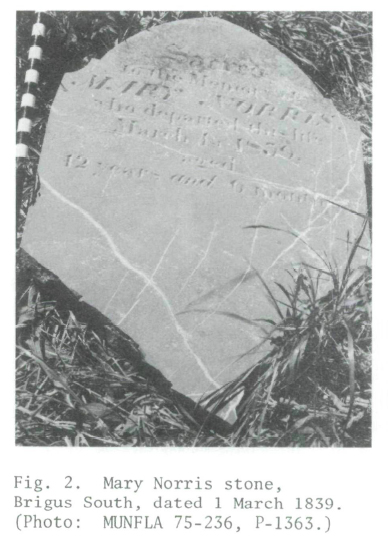

9 Since most of the surveyed regions were controlled by south Devon merchants at the time, it is not surprising that many of the early stones were carved by craftsmen in the port cities in this part of England. At the top of an 1839 headstone in Brigus South is carved, "H. CROSSMAN, Sculp." (fig. 2). Henry Crossman was a stone carver working in Newton Abbot, Devon, who had a shop on Wollborough Street in 1830.9

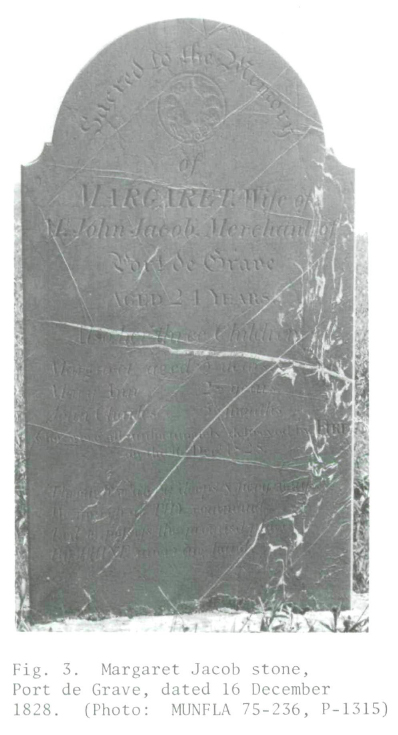

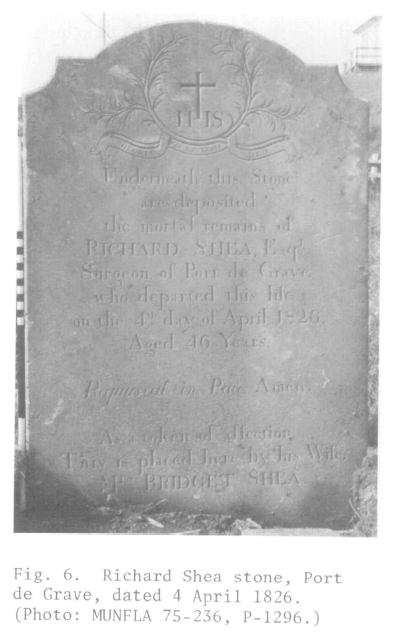

10 The Woodley family of St. Mary Church, Devon, carried on a flourishing stone-carving trade for many years. Two headstones in Paignton, approximately three miles from St. Mary Church, contain signatures of the Woodley family, one dated 1785 and the other 1795. Several of the Woodley works were shipped to Newfoundland. A headstone in Brigus, dated September 1814, clearly shows a Woodley signature, but the name of the town in Devon is illegible. Another stone in Port de Grave (fig. 3), dated 16 December 1828, is decorated by a small urn with the word "RESTO" in the middle, the same emblem used on the Brigus marker. A double stone, also in Port de Grave, clearly shows "Woodley" on the top left portion and "St. Mary Church" on the right. John Woodley headed the family business in Newton Abbot in 1830.10

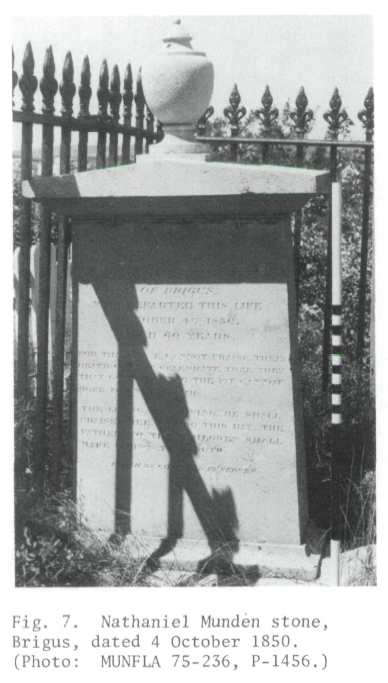

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

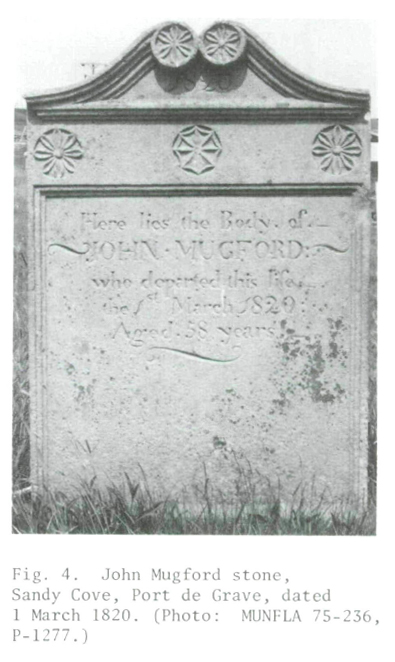

Display large image of Figure 211 Several other south Devon carvers provided gravestones for Newfoundland. A marker in Petty Harbour, dated 18 December 1812, was carved in Teignmouth by a mason named Knight, most likely John Knight who was working at Dawlish Road in Teignmouth in 1830.11 Jacob Grant carved an 1820 headstone found in Port de Grave (fig. 4). The Grant family worked as stone carvers in Dartmouth during the early nineteenth century.12 In Ferryland a headstone dated December 1827 was carved by a Devon mason by the name of Petherbridge. A Dartmouth craftsman, Pervman, carved a slate stone dated 21 November 1827, found in Bishop's Cove. In Port Kirwan a stone marking the grave of an Aylward was carved in Devon, although the name of the carver is now illegible.

12 Only one stone was recorded that contained the name of a Dorset carver. This headstone, found in Brigus and dated 22 March 1850, was signed by a Swaffield in Poole, most likely Joseph Swaffield whose business was located on Market Street, near the waterfront, in 1830.13 A trade directory of 1848 does not list any Swaffields, but this stone in Brigus indicated that the family was obviously still at work.14

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

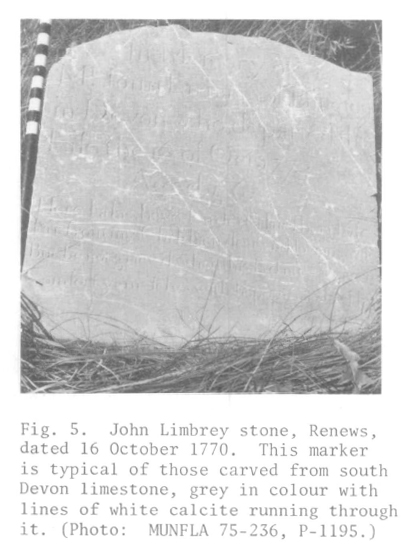

Display large image of Figure 413 While many pre-1830 English gravestones found in Newfoundland are not signed, they are often readily identifiable by the type of stone used. South Devon limestone, blue-grey with veins of white calcite, was widely used for the stones shipped to Newfoundland (see fig. 5).15 Quarries located along the coast near Plymouth, Torquay, St. Mary Church, Babbacombe, Brixham, Petit Tor, Totnes, Dartington, Berry Pomeroy, Ipplepen, Ogwell, Ashburton, Newton Abbot, and Chudleigh provided local carvers with an abundant supply.16 Lighter colour south Dorset limestone, quarried primarily at Portland, Purbeck, and Swanage, was also used though was not as common in the study regions.17

14 The Irish practice of signing stones was less common in southeast Ireland where most of the Newfoundland Irish markers originated. Identification took place primarily through comparison of styles. Many early Irish gravestones in communities such as Upper Island Cove and Brigus were identical in design and size. A marker at Port de Grave is typical with a central "IHS" motif flanked by scrolled carvings (fig. 6). During fieldwork in the city of Waterford, Ireland, in 1975, a pile of broken gravestones was located in a ruined chapel; these stones had been cleared from the nearby graveyard at St. John's Alley. Several of the stones dating from the early 1800s were identical to the Newfoundland Irish stones in style, material, and dimensions, and it is certain that a carver from the Waterford area supplied the stones located in Brigus, Port de Grave, and Upper Island Cove.18 The only recorded gravestone signed by an Irish craftsman, a Waterford mason named Kennedy, was found in Brigus and dated 3 July 1857.

15 The increasing scope of the Newfoundland trade in the early nineteenth century is indicated by several gravestones that were carved in other regions of the British Isles. A stone in Harbour Grace, dated 12 May 1833, was carved by J. Smith of Liverpool; a stone in Brigus, dated 4 October 1850, was carved by a Whitelaw in London (fig. 7); another stone in Brigus, dated 7 March 1857, was produced by a Wood in Greenock; a stone in St. John's, dated 17 August 1854, was carved in Glasgow by a Mossman.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 616 Beginning in the 1830s, gravestones began to appear that were products of St. John's craftsmen. The rise of the stone-carving trade in Newfoundland was largely due to the changing economic status of the colony. During the first three decades of the nineteenth century Newfoundland saw an increase in its economic and political independence, and many goods that were formerly supplied by West Country or Irish merchants were now manufactured on the island. Much of this political and economic independence was triggered by the American Revolutionary War and the Napoleonic Wars which isolated Newfoundland from England and forced her to begin to import skilled craftsmen to manufacture needed items. Keith Matthews, writing about the effects of the American Revolution, states that

Local merchants began to look to St. John's for supplies, and the Water Street shopkeepers gradually replaced the West Country and Irish businesses as suppliers of certain goods.

17 An unpublished census of St. John's, taken in 1794-95, reveals the numbers of skilled craftsmen who had settled in the city by the turn of the century. Three residents were listed as masons: Jas. Hayes, That. Todrige, and Thos. Walker.20 Although these men could have carved gravestones that were sold in the St. John's area, no signed examples of their work were located.

18 Besides an influx of skilled craftsmen, an increase in trade with Canada by the 1830s also contributed to the growth of a local stone-carving craft. Cut stone began to be sold at the docks in St. John's; for example, in May 1830 the following advertisement announced the arrival of such a shipment:

A quantity of Square

Freestone

Of good quality, suitable

for Building

Shipments of stone from Nova Scotia began to increase in the 1830s, and an 1846 advertisement by the Acadia Quarry in Pictou, Nova Scotia, announced the sale of various types of stones at the docks, including "Tomb Stones, 7 ft. long, 3 1/2 feet wide, 4 to 5 inches thick," at 2-7-6.22 These were blank stones that were then locally lettered by St. John's carvers.23

19 With the increased importation of stone to the island the carving trade in St. John's began to develop. The earliest gravestone signed by a Newfoundland carver was dated 2 July 1836. This stone, in the General Protestant Cemetery in St. John's, was carved by James Gray. A stone in Harbour Grace, dated 1842, was also carved by Gray and both markers, which contain only lettering, indicate his plain style. His work signals the shift of the carving of grave markers used in Newfoundland from the British Isles to the island, but his products are virtually identical to English and Irish varieties.

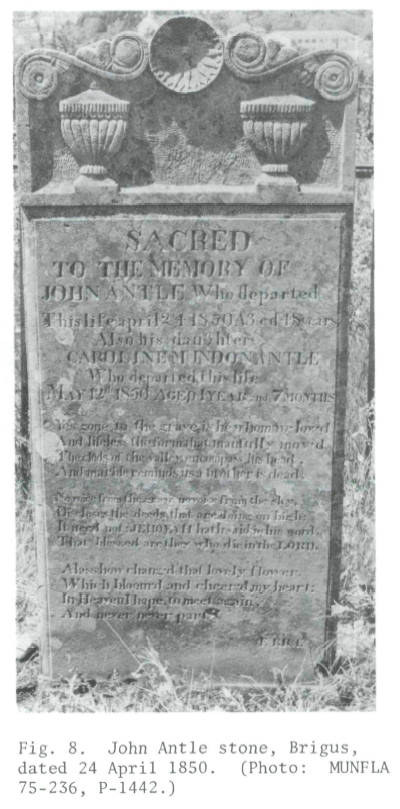

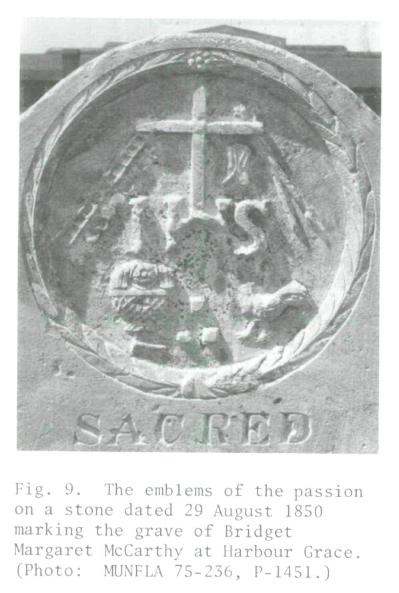

20 The work of Edward Rice, another St. John's carver, clearly indicates the changes which gravestones in Newfoundland experienced during the early nineteenth century. The earliest recorded example of Rice's signed work was found in Brigus and consists of a plain headstone with an incised cross as the only decorative work. This stone, dated 2 March 1850, is similar in style to the early, plain, Irish gravestones imported to the colony. Several months later, however, Rice carved another stone for use in Brigus which was elaborately carved (fig. 8). This gravestone contained two urns and a circular motif in the tympanum and was clearly a radical departure from the plain decorative tradition of the past. Rice's contact with the more elaborate Irish gravestone tradition is evident in a stone that he carved for use in Harbour Grace, dated 29 August 1850 (fig. 9). Like an Irish stone found in Port Kirwan, this marker contains the emblems of the passion, again a drastic change from most of the plainly carved stones imported from Ireland.24

21 The most prosperous of all nineteenth-century St. John's stone carvers was Alexander Smith whose work clearly indicates the extensive use of decorative carving as well as the increasing use of imported white marble. The earliest recorded work of Smith's, found at Bareneed and dated 23 May 1851, has an elaborately carved tympanum containing a cherub, with a shroud draped over the top of the stone. This marker is one of four located in Bareneed, all standing in a row, that were carved by Smith with virtually the same design.

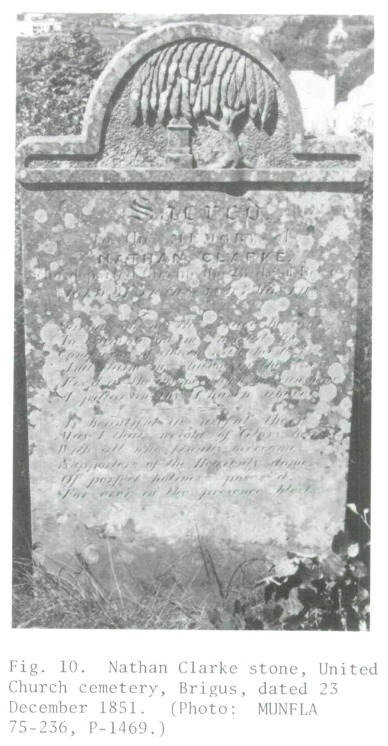

22 Smith's production of elaborately decorated artifacts is evident from two gravestones, dated 13 January 1846 and 23 December 1851 (fig. 10), found in the United Church cemetery in Brigus. These markers both contain an abstract willow tree in the tympanum, a motif that was unknown in Newfoundland until the 1850s. By 1853 Smith had begun to import white marble for gravestone use, probably the first carver to do so in Newfoundland. An 1853 marker at Cupids used this material, and a decade later virtually all gravestones in Newfoundland were made of this type of imported stone. Smith, whose "St. John's Marble Works" was located at 276 Gower Street, was in business until at least 1885,25 and his work was recorded in all regions that were surveyed in this study.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 823 A relatively large number of stone carvers worked in St. John's during the latter half of the nineteenth century. A large stone in Brigus, dated 23 December 1845, was carved by G. Bonfield. A Port Kirwan gravestone, dated 11 February 1853, was carved by a MacKim whose family carried on a stone-carving business until at least 1871. Another stone at Port Kirwan, dated 23 August 1855, was carved by a St. John's mason by the name of Cameron. J. Hay was carving gravestones in St. John's at least by 1856; markers at Bay Bulls, dated 3 April 1856, and Cupids, dated 30 June 1857, indicate the widespread distribution of his work.26 He was working until at least 187127 and it appears that a relative, perhaps his son, William Hay, took over the business by 1877. One gravestone in Port de Grave is signed by a Royce, dated 30 April 1848, although there is no place of business below the surname. This carver may have also been working in St. John's.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 1024 The earliest gravestones used in Newfoundland were products not of the local culture, but of craftsmen working several thousand miles away in a greatly different social and economic context. The actual presence of these gravestones in Newfoundland during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries speaks more about the local culture at the time than the specific symbols or epitaphs found on the stones. As a stonecarving craft began to develop on the island in the 1830s, the objects that were fashioned often followed the stylistic trends characterizing gravestones in many parts of the British Isles and North America at the time — a proliferation of cherubs, urns, willows, flowers, hands pointed skyward, crosses, crowns, and the like.29 The use of these styles in so many regions points to the dangers of assuming that the designs per se on locally produced objects are necessarily indicative of regional values.30 That Newfoundland gravestones, especially in the 1700s, did not utilize local designs does not make them any less important in the study of the past. What it does point out is the limitation in designating those objects that are locally made as holding the most information about a particular region or culture. This stress on the creation of an object by a local craftsman neglects aspects of the object's use as well as its distribution in terms of trade contacts. With regard to Newfoundland, if only locally produced objects were considered important for material culture research, then the sample of eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century items would be small. But if we consider the wide range of imported objects and how they were used, we can begin to understand the workings of an economy that was highly specialized long before other areas of North America. As well, the importation of objects such as gravestones indicates myriad contacts with the outside world and the fundamental weakness of explaining so much of Newfoundland cultural life through the myth of isolation. Hundreds of gravestones on the island from the British Isles and Ireland stand as monuments even today to the pervasiveness of artifactual — and therefore intellectual — contact with the outside world of the time.