Articles

The Incarnation of Meaning:

Approaching the Material Culture of Religious Traditions

1 The "Spiritual Life — Sacred Ritual" project at the Provincial Museum of Alberta began in earnest in 1976 as a research, documentation, and collections project which could feasibly generate a major permanent gallery by 1979. Those of you familiar with gallery planning throughout museums will realize that the administrative proposal that a particular programme generate a gallery by date "X" is similar to the common, though nontraditional view of God's arbitrary demands upon his lowly creatures, sent into a world in which he does not have to live. So with the Ethno-Cultural programme when, in its infancy and with virtually no collection to draw upon, the edict, "Have a gallery by '1979," was handed down.

2 An underlying issue for virtually all ethno-cultural, ethnic, or folk culture programmes in institutions under direct political jurisdiction is that exhibits treat the cultures of immigrant communities with accustomed political glibness. The recent interest in the "rise of the unmeltable ethnics" and the political profile of ethnic communities has now made significant work possible. Consequently, it is time for researchers, curators, and museum administrators to bring the weight of their respective institutions and the integrity of the intellectual disciplines in which they work to bear on the shape of research programmes and exhibits in this area.

3 Given the material poverty of many local immigrant communities and I must say, the skill of the Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies in skulking off with collections via its annual sorties into Alberta, along with a range of other considerations, I proposed a project which would survey the ritual life current in Alberta, document it, and collect related material culture. The procedure was quite simple, the details complex and often subtle, and the experience extraordinarily rewarding.

THE PLACE OF RELIGION IN THE LIFE OF IMMIGRANT COMMUNITIES

4 In western Canada a central element in the structure and life of virtually every immigrant community is religion. Immigration, the very act of individuals and communities picking up, lock, stock, and barrel, moving to western Canada, and establishing a new life, has, in a number of instances, been directly motivated by religious concerns.

5 The visible examples are the various expressions of the Anabaptist tradition: the Hutterites with the lehrerleut and dariusleut located almost totally in western Canada, and the proliferation of Mennonite expressions which dominate parts of the western Canadian landscape. Whether we look at the Dutch-North German Mennonites who migrated to Canada via Prussia and Russia in a series of waves from the 1890s through the mid 1920s, or at the Swiss-South German Mennonites who came after a sojourn in the United States, we are considering a group of peoples that migrated to ensure the possibility of actualizing their religious faith. Under the historical conditions of southern Russia during this period, it was increasingly difficult to maintain their Germanic cultural enclave and the principles of their faith. The communities from the United States were experiencing pressure resulting from the build-up to the first Great War and left in lieu of persecution.

6 The Doukhobors are a further example. Not only was their initial migration from Russia to Canada largely a response to persecution, but their movement from settlements in Saskatchewan to British Columbia (and for a small segment of the community to the grain belt of Alberta) had a complexity of reasons, not the least being their religious sensibility and belief as incarnated in social structures difficult to marry with those current in Canadian society.

7 During the settlement period there were numerous other examples, perhaps less dramatic, but similarly poignant. German and Swedish communities moved out of Russia along with the Anabaptists. In some cases they came as parishes and, on settling in western Canada, constructed a church and framed the bulk of their social and cultural life around it. The majority of Alberta's German-speaking people did not emigrate because of direct religious persecution but they most assuredly did gather in communities where the church, be it Roman Catholic, Lutheran, or Reformed, was a primary factor in shaping the community's life. The substantial immigration of people who had adopted the pietistic stance that flourished both in the centre and on the margins of the Lutheran church saw the fellowship of the brethren within the church as the centre of life. This included the majority of Norwegians, half of the Danish and Swedish communities, along with a handful of Icelanders and Germans, and of course the followers of the great Count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf, the Moravians. The centrality of church in the life of both Catholic and Orthodox peoples from eastern Europe is obvious. Time in the eastern church is counted from feast to feast through the liturgical year. This flow of the community's life has within it the counterpoint of initiatic acts, whereby the mortal lot of the individual passes through history to the eternal.

8 Certainly the same can be said for the Jewish community of western Canada. Persecution, and the fear of it, were fundamental to the impulse to migrate, whether for the "religious" Jew or for those who followed the Utopian visions of Montifiore or Baron de Hirsch. These two entrepreneurs launched programmes whereby a portion of the world's Jewry could return to an agrarian life, in the hope that this would alleviate the longstanding bondage resulting from their identification with commerce. The synagogue has remained the centre of community life for most Jews, and it is only very recently that any alternative structures are challenging the role it has played since the destruction of the Second Temple and the diaspora.

9 Protestants of a fundamentalist bent coming from the United States had a marked impact on the religious life of western Canada. They established nondenominational churches, Bible schools, and missions. One need only walk into the auditorium complex in the little town of Three Hills, Alberta, and scan the 3,000 seats to realize that such groups had a significant shaping power in the early history of the Bible Belt. Morman populations migrated as parishes to both the southern and northern sections of Alberta.

10 The Japanese population, almost totally Buddhist, received a major boost at the hands of the federal government in 1942. Not only was the community's population on the Prairies raised astronomically overnight, but Buddhist churches were established in largely Mennonite and Morman communities. The Buddhist church, in its function as a social and cultural centre, is a phenomenon unique to the New World. Like churches in general, it takes on inflated proportions when a people are uprooted from their indigenous culture.

11 Among the substantial population of East Indian peoples that have immigrated to western Canada in the last decade, there is a remarkable diversity of cultures and forms of religious devotion. Perhaps the easiest community to speak about is the Sikhs. Alberta has a substantial Sikh population, many having come from Africa via England and some having immigrated directly from Punjab. They were organized as a definite religious movement by the tenth guru, Govind Singh (1675-1708), into a tightly-knit fraternal organization called the Khalsa. It is the Khalsa which gathers regularly for worship around the scripture. Guru Granth Sahib. It is the Khalsa which provides the immigrant with a supportive structure for the spiritual and often the material dimensions of life.

12 The Hindu population is quite a distinct phenomenon as an immigrant group. It shows the diversity that is inherent in Hinduism with its various races, ethnicities, cultures, and religious devotions. The revelations, Shruti and Smriti, along with the epic narratives of the Mahabarata and Ramayana, are common referents, but the various subcultures within the community follow this body of revelation in quite different ways. The complexity is part of the local communities in Edmonton and Calgary; consequently a variety of organizational structures exist. However, the cultures share more referents with each other than with the dominant culture of Alberta, so it is common for them to seek ways to share cultural and religious events. Unquestionably, religious structures provide the main vector whereby they assemble.

13 That religious institutions have been, and for many in western Canada remain, a central social and cultural structure is axiomatic.

SOURCES AND ISSUES IN APPROACHING RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS

14 A good deal is known about the history of religious traditions, their myths, symbols, and theological constructs; historical works on their institutional structures abound. Considerably less, however, is known about religious practice, particularly in the lives of common people. For example, it is far easier to find a good ethnographic study of shamanistic practice among the Osmanli Turks or Savaras in India than it is to find a simple description of liturgical practice among the Lutherans in Norway in the nineteenth century, the immigrant communities who follow the Orthodox tradition, or the brethren who inherited the puritan and reformed movements. Ethnographic descriptions simply do not exist, and social and cultural historians seem to have overlooked religious practice as part of their domain.

15 The initial task in this project was to gather extant research material: the rare ethnography and historical study of religious practice that has been done, manuals of ritual practice including ministerial service books, studies on theology pertaining to ritual practice, and current examples of religious service bulletins. It is important to note, however, that the specific orientation of a given religious community will influence the ritual aids in use. This is particularly true where the tradition is outside a magisterial domain and where the community is just beginning to accommodate itself to North America. I would like to illustrate a sample of issues important in approaching religious traditions as they currently exist on the Prairies.

16 Within magisterial tradition like the Roman Catholic church, ritual practice is prescribed. Provided the parish is not deviating from the revisions outlined by the church fathers at the Second Vatican Council, the liturgical manuals will be standard for the language group involved. This does not for a moment mean that the ritual setting and the form of celebration will be equally as predictable. On the contrary, it is hard to imagine a time in the history of the Roman church since Constantine when there was more flexibility from parish to parish — indeed, even from the celebration of Holy Eucharist at 9:00 a.m. on Sunday and at 10:00 a.m. on the same day in the same parish. The study of religious practice is concerned with the particular in the framework of the general rubrics, but the particular nevertheless.

17 Orthodoxy likewise has its ritual manuals for each patriarchate. Liturgical practice varies little from patriarchate to patriarchate. The grandeur of the Divine Liturgies of St. John Chrysostom, of St. Basil the Great, and of the Pre-Sanctified (or the Liturgy of St. Gregory of Rome) has remained virtually unchanged throughout the centuries. There has been no council of general reform such as the Roman church underwent with Vatican II. Such a council is being called for the early part of the 1980s, however, and the changes it will introduce into this time-honored tradition are difficult to predict.

18 English has been introduced, in part, to the liturgies of the Orthodox church. The translations in use cross the boundaries of patriarchate.

19 Good descriptions of the Divine Liturgy exist, written by specialists from within the tradition. As early as the sixth century we have the beautiful description of the mythic action portrayed by the liturgy in the writings of St. Maximus, the Greek theologian and ascetic writer. A Manual of The Orthodox Church's Divine Services2 with extensive comments by Archpriest Sokolof gives the uninitiated a grasp of the liturgical action as it plays out the Gospel story.

20 Lutheran churches, also within the magisterial tradition, have passed from small ethnic synods through a series of mergers into the large corporate structures, The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Canada and The American Lutheran Church. The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod avoided the mergers of the 1950s far better than it has avoided schisms. Given the recent serious rupture in its congregations and among the intellectual leadership, the future may find it marginalized along with the small splinter groups that broke away from the merging bodies in the 1950s.

21 Lutheran liturgical practice was carried to Canada from the country of emigration and the text was eventually cast in English. This process is exemplified in the Concordia Hymnal (1932), the Lutheran Hymnal (1941), the rather controversial "red hymnal" of 1958 called the Service Book and Hymnal, and the Lutheran Book of Worship published in September 1978 which saw all the synods cooperatively involved. Practice, however, varies depending on the congregation. If the service book is followed closely, one of the three settings provided for celebrating Holy Communion will be used. On some occasions a "folk" modality will be introduced. Here, a guitar accompaniment with the young people of the church involved will include a procession, the wine and homemade bread (whole wheat) for communion carried in a pottery vessel and plate, the Bible, and banners recently made by the parish's budding artists. A processional cross may or may not be present. The service will follow the general rubrics of the service book but do so in the "folk" form. This varies greatly but may go so far as to replace the scripture readings of the day with readings from Kahlil Gibran or some popular verse or song that fits the theme of the celebration. There are a few Lutheran churches, tied closely to ethnic communities, which retain the form of "free church" worship that dominated the Scandinavian synods prior to the mergers of the 1950s.

22 The Mennonites possess several common factors affecting the shape of religious practice within the hundreds of "free" churches that dot the Prairies. Worship in this tradition may appear similar to the uninitiated, but a close examination will usher one into a plethora of subtleties born out of their encounter with the New World. The major organizations, Mennonite Conference, Old Mennonites, and the Mennonite Brethren, have periodically published hymn books along conference lines. Particular congregations use a second book drawn from the pan-fundamentalistic and evangelical experiences of America. The Mennonite Brethren have moved farthest down this path of acculturation, resulting in some congregations dropping the "Mennonite" name and becoming "community" churches. The Conference Mennonites have a substantial percentage of people in urban congregations and therefore are sorting out the implications of moving from a farming-based fellowship to one made up of professionals and businessmen, as well as the ramifications of losing their ethnic base. The Old Mennonites, still largely a rural movement, have been seriously challenged by the portion of their membership successful at developing businesses to service the agricultural industries, and by those who have shifted from family farms to agribusiness. Each requires involvement with organizational and legal structures that their traditional morality and ethics shunned. This has challenged the doctrine of separation from the world, which the tradition has prized since its birth in the fifteenth century. Schisms have occurred as a consequence. Lines are drawn on issues of modernity. Mennonite practices that fell into abeyance are resurrected as a sign of protest and a means of social closure.

23 Further issues can be highlighted by looking at religious settings outside the Christian domain.

24 An Islamic community has existed in Alberta since the early 1920s. The initial immigrants, Lebanese, came to participate in commercial trading and in fur farming. The last decade, however, has witnessed remarkable growth in the emigration of Moslems from the Arab peninsula, Africa, India, and Pakistan. The orthodox Sunni tradition, besides having to work out its identity in the face of the dominant Christian culture, now has its two major rivals from under the canopy of Islam, the Shi'ite and Isma'ilis, in its midst.

25 The refined ritual prayer of Islam with its correlative bodily movements is standard for Moslems, with little variance between the major branches of the faith. The practice is well known and has been discussed at length within the standard references on Islam.

26 Perhaps the greatest challenge facing local Moslems is the practice surrounding the Sacrificial Feast, the holy month of Ramadan, and the rapidly changing role of the community's spiritual leader, the Imam. The ritual slaughter of animals, a central act in the Feast of Sacrifice, has fallen into disuse because of social pressure originating outside the Islamic community. During the Holy Month of Ramadan, the fasting required throughout the daylight hours places considerable stress on faithful Moslems living as far north as Edmonton. Consider for a moment the implications for people working on projects north of Edmonton when Ramadan falls in late July and August. Finally, the Imam's role has expanded from being simply the leader of the community's prayer, as is customary in Islamic countries, to assuming the broader task of ministry common in Christian churches and to administering the cultural programmes that Arab communities are developing for reasons of international politics.

27 The followers of Hinduism come from enclaves throughout Africa, the East and West Indies, and from India itself. Their roots, wherever the vagaries of the last 150 years may have led, are in India, with its ten thousand deities, its numerous spiritual pathways, and its facility in sanctifying space. Alberta is virtually empty of sacred space, at least as it is traditionally discerned. (The exception of course is the civil deity, the liquid black god of the underworld, pumped in a routine, never-ending litany to the refining temples we revere with self-satisfaction.)

28 But what happens when a relatively small group of people of one national identity, but from various cultures with very distinct pathways to the Holy, settles in Calgary or Edmonton? How do they retain the fragile cohesiveness that comes from a shared national origin, nurture the cultural diversity that has existed for many centuries, and accommodate a variety of spiritual pathways as distinct as that of a Shivratri and a Vedantist? The institutional vectors that existed on the subcontinent simply do not exist here. Yet it is here that the need for a binding factor and a common point of identification through institutional structures becomes a life and death issue for the group.

29 The Hindu Society of Calgary was formed in response to this situation. They called the followers of Hinduism, whatever their devotional path, together around Agni, the god traditionally identified with fire. In the Vedic scriptures Agni is talked of as an incarnation of the Eternal and as that particular manifestation which mediates the desires and hopes of mankind to the Eternal. The central ritual, Agnihotra, associated with the god, is well suited to gather together the various devotions operative in the community.

30 The community meets one Sunday each month around a portable dais set up in the parish hall rented from St. Barnabas's Anglican Church. The Havan Kund is prepared and to the chanting of mantras the cotton wick is ignited and the offering of ghee begins. This primal ritual brings together many of the paths of devotion found in the community. Shivratries gather with the following of Vishnu, Rama, Krishna, and Ganesa. Followers of the Arya Samaj movement, avowed monotheists, sit with polytheists. At the conclusion of the Agnihotra, those having a devotion to a god or goddess whose special feast day falls within the current month gather at another altar provided by the Hindu Society. After preparing the idol3 deity and the various aids to devotion, they perform Arti with the general community standing in reverent attention. The service closes with the singing of "The Hymn of Peace."

31 There is considerable literature on Hindu ritual as practised in India. Little, however, exists on what accommodations are made with the transplanting of these practices to Africa, the East or West Indies, or the New World.

32 The service manual produced by the Hindu Society of Calgary is a simple mimeographed booklet,4 a bilingual (transliterated Sanskrit and English) translation of the Sanskrit mantras with brief notes on the rubrics of the ritual. The English literal translation has a serious problem. Each mantra reads as a petitionary prayer to the god Agni, begging for a series of favours to enhance the life of the faithful. Longevity, health, prosperity, and fecundity are chief on the list.

33 For example one mantra reads:

34 The following is a translation of the same mantra done with a working knowledge of Sanskrit and English, and of Vedic and Christian theology:

35 A similar problem faces the translator of the ritual texts of Jodo Shin-shu Buddhism. Translating from classical Chinese, the ritual language of this tradition, into English is difficult at best. Add to this the additional problem of a Buddhist philosophical and psychological framework and the translator's task is taxing indeed.

36 When I first read the English translation of the "Service of Thanksgiving" published by the British Columbia Young Buddhist League,7 it struck me as the work of a Methodist clergyman who had converted to Jodo Shin-shu. I do not mean for a moment to reflect on the inner condition of the translator but only to stress that in English the ritual texts use the conceptual structures of the reformed protestant tradition.

37 This can be illustrated by reflecting on the cast given to the central formulation of Jodo Shin-shu, its central invocation and act of faith. The Nembutsu begins, "I put my faith in Amida Buddha . . . ".8 Buddhism, in virtually all its schools, has focused on the illusory nature of the human ego, of the "I" and "my" in the translated text. I am told that such a formulation simply is not possible in Chinese or Japanese. To say "I put my faith . . . " is simply not an option in the mother language and is a direct contravention of the religious teaching of Buddhism. Yet in Canada we find it in use as the keynote of the tradition. Twice this translation of the Nembutsu focuses on the personal ego as a separate entity exercising Promethean "faith" in the face of the totally "other." Following is a translation that comes considerably closer in maintaining fidelity with the Buddhist tradition: "Amida Buddha's Infinite Grace Source of Faith, Infinite Life and Light."9

38 The Sikh community in western Canada is in a period of marked transition. This has been graphically evident whenever I have had the pleasure of sitting with them. Several have the five "K's" — Kesh (the unshorn hair), Kangha (the comb), Kachha (the knickers), Kirpan (the sword and dagger), Kara (the iron bracelet) — in evidence. They sit alongside fellow members of the Khalsa who wear only the iron bracelet or some combination of the five symbols. Some of the brethren were literalists when it came to interpreting the words of the "living teacher" Guru Granth Sahi V10 and to interpreting matters of tradition. Others had remarkably secular minds on most issues but maintained a constant fidelity to the brotherhood embodied in the Khalsa. Still others were deeply shaped by the mythic structure of Sikh tradition, had grasped its mystical theology, but exhibited none of the outward symbols of the faith. In their interpretation of the meaning of liturgical texts, symbols, and practices, they all spoke to the issues with passion.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF MATERIAL CULTURE IN RELIGIOUS LIFE

39 The religious practice of ordinary people has been largely ignored. This refrain was sounded by the French sociologist Henri Desroche as early as 1968.

40 Likewise the dean of American church historians, Martin E. Marty, in his book A Nation of Behavers,12 calls for a remapping of the religious topography around forms of religious behaviour. Behaviour, practice, the way people incarnate their beliefs and sensibilities, brings us to a consideration of the ritual environment.

41 The material culture of ritual settings not only provides props to worship but also incarnates the myth, giving it flesh and washing the senses with meaning.

42 The "Spiritual Life-Sacred Ritual" project aimed at documenting a selection of ritual practices in situ, acquiring a sample of the material culture of the various settings insofar as the museum could accommodate them and, where acquisition was impossible, photographing them thoroughly, and making a small beginning in the task of exploring the changes that ritual settings have undergone throughout the history of the given tradition in Alberta. Implicit in the latter analytic task is the thesis that an intimate connection exists between the material culture of the ritual space and the mythology it celebrates, and further, that when the material culture changes, it is likely that a change in the myth or at least in the understanding of the myth has taken place.

43 I would like to illustrate this point by drawing on three examples: the changing character and place of altar and tabernacle in Roman Catholic churches; the move toward simplifying the altar shrine in a Jodo Shin-shu Buddhist church; and the place of "regulation dress" in a conservative Mennonite fellowship.

44 Roman Catholicism has long held to a teaching on the "reserved sacrament," that the bread or host, once consecrated as "the body of Christ," is to be handled, used, and stored in a way prescribed by the rubrics of sacramental theology. There is a movement afoot in the church to continue the shift in emphasis that was ushered in with the Second Vatican Council. This shift involved a dramatic change in the arrangement and artifacts in the sanctuary of the church.

45 First, let us look at the altar and tabernacle as it was in the pre-Vatican II church, using the description found in the standard manual of the time used to instruct priests in the arrangement, function, and meaning of the ritual setting. Adrian Fortescue, in The Ceremonies of the Roman Rite Described, says:

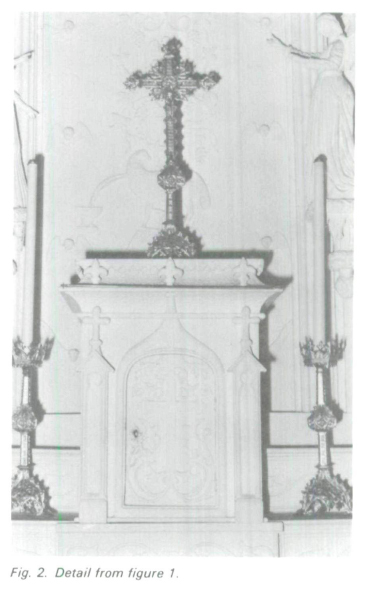

46 The focal point in this setting is on the vertical line from crucifix to tabernacle to altar (fig. 1). The altar developed as a play on the biblical typology of the "altar of sacrifice," stretching in the narratives from Cain and Abel to Isaac, the sacrificial blocks of the Israelites in their desert wandering, and the altars of the First and Second Temples. As an "altar of thanksgiving" it moved from Noah to the passover table at which Jesus of Nazareth instituted Holy Eucharist. The altar is at once womb, tomb, and table. Likewise, the tabernacle follows the biblical narrative of the "tent of the presence" (tabernaculum means tent) which Moses pitched by the Israelite camp: "He called it the Tent of the Presence, and everyone who sought the Lord would go out to the Tent of the Presence outside the camp."14 (I mention the Biblical narratives in order to point out the breadth of meaning invoked by the altar and tabernacle.)

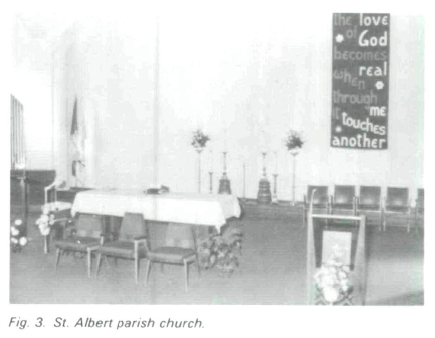

47 The current move within the Roman Catholic church is to shift the emphasis from the altar as womb and tomb to its place as the communion table. The altar is the "Table of the Lord," and, in the words of the Liturgy Commission for the Archdiocese of Edmonton, it "should not be a tomb-like barrier."15 I do not suggest that its role as a place of sacrifice and of the celebration of Christ's sacrifice has been removed from the formal understanding of the church, but only that the weight of emphasis has shifted. The current recommendations are to build a permanent structure, solid in construction, preferably square and unimposing. It is drawn out from the wall and is as close to being in the midst of the congregation as possible. The celebrant now faces the congregation during the Eucharistie Prayer, and all the actions at the altar are done for the congregation to see and participate in. The top of it should be free from clutter so that the bread and wine to be consecrated are clearly visible. The focal point is the "Table of the Lord" (fig. 3), around which the community can gather to receive the divine gifts through which salvation comes.

48 The tabernacle has been removed completely from the altar. The Liturgy Commission is revealing on this point.

49 With the rearranging of altar and tabernacle, a shift has occurred in a primary referent, a primary embodiment of the Christian myth. Where the ritual space once ran vertically from crucifix to tabernacle to altar, from crucifixion and death through "presence" to communion, it now focuses primarily on altar as sacrament. The "Table of the Lord" with its corollary human experience, the communing assembly, is the focus of the human spirit. The vertical matrix of crucifixion and death, through "presence" to communion, is downplayed.

50 The possibilities of mythic identification with the ritual setting have changed. On the surface they would seem to have shrunk. But have they? The question remains.

51 Another example, drawn from the Buddhist churches of southern Alberta, will illustrate the issue of mythic identification further.

52 Jodo Shin-shu ("True Pure Land School") is a form of Buddhism said to have been founded by Shinran (1173-1262). Orphaned as a child, he set out in search of understanding, peace, and enlightenment following a time-honoured path. He entered the Tendai monastery on Mount Hiei and studied with the great teacher Honen (1133-1212). Honen taught him to place his religious commitment in the recitation of the Buddha's name as found in the formula called the Nembutsu. Through this practice, reciting the formula Na-Mu-A-Mi-Da-Butsu continuously, merits were accumulated and upon death the devotee would be reborn into the pure land, enlightened. The theological and spiritual issues are beyond our purview. Suffice it to say that Shinran, after considerable struggle, began to teach that the Nembutsu was rather an expression of gratitude, thanksgiving for having been born into life.

53 With this "theology" in hand we enter the Buddhist churches in Alberta with a view to seeing how it is acted out, how it is celebrated, cultivated, and embodied.

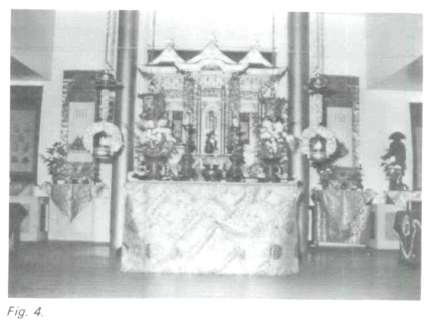

54 The image of Amida Buddha may be in the form of a statue, a scroll with a depiction on it, or a scroll with the six characters Na-Mu-A-Mi-Da-Butsu, which invoke his name. The altar (fig. 4) is decorated in gold leaf on black lacquer, with fresh flowers, candles, incense, gongs, bells, and food on it. All the senses are appealed to through transient forms of life. The Buddhist message, its gospel, is vividly portrayed: "All is transient, all fades and dies. There is nothing permanent, nothing graspable, nothing secure." The scroll of Honen, Shinran's teacher, and of Prince Shotoku, the founder of Buddhism in Japan, make the necessary historical connections (fig. 5). The Seven Patriarchs lead in direct succession to Jodo Shin-shu. The eighth Abbott of the movement, named Ren Nyo, is also present (fig. 6). In several churches a scroll called the Niga Byakudo, or "The Two Rivers and The White Path," is found. It graphically depicts the struggle of man with his passions and the enticing whims of the world.

55 The historical and mythological referent found in the original Buddhist church at Raymond, Lethbridge (north church), Coaldale and Rosmary are distinct from what we see in the Lethbridge Honpa Church, established only fifteen years ago. Here a simple altar (fig. 7) with the Amida Buddha's image is graced with flowers, food, candles, and incense. However, the scrolls carrying the historical and mythological story are absent.

56 The Seven Patriarchs, Prince Shotoku, and Honen, through whom the Buddha-darma passed to Shinran, are notably absent. The Eighth Abbott of Jodo Shin-shu, a key figure in the transmission of the teaching to contemporary devotees, finds no place of remembrance in the area surrounding the shrine. Shinran himself, either as pilgram or venerable teacher and saint, is without representation. The central image of the enlightened Amida Buddha, alone, remains.18

57 Perhaps what we are beginning to see is the church's movement away from the embodiment of the faith in historical and mythological forms identified with Japan. An ideological/theological base that accents the central principles of the faith embodied in the Amida Buddha is replacing the broad imaginative playground visible in the elaborate setting illustrated by the example of the Raymond Buddhist church.

58 The history of Mennonite attire has been sketched out in several places. From the material history viewpoint Gingerich's book, published by the Pennsylvania German Society, is most definitive.19 The Mennonites have, as a cardinal part of their religious practice, called for simplicity of dress. This harks back to the injunction of Saint Paul in the letter to the Romans: "and be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your minds, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect will of God."20

59 While the Mennonites were a rural people, this did not mean more than utilizing the common simple clothing of the indigenous culture. With urbanization and the acceptance of the media of the "world" into their homes, alternative dress became an issue. The situation in Alberta's various Mennonite communities illustrates the general situation.

60 During a field trip in 1976 to a district in southeastern Alberta, I was introduced by my informant and guide to three major movements that account for the majority of Alberta's Mennonite population: Conference Mennonites, the Old Mennonites, and the Mennonite Brethren. Living adjacent to each other in one of the irrigation districts close to Brooks, they have all thrived in the last two decades. During two days of interviewing I saw only two examples of "regulation attire" and these were in the homes of elderly couples in the Old Mennonite tradition. The Conference people dropped standards of dress while still in Russia. The Old Mennonites, inheritors of the Dutch-North German strain of the faith, maintained standards of dress till the mid 1950s. The Brethren people, while still in Russia, viewed the standard dress forms as an external sign that had often become a substitute for the "inner" religious experience of conversion. Consequently, they have tended to question its use and very early in their history dropped any formal concerns about it.

61 During one interview, in the home of a minister of the Old Mennonite church, talk about changes in church discipline opened up the history of a schism in the community that occurred in 1965. From his viewpoint, the schism resulted from the Old Mennonites loosening their prescriptions on regulation dress.

62 Driving to the farm of a member of the Conservative Fellowship, the group born out of the schism, we passed a young woman wearing the simple cape dress and bonnet that for the last 100 years has fulfilled the ordinance to be "adorned in modest apparel." For centuries Anabaptists have quoted 1 Corinthians to support the ordinance requiring "devotional head covering" or "headship veiling" worn by women in the fellowship. The scripture passage is delightfully ironic on this, at least when taken in conjunction with the Mennonite practice.

63 The rather fair young woman walking down the country road had her hair tightly braided into the standard bun, firmly and neatly pinned in place, and covered with the "headship veiling." Alas for the long hair that was her glory!

65 The Conservative Mennonite Fellowship is part of a widespread phenomenon affecting virtually every wing of the Anabaptist movement. It marks a new chapter in the history of the tradition. There is a strong element of retrenchment in its attempt to institute ordinances and ritual elements of the tradition in order to bring about social closure and generate a viable spiritual community.

65 Adopting "regulation dress" and similarity in living accommodations and lifestyle is a serious attempt to live out the Anabaptist vision in the face of modernity. A new play on old religious forms is in progress. A thorough study of the material culture, its function internally for the particular church and externally as a means of relating to the "world," would assist greatly in our understanding of this attempt to live counter to the dominant culture.

66 A further element I would like to touch on briefly is what might be termed the strictly folk elements of religious practice. Formal liturgies prescribe the use of artifacts and gestures in detail. Folk traditions, however, continue to appear within ritual settings. Take the case of the Coffee Crisp chocolate bar. The ritual of Prohod in the Romanian Orthodox community is a feast occurring after Easter and before Ascension in the liturgical calendar. It consists of reading the names of the deceased from the church Pomelnic into the "Litany for the Dead" and of the priestly blessing of the graves of all the faithful buried in the church cemetery. The departed servants of God are remembered to the Lord and Saviour. The material culture of this setting is a linen cloth laid out on the grave of the most recently departed relative (linen is always associated with the swaddling and burial cloths of Jesus); a white candle of beeswax, symbol of the "Light that came into the world to vanquish all darkness"; grapes or wine, calling to mind the saving blood of Christ; and bread, likewise to become the body of the Lord, broken, dead, buried, and resurrected for our salvation. But what of the little oddities found in the baskets on the graves — the Coffee Crisp chocolate bars, cookies, spirits, sweets of all sorts? Priests have told me that these items do not belong, but they add, "You know how people are." The people have explained that a favoured food of the departed is placed in the basket with the symbolic items and, after the blessing, it is consumed by the children during the feast over the grave.

67 There are numerous examples of such anarchic elements within liturgical settings. Given the militancy of religious leaders in purging the strictly ethnic and folk elements of faith, there is a great need to document their place and function within worshiping communities.

68 The material culture of religious traditions is rapidly changing. I am convinced that solid studies in the area will help us understand how human communities discern and celebrate the meaning of life. Ritual artifacts are changed with the myth of the religious tradition certainly as much as the theology. S.G.F. Brandon, writing just before his death, put the issue this way:

*The author wishes to thank the Provincial Museum of Alberta for the opportunity to carry out this research project and also David Richeson, currently of the National Museum of Man and formerly Head Curator of Human History at the PMA, for his encouragement and suggestions in the formative stages of the project.