Articles

Newfoundland Outport Furniture:

An Interpretation

Les meubles des villages côtiers de Terre-Neuve occupent une place importante dans le patrimoine de cette province. Comme les gens fabriquaient la plupart de leurs meubles au lieu d'avoir recours à un ébéniste, ceux-ci témoignent non seulement des talents et des particularismes des personnes qui les ont faits, mais aussi du mode de vie, des idéaux et des aspirations propres aux habitants du littoral terre-neuvien. Cet essai examine brièvement le mobilier des villages côtiers de Terre-Neuve et en étudie le style, la matière et les techniques dont on se servait pour le fabriquer, les finis, la décoration et les ferrures. Seize meubles typiques trouvés dans diverses localités font l'objet d'une description détaillée.

Introduction

1 At the time of permanent European colonization of Newfoundland by the English, Irish, and French in the early eighteenth century, the small population was sparsely scattered along the entire coastline. These early Newfoundland pioneers had to be self-sufficient in practically every aspect of their lives. They obtained a livelihood by fishing, chiefly for cod and salmon, and also by hunting and the pursuit of subsistence farming. One of the first chores of these early settlers was to construct fishing premises such as stages and flakes and temporary and later permanent houses for their families. The men built the houses from local timber and it was then the women's responsibility to do the interior decorating such as whitewashing the walls, hooking "mats" or rugs for the floors, and making quilts. However, the provision of household furniture was solely the responsibility of the men who constructed the basic items such as tables, benches, settles, chairs, and beds first.

2 The craft of furniture making was practised and traditionally transmitted in rural Newfoundland until at least the third decade of the twentieth century. By the late eighteenth century some furniture was imported and some made locally by coopers and other professional craftsmen. Most items were made by the local people for their own use because the small outport populations remained isolated from commercially-made products and generally out-port Newfoundland did not become a wage society until the 1940s.

3 This essay will briefly examine outport furniture, discuss style, materials used, construction techniques, finishes, decorations and hardware, and describe, in some detail, sixteen examples of furniture found in various settlements in Newfoundland. Because of the dearth of published information concerning outport furniture, this discussion is based upon insights acquired during twelve years as an antique collector and dealer and also upon information gathered recently with the help of a Canada Council Explorations grant. Since 1968 the author has examined several thousand pieces of outport furniture representing most of the older communities in Newfoundland.

Style

4 Early outport furniture was chiefly inspired by pieces remembered from the British Isles or was a modified imitation of current British styles. The earliest models found are simple in form, especially the chairs and settles which had solid backs and sides. Such furniture, which was easy to construct and likely to endure, continued to be made until the early twentieth century. The large pine settle (fig. 1) found in Harbour Main, Conception Bay, was probably constructed ca. 1850. This example is typical of the solid board type traditionally used in the kitchen in rural Newfoundland.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 15 The more elaborate or complicated furniture produced by British cabinet-makers was seldom copied. Windsor chairs, for example, were difficult to construct and were not locally made except in rare instances. On the other hand, the spindle-back chair of the Carver type, which was popular in the British Isles and some parts of North America during the seventeenth century, continued to be made in the Newfoundland outports until the late nineteenth century. This type of chair was durable and relatively easy to construct, requiring only a lathe for legs, rungs, and spindles.

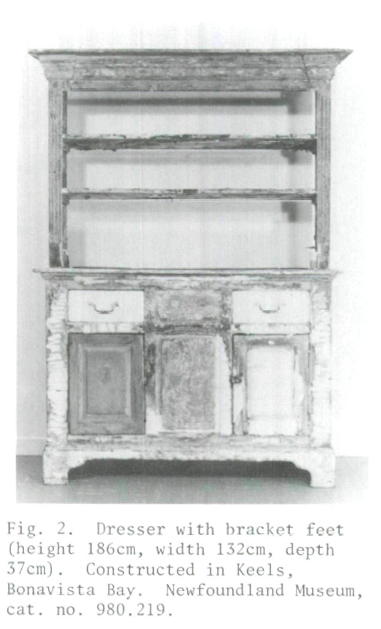

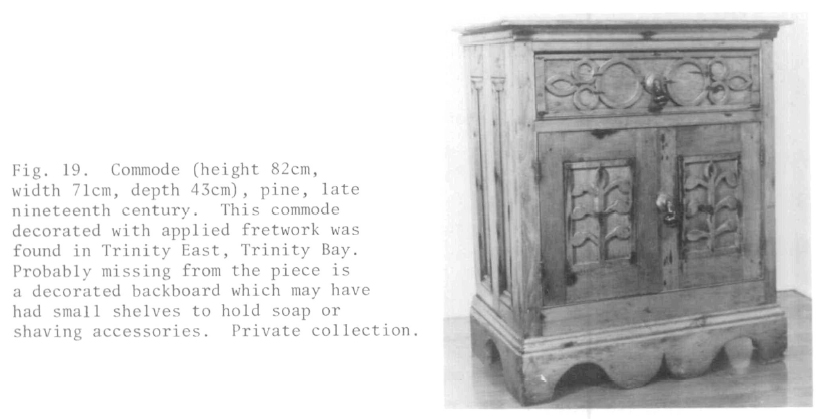

6 Rural furniture continued to be fashioned after eighteenth-century English styles until the early twentieth century. The bracket foot, a characteristic of both Queen Anne and Chippendale styles, was copied on case furniture such as cupboards, blanket boxes, chests of drawers, and commode-type washstands.

7 An early nineteenth-century pine dresser with bracket feet (fig. 2) was found discarded in a marshy area in Keels, Bonavista Bay. The centre drawer is actually a dummy; the Chippendale-style ball and bail handle originally attached to it is now missing. This well-designed dresser was built into the kitchen of a much older house than the one from which it was recently taken. It was first painted white and blue. At a later time part of the stiles were cut away, the facings of the shelf edges removed, and glazed doors added to bring the piece in line with current fashion.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 Several Chippendale-style chairs, made early in the nineteenth century, have been discovered on the shore of Conception Bay and the south shore of Trinity Bay. Only two are simple interpretations of the ladder back type, while the others have pierced backs. The late eighteenth-century Hepplewhite and Sheraton styles, which feature simple, straight lines and a minimum of carved decoration, were often imitated and interpreted with modification by local craftsmen. The most easily recognized and most frequently appearing characteristic is the square, tapering Hepplewhite leg found on tables and chairs. This leg style, which sometimes terminated in spade feet, was widely used and it survived in outport furniture because it was relatively easy to shape with ordinary hand tools. No chairs imitating the Hepplewhite shield, oval, heart, or wheel back have as yet been reported. On the other hand, many kitchen and dining chairs and even rocking chairs were made with the rectangular back of the Sheraton style but had the square, tapering Hepplewhite leg rather than the turned Sheraton leg. The early nineteenth-century Regency or Empire style, which was inspired by the heavy Empire style of Napoleonic France, also became popular and influenced the shape of rural Newfoundland furniture. This influence is found in the lyre-curved ends frequently seen on sofas and in the overhanging drawers found in the top tier of many sideboards, chests of drawers, and even late nineteenth-century commode-type washstands.

9 During the Victorian era when furniture in North America and Europe was being factory-produced, some Newfoundlanders using hand tools continued to imitate generally the earlier simple designs. A few industrious individuals, however, interpreted the commercial furniture with its ornate carvings, fret-work, and turnery. Homemade, foot-operated lathes and fretwork machines were sometimes used by these few innovative craftsmen to produce such embellishments. Mass-produced chairs, nevertheless, were seldom copied because they were difficult to imitate and were inexpensive to buy. Whatnots were constructed in the Newfoundland outports from pine and birch and usually resembled the factory examples that inspired them. The late nineteenth-century whatnot (fig. 3) made by A.L. Jensen's forbears in Belleorum is unusual. The shelves are supported by flat, shaped pieces of wood rather than by turned spindles and the front edges of the shelves are decorated with a pierced apron which resembles bargeboard seen on houses in Belleorum. Unusual features like the shape of the legs are reminiscent of Victorian cast iron furnishings.

10 By the beginning of the twentieth century the local traditional furniture still exhibited characteristics of both earlier and contemporary styles. Frequently a single item reflected a combination of several styles from different eras. For example, a twentieth-century chest of drawers might have bracket feet of the eighteenth-century tradition, an overhanging top tier of the early nineteenth-century Regency style, and a backboard in the shape of a lyre, an early twentieth-century feature of the furniture made during the reign of Edward Ⅶ.

11 Although outport furniture imitated the recognizable features of these styles, the size and proportions of each piece of furniture were usually determined by its location in the home. For instance, because bedrooms were often small, so too were chests of drawers and washstands. In fact, in a salt box type house, front bedrooms often measured no more than three metres by three metres and rear bedrooms were considerably smaller so that much bedroom furniture was frequently made exceptionally shallow, perhaps to fit behind a door. On the other hand, parlours were often relatively spacious and accommodated large sideboards which in turn were used to display ornamental glassware and dishes.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 Because outport Newfoundlanders were not normally schooled in formal furniture design, their uninhibited imaginations often interpreted styles in interesting and unexpected ways and sometimes the shape and decoration of the furniture was influenced by items a professional furniture maker would consider to be unorthodox.

Woods

13 The early rural furniture was made from locally available wood, chiefly pine and birch. Pine was the most popular, especially for chests of drawers and other case pieces, because it is a straight-grained softwood easily worked with simple hand tools such as saws, wooden planes, spoke shaves, chisels, and knives. Birch, a hardwood, was selected for its strength and because it can be turned on a lathe without splitting. It was used principally for the legs of tables, the legs, back, rungs, and spindles of chairs, and the posts of beds. Spruce, fir, and tamarack were only occasionally used since these woods are of coarse or uneven grain, split easily, and are difficult to work.

14 By the nineteenth century imported pine, birch, and maple were sometimes used for furniture making and boards from demolished houses and outbuildings were often used. In fact, parts of older furniture such as legs, rungs, spindles, and posts were occasionally incorporated into new pieces which were under construction. A rocking chair (fig. 4) made in Keels, Bonavista Bay, ca. 1950, is an example of how some materials were re-used. Most of this chair was fashioned by its maker, but the arms and rockers were taken from a factory-built chair which probably had become damaged beyond reasonable repair. Although one of the spindles comprising the back has been broken and replaced, the chair is nevertheless sturdy. Notice how the back was braced. The legs were similarly reinforced where they join the seat. Also notice the spindles, rungs, and legs that were carved by hand to simulate lathe work.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 415 Around the turn of the twentieth century, outport people saved packing crates specifically for making furniture. The boards from these crates, which consisted of pine, spruce, fir, or even tropical woods, had a disadvantage in that they varied greatly in quality, but there were advantages in that they were already cut, reasonably seasoned, and cost nothing. Furthermore, many of these boards were thin and particularly suitable for making drawer bottoms and panels. Furniture from this era has many examples of backs, panels, and inner parts made from these boards. Occasionally, an entire item was constructed from such packing-case material.

Construction

16 The stiles and rails that formed the basic framework of case furniture and doors were nearly always joined by mortice and tenon joints secured by wooden pins. In some well-made examples corner blocks were glued to the inside of the basic structure for strengthening. Panels were left free to expand and contract as the wood "breathed." The sides of case furniture and doors were often made from solid boards which sometimes had simulated panels made by applying mouldings or by carving away the centre of the board so that the edges stood out in relief.

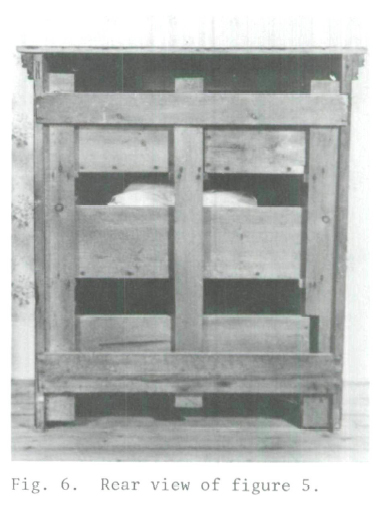

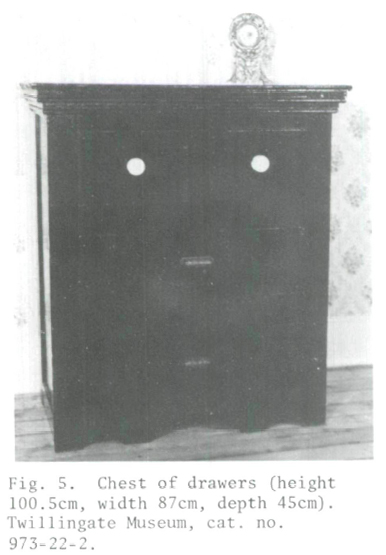

17 Chests of drawers, cupboards, and sideboards were frequently made without backs. The late nineteenth-century pine chest of drawers (figs. 5,6) from Twillingate, Notre Dame Bay, is an example of such furniture. The rear view of the chest also shows how the maker prevented the drawers from being pushed through the open back.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 518 The corners of drawers were most often joined by nails rather than by dovetail joints. The ends of the drawer front were cut to half thickness so that they overlapped the ends of the sides. In most cases the nails were driven through the sides of the drawer into the end grain of the drawer front.

19 Blanket boxes and travelling boxes were usually made from six wide pine boards. The corners were almost always joined by nails but occasionally dovetail joints were used. On the inside at one end of the box, a small document compartment with a hinged lid was built. Most boxes sat flat on the floor but some were supported by bracket feet or feet shaped like a turnip or a flattened ball. Occasionally, long thin pieces of wood called runners were applied underneath the full width of the front and rear to facilitate moving.

20 The frames of turned chairs, such as the Carver type, were held together with socket joints secured by wooden pins. The legs of these chairs were constructed of unseasoned wood which eventually shrank and held like a vise the seasoned rungs inserted into them. The frames of Chippendale- and Sheraton-type chairs, consisting of squared members, were held together with mortice and tenon joints which were also pinned or sometimes only glued. The seats were almost always made from solid pine boards fastened to the seat frame with nails or wooden dowels. These sturdy seats did not require the corner blocks common in cabinetmaker- or joiner-made furniture which had slip or upholstered seats.

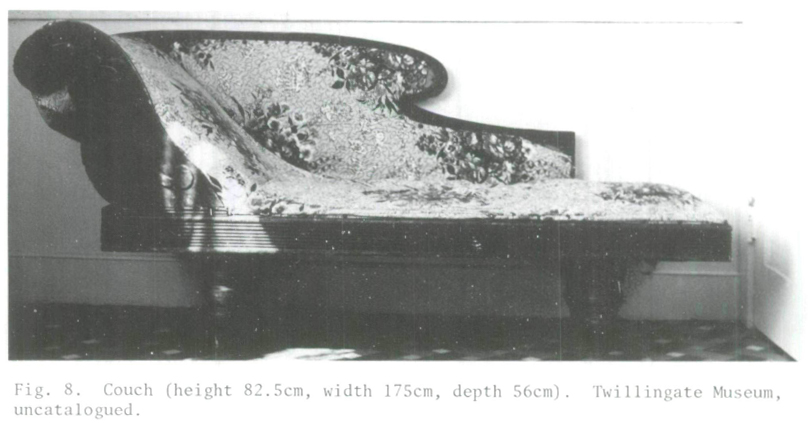

21 Sofas and couches were made with both squared and turned legs. Many had backs and seats of plank but some were upholstered. Coil springs were used in the seats of upholstered examples and both the seats and the backs were stuffed with straw or other flexible material. In one particular outport sofa examined, for instance, the stuffing consisted of the netting of a cod trap and various articles of clothing including a suit of men's long underwear. The upholstery material was usually painted sail cloth; fabric obtained from the merchant was used less frequently. A large pine sofa with birch legs (fig. 7) was constructed by Andrew Young in Twillingate, probably late in the nineteenth century. The piece has since been refinished and re-upholstered. The most striking feature of this example, apart from its size, is the shape of its back. Notice the shape of the back of a late nineteenth-century pine and birch couch from the same settlement (fig. 8). Possibly this couch or a similar one inspired the sofa's design.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 822 A piece of furniture might be the product of several people. For example, a skillful lathe owner would be called upon to produce legs, rungs, spindles, and various turned decoration such as pilasters and bosses, while a talented carver or grainer would also be employed to use his special skills.

Finishes, Decorations, and Hardware

23 After the furniture had been constructed, it was usually painted or grained to resemble the woods — mahogany, rosewood, or walnut — used in commercially produced furniture. Occasionally outport furniture, especially late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century examples, was given a dark stain and a clear shellac finish. Sometimes, however, furniture, particularly that used in the kitchen and in the bedroom, was painted in bright colours, chiefly red or blue. Most graining was done not, as one would expect, to produce an accurate imitation of wood grain, but rather for decorative effect, and seldom resembled any known wood,

24 As a general rule, the later the construction the more lavish the decoration. As the nineteenth century progressed, furniture was more and more adorned with turnery, carving, and other detail, so that by the beginning of the twentieth century many items were profusely decorated. This late, highly embellished furniture is most interesting because it represents a folk art still practised when the Europeans and other North Americans were buying factory-made furniture. But what makes this furniture particularly interesting is that the factory-made furniture clearly influenced the folk furniture in form and decoration. The early twentieth-century, commode-type washstand from Salmon Cove, Conception Bay, was made with few frills (fig. 9). This homemade piece, however, shows the marriage of an early twentieth-century style inspired by factory-produced furniture with a traditional folk decoration, the heart. This washstand, incidentally, was built from packing-case material.

25 Although hardware was essentially functional, several items also served as decorations. Wooden knobs were turned by lathe for use on the doors and drawers of case pieces. During the middle of the nineteenth century mass-produced white porcelain knobs were available and became popular. Other commercially produced drawer pulls, such as the late nineteenth-century pear-shaped handles, were also commonly used.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 926 Occasionally wood, brass, ivory, or mother-of-pearl was inset decoratively around the keyhole. In other instances wooden keyhole surrounds were applied and stood out in relief. During the second half of the nineteenth century, however, imported metal keyhole surrounds were mostly used. Other metal hardware, such as locks, hinges, nails, and screws, was imported. Some nails, however, were forged locally until well into the twentieth century. Hardware was also saved from older furniture and reused on new pieces. Consequently, it is not unusual to find hardware on some Newfoundland outport examples predating the furniture itself.

Conclusion

27 Newfoundland outport furniture is somewhat similar to early furniture produced in other rural areas of North America. Both were often inspired by English styles and, although a greater variety of wood was available and used for furniture making on the American mainland, both were frequently constructed from pine, spruce, or fir. Furthermore, both Newfoundland outport furniture and early North American rural furniture were commonly finished with paint or were grained. In fact, both were decorated with similar painted or carved designs and both used the same kinds of hardware. By the eighteenth century, however, most settlements on the American mainland had populations sufficiently large to support full-time furniture makers. Newfoundland did not reach this stage of development until after the first decade of the nineteenth century. Consequently, the proportion of furniture made by skilled craftsmen is smaller in Newfoundland than on the American mainland.

28 It is a mistake to evaluate Newfoundland furniture by standards used to evaluate that made elsewhere by furniture makers or in factories. Furniture created by Newfoundlanders for their own use clearly demonstrates not only the skills and peculiarities of these individuals, but also reflects the way of life, the ideals, and aspirations of a people. Furthermore, it shows that Newfoundlanders not only managed to survive in a harsh environment in semi-isolation, but lived enthusiastically and acted upon their environment with imagination

29 Newfoundland handmade furniture has generally been treated with considerable apathy by Newfoundlanders. The outport people maintain that this furniture reminds them of hard times, while Newfoundlanders living in the urban areas, such as St. John's, consider it to be of little value. While there is apathy, mainland pickers — locally referred to as junk men — regularly scour the outports and take away considerable quantities of furniture and other items. In fact, most of the local furniture that has survived is on the mainland, where much of it has been sold under the general label of Maritimes furniture or has been passed off as being anything from early American to early Quebec. Newfoundlanders must become aware of the value of their own furniture and of the extent of its continuing local depletion. It is unlikely that this essay alone will greatly affect the present situation, but it may create some interest and perhaps stimulate further research. There may yet be time to preserve what little remains of an important part of Newfoundland's heritage.

Display large image of Figure 10

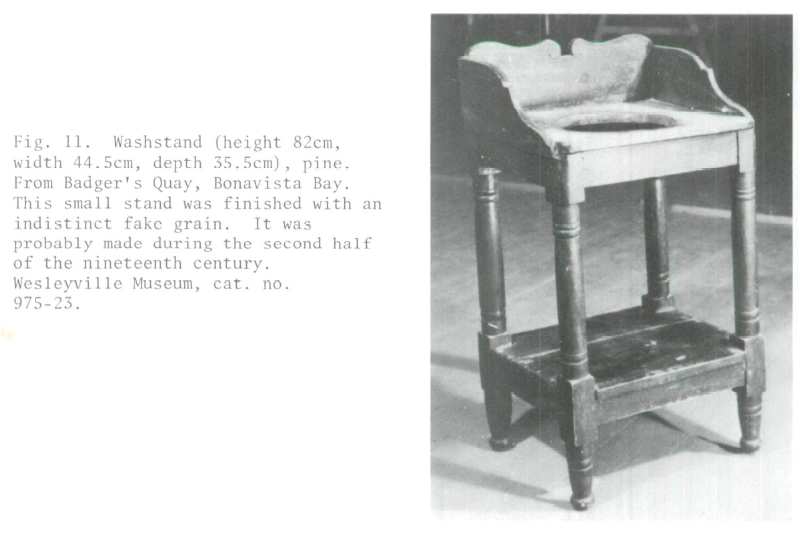

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15 Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16 Display large image of Figure 17

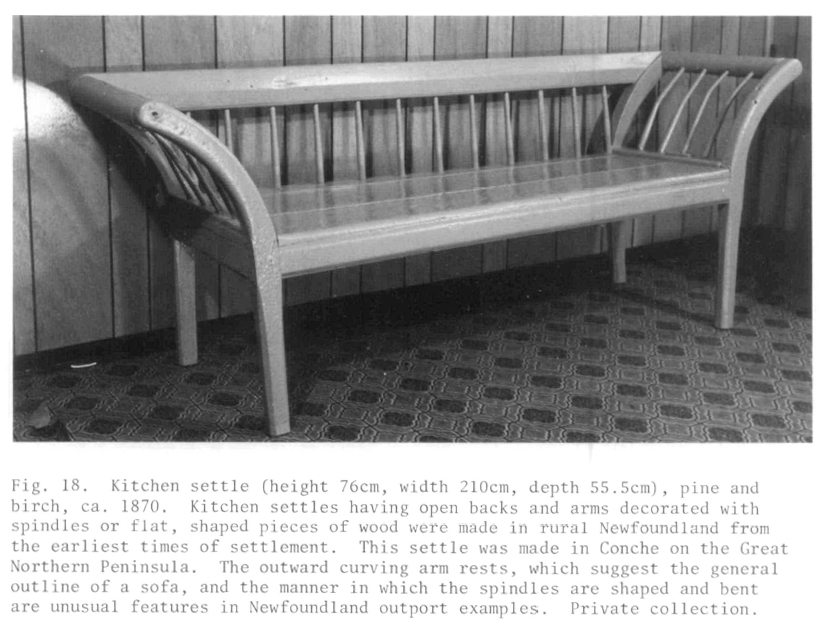

Display large image of Figure 17 Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18