Special Report / Rapport spécial

Computer-Based Archival Research Project:

A Preliminary Report

Grâce à la collaboration du Répertoire national des Musées nationaux du Canada et du Memorial University, le Newfoundland Museum a mis au point un fichier pour consigner les données tirées d'annonces de journaux du ⅪⅩe siècle. L'information ainsi traitée peut être versée aux ordinateurs du Répertoire national, puis retracée et analysée à l'aide de l'ordinateur. Le fichier est découpé en vingt-cinq champs dont neuf sont réservés aux marchandises classées d'après la publication de Statistique Canada intitulée Classification des marchandises pour le commerce du Canada. Comme l'information peut être retracée par tous les champs, les données ainsi informatisées peuvent servir à répondre aux interrogations les plus diverses des chercheurs.

Introduction

1 Nothing can be more frustrating or more rewarding to the researcher in material history than archival research. Canadian archives contain a wealth of primary and secondary sources which reveal to the diligent an immensely detailed picture of past mores, manners, and practice. Much of this wealth is as yet untapped; researchers are few and time scarce. Yet this exploration of the written documentation of the past is vital if we are to attempt to understand the world as our ancestors apprehended it.

2 In Newfoundland the case is particularly acute. The last general history of the province was written in the 1890s. Since then historians have for the most part concentrated on the unravelling of the province's complicated political saga, its economic position in Atlantic trade, or the development of its institutions. Only recently have certain geographers, folklorists, and material historians begun to research the social and cultural patterns of Newfoundland and Labrador. While studies in cultural geography or folklore are rare, published research in material history is almost non-existent. Shane O'Dea has compiled lists of native cabinetmakers and silversmiths; John Joy has examined the later nineteenth-century manufacturing base in St. John's in an unpublished M.A. thesis for Memorial University; and John Mannion's students have begun to look into the cloth trade and clothing. Perhaps the most extensive studies with a bearing on material history have been conducted by the Maritime History Group under Keith Matthews. Researchers have painstakingly transcribed thousands of shipping lists in order to build a picture of the Newfoundland trade.

3 When the Newfoundland Museum came to plan its new exhibits, however, staff discovered that little documentation existed on the collections themselves and secondary sources on material culture in Newfoundland were unavailable. Thus it was necessary to turn to primary archival documents for basic information on provenance, type, and date of introduction of goods imported or variety, type, and maker of goods produced in Newfoundland. John Joy had examined the directories and his thesis on manufacturing in St. John's was most helpful, but the directories began in the 1880s. Matthews's and Mannion's import lists were excellent but they were not as specific as the museum could hope. Probates were available, as were business ledgers, and the Geography Department had begun work on these. The museum decided to turn to the advertisements in Newfoundland newspapers to extract information primarily on commodities and services available in St. John's and other outport communities throughout the nineteenth century. As staff began to examine these sources, it became obvious that they were covering ground covered often before. Students had looked through the same tattered copies of the Public Ledger or the Carbonear Herald for information on the courts, on temperance meetings, on reports of scandal. Shane O'Dea had scanned the journals for native cabinetmakers and practising silversmiths. It became clear that after we had finished our work, yet another researcher would sift through the same material, looking for a slightly different set of data. Was there a simple mechanism by which much valuable research time could be saved and needless duplication of research efforts be eliminated? With this goal in mind we began to look closely at the computer services of the National Inventory Programme, National Museums of Canada, and the possibility that its programmes and our needs might indeed mesh.

The Use of the Computer in Archival Research

4 To many trained in the humanities the use of a computer in conducting research is anathema. There is a fear that the use of a machine will distance the researcher from the material, making the creative interchange that so frequently happens between the document and the historian impossible. The computer is, however, an accepted research tool in the social sciences and in archaeology. While it can never replace well-trained and curious human intelligence, it can act as a valuable tool for that intelligence, performing the menial and time-consuming research tasks that senior researchers normally delegate to graduate students and assistants.

5 It is important to understand the nature of the computer's function. The English word "computer" implies a machine that figures or thinks; the French term ordonnateur is perhaps more appropriate. A computer at its most basic is an orderer, an organizer of information. Its great advantage over the human organizer is its ability to digest immense quantities of disparate data and to order them in a seemingly endless variety of ways. This ability has obvious practical applications for the problems of archival research. If information from an archival source can be entered into a system where it can be indexed in numerous ways, the same body of material can serve more than one user.

6 This can be illustrated by returning to the use of newspaper advertisements in material history research. Different researchers will examine these for different purposes. One researcher may be interested in the variety of foodstuffs, both imported and locally produced, available in St. John's in 1814. Another researcher may be interested in the names of the local merchants who retailed food produce. Another may be concerned with the variation in foodstuffs imported over a thirty-year period from 1814 to 1844. All three researchers will use the data gathered to answer totally different questions. By placing data from these same advertisements into a standard computer format, it is possible to ask the computer to search the data set, retrieve the data relevant to each question, and organize it for the particular user. Once the data has been entered into the computer, the operations of retrieval and organization can be accomplished in a matter of seconds. Thus, instead of three graduate students wearily examining the same rolls of microfilm or yellowed, crumbling pages and producing three specific reports (none of which can be used to answer any questions other than those originally stipulated by the researcher), the same data base, entered once, can be indexed by the computer to yield not three, but countless answers to specific problems.

7 Researchers are, however, notoriously idiosyncratic. Could a single data base, properly indexed, really fulfill the needs of more than one researcher? It is important here to realize that, unlike the research report produced to answer a particular query, material entered into a computer is not entered according to specific end-use. Once a source has been decided, all data from that source are entered indiscriminately. No judgments are made at the point of entry; thus, all the material in the original source is available in the computer's memory banks. The researcher can then call up any of the information entered and in a variety of configurations. Returning to our example of the three researchers interested in various aspects of food consumption and marketing in nineteenth-century St. John's, we can illustrate this recall ability.

8 Below are two examples of typical advertisements (see Appendix 1 for copies of advertisements in computer print-out form):

Belding, Master, in 10 days from Halifax, and for

sale on board said vessel, lying at Messieurs Parker,

Bulley, Job and Company's lower wharf -

Prime Corned Beef in barrels.

Prime Fresh Beef in quarters.

Excellent Mutton in carcases.

Cider in hogs heads and barrels.

Potatoes, Turnips, Onions, Oats, Turkies and Geese Shingles.

(St. John's Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser, 13 January 1814)

36 quarter-chest of Very Superior Bohea Tea.

6 Boxes of 6 pounds each of Gunpowder Tea.

12 canisters of 2 pounds each of the Best Gunpowder Tea.

12 canisters of 2 pounds each of Imperial Tea

50 boxes of the Best English Starch

10 tierces of Carolina Rice.

25 firkins of Butter, put up for families

20 Goshen Cheeses.

50 Nova Scotia Cheeses.

(St. John's Times, 17 January 1844)

9 Researcher A, interested in the variety of foodstuffs sold in 1814, could ask the computer to search out all foodstuffs listed in such advertisements throughout the year and would receive a printout listing "prime corned beef, prime fresh beef, mutton, cider, potatoes, turnips, onions, oats, turkies, geese" and any additional items advertised that year. Researcher B, interested in local merchants selling food in 1814, would request a search and receive a list with the names of "Parker, Bully, Job and Company," etc. Researcher C, attempting to compare the variety of items imported over a thirty-year period, might ask the computer to print out all food items advertised every January and every July, every other year, beginning with 1814 and ending in 1844.

10 These are very simple retrievals. A research problem can be extremely complex. Researcher A may in fact want to compare what was sold in Carbonear with what was sold in St. John's and may also want to make a seasonal comparison over a five-year period. Researcher B may require not only a listing of merchants who sold local produce, but also a cross-index of specific merchants with specific kinds of produce. Researcher C may demand not simply lists of items but also a correlation with ports of origin and merchants over the thirty-year period. Admittedly none of these problems would be beyond the competence of three good researchers, but none could perform his searches as quickly as the computer.

The Development of a Computer-Based Format

11 Initial discussions with interested groups in St. John's, notably the Maritime History Group at Memorial and Parks Canada, indicated that a computer-based research format for advertisements could prove useful. The National Inventory was willing to explore the problem with the museum and to aid in the development of an appropriate format. The computer's strength is in its speed, efficiency, and versatility in sorting information; its limitation is its inability to go beyond the given. A computer can only retrieve what it has received. In order to retrieve data, it must receive information in a consistent manner. A computer cannot analyze idiosyncratic input. Thus, if a computer is to be asked to compare data (for example, the items sold in St. John's and the items sold in Carbonear), it must receive that data in the same manner.

12 The development of the format for recording information is obviously of prime importance in developing a workable system. A format must answer several criteria. It must be machine readable: in other words it must record information in discrete units, or fields, that can be indexed by the computer. Secondly, it must divide the information into as many fields as possible so that it can allow the computer to search a large number of fields and thus provide responses to as many different queries as possible. Thirdly, the format must be relatively simple to complete. If information must be encoded into a mathematical formula in order to be entered into the computer, the time-saving advantages of computer indexing are lost. Moreover, the information entered in code can only be retrieved in code and the process of decoding is also time-consuming.

13 The last criterion was easily satisfied. Canadians are fortunate that the National Inventory in Ottawa uses a computer programme which answers the need for simplicity of coding and retrieval of information. The ISIS programme is a word-based system of data entry. The Inventory uses this system to record information on artifacts and specimens held in various museum collections. One aspect of this programme, applied primarily to the cataloguing of information on works of art, was admirably suited to the recording of information in newspaper advertisements. In order to record subject matter in paintings, a syntactical system was developed. For example, in cataloguing a landscape painting the cataloguer chooses the primary subject matter, "waterfall," and that word becomes the prime term. This is the term which describes in general the content of the painting. This is particularized by the addition of descriptive phrases after the prime term, separated from it by commas, the whole description ending with a period. The computer "reads" the first word entered as the prime term, understands the words following the comma as secondary descriptive terms, and recognizes the period as the end of the description.

14 This method of recording works admirably with advertisements. Take, for example, an advertisement for 100 pounds of the finest quality lemons appearing in a St. John's newspaper of 1850. The researcher records "lemons, 100 pounds, finest quality." Anyone looking for the occurrence of lemons can simply search for the prime term "lemons." There is no necessity to code for lemons or to add informative terms as in "fruit; lemons."

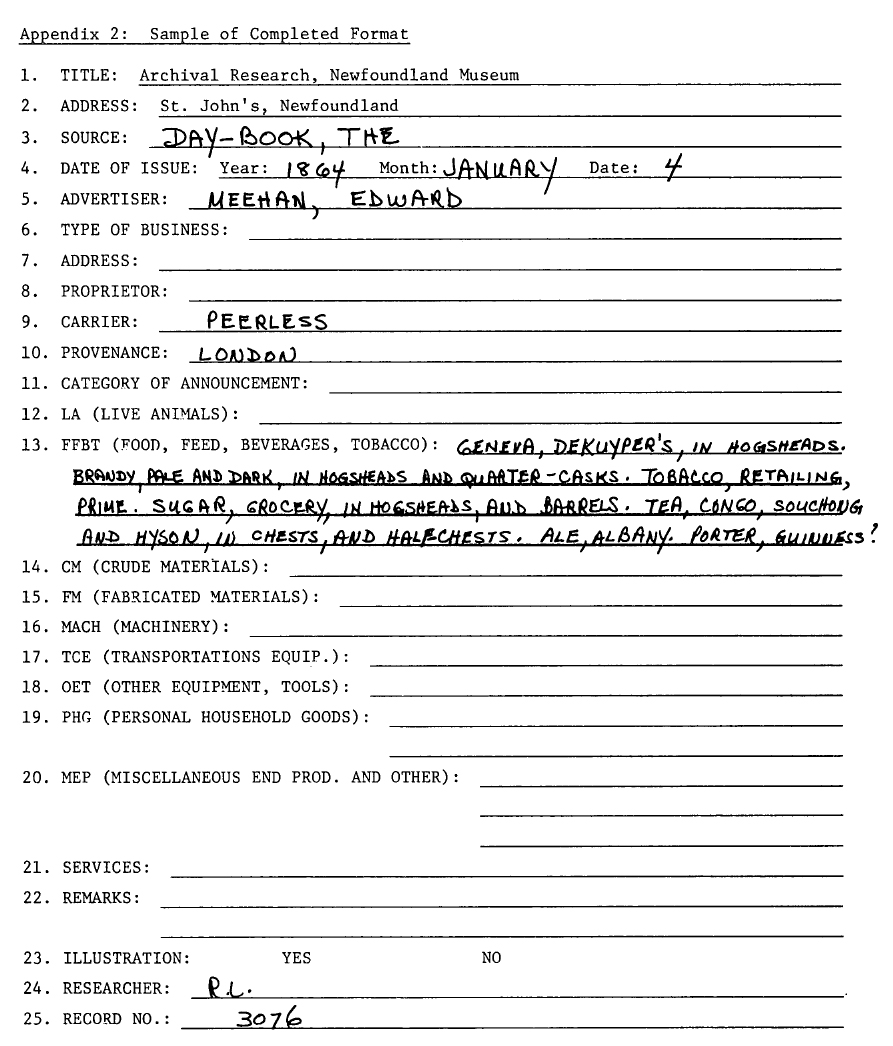

15 Once it had been ascertained that this descriptive system would record information from advertisements without enormous difficulties, it was then necessary to decide on the kind of information to extract and the number of fields into which this information would be placed. Though the interest of the museum was in the commodities themselves and the date of their appearance, it was recognized that other users might be interested in different types of information appearing in the advertisements, such as the name of the importing merchant, the vessel which carried the goods, or the appearance of an illustration in the text. Trial and error produced a draft format of twenty-five fields. An initial test run of 100 advertisements produced some modifications in the original design, but the present revised format (see Appendix 2) has worked very well.

16 From the information recorded one can learn the name of a merchant, the location of his business, the type of his business (for example, commission merchant, merchant-retailer, auctioneer), the vessel on which his goods arrived, the provenance of the shipment, whether or not he was advertising a new shipment, a fire sale, or a spring clearance, and the quantity, quality, and very often the precise colour and style of what he sold. Similarly the format can record the items offered for sale at an auction or the services advertised by a local craftsperson. Interesting tidbits of information, such as the fact that fish or oil can be exchanged for goods or that the merchant caters specifically to the outport trade, can be entered in field 22 under "Remarks." It must be emphasized that there is no restriction on searching; the format can be searched on all twenty-five fields. For example, if a researcher were interested in a particular vessel, the Cluthia, he could request a search on field 9 ("Carrier") for the incidence of the Cluthia as a carrier. (The museum, which has several watercolours of this vessel, is requesting such a search. Together with enlarged photographs of the advertisements located by the computer and a copy of shipping lists, the paintings will appear in an exhibit on the Newfoundland trade.) The chief problem to be overcome in format design dealt with what the museum considered to be the most interesting information - commodities and services. The resolution of this problem has enhanced the usefulness of the data stored. Even before the test run it became obvious that a major difficulty was the initial categorization of the seemingly endless commodities listed in the advertisements. To have listed all commodities as prime terms under a single field ("Commodity") would have required the researcher interested in foodstuffs to search for an endless number of specific items. It would have been impossible to request a listing of all food items sold in one month, since it was unlikely that the researcher could have pinpointed precisely the items sold.

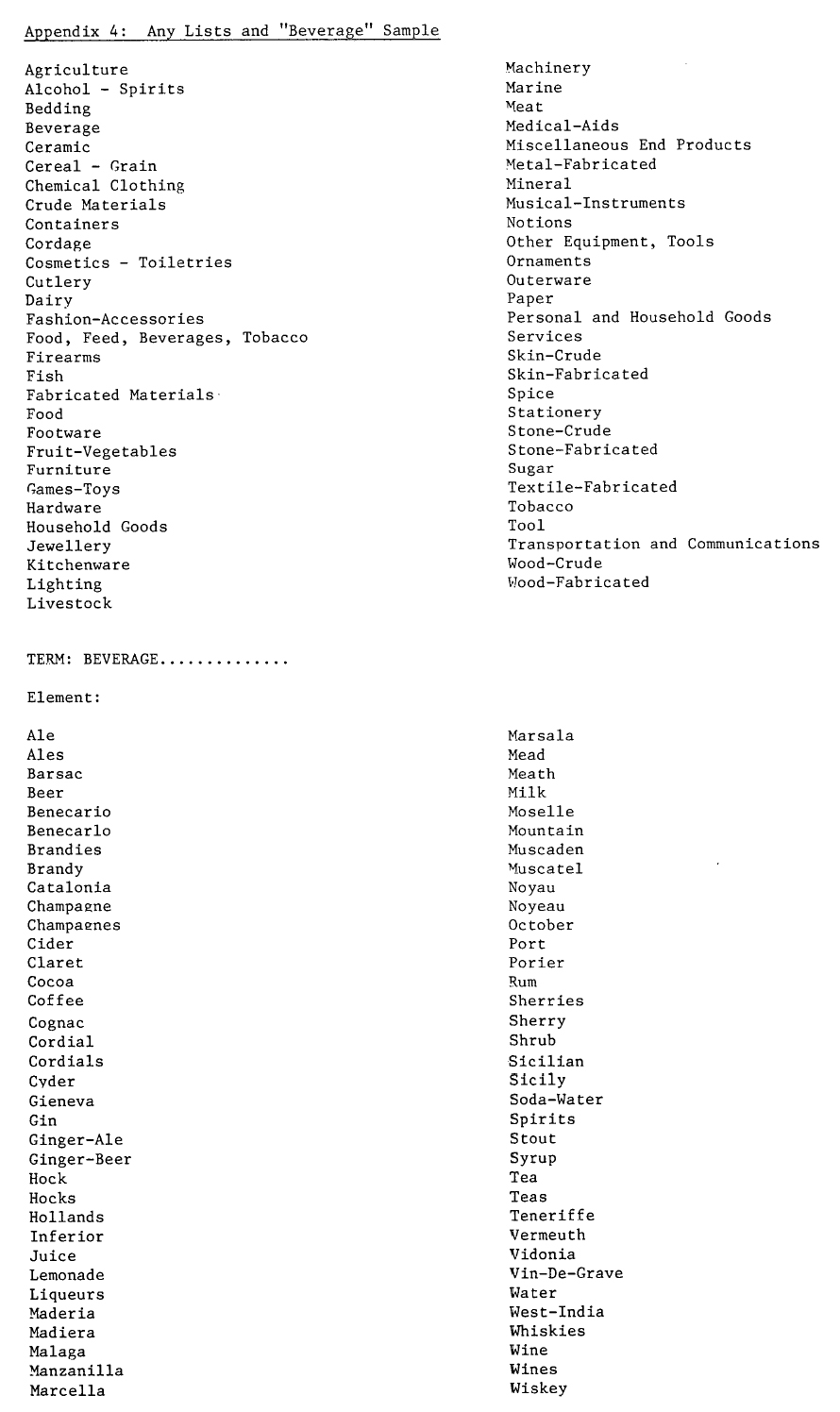

17 This problem resolved itself very neatly around a suggestion made by David Alexander of the Maritime History Group. The format utilized the broad categories compiled by Statistics Canada in its "Trade of Canada Commodity Classification." In order to analyze present import-export patterns, Statistics Canada has devised a number of general categories under which an unbelievably disparate selection of goods may be subsumed. Museum and National Inventory staff modified this system slightly to reflect nineteenth-century goods and developed the following nine broad categories for commodity classification:

FFBT (Food, Feed, Beverages, Tobacco)

CM (Crude Materials)

FM (Fabricated Materials)

MACH (Machinery)

TCE (Transportation and Communications Equipment)

OET (Other Equipment, Tools)

PHG (Personal Household Goods)

MEP (Miscellaneous End Products and Other).

We also added a "Services" classification to record the announcements of photographers, music teachers, hairdressers, cabinetmakers, and so on. The Statistics Canada classifications have proven very satisfactory and though specific goods differ it is possible to refer to the Statistics Canada expanded lists if in doubt as to the very general category in which to place an item. Since the formats are relatively consistent, this solution has also made possible the comparison of nineteenth-century imports with contemporary imports through computer indexing.

Application of the Format

18 With National Inventory assistance the museum was able both to test and to use the format as a research tool. Deborah Jewett of the Inventory analyzed a test run of 100 advertisements and assisted in the revision of the format; she also co-ordinated the development of ancillary materials - "Any Lists," glossaries, instructions - necessary to the actual project. The museum was fortunate in hiring, with the Inventory's help, a Canada Works summer team. This team was led by Valerie Kolonel, a history graduate from Memorial University, who managed four researchers and a data entry operator over a four-month period, May - September 1979.

19 As the first newspaper in Newfoundland was published in 1806, it was decided to record advertisements appearing from that date to 1900. This required the analysis of some 43 newspapers from St. John's, Carbonear, Harbour Grace, Heart's Content, and Trinity. Most were available on microfilm or in bound volumes at the Provincial Archives or Memorial University. During the summer the researchers recorded between 40 and 60 advertisements per day, completing 6,979 formats in all, while the data entry operator entered 2,625 of these into the computer. (Data entry is continuing at the museum.) The newspapers and the years covered are listed in Appendix 3 and a completed format is shown in Appendix 2.

20 In addition to managing the group the co-ordinator was also responsible for the compilation of glossaries and, with the help of the Inventory, of Any Lists. It became apparent as work progressed that descriptive terminology for goods and some services had changed radically since the nineteenth century. To ensure that an item was recorded in the correct field, the co-ordinator was obliged to develop extensive glossaries which researchers might consult. For example, what were "Norway rags?" Should they be placed in field 15 ("Fabricated Materials") or field 19 ("Personal and Household goods")? (They are cutstones for building.) Abbreviations for items or weights and measures were often obscure. These too are included in the glossaries, along with their contemporary equivalents.

21 One of the most important aids for the user are the Any Lists. Almost sixty such lists were developed to group similar commodities under broad headings. For example, one of the Any Lists for field 13 ("Food, Feed, Beverages, Tobacco") is "Beverages." This list includes the prime terms entered on the format, for example, rum, muscat, muscatel, vin-de-grave, cider. Thus, a researcher interested in any beverage advertised in 1831 in St. John's can request the computer to search field 13 for "Any Beverage" and receive a printout listing all the advertisements containing any one of the specific beverages included on the Any Lists. The list also allows the researcher to make a quick check to see if the item in which he is interested has ever been recorded. If "cider" does not occur as a prime term on the Any List for beverages, then no incidence of cider has been recorded in an advertisement. Any Lists also include alternate spellings, if they have been recorded as prime terms, for example, "carraway," "carroway." The flexibility of the Any List eliminates the need for the researcher to decide on the correct spelling of a prime term; the item can be recorded exactly as it appears in the source. It should be noted, however, that if all occurrences of an item have been recorded in one spelling, for example, "trowsers," the contemporary researcher who requests a search for records of "trousers" will be disappointed. The computer cannot recognize the difference in spelling although it will compensate for incidents of plural and singular records. An Any List for beverages plus a table of all available Any Lists appears as Appendix 4.

Retrieval and Potential Use

22 Material entered into the computer can be retrieved in a variety of ways, the simplest being a printout of the records. The Newfoundland Museum has printouts of all records entered. These and the Any Lists have already been used by a number of researchers with simple requests such as "Do you have any records of advertisements for aerated water?" More complicated requests for cross-indices, lists, and so on are best answered through a direct request to the computer. If, for example, a researcher wanted to know the types of beverages available in 1831, he would request a search on field 4 for "1831" and on field 19 for "Any Beverages." The computer would then produce a printout of the advertisements for beverages in 1831. The actual mechanical process is slightly more complex, since it involves the terminal operator's ability to phrase the question correctly to the computer. But the printout itself is verbal and immediately accessible to the researcher. The researcher familiar with a terminal can in fact request the information to appear on the terminal screen, make the requisite notes, and then request a printout of the particular items desired. The retrieval process can also be very specific. If a researcher is interested in à particular item, such as Belgian carpets, he can request a search in field 19 for "Carpets, Belgian" and receive any instances of this item.

23 A researcher using this system has available literally at his fingertips a vast body of information, retrievable almost instantly. The information can be cross-indexed automatically to correlate particular merchants with particular goods, vessels with merchants, provenance with commodity. Items can be grouped by year, lists of particular items generated, craftspeople enumerated. It would be a mistake, however, to view the information thus retrieved as providing the ultimate authority on the subject. If a search reveals no Belgian carpets in 1831, that does not necessarily mean that no Belgian carpets graced the salons of St. John's in that year; it just means that they were not advertised. A computer-based system such as this is simply a tool, useful to the researcher. Information from this system combined with that from ledgers, probates, diary and journal accounts, and the artifacts themselves, can help to build up a more complete picture of the past. The computer cannot substitute for careful research, only assist it.

24 With the co-operation of the National Inventory Programme and the sponsorship of Memorial University, Valerie Kolonel and museum staff are presently experimenting with the system and compiling a user's guide which is expected to be available this summer. Although the system is operable, it is at present limited by an incomplete data set and further work will be required to analyze all nineteenth-century newspaper advertisements. (It may seem fruitless to record every advertisement for 100 years, but it should be noted that the only reference to the work of the daguerrotypist, A. Salteri of Halifax, in Newfoundland, occurs in one entry in 1852 in a Carbonear paper. Prior to the location of this entry, his presence could be inferred, but not proved.) Possibilities also exist for expansion of the computer-based format to record ledgers and probates as well as for the development of programmes to compare computerized shipping list data, as recorded by the Maritime History Group, with computerized advertisements.

25 In the final analysis it must be determined whether the effort required for recording and entry of information is worthwhile. This will only be truly proven through further experimentation with this preliminary study. Already, however, users of this first rough system have given encouraging reports. The use of the system is not limited strictly to research papers, but has applications in the exhibition and restoration field. The museum uses the information to locate appropriate graphic material to complement artifact exhibits. Parks Canada and the Provincial Historic Sites branch see the system operating as a "shopping list" to aid in determining period furnishings. Similar studies in other Atlantic provinces may eventually provide a computer-indexed picture of food habits, styles of dress, and patterns of service provisions. The Newfoundland Museum and Memorial University welcome any enquiries or comments concerning the project and will be delighted to send further information.

26 Please address all enquiries as follows:

c/o Newfoundland Museum

285 Duckworth Street

St. John's, Newfoundland

A1C 1G9

Appendix 3: List of Newspapers covered to date

- Morning Post and Shipping Gazette1850, July 11

- Weekly Herald and Conception Bay General Advertiser1845, January 1-15

- Pilot1852, February 28 - 1853, February 12

- St. John's News (North Star)1872, August - November1873, February - May, November (North Star)

- Star and Conception Bay, Semi-Weekly Advertiser1872, June - October, December1873, February, May, July, August, October, November, December

- Star and Conception Bay Journal 1834, July, August, October - December1835, January, April - December1836, January, February, May - July, September - December1837, February, April - July, September - December1838, January, February, April1839, January, May, July, September - December

- Star and Conception Bay Weekly Reporter1873, February - October

- Carbonear Star and Conception Bay Journal1833, January, February, April - December

- Conception Bay Man1856, September - 1858, May - December

- Patriot and Terra Nova Herald1849, January, April, May, September - December1850, February - May, September, December1851, April - June, September1852, April - May, August, September, November, December1853, February- April, September -1854, June, September -1855, February, May, June, November -1856, June, August - December

- Daily Tribune1893, January - August

- Day Book1862, January1864, December

- Evening Mercury1886, January - July

- Newfoundlander 1827, August - November1843, March 30

- Times1843, January, November1844, January, July -1845, January, September - December1848, August 21849, January1850, August -1851, April 23 - 13 September -1852, July 10

- Evening Herald1890, January 13 and 14

- Newfoundland Express1851, October 21 - 1852, April 201852, November - 1853, February 261852, September 30 - November 131852, April 20 - September 28

- Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser1810, April - December1811, January, February, June, August, October1813, September - 1814, November1813, February, March, April, May, 5 August1814, December1816, July - December18[18], October1815, July 13 - October 51815, October 5 - December 71814, December 8 - 1815, July 131817, January 14 - 1817, July 11817, July 1 - October 21

- Newfoundland Mercantile Journal1816, September, November - 1817, June1818, January - October1818, October 8 - 1819, February 111819, February 18 - May 61819, May 6, August 261819, August 12 - 1820, April 201820, April 27 - September 28

Appendix 5: Sample of Glossary: Clothing/Fabric

1) Peruvian quadruped: a species of llama, having a long, wooly, fur hair.

2) Alpaca wool; also the fabric made from it.

Loosely woven cotten or wool fabric in a plain weave made with soft twist filling yarns and closely napped to imitate felt. It is dyed in solid colours, usually green. It was originally made in Baza, Spain, with coarse woolen warp and filling yarns, heavily felted, and finished with a long nap on both sides; it was later made thinner and finer and was used for clothing, when warm knitted underwear was unknown. (Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Gauze-like, silky dress fabric, originally made at Bareges. (Oxford English Dictionary)

Leather apron.

1) Heavy-fulled, twilled wool double cloth which resembles Kersey. The face is a fine wool napped and sheared to produce a smooth, dense, curly nap. Called beaver cloth.

2) Silk plush with a flat pile, used for hats.

3) Heavy cotton double cloth napped strongly on both sides. It is made with a fine, hard twist warp and coarse slack twist filling, and is often printed. (Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

A hat of the best kind; the part of a helmet that covers the face.

A term formerly applied to a type of slate-coloured linen which was beetled during its manufacture. Also spelled BLAY linen.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Silk net used for frills and ruffles.

Strong leather half-boot.

Fine cord in haberdashery.

(for BOMBAZEL) Name given to two sorts of stuffs, one of silk, the other crossed of cotton. Also BOMBAZET. Twilled fabric of silk and worsted or cotton.

(Webster's)

Twilled dress material composed of silk and worsted, cotton and worsted, or worsted alone. In black, much used in mourning.

Plain weave, coarse cotton fabric.

Suspenders, the straps that sustain pantaloons.

Fabric decorated with special threads into the warp or weft.

Coarse stout sort of shoe.

1) Thick, heavy, durable woolen fabric made with an eight-harness satin warp-face weave. The fabric is napped, thoroughly fulled and sheared to produce a smooth face.

2) Carded cotton yarns in a five-harness filling face satin weave produce a thick, smooth finish fabric used for outerwear.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Covering for the foot or leg, reaching to the calf or to the knee; a half-boot.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Woolen stuff of fine gloss, and checkered in the warp.

Name originally applied to some beautiful and costly eastern fabric, afterwards to imitations and substitutes the nature of which has changed many times over. A kind of stuff originally made by a mixture of silk and camel's hair; it is now made with wool and silk. A light stuff formerly much used for female apparel, made of long wool, hard spun, sometimes mixed in the loom, with cotton or linen yarn.

Twilled fabric with silk warp and woollen filling woven on a jacquard loom to form a design with the silk yarn. Originally made in the middle of the nineteenth century at Sedan, France, and later imitated in cotton.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Also Kerseymere. A medium-weighted woolen cloth of soft texture. (Webster's New International Dictionary.

Term used in Peru for coarse homespun or imported woolen fabric with a long nap. Used locally for shawls and cloaks.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Bodice, more or less like the upper part of a chemise.

2) An article, usually of lace or muslin, made to fill in the open front of a woman's dress. Also CHEMISETTS.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Term derived from the French for "caterpillar." Refers to:

1) Special yarn with pile protruding on all sides, produced by first weaving a fabric with cotton or linen warp and silk, wool, or cotton filling; the warps are taped in groups of four and the fillings are beaten in very closely; after weaving, the fabric is cut lengthwise between each of these groups of warp yarns, each cutting producing a continuous chenille yarn which is then twisted.

2) Fabric woven from chenille yarns.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Ball of thread, yarn, or cord.

2) Lower corner of a square sail or the after lower corner of a fore-and-aft sail.

(Webster's Third New International Dictionary)

Yarn dyed fabric made of wool and cotton with a diagonal weave.

Large loosely knitted head scarf.

(Webster's New International Dictionary)

CLOUD YARN: Another name for Flake or Bunch Yarn or Slub Yarn, both novelty yarns with uneven finishes.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Cloth for coats; as merchants advertise an assortment of coatings.

Thin fabric of worsted and cotton or worsted and silk used for hat bands, etc.

Silk handkerchief with characteristic Indian pattern; plain, undyed.

Worsted fabric made with a corkscrew weave. The warp appears on both the face and the back of the fabric, obscuring the filling and producing a warp rib across the cloth at a low angle. The best grades have a French yarn worsted warp while the filling may be of wool or cotton. Uses: suiting, overcoating, etc.

Originally a lightweight, plain weave wool, French fabric, dyed in the piece.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

French term for plain weave, bleached linen fabric of medium quality. Uses: general household purposes.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Fine quality, medium weight, compactly woven wool fabric with a smooth, short napped, dress face finish; high count, high twist yarn is employed in a five-or eight-harness satin weave. Uses: trowsering, coating, riding habits, uniforms.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Woman's wrap like a cape, in vogue in the nineteenth century. With wide sleeves and cut in one piece with the body.

Fancy twill weave in which a continuous right hand twill is crossed by a left hand twill.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Strong, coarse, half-bleached linen fabric made in England, Ireland, and Brittany and used locally for many years by the lower classes for towels, shirts, etc.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Coarse, felted fabric made of wool, cotton or jute, or mixtures of these fibers, and napped on one side; it may be printed on the face. Uses: floor coverings.

2) Obsolete, English fabric woven with a worsted warp and woolen filling in a plain or twill weave of corded effects; the cloth was also ripped. Produced in the eighteenth century. Also spelled Droguet.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Species of coarse cloth or canvas used for sails, sacking of beds.

(Webster's Dictionary)

Strong, thick woolen fabric, well-felted, sometimes having a glazed appearance. Produced in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Also called Durant, Duretty.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Species of duck, Somateria mollissima, of northern regions that lines its nest with eiderdown.

2) The down itself.

Kind of veil worn by women.

Stout, thick woolen cloth, used chiefly for seamen's coats, also as a covering for port holes, the doors of powder magazines, etc.

1) Slit in the side of a robe, a pocket-hole.

2) Remnant of cloth.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

1) Lightweight, plain weave silk lining fabric with warp and filling yarns equally spaced. Made with single warp and sometimes made partly with wool.

2) Obsolete woolen fabric made in Florence.

3) Corded barege or grenadine used for women's clothing in England in the nineteenth century.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Kind of rough and thick woolen cloth, first made at Flushing.

1) Coarse cotton fabric used for servant's clothes in Scotland.

2) Spun yarn of woolen character made in Scotland in fancy mixtures. Uses: knit outerwear, tweeds.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

obsolete form of galosh.

GALOSH, GOLOSH: In later use an overshoe (now usually made of india rubber) worn to protect the ordinary shoe from wet or dirt.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Also GALOSH, GOLOSH, v. To furnish (a boot or shoe) with a galosh. Hence GALOSHED ppl. a.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Woman's blouse copies from the red shirt worn by the Italian patriot Garibali.

The material which garters are made of.

Cloth or leather having a smooth surface with high polish.

Coarse English shirting made with grandrelle yarns in a five-harness warp satin weave, generally with coloured warp stripes. Uses: work shirts.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Fabric made of hard twist yarns in a leno weave; it is an open weave dress fabric made of hard twisted cotton, silk or wool. Several dents are left empty, creating open spaces, and several warps are then placed in one dent to form stripes, checks or other patterns. Sometimes called black lenos when woven with black filling.

2) Fine, stout, hard twist silk yarn used in hosiery and laces.

3) Fine loosely woven fabric, plain or with woven dots or figures, is called curtain grenadine.

4) Table linen damask made in France.

5) Black silk lace worn in France in the eighteenth century.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

(originally made on the island); a closefitting knitted woolen shirt, worn by seamen.

(Webster's New World Dictionary)

Term for a fabric made of wool and cotton produced in Switzerland about the middle of the nineteenth century.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Also, bookbinding with cloth sides and leather back (bound in half-cloth).

Loose, soft cotton or linen toweling woven in a bird's eye or honeycomb pattern. A slack twist and low count weft forms long filling floats and a strong selvage. Small filling floats form the pattern on the face of the cloth.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Vivid purplish red.

(Webster's)

Possibly also a fabric.

1) Fine, sheer cotton dress fabric thinner than cambric. Originally made in India.

2) Plain weave cotton, gray cloth made in a wide variety of qualities, widths, and lengths. Also spelled JACONNET, JACONNETTE, JACONNOT.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Term used at one time for JEAN.

JEAN:

1) Warp faced, three-harness cotton twill generally woven of carded yarns in weights lighter than drills.

2) British term for a filling faced one up, two down twill cotton used for linings.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

TAHR or THAR:

Himalayan beardless wild goat having thick short recurving horns and a dark reddish brown mane.

DOWN:

Soft fur fiber usually from the undercoat of an animal.

(Webster's Third New International Dictionary)

1) Woolen fabric, face finished with a highly lustrous, fine nap. It is fulled more and has shorter nap than beaver, and about the same weight as melton and beaver. Durable; uses: overcoating and uniforms.

2) Diagonal ribbed or twill fabric, coarse and heavily fulled, either woven all wool or with a cotton warp and woolen weft. It takes its name from the English town of Kersey where it was made in the eleventh century.

Part of a garment or dress that hangs loose.

(Webster's)

Fine, plain weave, relatively sheer cotton fabric made in close constructions. The fabric has more body than voile. It is bleached, dyed, or printed. Uses: women's and children's dresses, blouses, underwear, pajamas and handkerchiefs. Sometimes called Batiste or Nainsook. The term lawn originally was used for fine, plain weave linen fabric with an open texture. This fabric is now designated as linen lawn. The word is derived from Laon, a city in France, where linen lawn was manufactured extensively.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Mechlin-type lace manufactured in Lyons, France. Hand-run silk or mercerized cotton outlines the design.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Fancy English alpaca fabric used in the nineteenth century.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Kind of cloak or loose garment to be worn over other garments.

British term for fine cotton pique made in a variety of qualities and patterns. Used for bedding in England and sometimes was quilted and used for dress shirt fronts.

Stiff cotton fabric similar to pique. Also Marseillesquilting.

1) Variety of sheep prized for its wool, originally bred in Spain.

2) Soft woolen material like fine French cashmiere, originally of merino wool.

3) Fine woolen yarn used for hosiery.

(Oxford)

Articles made or sold by milliners.

MILLINER:

Vendor of "fancy" wares and articles of apparel, esp. of such as were originally of Milan manufacture, e.g. "Milan bonnets," ribbons, gloves, cutlery (obs.). In modern use, a person (usually a woman) who makes up articles of female apparel, esp. bonnets and other headgear.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Abbreviation of alamode.

ALAMOMODE:

A thin, plain weave, glossy, lightweight and soft silk fabric, usually dyed black. Made first in seventeenth century England and France and used throughout the eighteenth century. Its early uses were in women's hoods and men's mourning scarves; more recently, it has been used for scarves, linings and millinery. Also spelled ALLAMOD.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Heavy, strong, cotton fabric woven with coarse, carded yarns; a high number of picks gives a smooth, solid surface. An eight-harness filling face satin weave, with two ends weaving as one, is generally used, and the fabric is given a short nap or sheared to produce a suede-like finish. The term is derived from molequin, the Arabian name for an old fabric. Uses: work and sport clothes. One variety is known as BARRAGON.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Heavily fulled, plain cloth having the shortest nap in the group of face finished woolens. It was originally all wool, or cotton warp and woolen weft. Made with a tight construction and finished to conceal all trace of the warp and weft, it is a completely smooth fabric. It takes its name from Melton, England, where it was first made, and is used for overcoatings and uniforms.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Short close-fitting jacket, such as is worn by sailors.

Plain weave heavy fabric made in Great Britain. The face is ribbed in the direction of the filling, and given a moire finish; the back is smooth and lustrous. Made of hard spun worsted yarn, and also cotton. When made of cotton, polished yarn is used in the filling. Used for upholstery and formerly for skirts.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Soft, thin fabric made of very fine yarns in a plain weave, and bleached or dyed pastel shades. Cotton or silk or combinations of these yarns are employed. Uses: millinery, dresses. Also called MULMUL.

1) Fabric similar to nankeen but more loosely woven.

2) Fine, dyed percale.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Closely woven lining or dress goods with a two-ply cotton warp and bright wool or worsted filling. Made in a plain weave or sometimes in a five-harness twill, the fabric has approximately twice as many picks per inch as ends. The filling completely covers the warp. The cloth was made first in Orleans, France, about 1837, and was crossdyed; later made in Bradford, England. Also called LUSTER ORLEANS and ORLEANS CLOTH.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Species of coarse linen imported from Osnaburgh in Germany. Also called OZNABURG.

Loose outer garment, coat or cloak, for men or women.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Suiting or dress fabric of cotton warp and worsted filling.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Nineteenth century English fabric with cotton warp and worsted filling and often woven with dobby figures. PARISIENNE: Figured Orleans popular in France and England in the middle of the nineteenth century.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Any of various kinds of footware, as a wooden shoe; a shoe with a wooden sole; a chopine, etc. to protect the feet from mud or wet.

A garment of fur; a long mantle or a cloak lined with fur. Or, a long mantle of silk, velvet, cloth, etc. worn by women, reaching to the ankles and having arm-holes or sleeve. Or, a garment worn out of doors by young children over their other clothes.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

(Corruption of PENISTONE.) A kind of coarse, woolen cloth formerly used for garments, linings, etc.

A fine, lightweight, plain weave silk lining fabric printed with large floral patterns. Used in England since the eighteenth century. Sometimes called PERSIANA.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Name for a fashionable overcoat or breeches, formerly fashionable; also for the cloth of which some overcoats are made.

2) Thick kind of ribbon or ribbed or corded silk used for hat bands.

Heavyweight, coarse, woolen overcoating generally made with a four-harness twill weave, well fulled, and finished with a nap on the face. Dyed navy blue or other dark shades.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Obsolete English kersey.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Close-fitting jacket worn by women, usually knitted.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

1) In early times, a piece of linen or silk cloth of any shape which was spread over or on an altar in a church.

2) Later, a wool or velvet cloak or outer garment spread over the shoulders.

3) Wool, velvet, etc. fabric. Uses: a cover over furniture, coffin, hearse.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Durable, plain weave, class of fabrics having fine cross ribs produced by employing warp yarns that are considerably finer than the filling yarns with about 2 or 3 times as many ends per inch as picks. Made of silk, cotton, wool, or a combination of these. Originally made with silk warp and wool filling.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Coloured handkerchief originally made at Pulicat; later (from 1785) a material made in imitation of these, woven from dyed yarn; also pullicate handkerchiefs, a checked coloured handkerchief of this material.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Term used in Jamaica, West Indies, for a type of fine bleached cotton shirting.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Ribbon, strip of lace or other material gathered into small cylindrical folds resembling a row of quills. Trimming fabric.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

RAVEN-DUCK (ad. G. rabenduch): a kind of canvas (also RAVEN'S duck).

(Oxford English Dictionary)

1) Striped or checked British cotton fabric made in the two up, one down warp face twill weave. Uses: boys' suits, wash dresses, aprons.

2) Woolen fabric made in equally wide blue and white stripes or gray and another colour stripes. Also called REGATTA STRIPES.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Dark grayish olive green to black.

(Webster's Third New International Dictionary)

Silk or cotton square or handkerchief; a thin silk or cotton fabric with a handkerchief pattern.

Rough towel used for rubbing the body after a bath.

Breadth of silk of about two yards long, it is gathered round the neck. Kinds: broad, circular collar, plaited, crimped, or fluted.

(Webster's Third New International Dictionary)

Coarse woven material of flax, jute, hemp, etc., used chiefly in the making of sacks and bags. Also, a piece of such material.

Plain weave, strong, piece dyed British cotton fabric finished with a high luster. Often calendered to produce a twill effect. Uses: linings and other purposes.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

1) Obsolete, thin, fine silk fabric with a soft finish, made in plain or twill weaves. Used in England chiefly for linings.

2) Plain weave, thin silk ribbon. Also spelled SARCENET, SARSNET, and SARSANET.

Also SARSNETTS.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Heavy weight woolen coating.

Ribbed woolen fabric.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Soft, luxurious, woolen or worsted fabric with lightly napped surface, made in England and particularly Scotland. Botany or merino quality of carded yarn is used, and a two up, two down twill weave is generally employed. The fabric was originally developed in Saxony, Germany. Also called Saxony flannel.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Serge fabric is mentioned as early as the twelfth century, applied to domestic use such as curtains and hangings, and for coarse articles of dress. The fabric was originally silk, later wool mixed with silk. Serge is a clear finished fabric characterized by the flat wale that crosses from the lower left to the upper right selvage on the right side of the fabric; made with a two up, two down twill, in which two warp yarns pass over one filling yarn, and the next two warp yarns pass under the same filling yarn. Woven in many weights and constructions from wool, cotton, silk, and various combinations. Used for clothing.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Light twilled woolen fabric used chiefly for linings.

Fabric in plain weave characterized by a slightly irregular surface that is due to the uneven slubbed filling yarns of wild silk or other fibres. A silk cloth with rough, knotted surface made from the wild silkworm.

(Webster's Third International Dictionary)

Fine linen or cotton fabric. A cotton lining fabric with a glossy finish usually, converted from a filling twill and given a friction calender finish. Originally made in Silesia, Germany.

Watered cloth of wool and silk, similar to poplin.

Outer garment as a loose jacket, tunic, cassock, mantle, gown or smock-frock. Wide baggy breeches or hose; loose trousers especially those worn by sailors. Ready-made clothing and other furnishings supplied to seamen from the ship's stores; hence, ready-made, cheap or inferior garments generally.

As in the sole of a shoe.

Stiffening, a general term for any agent employed to impart stiffness to material. Starch, or resins.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Something that stiffens, as a piece of stiff cloth in a cravat.

(Webster's New International Dictionary)

Man's coat to be worn over his other garments; outer coat worn during the Middle Ages.

Fabrics resembling flannet.

(Webster's Third International Dictionary)

General term for various fabrics with a soft surface or soft nap. Thick, closely woven, British wool fabric similar to flannel. Uses: work clothing. English fabric made with worsted warp and woolen filling in the eighteenth century. English translation of peau de cigne (lustrous, heavy silk fabric with a pebbled effect; made of crepe yarns in an eight-harness satin weave).

Watered cloth of wool and silk, similar to poplin. spelled TABINETT.

Narrow garment or covering for the neck worn by females. now made of fur but formerly of cloth.

Thread or cord composed of 2 or more fibres or filaments of hemp, silk, wool, cotton or the like, wound round one another; in cotton spinning, warp yarn, which is more twisted in spinning and stronger than weft; fine silk thread used by tailors, hatters, etc. A cord, thread, or the like, formed by twisting, spinning or plaiting.

Long loose overcoat of Irish origin, made of frieze or other heavy overcoating, frequently with a waist-belt.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

Mixed fabric mainly employed for waistcoats, having a wool weft with a warp of silk, silk and cotton, or linen, and usually striped.

Collar, from the name of a Flemish painter A. Van Dyck, who flourished in the first half of the seventeenth century; a large point of some dress-fabric, a row of which forms an edge or border, as is seen in the broad collars or capes of Van Dyck's portraits; a cape or collar with large points.

(Stanford Dictionary of Anglicised Words and Phrases)

A wild ruminant of the Andes.

Short for vicuna cloth, a very soft woolen fabric, usually twilled and napped, made from the wool of the vicuna, or an imitation of it made from fine merino wool.

(Webster's New International Dictionary)

Heavily starched cotton fabric with a plain calendered finish, converted from lightweight sheetings and print cloths and generally dyed black or grey. Uses: interlining men's and boy's clothing to add body to the garment.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Very durable cloth having a linen warp and a woolen weft. Also spelled WINCEY.

Cloth for window blinds. A linen or cotton cloth sometimes glazed, used for clothing, window shades, etc.

Heavy loose woolen material with a nap; coating.

(Shorter Oxford)

Woolen blanket with a dense nap, made in Witney, Oxfordshire, England. Not generic, but could only be applied to the blankets made in Witney. Sometimes called Witney point blankets. A British woolen serge napped on both sides.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)

Square cloth, any cloth with the same number of ends and picks per square inch.

(Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles)