Articles

Bottles in the Place Royal Collection

Une bonne partie des objets trouvés sur les anciens sites coloniaux français au Canada est constituée de vieilles bouteilles de vin et de spiritueux. Sous les auspices du Service de l'archéologie et de l'ethnologie du ministère des Affaires culturelles du Québec, des études archéologiques de la Place Royale, secteur de la basse ville de Québec, contribuent à faire la lumière non seulement sur des questions relatives aux bouteilles en Nouvelle-France, mais aussi sur la production, les formes et les usages des bouteilles françaises aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. L'auteur se sert d'une gamme d'indices contemporains, y compris des peintures, des techniques de fabrication, des conditions économiques et des échantillons de marchandises, pour avancer des hypothèses quant aux origines et aux usages des bouteilles trouvées lors des fouilles de la Place Royale et pour soulever des points qui appellent des recherches plus approfondies. [Une traduction française de ce texte sera publiée avec d'autres articles dans la série "Dossier," publication de la Direction générale du patrimoine, Ministère des Affaires culturelles du Québec, en 1979.]

1 Old wine and spirit bottles constitute a good part of the artifacts found on former French colonial sites in Canada. But unlike the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century bottles of some countries, especially those of England, which have been the focus of numerous publications, early French bottles have received inadequate attention. Indeed, basic but complex questions still need exploration. When was the wine bottle first introduced in France? How did it evolve over time? In what ways do French bottle styles relate to other Continental forms?

2 Archaeological studies at Place Royale, an area in the lower town of Quebec City occupied since 1608, are helping to provide answers to those questions.1 Working under the auspices of the Direction de l'archéologie et de l'ethnologie, Ministère des Affaires culturelles du Québec, excavators have unearthed hundreds of bottles and glass fragments, some of which had lain buried for nearly three centuries.2 The bottles include examples of the common types made in France and used in her colonies in the first half of the eighteenth century. Some of them, moreover, rank among the earliest wine bottles yet found.

Shaft-and-Globes

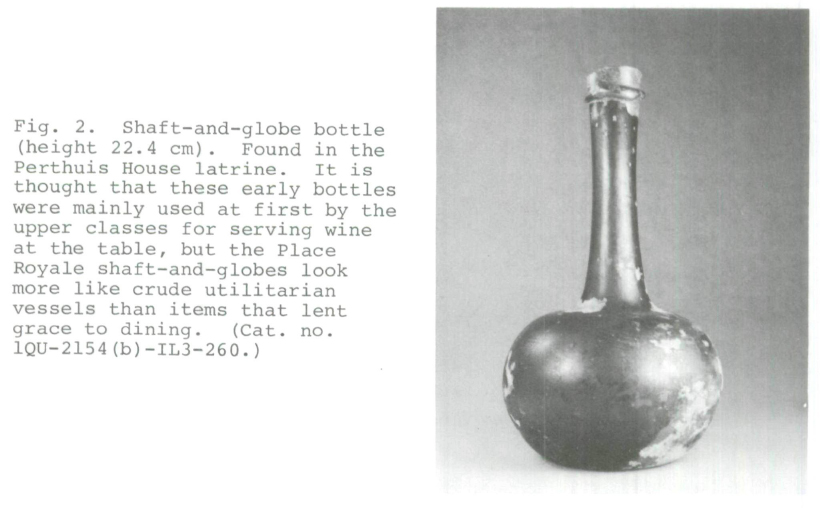

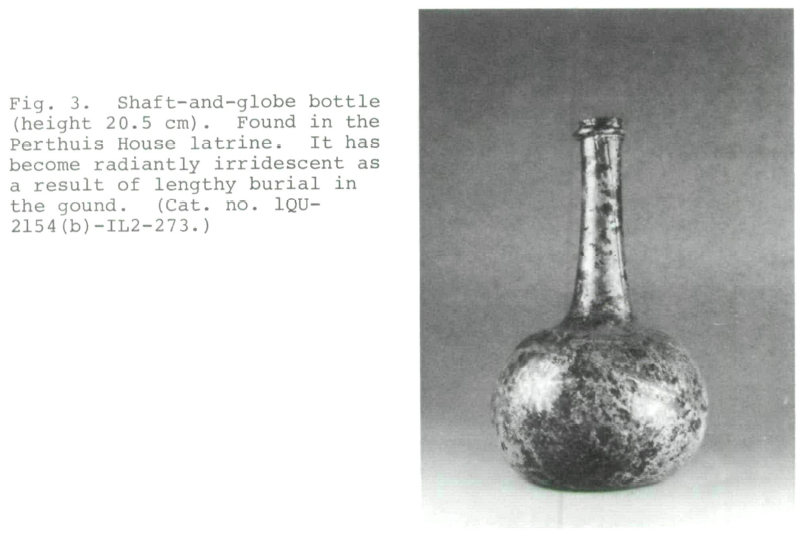

3 The oldest and most intriguing bottles in the Place Royale collection have spherical bodies surmounted by long, slender necks — a type which collectors call shaft-and-globes. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show three originally light green specimens that came from the bottom strata of a latrine dug in 1682 and shut in 1759.3 Their shape is characteristic of the first glass wine bottles that were developed in some Continental countries, among them Belgium and the Netherlands, and in England in the second quarter of the seventeenth century.4

4 Compared with their English counterparts the three Place Royale shaft-and-globes appear fragile and crude. Their makers used a simple technique that involved little more than blowing a thin-walled glass bulb and adding the least finishing touches. The bottle lips were re-melted barely enough to blunt the sharp edges that resulted from shearing the neck from the blowpipe. To form the string-rims, which were used to tie down the cork-stopper, thin cords of glass were wound sloppily around the necks only 0.5 to 1.5 centimetres below the mouths of the bottles. The bases were pushed up slightly, allowing the ball-shaped vessels, which range between 20.5 and 27.2 centimetres in height, to stand upright and removing from surface contact the glass scars left by either a blowpipe pontil or a plain glass-tipped pontil.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 35 Their origin remains unknown. It seems safe, though, to rule out the likelihood that the New France colonists made the bottles themselves: researchers have found no evidence that suggests the French ever tried to make glass in Canada.5 Besides, the French government frowned upon manufacturing in the colonies, preferring to keep them as sources of raw materials and as markets for finished goods. This dependence upon France by Quebec for supplies of manufactured articles did not mean, however, that every imported item, including bottles, was French.6

6 Descriptions of bottles made in France and shipped to the colonies in the seventeenth century fail to resolve the question. Warren Scoville states that throughout the seventeenth century nearly all French bottles were so fragile that they had to be wrapped in strong straw jackets.7 James Barrelet agrees with Scoville and says that in seventeenth-century France the standard wine bottle resembled a flattened glass gourd encased in wicker for protection.8 But Frank Davis thinks that at the start of the eighteenth century French bottles were shaped like an onion and had a long neck, looking like a modern decanter.9

7 Davis's description fits, more or less, the Place Royale shaft-and-globes, but his dating raises questions. For instance, did French bottle shops continue to make into the eighteenth century a style that in other countries had given way by 1700 to several sharp and drastic changes? In England, to cite the clearest example, the long-necked, bulbous wine bottle ceased to be made after the 1660s. Furthermore, it is difficult to find evidence of the shaft-and-globe's use in France, let alone proof of its manufacture there, although a pre-1673 painting (Pierre Boucle, Le poulet mort, private collection, Paris) does show a bottle similar, except for a shorter neck, to the Place Royale shaft-and-globes.

8 Barrelet and Scoville maintain that throughout the seventeenth century and for at least a decade or two into the eighteenth the common glass wine vessel in France remained the wanded bottle. That form, which was used primarily as a serving bottle because of its fragility, enjoyed widespread popularity in the wine-producing areas of Europe from the first half of the sixteenth century, or perhaps even earlier, to well into the eighteenth. Lubin Baugin's painting Le dessert de gaufrettes (ca. 1650; Musée du Louvre, Paris) features a wicker-covered bottle that resembles the modern Chianti bottle, while Antoine Watteau's scene L'amour au theatre français (ca. 1715; Staatliche Museum, Berlin-Dahlem) shows the other chief type of wanded bottle — shaped like a flattened gourd or a tennis racket. The production and use of the wanded bottle was identified closely enough with France that early eighteenth-century English documents list even those made in England as "long-necked French quart bottles."10 were easily broken and because their poor quality glass deteriorates rapidly in the ground, few pieces of wanded bottles have been found in Canada.

9 In the seventeenth century French bottle shops were restricted from making little else besides wanded bottles and other delicate vessels because their wood-burning furnaces could produce only light green or pale blue glass that formed thin-walled bottles. Still, French glassblowers could have experimented with new forms such as those represented by the Place Royale shaft-and-globes which do appear to be products of wood-fueled shops. But the success of the shaft-and-globe bottle and its subsequent forms, in some countries, in supplanting traditional wine containers, such as those made of stoneware as well as those that needed a protective covering, was based on coal. Glasshouses that used coal could make bottles, in large numbers and at low cost, that were strong enough to be used for storing and transporting wines and spirits. French glass factories lagged far behind English shops in adopting that technology. Therefore, if the shaft-and-globe form was made in France in the second half of the seventeenth century, it would have represented no improvement in quality or applicability over other French bottles, specifically the wanded bottle, with which it would have had to compete for consumer preference.

10 Excavations in French-occupied, seventeenth-century sites in eastern Canada have yielded few clues to unravelling the mystery of the origin of the Place Royale shaft-and-globes. At Beaubassin, Nova Scotia, an area settled by the French in the 1670s, and at Castle Hill, Newfoundland, a site held by the French from 1693 to 1713, no bottles similar to the Place Royale shaft-and-globes were found, nor even any fragments of seventeenth-century wine bottles that can be attributed with certainty to France.11 In fact, most of the seventeenth-century and early eighteenth-century wine bottles found on those sites are English.

11 The predominance, on seventeenth-century French sites, of English and other non-French bottles, like the two in figures 4 and 5, has several explanations. Because its bottle industry was relatively weak in the seventeenth-century, France, which had diverse trading links with neighbouring countries, imported bottles both full and empty. Even though French merchants generally shipped wines and spirits in wooden casks, they often bottled the finer quality and more expensive vintage wines and liqueurs, preferring to use, no doubt, stronger imported bottles.12 Also, despite restrictions on trade (French commercial policy stipulated that goods from other countries had to be sent first to France before they could be legally exported to the colonies), New France exchanged goods directly with areas under foreign jurisdiction, especially New England. Following intricate trading networks, bottles from various countries could have found their way to Quebec City.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 512 The origin of the Place Royale shaft-and-globes remains moot largely because little is known about the products of seventeenth-century glass factories in France and in Europe generally.13 Until more is learned about the bottles made, including the less common forms, the only sure fact about the Place Royale shaft-and-globes is that they were found in a former French colony in a late seventeenth-century context.

French Bottlemaking "à la façon d'Angleterre"

13 During the first half of the eighteenth century the French bottle industry transformed itself into a large-scale maker and exporter of thick-walled glass bottles which overtook wanded bottles as the common wine bottles in France. This "revolution" came about chiefly through the introduction of coal-fueled furnaces, a technological innovation encouraged by government measures to prevent deforestation and borrowed from English manufacturers who had converted from wood to coal in the early seventeenth century. Compared with the "common green" and fragile glass made in shops that used wood, the glass produced in furnaces fired by coal was coarser, darker, and stronger.14 The French described the glass as "à la façon d'Angleterre."

14 Gaspard Thevenot built the first coal-fueled bottle factory in France in 1709. By 1720 France had four such shops, by 1740 at least fourteen, and by 1790 approximately forty-five. Only three years after the start of the first of those shops a report commented that the Thevenot venture "enjoys the greatest success... its bottles already are as good as those made in foreign countries...."15

15 Just what those early dark bottles looked like is uncertain. Barrelet thinks that they had big bellies like an onion ("ventre comme un oignon"), resembling the squat form (figure 5) which was made in England during the first quarter of the eighteenth century and which was copied on the Continent.16 Once again, however, excavations at early eighteenth-century French sites in Canada provide few pieces helpful in solving this puzzle.17 In any case, as the English wine bottle began to evolve in the 1720s towards the shape of a mallet, the French abstained from following English forms the way other Continental countries seem to have done. Instead they developed their own style of cylindrical bottle, presumably so fitting to French needs and tastes that it changed little throughout the rest of the century.18

16 Coal-fired factories produced their specialty — the dark wine bottle — abundantly and cheaply. A shop with a single furnace could blow between two and three hundred thousand bottles annually. By 1740 one large factory at Sevres was turning out well over one million bottles a year. In the period 1725-50 the wholesale price for 100 dark bottles varied little, from 18 to 24 livres.19

17 All levels of French society, comprised then of approximately twenty million people, took to using the dark bottle. Tavern keepers, wine merchants, and shippers favoured it, the very colour of which they saw as a mark of superior strength and quality. Wine lovers came to demand it, especially as their palates learned to appreciate that wines keep and mature supremely better in tightly-corked bottles than in casks. One bottlemaker observed in 1753 that:

18 As the increased preference for bottled beverages spread to French colonies in the New World, merchants responded by exporting far more wine and brandy in bottles.21 Each year through the ports of Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Nantes, and Rouen alone they shipped between forty and fifty thousand bottles and jugs both full and empty. The Intendant of Bordeaux wrote in 1751 that the local merchants "need more bottles at present than ever before because many inhabitants of the isles of the New World, having become wealthier, have also become more self-indulgent, and they demand that the better and older wines be bottled."22 Several dark bottle shops sprung up around Bordeaux which, together with La Rochelle, emerged in the eighteenth century as one of the major ports serving the important overseas market of Quebec.

19 Of all the wants of the inhabitants of Quebec City, one that required particular catering to was the demand for French wines and brandies which, despite their high price owing to import duty, were considered indispensable.23 The town served as the capital of New France and as an administrative centre for the military and the clergy; it was also the terminus for seafaring ships. Its motley inhabitants, who grew in number from roughly 600 in 1650 to about 9,000 by 1759, were drawn together by their joyous pursuit of heavy drinking, a social ritual that, according to a 1744 census of trades, helped to keep 39 tavern keepers employed.24 In the narrow streets around Place Royale business in taverns flourished and bottles must have changed hands frequently.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6 Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7Flower-Pot Bottle

20 From at least 1730 onwards the bottle most prevalent in the households, shops, taverns, and warehouses of Quebec City was one that resembled the modern Benedictine bottle. Researchers have found examples of this type, like those in figures 6 and 7, at every exploration at Place Royale. Surprisingly, some bottles were found corked and still full although their liquid contents had turned rancid.

21 The bodies of these bottles were probably shaped at first by rolling on a marver (a polished metal or stone slab) and later by blowing in a tapered dip mould, which facilitated rapid production. Because they are generally wider at the shoulder than at the base, their form has been likened to that of the standard earthenware flower pot, hence the appellation flower-pot bottle.

22 The evidence — documentary, pictorial, and archaeological — points conclusively to France as the maker of those bottles. Volumes published in 1765 and 1772 as part of Diderot's Encyclopédie contain text and a series of illustrations on the making of flower-pot bottles in coal-fueled factories in France. Also the bottles figure prominently in many French paintings, drawings, and prints of the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century. For example, Chardin's painting La pourvoyeuse (1738; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) shows two bottles similar to the one in figure 7.26 But the most concrete testimony is provided by the innumerable bits and pieces of flower-pot bottles found littering French sites in Canada that date between 1730 and 1760.27

23 Besides its distinctive body shape the flower-pot bottle displays several other noteworthy features. Its string-rim, which lies less than a centimetre below the mouth, is especially striking, consisting of a thick cord of glass crudely applied and seldom tooled. Despite some marked variations the shoulder angle is generally weak and slopes gently as it merges with the neck which continues to taper inwards as it rises. The base is fairly uniform; it has a deep, well-formed, conical kick-up combined with a small scar from either a glass-tipped pontil or a blowpipe used as a pontil.28 The bottle glass itself ranges in colour from light olive green to deep brownish green and often has locked within it constellations of minute air bubbles. The average flower-pot bottle found in Canada is probably about 25 centimetres in height and holds about 0.9 litres (see footnote 38).

24 In order to discourage fraud caused by the fact that the standard used to measure capacity varied from place to place within France, the French government took steps to regulate the capacity of wine bottles. In 1735 Louis XV decreed that all bottles made or sold in France had to conform to the Parisian standard of measurement (the Parisian pinte equalled 0.93 litre).29 One result of this action would have been to encourage those shops that did not already use body moulds to adopt them. The state did little, however, to enforce the proclamation and differences in bottle size persisted.

25 One flower-pot bottle found at Place Royale (catalogue no. 1QU-2154(b)-IL2-434) bears a circular glass seal on its shoulder embossed with "A," an inscription that has yet to be deciphered. It was a popular practice among the more affluent in the eighteenth century to order their own bottles affixed with seals impressed with an identifying mark, such as one's name, initials, or amorial crest, a wine merchant's sign, or sometimes a date. In Sealed Bottles Sheelah Ruggles-Brise shows a French flower-pot bottle with a seal stamped "Toujours Ferme" and the arms of the Alsace family.30 However, the custom appears to have been followed less on the Continent than in England where sealed bottles were common. Certainly to find an eighteenth-century French sealed bottle in Canada is rare.

Blue Square Bottles

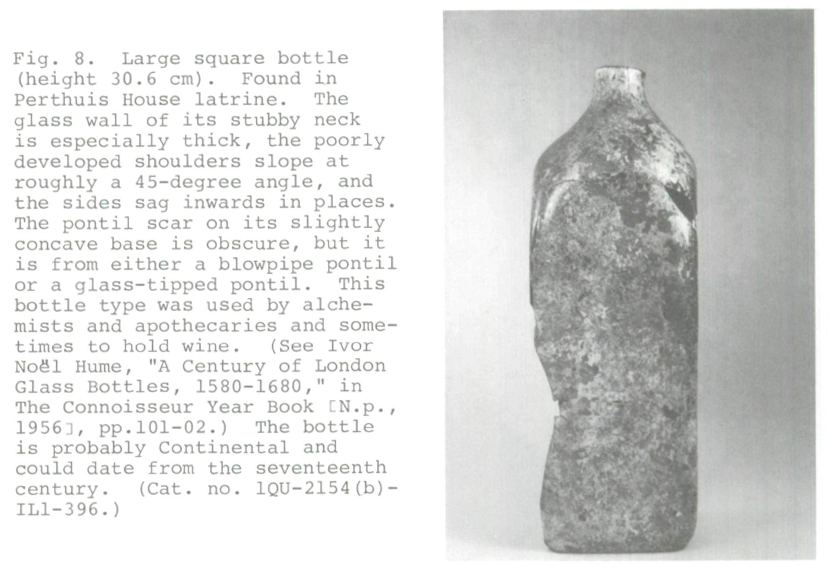

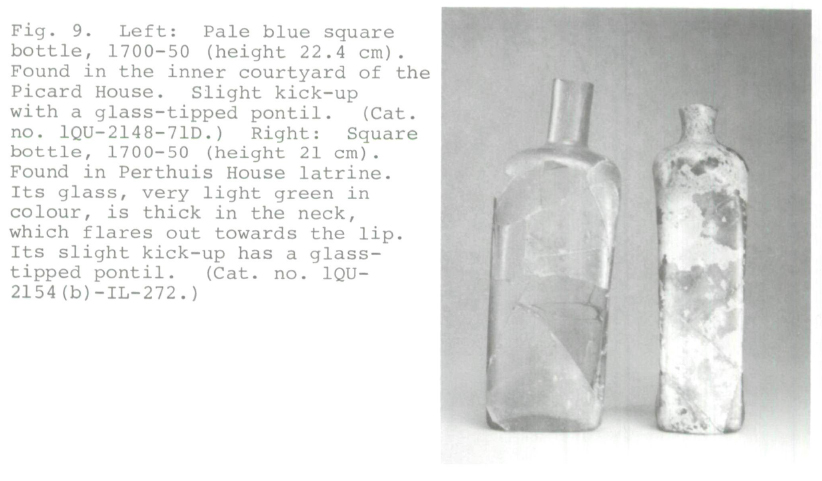

26 Next to the flower-pot bottle the type found most plentifully on French sites is the four-sided bottle, or case bottle as it became known because it was carried in partitioned boxes for protection.31 This form, which had a long history, came in various colours, sizes, and styles as indicated in figures 8 and 9. Square-sectioned bottles can be seen in two paintings by Jean-Baptiste Oudry — Le loup mort (1721; Wallace Collection, London) and Provisions de cuisine (ca. 1750; private collection, Neuilly-sur-Seine) — the second of which shows one aquamarine square bottle in addition to two flower-pot bottles.

27 Many of the square bottles found at Place Royale and at other French sites in contexts that date between 1720 and 1760 are pale blue in colour, like the one on the left in figure 9 and the one in Oudry's painting. These bottles, which range from 20 to 25 centimetres in height, were blown in rectangular dip moulds and have flat, vertical sides that meet to form rounded shoulders. Showing no signs of any finishing touches, the short, tubular necks are left without either a string-rim or a reinforcing collar around the lip. The bases are slightly concave and contain scars from either a blowpipe pontil or a glass-tipped pontil. The blue-tinted glass, often dotted with many entrapped tiny bubbles of air, is likely an example of the "common green" glass made in those French shops that continued to use wood-burning furnaces and to make bottles of a variety of shapes and uses, including medicine phials and square-bodied flasks.

28 Did the particular form of these bottles serve a specific purpose? One writer has called them "French toilet bottles." 32 Another has reasoned that because their necks lack string-rims the bottles were probably used to hold distilled spirits such as brandy or gin which, unlike effervescent wines and ales, did not need the cork-stopper tied down.33 And still another has added that the horizontal shoulder and narrow neck suggest that the bottles held a liquid of low viscosity such as liquor.34 The intended contents of these blue, square bottles remain a subject of speculation.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8 Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 929 It is known, though, that in the eighteenth century merchants used bottles to ship a multiplicity of liquids and even solids. Consider the following excerpts from a 1773 paper entitled "General Observations on the Commerce of Marseille:"

30 Regardless of their original contents the bottles, once emptied, were often put to sundry secondary uses. The colonists kept bottles in their homes for use as all-purpose containers, as indicated by the bottles and flasks listed in the inventory of household goods drawn up in 1732 on the death of Nicholas Jeremy, a Place Royale shopkeeper.36 They likely found empty wine bottles handy containers for the locally-brewed beer. And some, no doubt, used bottles as articles of trade with the Indians, specifically in association with the infamous brandy trade.37

31 A more complete understanding of the production, forms, and uses of early French bottles will emerge as the archaeological study of Place Royale and of other French sites in Canada progresses. This work could turn up the added specimens and facts needed to solve the mysteries of the bottles of Place Royale.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10