Articles

Art Glass Window Design in Vancouver:

The Role of the Pattern Book

Au cours des trente premières années du XXe siècle, les verreries de Vancouver et leurs artisans se sont inspirés des catalogues américains et anglais pour concevoir et produire des vitraux de maisons. Il semble que les artisans n'aient pas copié servilement les motifs, mais on trouve d'étonnantes similitudes entre les motifs des catalogues et les vitraux encore existants. L'analyse de l'origine des catalogues, dont bon nombre portent l'estampille d'entreprises locales, et une enquête auprès des ouvriers qui travaillaient pour certaines d'entre elles vers 1914 confirment d'ailleurs cette assertion. Les catalogues, utilisés à Vancouver par des artisans de formation anglaise et canadienne, montrent une grande quantité de motifs importés, destinés à un type de décoration architecturale très prisé dans l'est du Canada, aux Etats-Unis et en Grande-Bretagne.

1 Research to discover the origins of art glass window designs used in Vancouver homes and apartments built between 1890 and 1940 has brought to light a number of American, British, and Canadian pattern books which were used by individual craftsmen as well as by firms producing art glass. This paper will provide a preliminary assessment of the significance of these books in terms of production, merchandizing, and artistic influences.

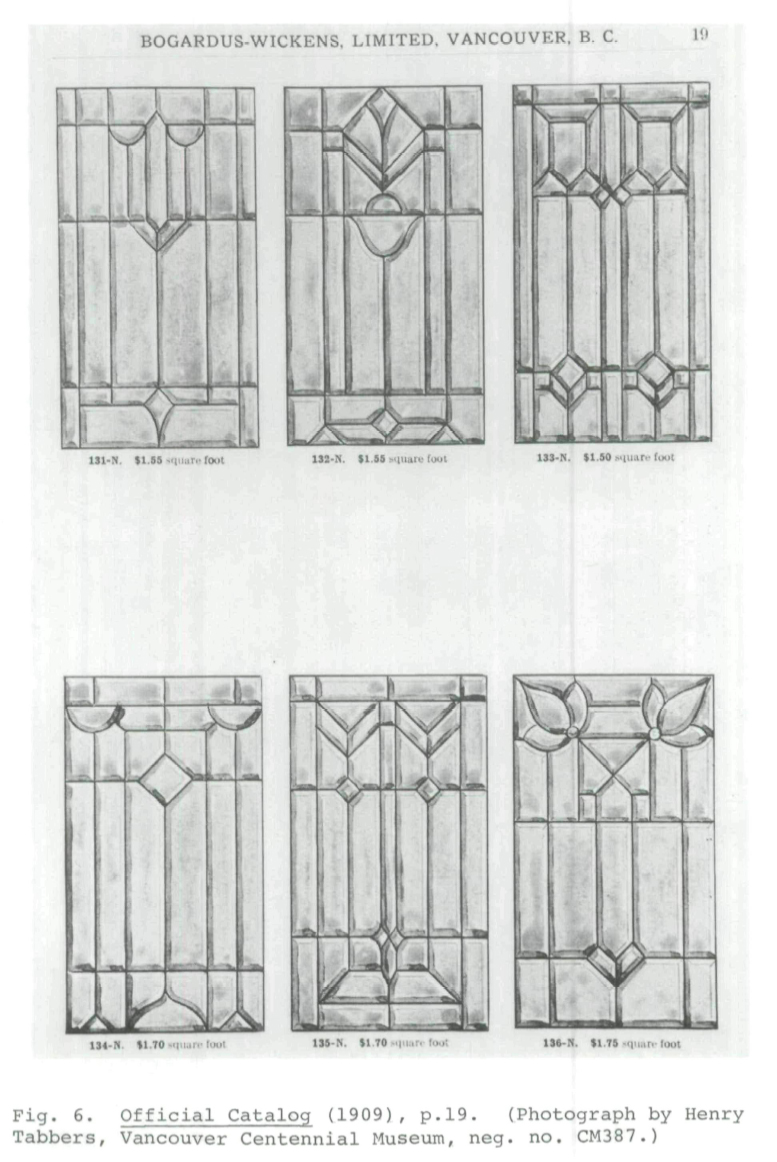

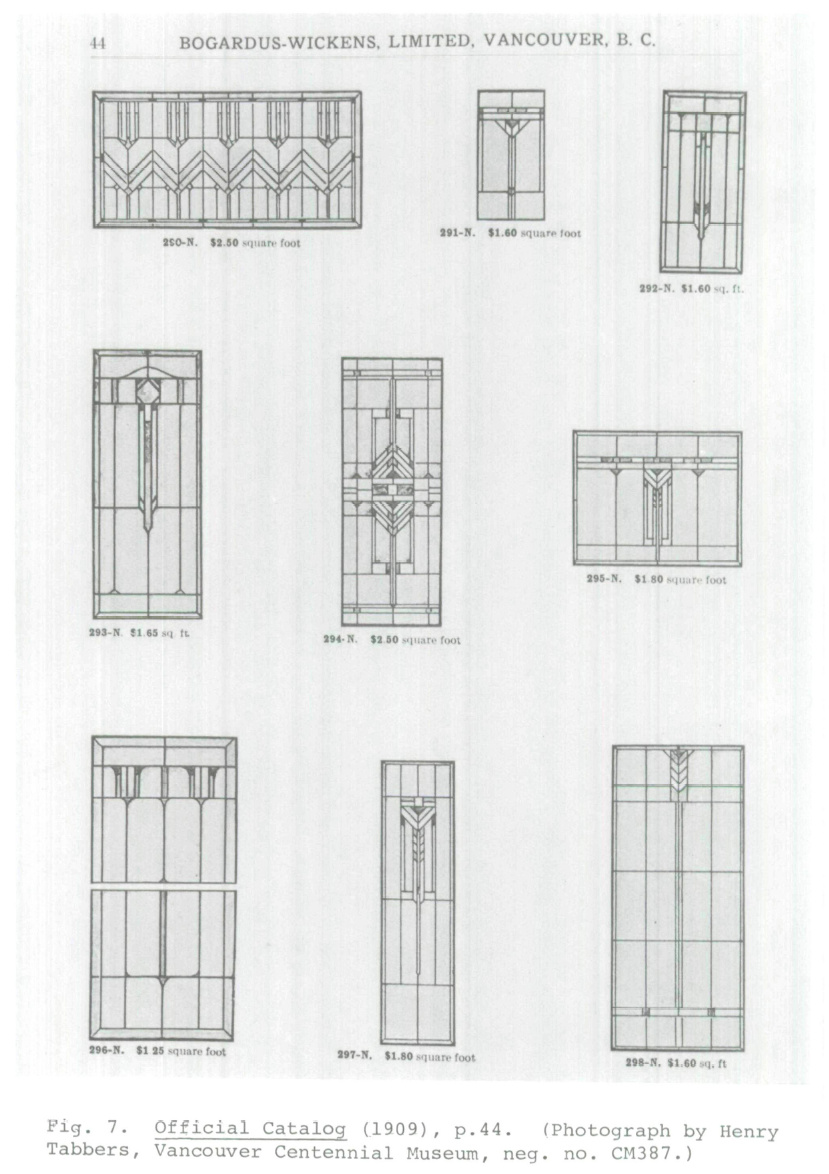

2 To date eight pattern books have been located. The most numerous are versions of an American publication issued in 1909 and subsequently revised and reissued intermittently until the late 1920s. The volume was first known as the Official Catalog (sic) of the National Ornamental Glass Manufacturers Association, a trade organization founded in either 1899 or 1900 at Indianapolis.1 While the Association's membership was largely American a number of Canadian firms did belong and by 1912 the Association had added the phrase "of the United States and Canada" to its name. At the annual meeting of the Association in February 1909

3 Meeting in Chicago on 22-24 March 1909, the Association's executive committee reviewed between three and four thousand designs from across the United States. It chose designs for sixteen pages of clear work, sixteen pages of bevelled plate, and thirty-two pages of coloured work "representing a selection from various parts of the United States,"3 chose a printer, and set prices. The size of the run enabled the Association to offer members overprinting on the cover and on each page plus a fly page for "individuality." Price to members was 25c a copy in lots of 500, 37.5c a copy to non-members. Each purchaser's catalogue was copyrighted and given a special number, the number being the exclusive property of that purchaser. A report in the November 1909 issue of the Bulletin noted that 20,500 copies of the catalogue had been mailed out in the previous week to thirty members.

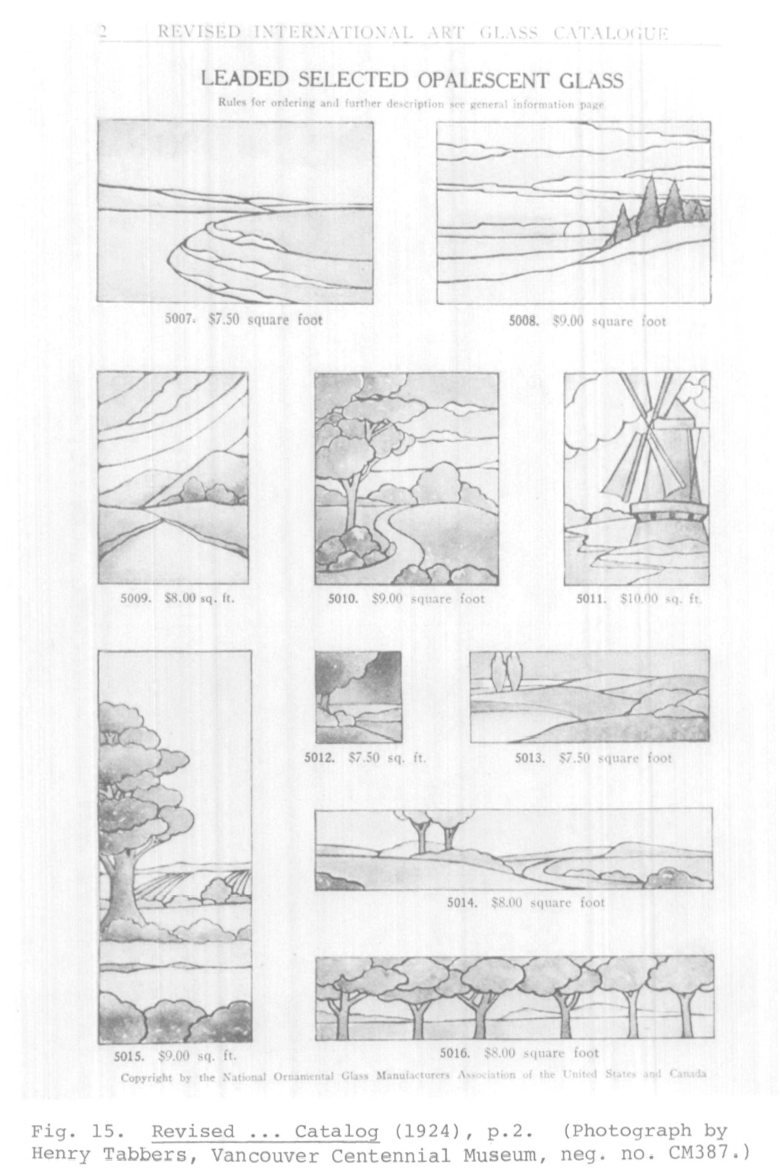

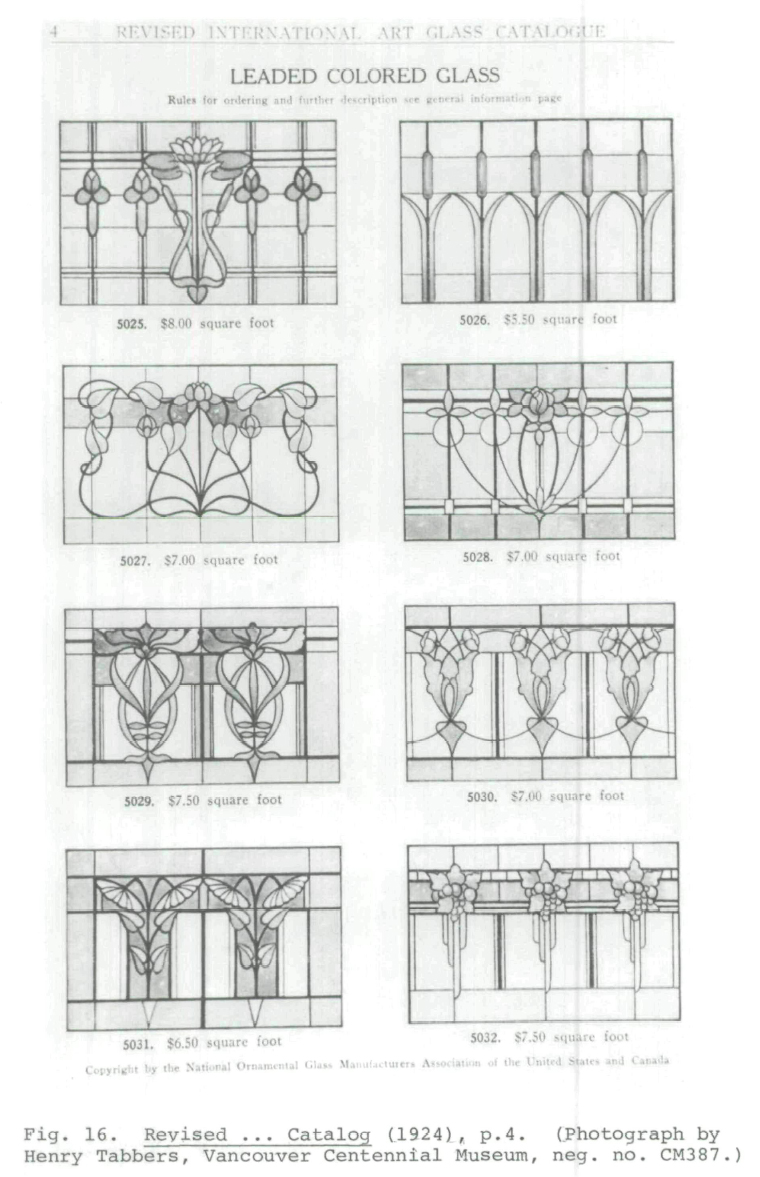

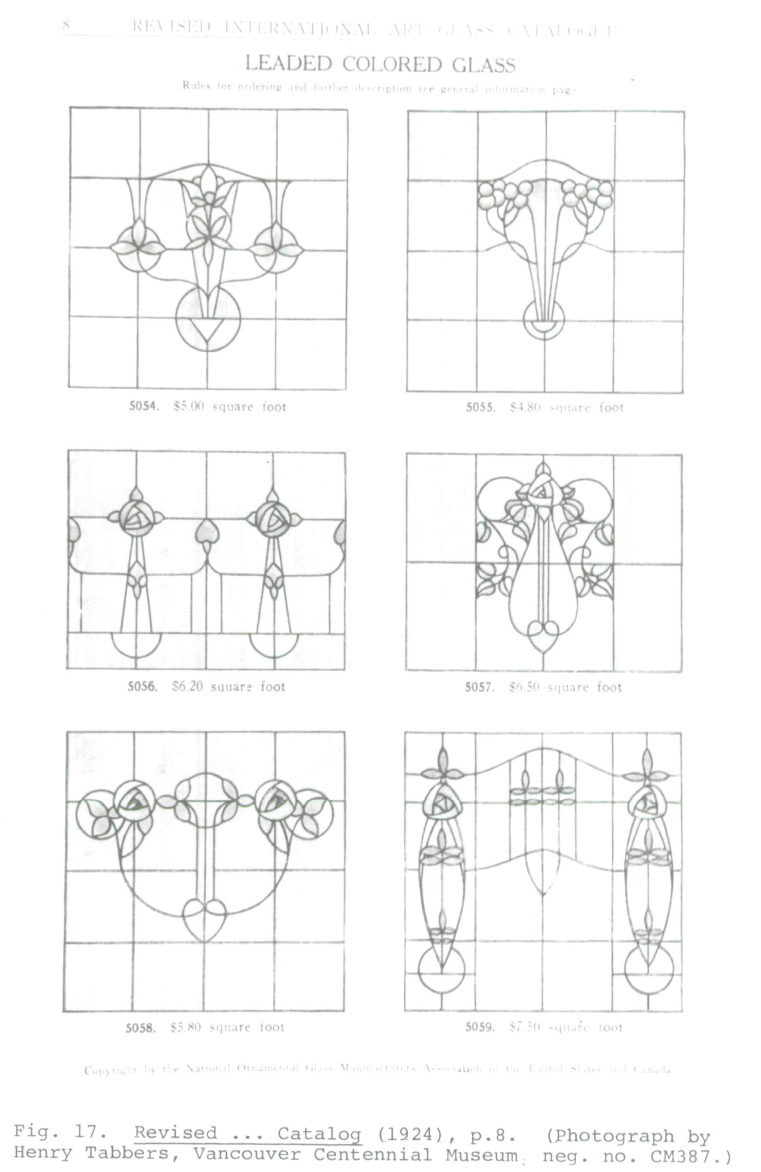

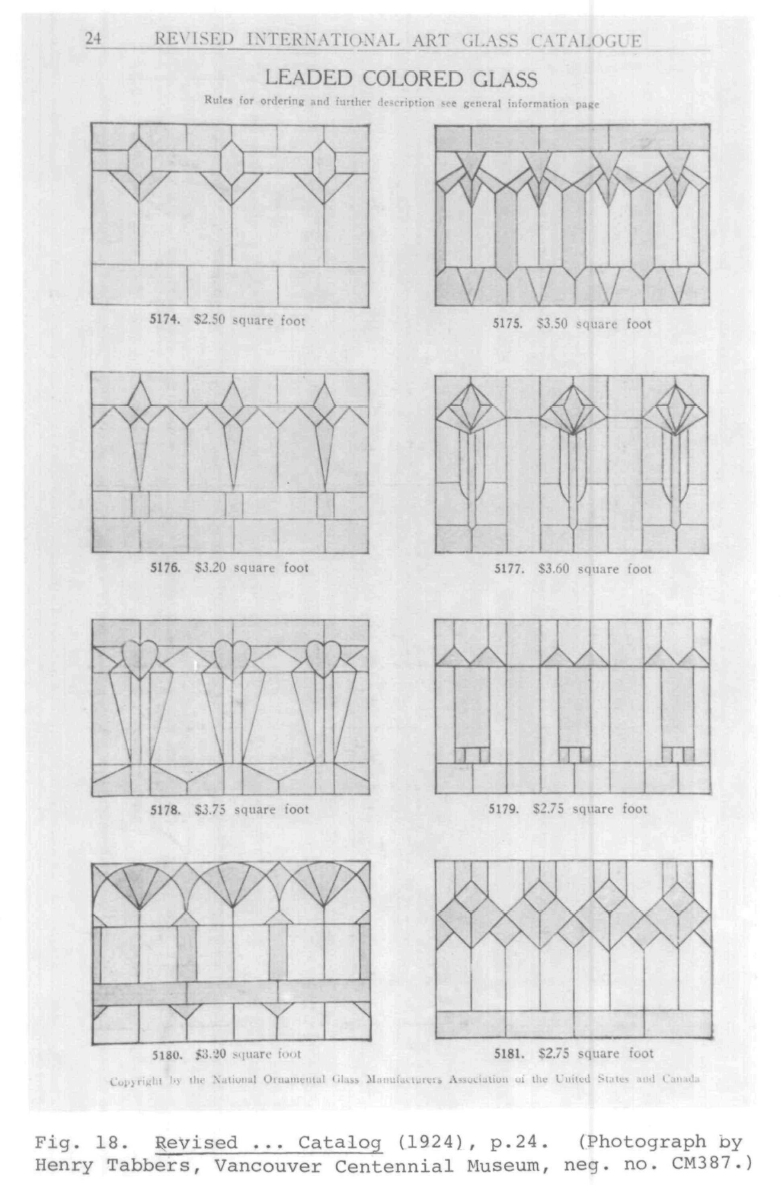

4 A 1913 revision reduced the number of coloured domestic patterns and added seven pages of coloured church designs. Costs of each copy were slightly higher; prices were the same for members and non-members and individual copies could be purchased for $2.00. In 1919 new prices for the catalogue were adopted. More extensive changes were made in 1923 and 1924 when the catalogue was split into a domestic book of 48 pages, Revised International Art Glass Catalog — Domestic, and a 16-page catalogue of designs for church windows.4

5 Of the five copies of the Association's catalogues with a Vancouver provenance, three are examples of the 1909 version and two of the 1924 Domestic version. Two copies of the 1909 edition are overprinted with the names of two Vancouver art glass companies — Bogardus Wickens Limited and Modern Leaded Glass Company.5 The Bogardus company was founded on 1 December 1903 as the British Columbia Plate Glass and Importing Company and on 18 January 1910 became Bogardus-Wickens-Begg Limited. The driving force behind the concern was Arthur P. Bogardus, a native of St. Catharines, Ontario, who recognized the commercial possibilities of art glass and made the company one of the most active art glass merchandizers in British Columbia. The firm eventually became known as Bogardus-Wilson and as a subsidiary of Libby Owens is still in the glass business at the time of writing.

6 Much less is known about the Modern Leaded Glass Company which was in existence for a brief period from 1909 to 1912. Indications are that it was a partnership of Walter W. Roberts, a glasscutter employed at the B.C. Plate company in 1907-08, and John J. Parlett, an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects, formerly a draughtsman with the Vancouver firm of Hooper and Watkins. The partnership lasted only until 1910. Roberts was then on his own until 1913 when he changed the name to Modern Glass Company.6

7 It is worth noting, as far as this study is concerned, that whereas the large Vancouver glass firms such as Bogardus, which appear to have successfully weathered the various economic storms generated by the First World War, the postwar depression, and the catastrophic 1930s, did not depend for their principal support on the manufacture of art glass windows. They also worked with plate glass, auto glass, and mirrored glass — in Bogardus's case forming a continuing relationship with local furniture firms for the supply of mirrors. Smaller firms such as the Modern Leaded Glass Company, which did not diversify but concentrated their energies on art glass, went under when the wheel of fashion turned or when tougher times meant fewer purchasers for luxuries like art glass.

8 Unlike the Bogardus and Modern Leaded catalogues, the third copy of the 1909 Official Catalog has no overprinting and no special number. It does, however, carry a hand-lettered title, "Collinwood (sic) West Art Glass Works."7 Collingwood West was a stop on the Vancouver-New Westminster interurban tram line and in the years just before the First World War became a pleasant residential area favoured by small businessmen and working people. No record has been found of an art glass company there nor are any glass artisans known to have resided there. The best answer at the moment seems to be that it was a conceit adopted by William H. Morton of Royal City Glass in New Westminster.8

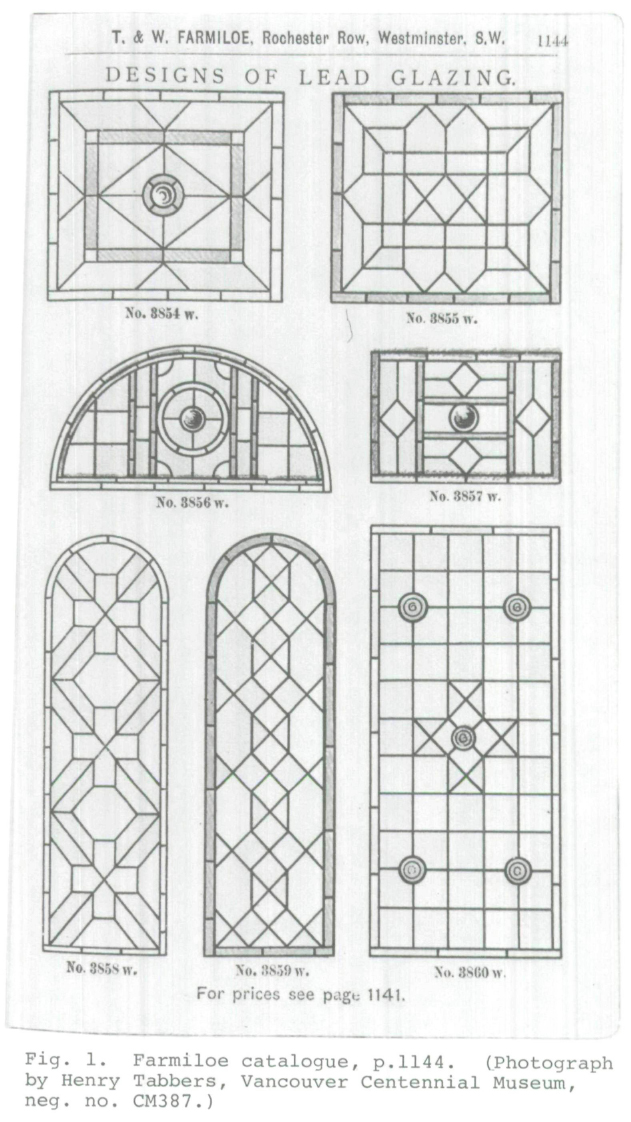

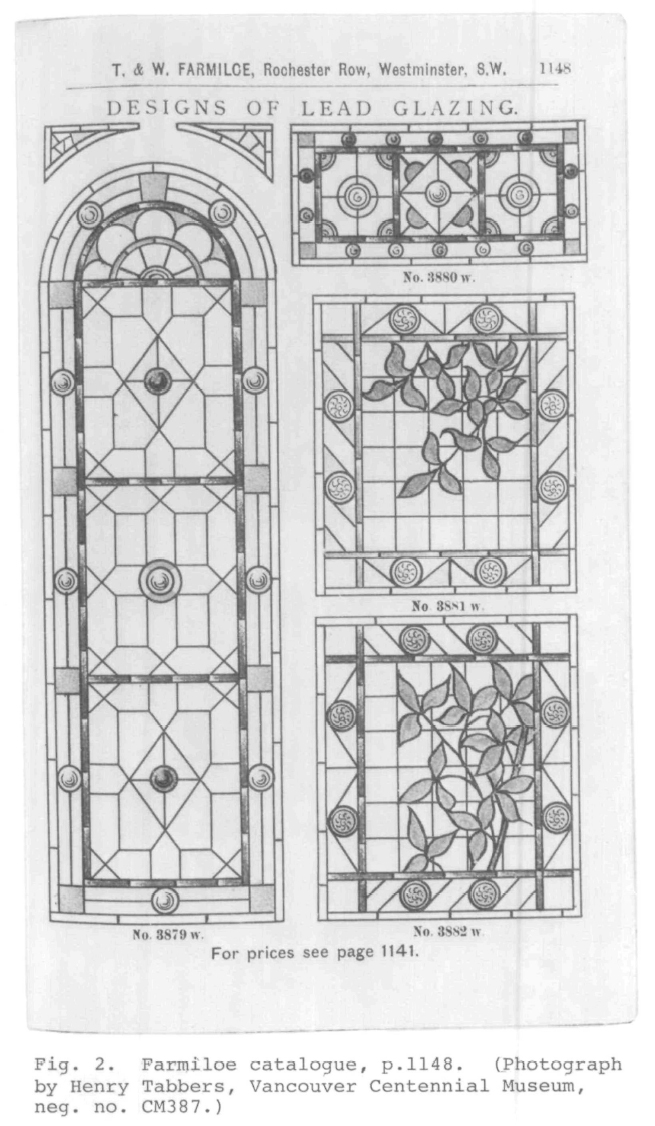

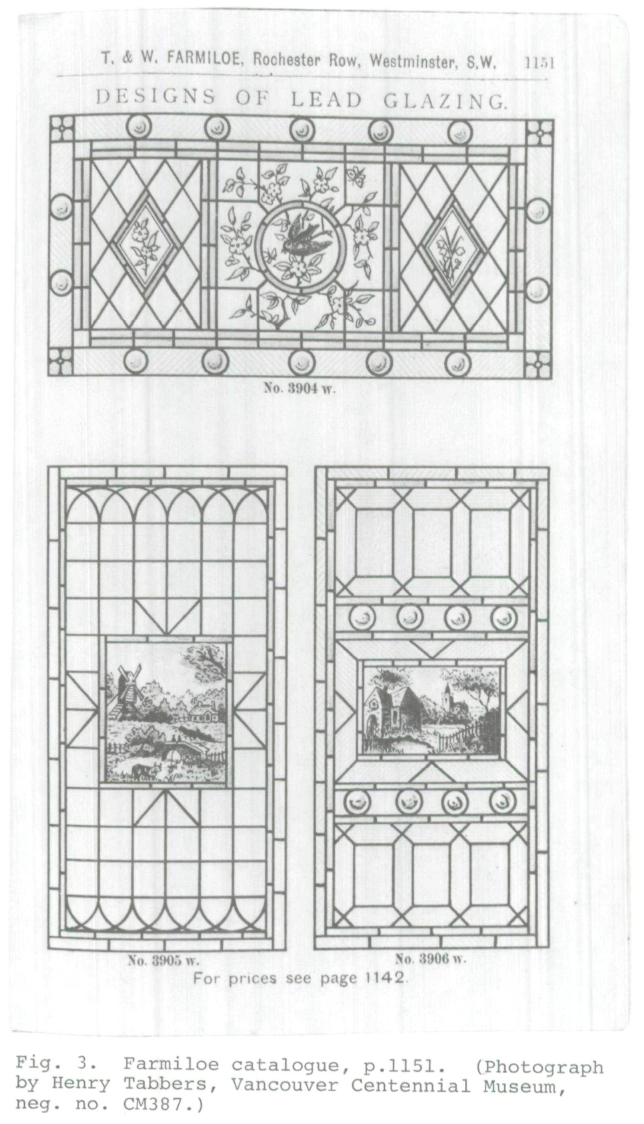

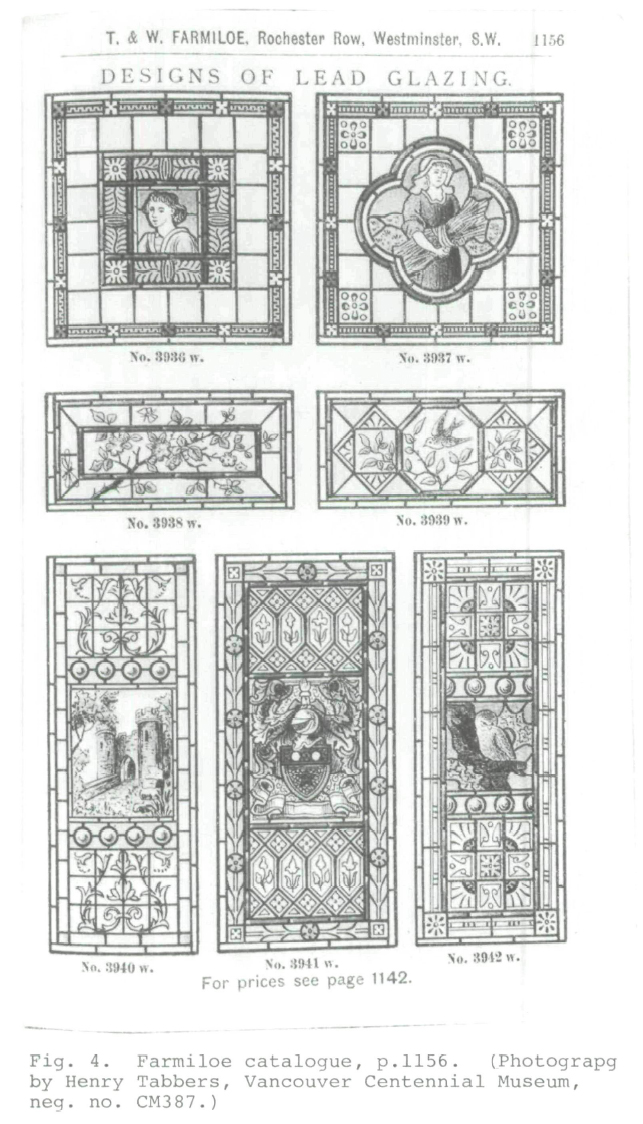

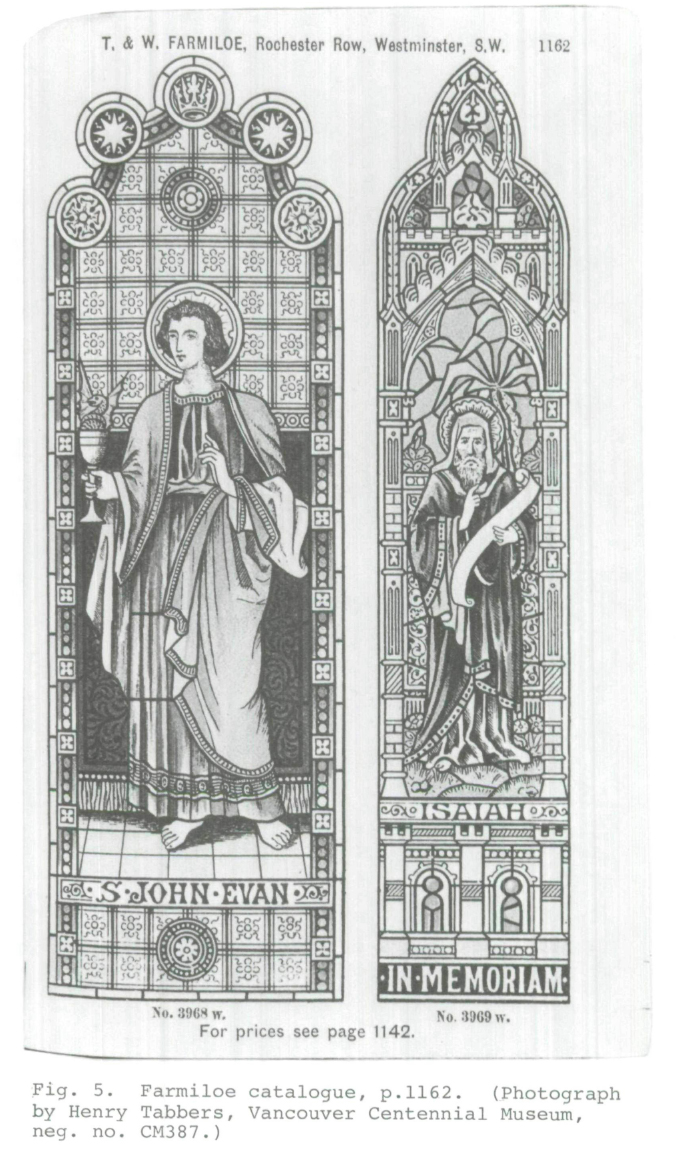

9 The records of the Royal City Glass Company also contain a copy of the 1924 Revised International Art Glass Catalog — Domestic issued by the National Ornamental Glass Manufacturers Association. This particular copy is missing the front cover so it is impossible to tell whether it was overprinted. A complete copy of the same catalogue exists with the stamp of the Western Glass Company.9 This company was founded in 1921 and, although involved in the auto and building glass trade, it specifically advertised the manufacture of art glass as early as 1924.10

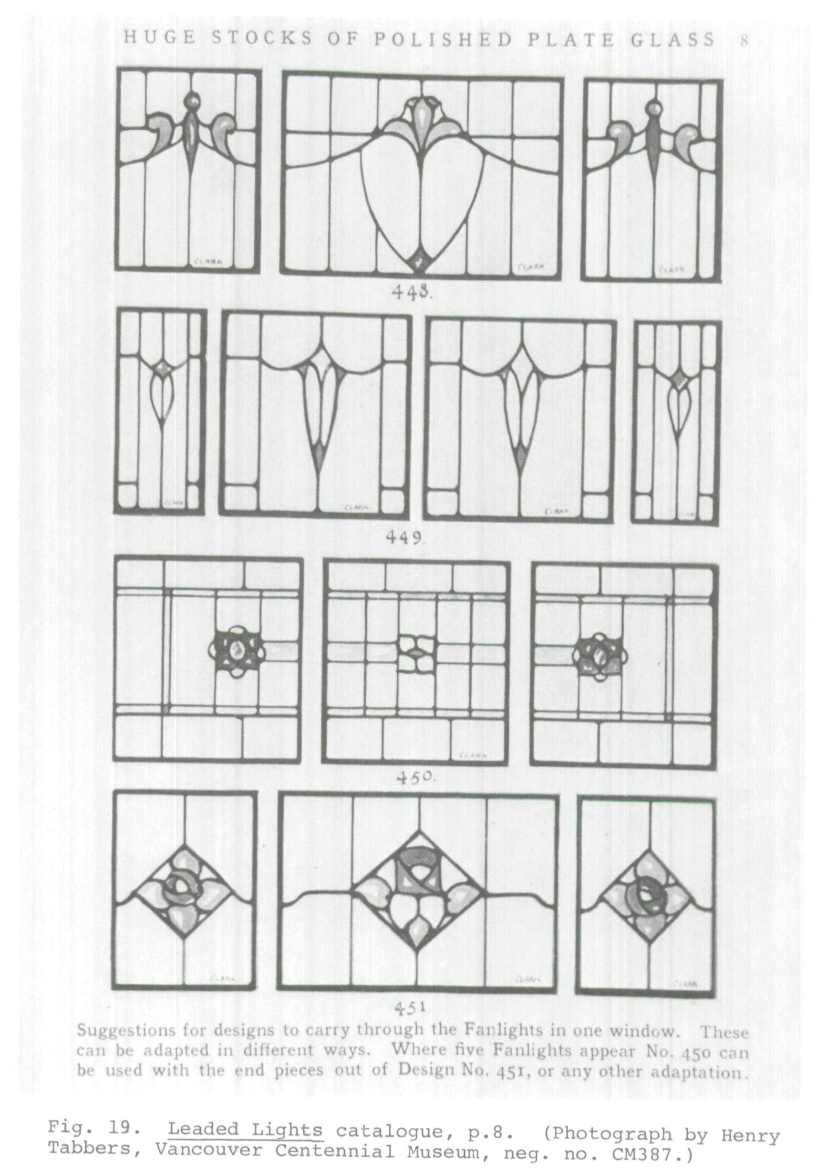

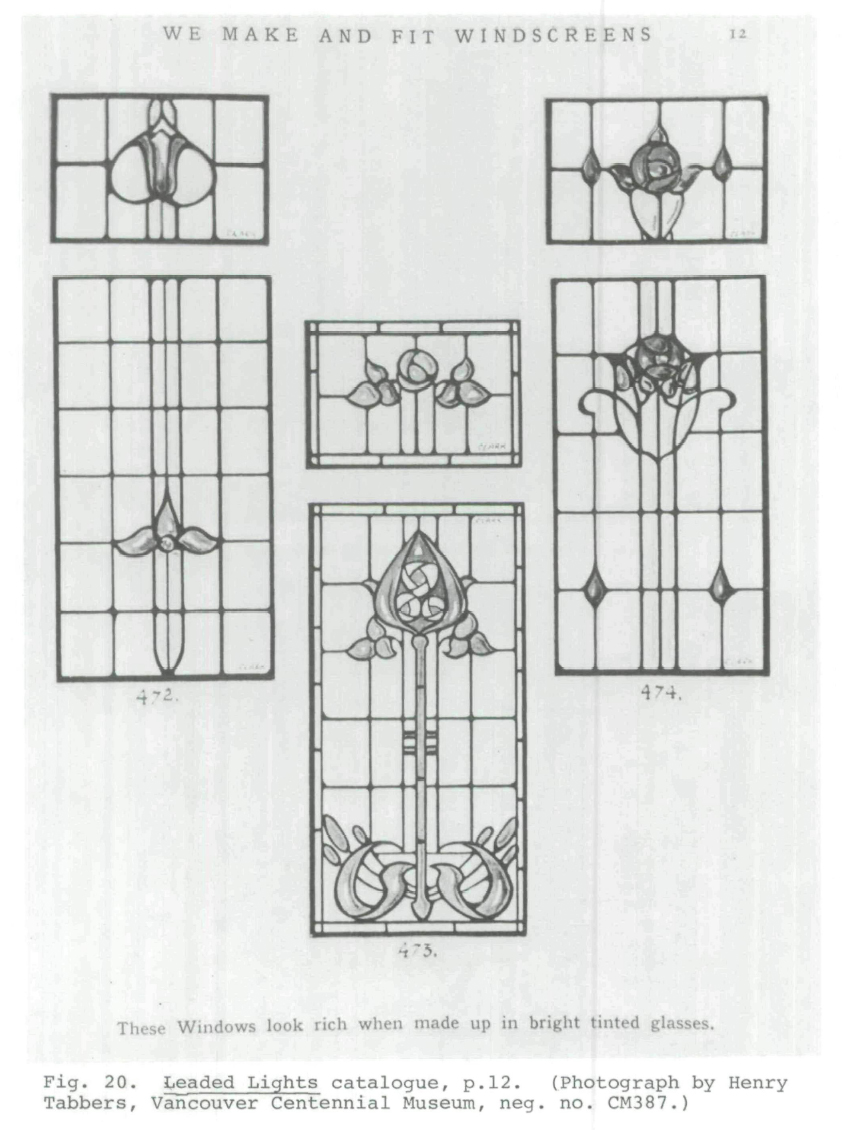

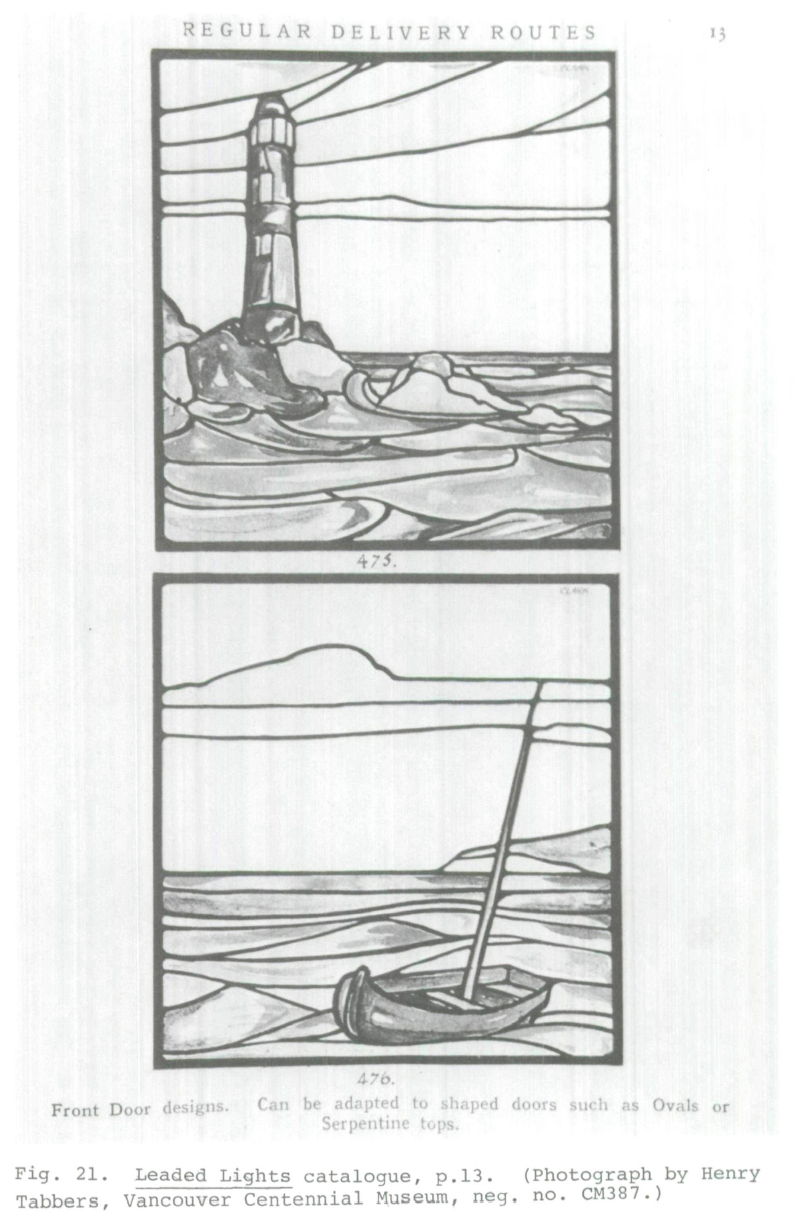

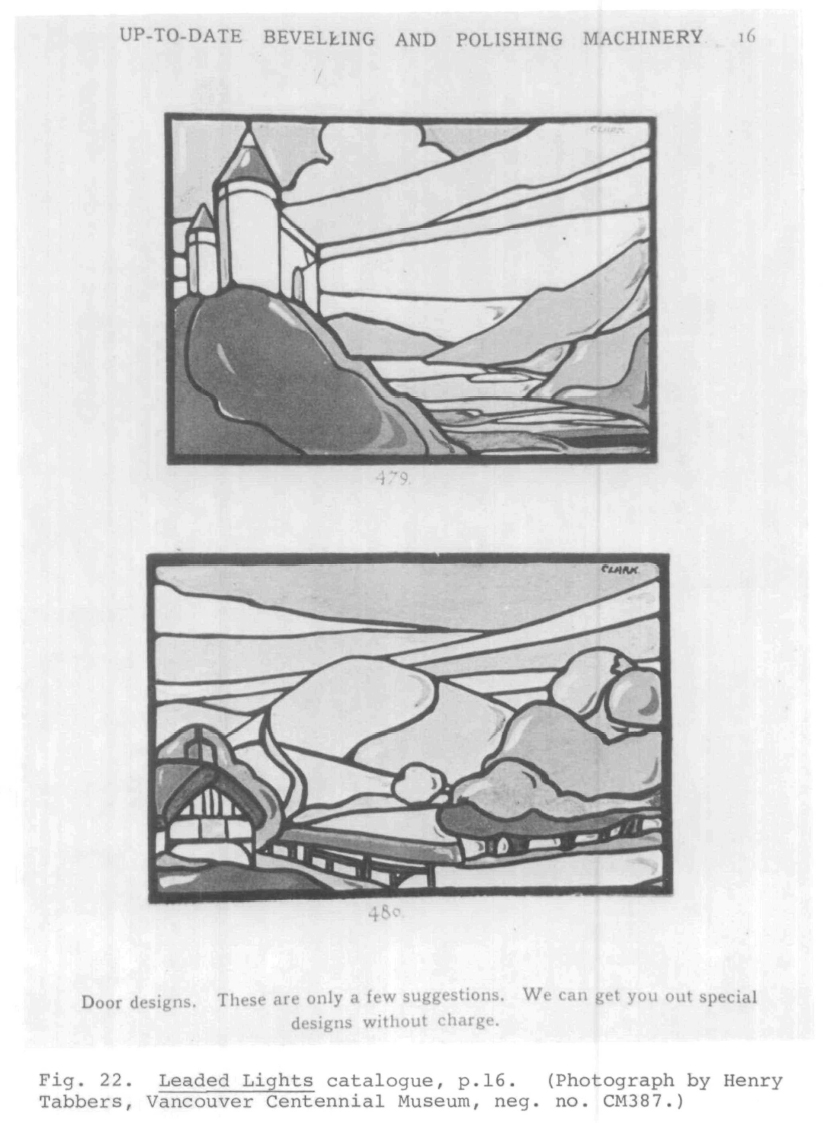

10 Before examining the types of patterns presented in these catalogues, we should consider the two English and one Canadian examples of the same genre which also have a Vancouver provenance. The earlier of the two English catalogues, ca. 1905, is missing the front cover.11 It was almost certainly part of the personal baggage of William Morton when he came from England to New Westminster in 1914. The catalogue was published by T. and W. Farmiloe of London, England, and contains a blend of clear leaded and coloured glass designs in much the same proportions as the American catalogue although the designs themselves are distinctly different. The second and more recent of the English catalogues is a twenty-two-page volume titled Leaded Lights and Stained Glass issued by the London firm of James Clark and Son. It was originally sent to Norman Bajus when he was foreman in the art glass department of Bogardus and eventually came into the possession of John Lamb who worked with Bajus for a while and later had his own firm.12 Although the catalogue is undated it appears to have been published between 1925 and 1930.

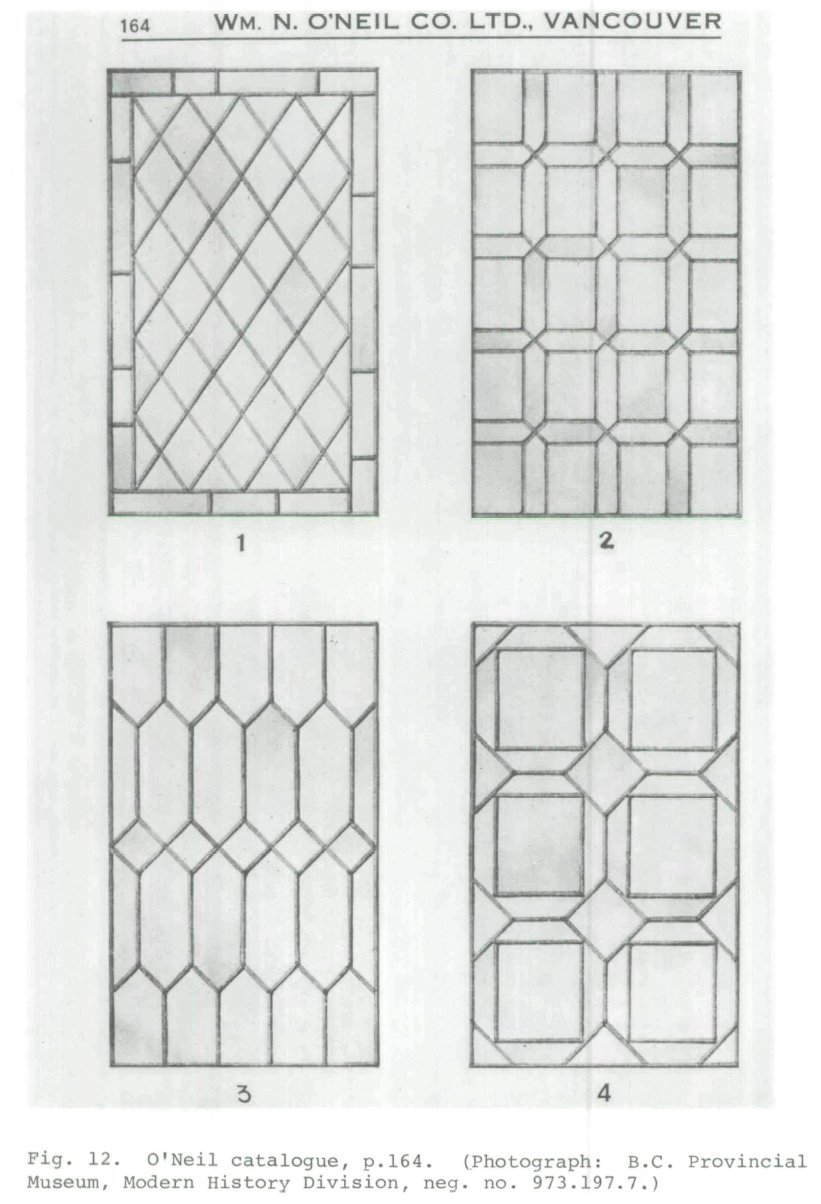

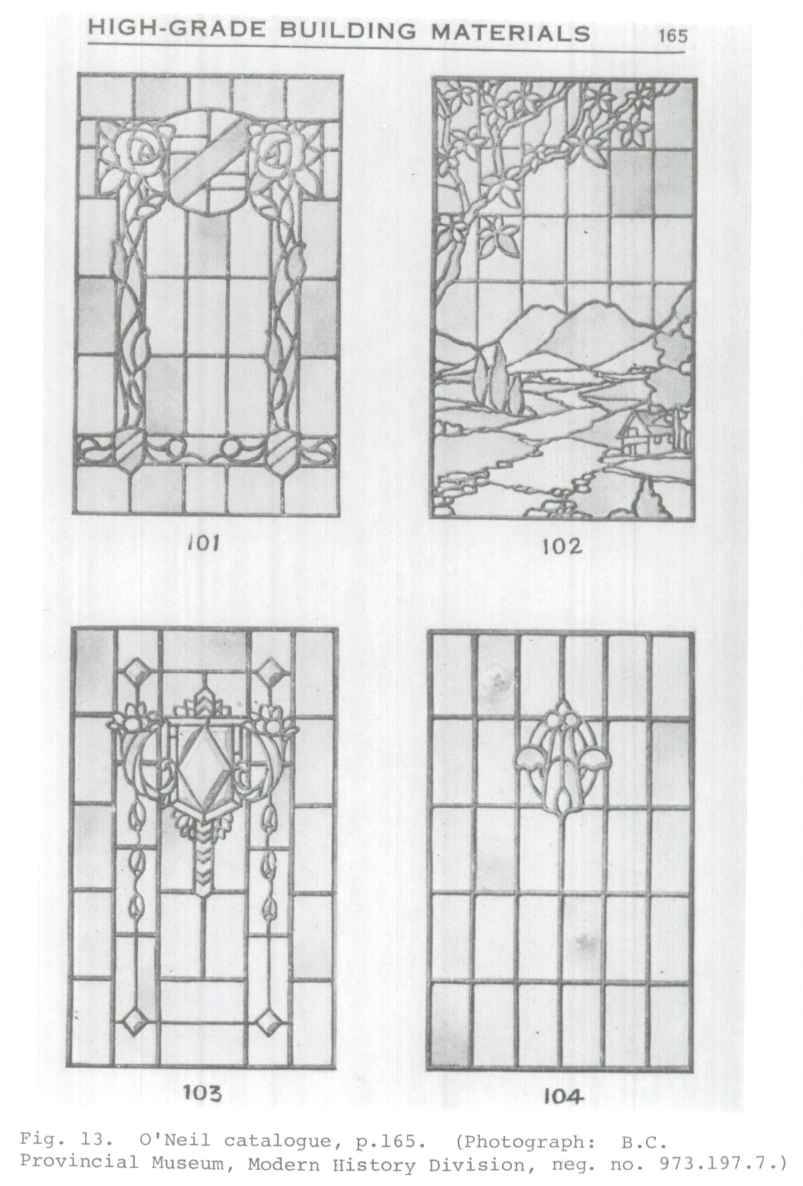

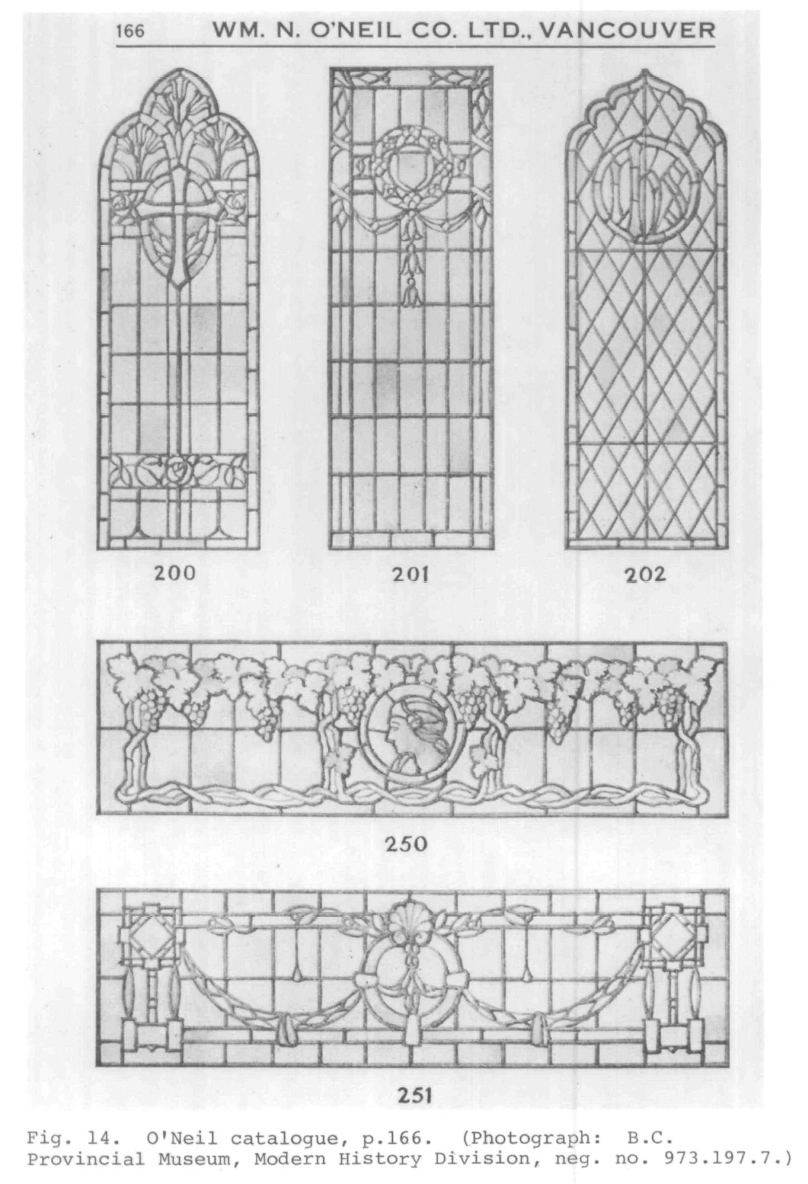

11 The final set of patterns in this group of documents and the only Canadian examples are found on pages 164-66 in High-Grade Building Materials, Catalogue No. 1 issued by William O'Neil and Company of Vancouver and Victoria about 1913.13 In an introduction to these few patterns, the following note appears under the title "Art Glass Studio" (page 163):

The O'Neil firm, founded in Vancouver in 1898, at first did no manufacturing of its own but acted as an agency for the noted Canadian stained and art glass firm of Robert McCausland Limited, Toronto. There is some evidence, however, that by 1910 the company employed artisans in Vancouver and presumably the above patterns were printed in connection with that development.

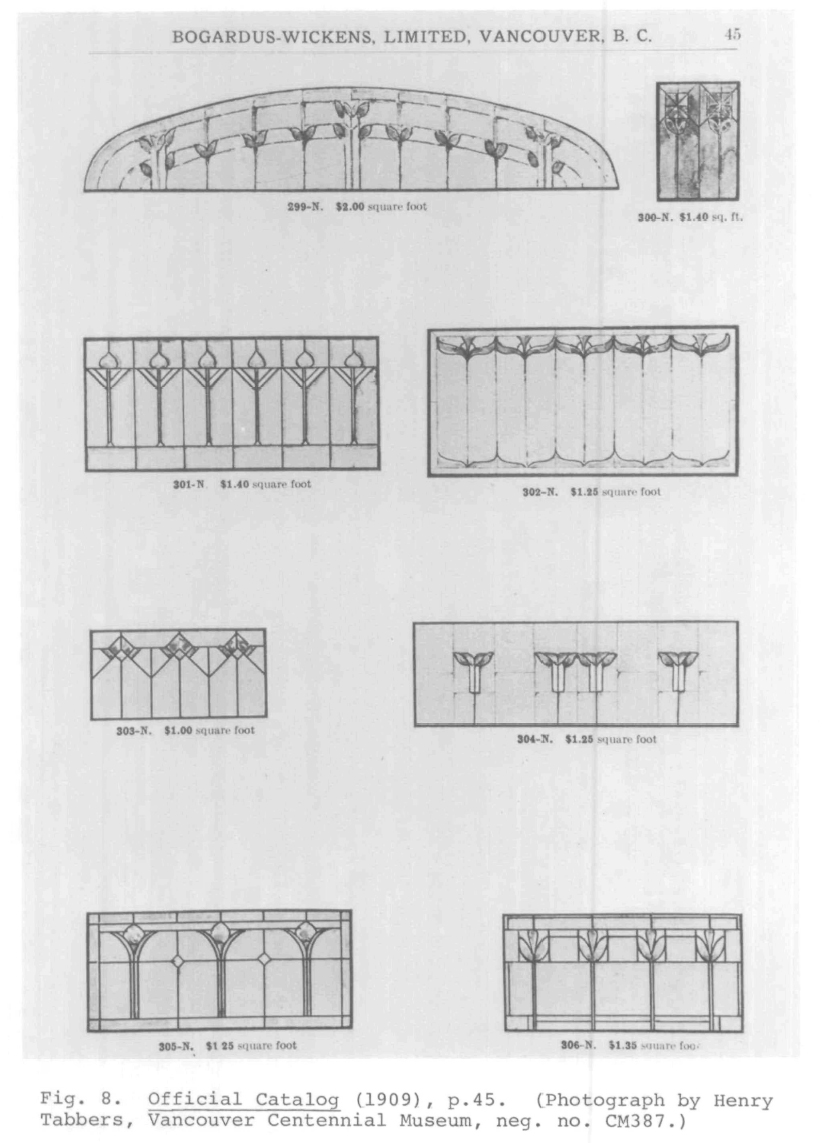

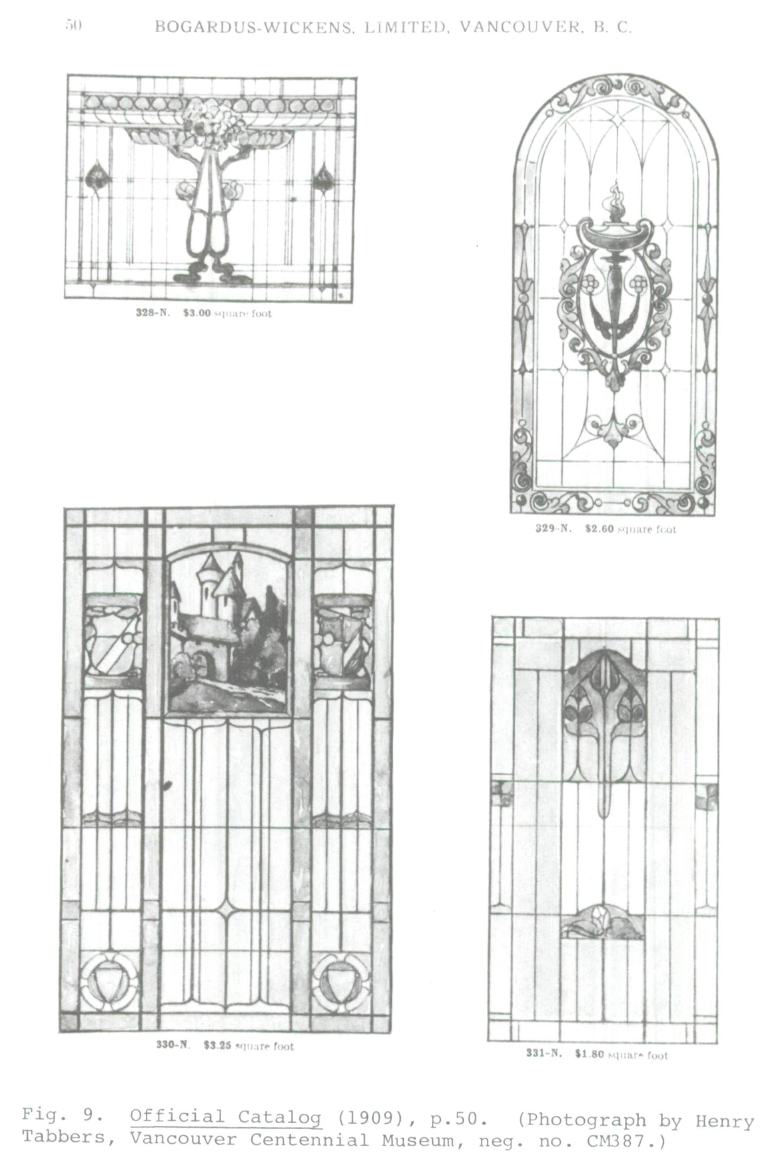

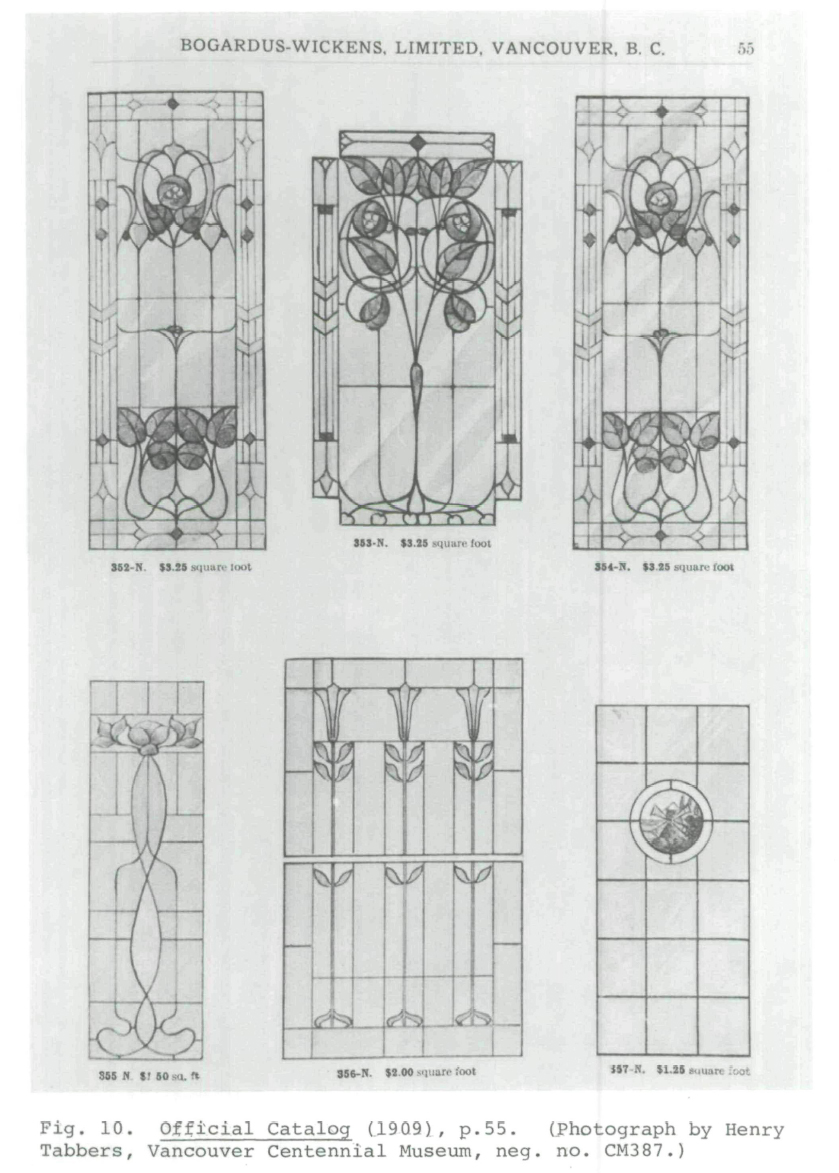

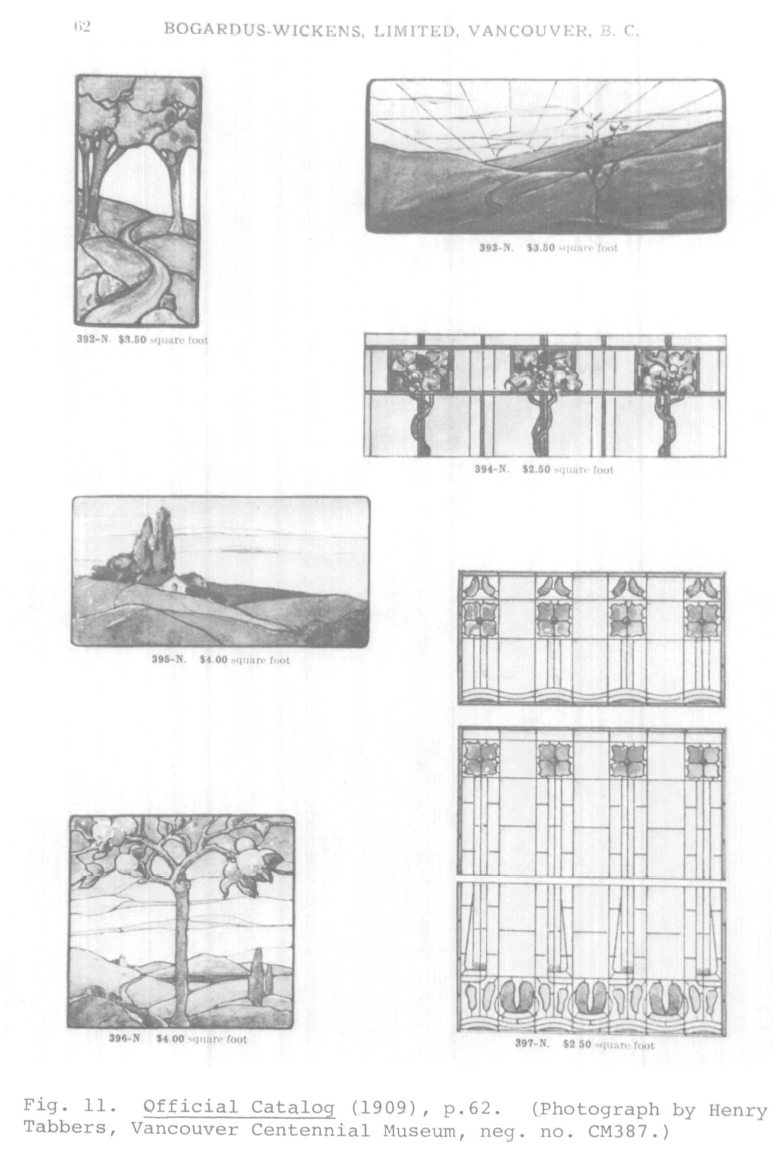

12 A comparison of the various catalogues reveals some very interesting differences between the patterns. Figures 1 to 5 provide a representative sample of designs from the Farmiloe catalogue, presumed to date ca. 1905. Figures 6 to 11 are taken from the Bogardus copy of the Official Catalog of 1909. Figures 12 to 14 comprise the three pages of patterns in the O'Neil catalogue. Leaving aside the question of colour, the English designs are much more angular than the American and the English artists seem much more determined to have a well-defined border around the design. Many of the American designs are reminiscent of the art nouveau style. Roundels or bull's-eyes are frequently included in the English designs as are stained or painted scenic panels or insets which are almost invariably made up in mosaic form. Although the treatment is quite different both groups of artists depend heavily on flowers, other plant forms, and pastoral scenes in their designs. Overall, the Canadian designs tend to be more American than English in tone.

13 In the years after the First World War stylistic differences are narrowed. Figures 15 to 18 are taken from the 1924 Revised International Art Glass Catalog -- Domestic and figures 19 to 22 from the James Clark and Son catalogue. Particularly noticeable is the increased use of curved lines in the English designs and also the use of complete scenes with little or no border.

14 While the question of the stylistic antecedents of the designs in these books is an interesting one, a good deal of research needs to be done before any firm conclusions can be drawn. In advance of this research it is still possible to assess the way in which these books were used in the production and merchandizing of art glass in Vancouver. At the outset it is important to recognize that these books, by their very nature, draw a distinction between the unique commission designed for a specific building and the mass-produced article often made without any particular reference to the building that housed it. In an artistic sense some would claim that this debased the art form. Others might argue that it made excellent economic sense in that it brought a pleasant form of decoration within reach of much larger numbers of people. In this regard it is interesting to recall the reasoning of the creators of the National Ornamental Glass Manufacturers Association catalogue, who hoped their publication would both raise artistic and technical standards and provide more work for the members.14 The twin concerns of economics and art were intimately linked in the expense of building up a stock of good designs. Not every firm which made art glass could afford to employ a qualified designer and not every glass artisan who was technically accomplished was a good designer. Pattern books were undoubtedly one way around this difficulty.

15 There are two basic types of evidence available for analyzing the use of pattern books. Certain documentary and oral history material has been discovered and developed. Of greater long-term importance, but as yet less studied, is the evidence provided by the hundreds of art glass windows still in situ.

16 Fortunately it has been possible to interview a few people who were involved in the art glass business in Vancouver prior to the First World War. Clifford Mason, a native of Dundas, Ontario, came to the city in 1895, left school in 1910 at age 14, and apprenticed with Standard Glass Company. This firm was founded in 1909 or 1910 by Charles Bloomfield, the most experienced glass artisan in the city at that time. Bloomfield, his brother James, and father Henry founded the province's first art and stained glass business, Henry Bloomfield and Sons, in New Westminster in 1891. Burned out by the great fire of 1898 they used the opportunity to move to Vancouver which was quickly becoming the major economic centre in the province. James was a very talented artist and glass designer who supplemented natural ability with training in the United States and England between 1896 and 1898. As it happened, James decided in 1904 that prospects for quality stained and art glass work in the city were limited and the firm broke up. During this brief period, however, Charles must have benefitted greatly from the technical and artistic expertise of his brother and probably carried this experience into the firms which he subsequently worked for and the one which he founded, Standard Glass.

17 Clifford Mason recalled that Vancouver firms relied heavily on pattern books for most of the domestic work. The books were used as a guide to the general appearance of the window and frequently the artisan would change a line or two or choose different colours. Mason was adamant that these patterns and changes were quite ordinary. Anything out of the ordinary, either in design terms or in terms of requiring staining of the glass, was a special order. Mason claimed that at the time he apprenticed with Standard Glass in 1910-11 the men in the art glass section of the firm were the only ones in Vancouver capable of doing this specialized work.15 Subsequent research suggests that this claim is not completely accurate. Arthur P. Bogardus's son, F.W. Bogardus, remembers that his father recognized the local market demand for more elaborate stained glass in homes and churches and in 1911 hired an English artist, F. Louis Tait, to enable the firm to respond to the demand. Tait was a stained glass designer and painter whose career in that field in Vancouver extended into the early 1930s.16

18 E. Roy Wilson, a brother-in-law of Arthur Bogardus who began working with the Bogardus firm in a clerical capacity in 1908, confirmed Mason's impressions of the role of the pattern book and commented additionally on the central role of the sash and door companies and contractors in the process of choosing designs. According to Wilson some people did come into the Bogardus offices and order windows from the office copy. In the majority of cases, however, the orders came from the contractors or the sash and door factories, all of whom had copies of the Bogardus overprint of the Official Catalog. The customer made his choice through the sash and door companies. Wilson also thought that changes in pattern detail and colour were quite common.17

19 This limited evidence indicates that the pattern books were regularly used but that the client, contractor, or artisan freely altered the published design. Mason even remarked on the skill exhibited by W.W. Roberts of the Modern Leaded Company at "inventing things and changing patterns" from pattern book designs.18 Obviously, in terms of the eventual overall look of windows in Vancouver, the amount of alteration could markedly affect the end result.

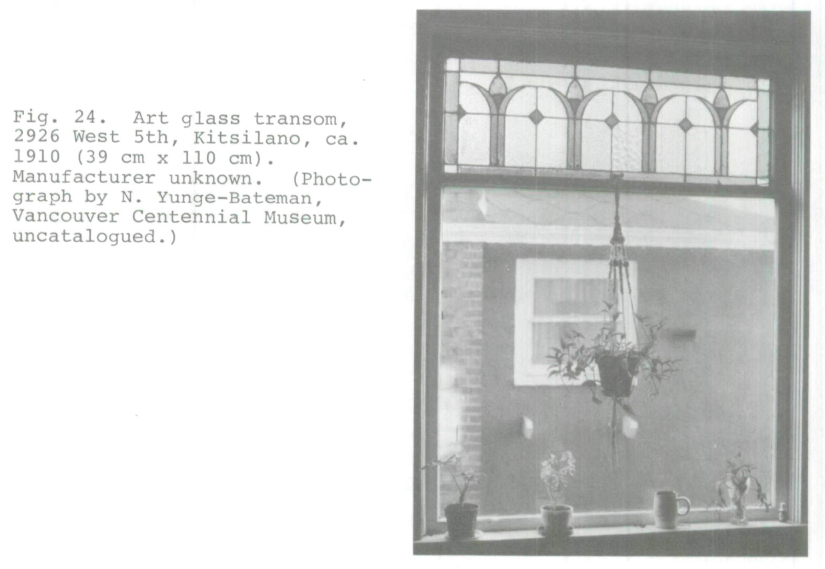

20 This raises the question of what field research reveals. Several points need to be made at the outset. Domestic art glass, in Vancouver at least, was almost never signed. The exception which proves the rule is the very large stained glass landing light done by James and Charles Bloomfield in 1901 for "Gabriola," the West End mansion completed in that year for B.T. Rogers, owner of the B.C. Sugar Refining Company. Yet in most cases, even when the windows involve considerable amounts of painting and staining, they are not signed. This contrasts markedly with church windows which almost always carry the name of the firm or the artist-painter in the lower right-hand corner. The absence of signatures may represent the distinction between artist and artisan, between work that is the result of one person's imagination and skills and work that involves two or three people of differing skills. It may also be true that most of these windows were viewed, at best, as craft productions not worthy or important enough to be identified as the work of an individual. All of this means that attributions of one window or another to a particular firm or craftsman are nearly impossible.

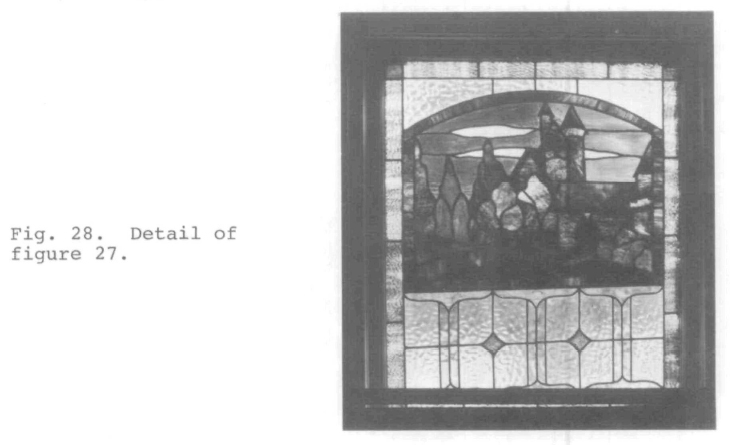

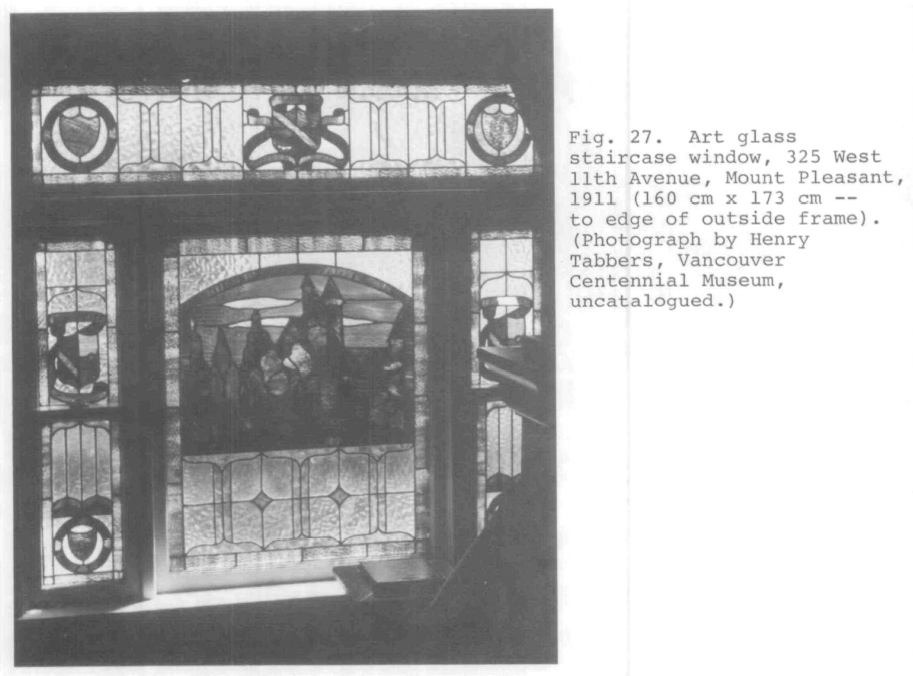

21 Added to this is the problem of the current state of field research. A more complete answer to the question of the relationship between pattern books and final production will only be possible with more systematic study of what now exists in Vancouver homes. At a very rough estimate three to five thousand city homes and apartments contain at least one art glass window. At present only ten to fifteen percent of these have been described verbally and photographs have been taken for not more than two hundred. This means that a comprehensive statement on any similarities between Vancouver art glass windows and pattern book designs cannot yet be given.

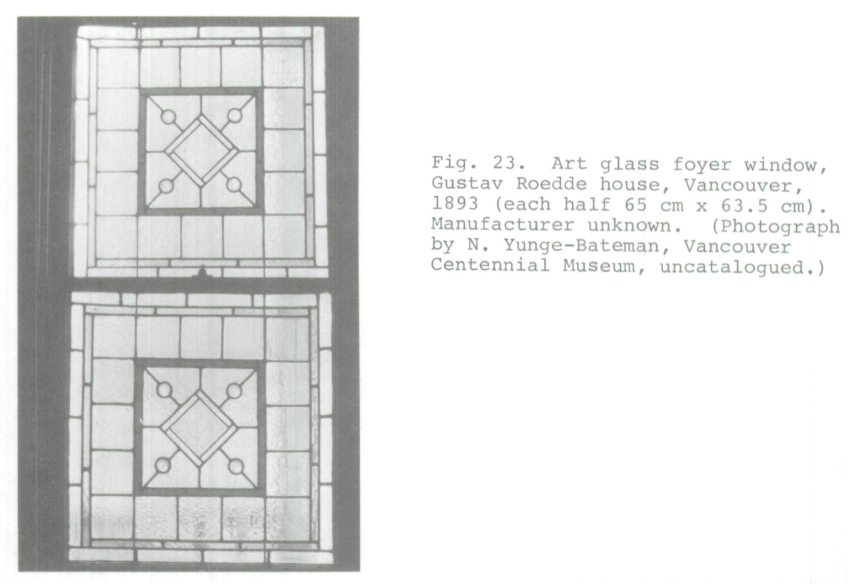

22 However, the field evidence suggests certain conclusions. Little glass now survives that seems allied to the design spirit of the Farmiloe catalogue. A very interesting exception is a window (figure 23) which is found next to the front door of a West End house built for Gustav Roedde, bookseller and stationer, in the summer of 1893. The glass is mostly white marbellized, with narrow bands of light blue near the frame and red bands forming the central square; at the centre is a pressed glass lozenge of pale mauve, carrying a floral design. The glass has the angularity of some of the Farmiloe designs, but is also somewhat reminiscent of the Toronto art glass windows of the same period which have been discussed by Alvyn Austin.19 In fact, it is quite possible that these windows were produced in Toronto, although Henry Bloomfield and Sons Limited was in operation at the time the Roedde House was built. Unfortunately, there are no known examples of the Bloomfield firm's work that can be dated to this period and so we do not know whether this window is characteristic of its early work. The larger question of which styles were the dominant ones in the 1890s in Vancouver is difficult to solve. Most of the pre-1900 houses in the city's oldest residential neighbourhoods have been demolished and so few examples now survive that it is impossible to perceive trends.

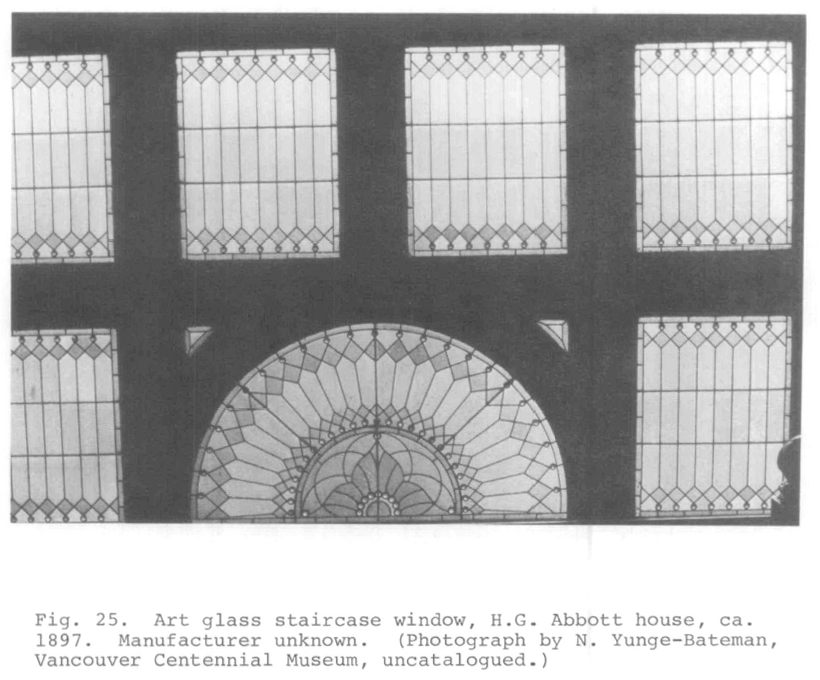

23 One of the few other examples of Vancouver glass which can be positively dated before 1900 is a window (figure 25) made to light the main staircase in a house built ca. 1897 for H.G. Abbott, an official of the Canadian Pacific Railway. It incorporates some of the English geometric style with a nod in the direction of art nouveau curves; the colouring is quite muted, with large expanses of clear marbled glass, yellow diamonds, and pale purple areas in the central part of the fanlight together with pale purple borders.

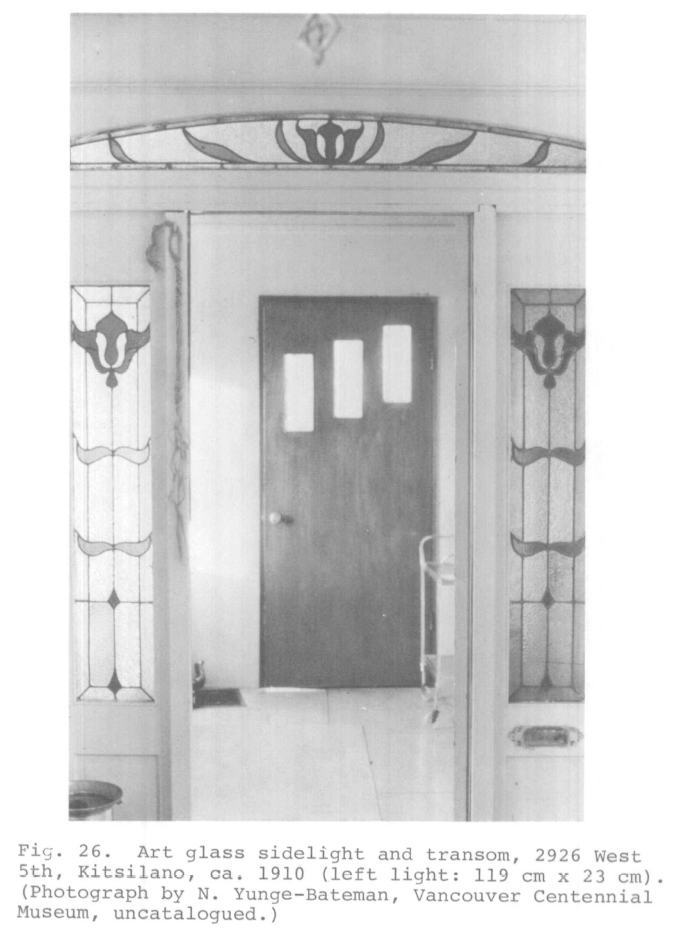

24 In the twentieth century parallels between field evidence and some pattern book designs are more obvious and extensive. Between 1902 and 1912, when the city was expanding very rapidly, the fashion for domestic art glass reached a peak. In this era similarities between actual windows and pattern book designs can be found for both simple and elaborate designs. Figure 24 is a transom light from what was originally the parlour at 2926 West 5th Avenue, a house built ca. 1910 in the then developing residential neighbourhood of Kitsilano. It is remarkably similar to design 305-N in the 1909 Bogardus Wickens and Modern Leaded Glass overprints of the Official Catalog (figure 8).20 The heads of the stylized flowers are green in the window and red in the catalogue and the borders in the window are a more vivid green, otherwise the two are remarkably similar. The similarity is less striking but still apparent when comparing the sidelights and transom from the front door (figure 26) and design 356-N from the 1909 catalogue (figure 10).21

25 Larger and more complex windows also provide evidence of having been made by craftsmen familiar with the 1909 pattern book. Figures 27 and 28 show a photograph and a detail of the east landing window in a home built in Mount Pleasant in 1911 for Joshua-Wakefield, a developer.22 Although the window is wider and divided into four sections, it echoes in colour, leading, and symbolism the pseudo-heraldry and the castle with romantic and pastoral allusions of design 330-N in the 1909 catalogue (figure 9).23

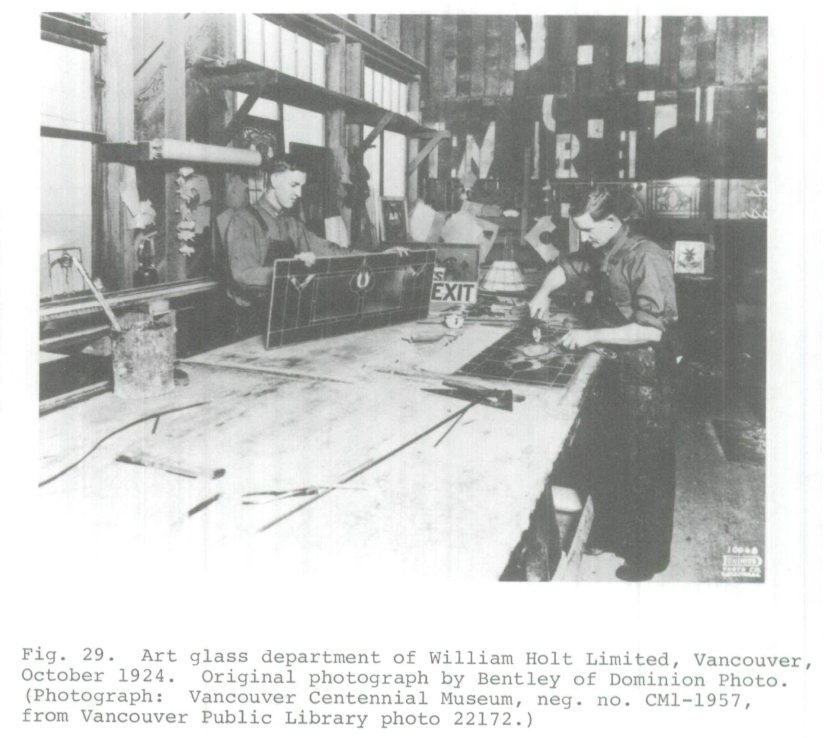

26 A further example of these kinds of parallels can be taken from the post-First World War period when use of art glass in Vancouver homes was diminishing but when it was still favoured by many of the architects and contractors who designed and built three-storey apartment buildings in the West End, Kitsilano, and South Granville. Figure 29 shows art glaziers Frank Hamilton (on the right) and Jack Lamb working in the art glass department of William Holt Limited at 426 - 436 West 2nd Avenue in 1924.24 The art glass panel held by Jack Lamb is similar to designs found on page 24 of the Revised International Art Glass Catalog — Domestic of 1924 (figure 18).

27 What can be concluded from this brief review? Field evidence suggests that some of the local firms and their craftsmen did use these catalogues as sources of design. Of the pattern books thus far located, it is the American publications which predominate and which seem to provide more of the inspiration for patterns. This is interesting in itself since research has also revealed that a majority of the glass artisans working in Vancouver before 1940 were British or continental European by birth and training.

28 A number of aspects of the pattern book question remain to be tested and the points raised here must await further field research for clarification. It may be that archival research will suggest a greater place for English and eastern Canadian design for the period 1887-1902. Analysis of photographs may also be helpful in bridging the gaps left with the destruction of a large percentage of pre-1900 homes. During this period Toronto art glass firms, through agents like O'Neil or directly, may have had a much larger share of the local domestic market than they later enjoyed even discounting early competition from Henry Bloomfield and Sons.

29 Systematic field study would probably isolate those pattern book designs which were local favourites as well as establish the degree to which the city's glass artisans developed a local style based on certain designs and colours. At the same time further research should also identify more firmly the stylistic antecedents of the pattern books in use in Vancouver. The final result would be a definitive statement on the nature of local art glass window design, its design antecedents, its relationship with what was produced elsewhere, and an assessment of the local product as a distinctive regional artistic development. In the meantime the discovery that English and American pattern books were used in some fashion in the production and merchandizing of local art glass windows should be compared with the experience of other Canadian cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7 Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9 Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10 Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11 Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12 Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13 Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14 Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15 Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16 Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17 Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18 Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19 Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 20 Display large image of Figure 21

Display large image of Figure 21 Display large image of Figure 22

Display large image of Figure 22 Display large image of Figure 23

Display large image of Figure 23 Display large image of Figure 24

Display large image of Figure 24 Display large image of Figure 25

Display large image of Figure 25 Display large image of Figure 26

Display large image of Figure 26 Display large image of Figure 27

Display large image of Figure 27 Display large image of Figure 29

Display large image of Figure 29