Articles

A Review of Clayburn Manufacturing and Products, 1905 to 1918

En 1909, la Clayburn Company Limited est devenue la plus grosse briqueterie de Colombie Britannique. Fondée en 1905 sous le nom de Vancouver Fireclay Company, la Clayburn a fabriqué une grande variété de briques et de différents autres produits en argile très répandus en Colombie Britannique, particulièrement dans la région de Vancouver, et même sur les marchés extérieurs. Le succès de la Clayburn peut être directement attribué à la richesse de l'argile et aux dépôts d'argile schisteuse que l'on trouve sur la Sumas, montagne située à environ quarante milles à l'est de Vancouver, et qui constitue la meilleure des rares réserves d'argile de la province. A partir de ces matières premières, la Clayburn a produit une brique réfractaire jaune clair et une brique de parement dont l'excellente qualité lui a valu une grande renommée. La compagnie fabriquait aussi des briques ordinaires, carrées ou diversement arquées, des blocs pour les hauts fourneaux des cimenteries et des fonderies, des briques pressées de couleurs variées, des tuiles et des tuyaux d'écoulement. La présente étude porte sur l'expansion de l'usine Clayburn de 1905 à 1918 et sur certains des produits qui en sont sortis.

1 In British Columbia the name Clayburn has dominated the brick industry for over half a century. In 1905 John Charles MacClure founded the Vancouver Fireclay Company Ltd. and established a brickworks in the newly created village of Clayburn, forty miles east of Vancouver. By 1909, when the firm's name was changed to that of the village (which had also been adopted as the brand name of one of the firm's major lines of brick), the Clayburn Company had surpassed in output its largest competitor in the province, the Columbia Clay Company of Anvil Island. After a period of expansion Clayburn purchased its nearby rival, Kilgard Fireclay Company, in 1918. Dual operations continued at both the Clayburn plant, which specialized in brick, and the Kilgard plant, which specialized in clay tiles and pipe, until 1930 when the plant at Clayburn was abandoned and that at Kilgard enlarged to accommodate brick manufacturing as well. The main reason for this consolidation was the economy of transporting clay to the Kilgard site. In 1949 a fire destroyed much of the facilities at Kilgard. Subsequently, part of the operation was rebuilt at Kilgard while part was re-located to Abbotsford, five miles away.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 In 1979, after several name changes, these two plants survive. Flex-Lox operates at Kilgard; Canadian Refractories Ltd. operates at Abbotsford and still uses the name Clayburn on some of its brick products. The Abbotsford plant of Canadian Refractories is the only surviving brick producer in British Columbia in 1979 out of the more than 100 brickyards known to have existed in the province during the period from 1852 onwards. The initial rapid growth of the Clayburn Company and its eventual size and longevity can be attributed directly to the wealth of easily accessible, top quality clay deposits at its disposal from the beginning. This study will focus on the company's development, its products, and its history prior to 1918, before the merger with the Kilgard Company.

3 The variety of Clayburn's clay resources is shown by the different beds of clay on the western flank of Sumas Mountain which is near the settlement of Straiton and directly east of Clayburn village. These beds had been located and named by the company as early as 1909 and were described in the 1908 Report of the British Columbia Minister of Mines as follows:

Although other beds were located later to augment these seven on the western side of Sumas Mountain and still others were located above Kilgard, this early list demonstrates how rich in clay resources the Clayburn Company was, even in its earliest period.

4 Beds one through four, of Cretaceous origin and part of the coal-bearing deposits of that age, were similar to those present in several other coastal localities such as Comox and Extension on Vancouver Island where coal mines had been operating since the nineteenth century. Clays of the type extracted there are generally used for making pottery, firebrick, and other products with a high fusion point.

5 The principal fire clay beds for the plant at Clayburn were located from 2 to 3½ miles east of Clayburn. They were connected to the plant by means of a narrow gauge railway which had a downgrade of about 3 percent to the works. These deposits were generally deep and were accessible only by means of underground mining.

6 Beds five through seven consisted of blue grey silt clays of the glacial period and were useful for the manufacture of common brick. They resembled the many other deposits in western British Columbia from which common or red brick was made,2 including New Westminster, other Fraser Valley localities such as Port Haney and Ruskin, and Victoria. The blue grey glacial clay deposits on Sumas Mountain were located about 1,000 feet east of the brick works and were excavated by means of a steam shovel in an open pit operation.3

Display large image of Figure 2

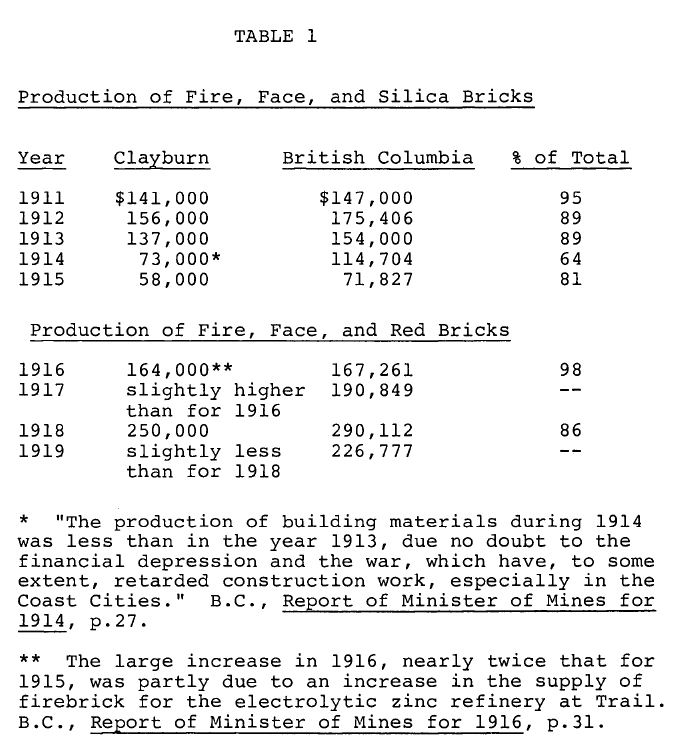

Display large image of Figure 27 The Clayburn Company's early growth is illustrated by the annual Reports of the British Columbia Minister of Mines for the years 1911-19. These reports list the total production by district of miscellaneous building materials and include specific listings for pottery and red, fire, face, and silica brick. In addition to these totals, the Clayburn Company's production was usually listed separately. Table 1 is a composite table giving the total values of production of Clayburn common red and fire-brick compared to the provincial totals for the same products in each year.

8 Much of the Clayburn Company's popularity was probably due to the diversity of its products. An entry which Clayburn submitted to Might's Directory in 1913 indicated that the company manufactured firebrick, square and all standard arch shapes, smelter and cement kiln special blocks, sacked ground fire clay, pressed brick in buff, grey, speckled, red, and full flashed shades, agricultural tile, partition tile, vitrified sewer pipe, and common brick.4

9 But diversity was not the only selling point of Clayburn's products; uniqueness must also be considered. For example, Clayburn was the only brick supplier on the British Columbia coast that produced buff-coloured bricks5 or that regularly made specialty bricks. Furthermore, after 1906 Clayburn was the sole manufacturer of firebrick in British Columbia.6

10 For special fire clay shapes or tile, J.B. Millar, plant manager, advised one enquirer that the company could manufacture "anything required" and deliver it within thirty days. Prices for these materials ran from twelve to twenty-two dollars per thousand according to size and difficulty of manufacture.7 One such special fire clay shape was retort blocks, for which Clayburn developed a small market among such local gasworks as those in Vancouver and New Westminster. This work was done by an employee who had formerly worked for the Glenboig Company in Scotland.8 Such was his skill that Clayburn boasted that it could assure better quality and cheaper prices than imported retorts.9 Other specialty jobs included making special stove brick for the Canadian Lang Stove Company Ltd. of Vancouver in 1912, firebricks for the dredge King Edward in 1911, and fire-bricks for Canadian Pacific oil-burning locomotives in 1913 at fifty dollars per thousand.10 The company even supplied clay for modelling on at least one occasion and some employees used it themselves for modelling and pottery work.11 The company also tested the quality of clays sent to it for the purpose from as far away as Winnipeg.12

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

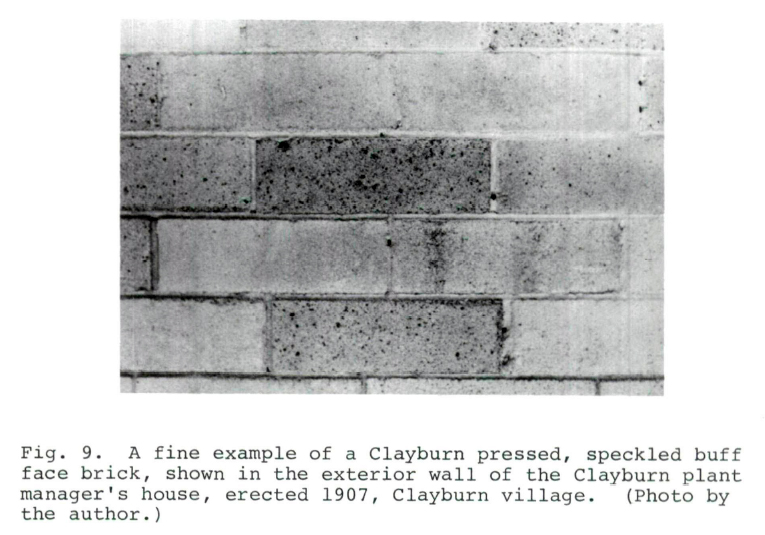

Display large image of Figure 411 Because of the scope of Clayburn's products they were sought after by architects and contractors who wished to add originality and quality to the colour, texture, and design of their structures. The popularity of Clayburn bricks is attested to by their use in some of the most prestigious buildings built in Vancouver and Victoria before the First World War. Among those built in or near Vancouver were the World Building, Dawson Building, and Bank of Commerce Building, all in 1911, the Asylum at New Westminster in the same year, and the Hotel Vancouver, Police Station, and Oakalla Prison Farm in 1913. In Victoria the list includes the Union Club and Victoria High School, 1912, the Royal Jubilee Hospital and Provincial Jail, 1913, and the Armories, 1914. During the 1920s Vancouver's Marine Building and St. Paul's Hospital and the new wing of Victoria's Empress Hotel were three of the most important buildings which used Clayburn bricks in their construction.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 512 The best-known specialty building brick produced by Clayburn was that made for the Hotel Vancouver13 and aptly called "Hotel Vancouver brick." These bricks were a repressed firebrick made for facing purposes and contained a mixture of twenty-two percent Thornton clay and a balance of fire clay.14 They were generally considered by the company to be a very durable product. In fact, when the plant at Kilgard burned in 1949, the company bought back quantities of its brick from the demolished Hotel Vancouver, cleaned them, and used them in the reconstruction of its new plant. Apart from the regular Hotel Vancouver brick the company also produced at least two special bricks for the hotel, one designed especially for two niches in the hotel, the other a larger, moulded brick.15 So popular did Hotel Vancouver brick prove to be that the company marketed it under that name.16

13 Notable among the other bricks specially manufactured by Clayburn were Union Club bricks made for the prestigious Union Club's new building in Victoria. These were a hand-selected, dark pressed brick.17 The fact that the Clayburn Company could obtain an order for bricks in Victoria for any job, but especially for a prominent building such as the Union Club, demonstrates that the company could successfully compete with the local Victoria brickyards in their own market area. This was probably largely due to the company's willingness to make up special orders. But at least one major Victoria building contractor, Luney, was known to favour Clayburn common red bricks even though that was the type of brick the Victoria yards themselves produced almost exclusively.18 Perhaps the company's ability to keep the cost of its products low was another major reason for their acceptance in Victoria. Even after the freight charge of five dollars per thousand and the distributor's ten percent commission were added to the thirty-five dollars per thousand charged for the bricks, Millar could observe that:

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 614 One brick product which can be classified as special but which is, in effect, a natural product of improper burning, is clinker brick. This is brick which has been overheated, has started to melt, and is frequently darker than normal or has a glassy or bubbled surface. In 1914 the company was anxious to clean up its yard and dispose of the clinker brick which it had accumulated. In June of that year it received a substantial clinker order from Victoria at a price of four dollars per thousand.20 Clinkers were used for decorative purposes in residential construction, particularly in the California bungalows popular in Victoria and Vancouver before 1925. This created an additional market for all brickyards on the West Coast, a situation which Clayburn was ready to exploit in a major way.

15 Early brick production at Clayburn initially used the clays first discovered by Charlie MacClure and his exploring partner, Rube Thornton. But these clay deposits eventually were mined out and other sources of clay on Sumas Mountain were brought into use. An exact analysis of the clays used in manufacturing Clayburn brick is not possible. Not only did variation occur between the clays of one mine and another, but also between clays within one mine itself. In the fire clay mines, for example, three layers of clay were laid one atop the other, each separated by a seam of soft coal. The clay of the top layer was the least refractory and that of the bottom layer the most refractory so that in order to insure some uniformity of production the clays of each layer were combined.21

16 Other properties such as weight, colour, and size of the bricks are more easily tabulated than clay composition, although even these properties are not necessarily uniform over time. For instance, the weight of a brick is contingent upon several factors, such as the type of clay used, markings, type of manufacture, and the amount of moisture contained in the brick at the time of weighing.

17 In May 1913 the Clayburn Company quoted the following weights to the British Columbia Electric Railway Company for three types of bricks :

In October 1912, however, a common brick had been quoted as weighing only 4 pounds 7 ounces,23 somewhat less than the 4 5/8 pounds later quoted to the Electric Railway Company. Presumably both weights were for finished dry bricks.

18 Although the Clayburn Company made red common bricks, buff bricks became its trademark. Because of the soft mud24 technique used in manufacturing red common bricks at Clayburn these bricks were all made with a frog, or indentation, on the top. The buff bricks, generally harder and more refractory than the reds, were manufactured by a different process, usually stiff mud or repress,25 and as a result did not bear a frog but had the name "Clayburn" impressed in capital letters on the face of each one.26

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 719 The quality of bricks can also be affected by the burning process. The type of brick being burned determines the type of fuel needed. At Clayburn common bricks could sometimes be successfully burned in scove kilns27 using slabwood, a waste product of sawmills, but higher grades of brick required coal. Size, hardness, and purity were important features of coal which could vary according to the work they were needed for. Before 1914 Clayburn experienced repeated difficulty in obtaining the coal it desired. As a result it tried a number of suppliers, all of whom had difficulty maintaining good quality shipments. Occasional bad shipments of coal, however, did not adversely affect the quality of Clayburn bricks in the long run.

20 Probably because of its wealth of clay deposits and its start in the early twentieth century (relatively late in comparison to most of its competitors in British Columbia),28 the Clayburn Company did not follow the general pattern of development which the older brickyards in the province had experienced. For example, the nearest competitive yards, those at Port Haney (established in 1886), had originally been seasonal operations only, as had been the earliest yards in Victoria. Also, in these other yards the methods of obtaining clay, transporting it to the works, working it, and even drying and burning it had tended to be done by hand or with the aid of horsepower.

21 But the Clayburn Company and its predecessor by-passed these more primitive, unmechanized stages entirely and from the beginning produced bricks all year round, using the most advanced machinery available. By August 1906, after only one year's operation, the vice-president of the Vancouver Fireclay Company boasted that "our plant is modern in all respects " and listed the installations as consisting of:

two dry presses, capacity each 10,000 [bricks]

one pug mill

one auger machine

one repress

one automatic cutter

one eight-tunnel dryer, 105 feet long with force and exhaust fans.29

Although no permanent kilns had been built as yet, the company was burning its first output in primitive scove kilns only in order to make bricks to build for more permanent works.30 In 1909, prior to the re-organization of the Vancouver Fireclay Company, one more dry pan31 was added to the plant, doubling the dry pan capacity of 1906. Also by 1909 seven beehive kilns were in operation, each holding from 40,000 to 75,000 bricks, as well as one Millar down-draft kiln holding 180,000 fire-bricks.32

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 822 From 1909 to 1918 the expansion at Clayburn was supervised by John Brown Millar, formerly a manager at the Don Valley Brick Works in Toronto. Pre-war additions included the extension of the existing plant as well as the addition of new facilities to expand the range of the company's product. In 1910, for example, two new large kilns, each with a capacity of 200,000 bricks, were completed in addition to new dryer tunnels; these were necessary because the company was also installing new pressed brick machinery.33 Also within a year it had finished a completely new plant for producing sewer pipe up to twelve inches in diameter because its clay deposits had been proved "equal to the best foreign and domestic clays for this purpose."34 By April 1911 Clayburn had added a new soft mud plant for common brick with a capacity of 50,000 bricks per day. To serve this plant a continuous kiln was completed by the end of 1911 and the company boasted that it probably had the largest capacity of any in the Dominion.35

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 923 The bountiful natural resources at the disposal of the Clayburn Company, combined with the keen business acumen that inspired the managers to keep up-to-date with equipment and methods, and above all the wide variety of clay products it produced, put the firm ahead of all its competitors. Clayburn bricks have left a visible legacy throughout the province but especially in the Vancouver area where the distinctive buff colour is seen in many firehalls, commercial and institutional buildings, and South Vancouver schools. Clayburn products, especially refractory bricks, have been less visible but of great importance in the industrial life of the province; few bricks taken from post-1905 chimneys, ovens, or kilns, bear any other markings than "Clayburn."

* The research for this article was done in part by the author for his Master of Museology thesis. He wishes to acknowledge in particular Canadian Refractories for the loan of the Clayburn Letterbooks and the many former employees of Clayburn and residents of Clayburn village for their useful information and assistance.