Reviews / Comptes rendus

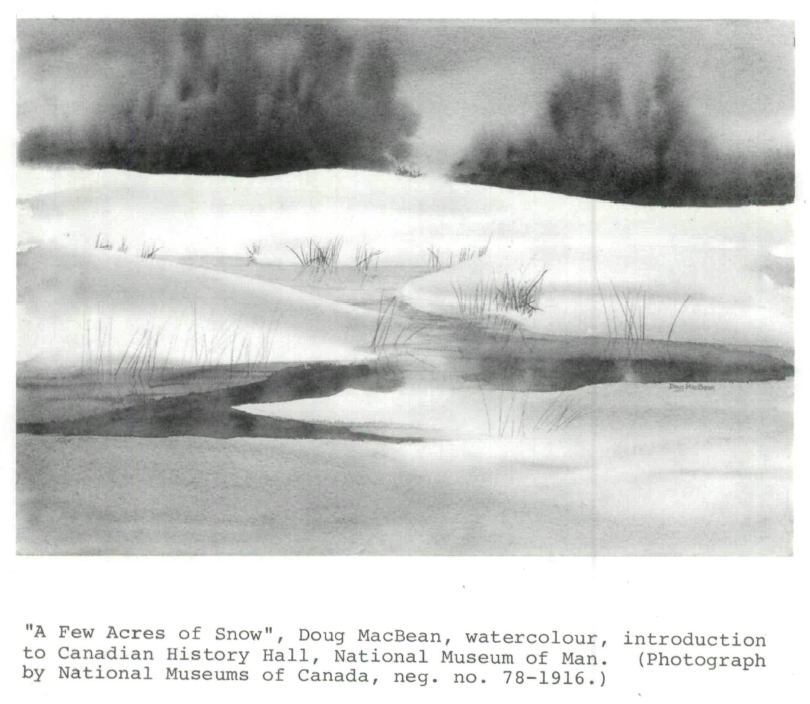

National Museum of Man, "A Few Acres of Snow/Quelques arpents de neige".

1 At first glance "A Few Acres of Snow" seems a wry and self-deprecating approach to the first permanent exhibit of Canada's national history. From a federal institution at the height of a national unity crisis we might be forgiven for expecting to find our traditional childhood companions — Responsible Government, the National Policy, the Undefended Border, and the Fathers of Confederation. Yet what the National Museum of Man has offered us in October 1977 is a far cry from the standard textbook versions of Canadian history, one which may startle the casual visitor, delight the enthusiastic historian, and perhaps bewilder the foreign guest.

2 To attempt to depict the history of an entire nation is a very large task and one rarely undertaken. Older nations, for example, Great Britain or Austria, are served by excellent City Museums such as those in London and Vienna and make no formal attempt to display national history. The Smithsonian Institution has tended to rely on symbols such as the American flag, the Model T, political campaigns, and inaugural gowns to carry the story, an approach which is feasible in a country where a more standardized education system and an easy acceptance of the overt displays of patriotism have made such symbols universally understood and accepted. The common identification of America with progress is well illustrated in Washington, though the virtual elimination of unpleasant themes such as slavery seems hardly credible for the 1960s when planning and construction were completed.

3 There were, it seems, few models for Canada to look to in 1970 when plans for a permanent exhibit were begun. It was thus an ambitious undertaking, with few precedents elsewhere, for the museum's relatively new (1964) History Division whose collection was grotesquely inadequate and whose experience was limited to a few relatively small travelling exhibits and one solid but celebratory show for Centennial.

4 In this context the deliberate decision to avoid the tyranny of chronology was daring, and the choice of themes — resources, rural life, urban life, social groups, and identities — was also a departure from historians' concerns of the late 1960s. The effect of the thematic approach has been to elevate the intellectual level of the exhibit higher than the national advertiser's grade six norm and to make secondary school knowledge of Canada's history and geography a district advantage in viewing the exhibit. The nature of the themes chosen and the attempt to include all regions in the survey make this an exhibit where there is something — an occupation, an experience, or a place — for all to identify with, a place for all "roots." The greatest strength of the History Hall is that it has succeeded in giving Canada, in its first permanent national exhibit, a history of the common people.

5 Happily this is not just a "folk life" look at everyday life, nor a glorification of past struggles and present success, but a critical and at times illuminating view of the societies and environment which our predecessors created. The first thematic area, "Environment and Man," reminds us with both explicit labels and implicit displays of the similarity of economic experience of the various regions. The bringing together of the artifacts of fish, timber, fur, and minerals illustrates the now commonly accepted view of the staple theory of Canada's economic development. Rather than extolling the intrinsic virtues of technological progress, an approach to which this topic so frequently lends itself, "Environment and Man" focuses on the voyageur and the miner, thereby emphasizing the conditions of work. Although admirable, this approach has left little room to discuss the political implications of this hinterland economy. The apparent determination to steer clear of political and external relations is least appropriate here and an opportunity is lost to illustrate the historical depth of the continuing Canadian economic crisis. The relationship between this first area and others in the exhibit seems weak; the various connections between the capital formation demonstrated here and the emergence of elites shown in later parts of the exhibit are not made, either symbolically or explicitly.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 In "Rural Life," the second area, there is a welcome, deliberate attempt to move away from an individualistic interpretation — the bold pioneer of yore — and to give more emphasis to community aspects of settlements and to the co-operative movements and corporate interests which have come to play an important role in the agricultural development of Canada. The theme of the capriciousness of rural life is boldly underlined by a giant roulette wheel, which, as Her Majesty found at the official opening, offers slight (and one would suggest statistically unsubstantiated) chance of success in Canada. Failure looms large in this unconventional interpretation, symbolized by the memorable prairie depression kitchen, a sparse, harsh evocation of the dashed hopes of a generation.

7 The weaknesses of this area reflect the huge gaps in the academic literature of rural life and agricultural history. The emphasis rests on the Anglo-French experience rather than on the more peculiar ethnic settlements of western Canada, and on the family farms of the prairies and Ontario to the detriment of subsistence farmers and ranchers. The role of agriculture as a dominant cultural ethos of the nineteenth century and its importance as the route to civilization for native peoples might also have been worthy of mention. It is perhaps too easy to present a shopping list of missing topics for there are obviously severe limitations imposed by the space available. It may be worth noting, however, that "Rural Life," with the very notable exception of the kitchen, seems less well served by its designer than other areas. Two-thirds of the exhibit appears to be wall-hung glass cases or simply hung photographs. A central open space occupied by a garish and isolated tractor serves little purpose in visitor flow, while a small and unimpressive model farm occupies space which might have been better used to offer interpretations of the rural tavern in Upper Canada, the travelling preacher in the west, or the rural press.

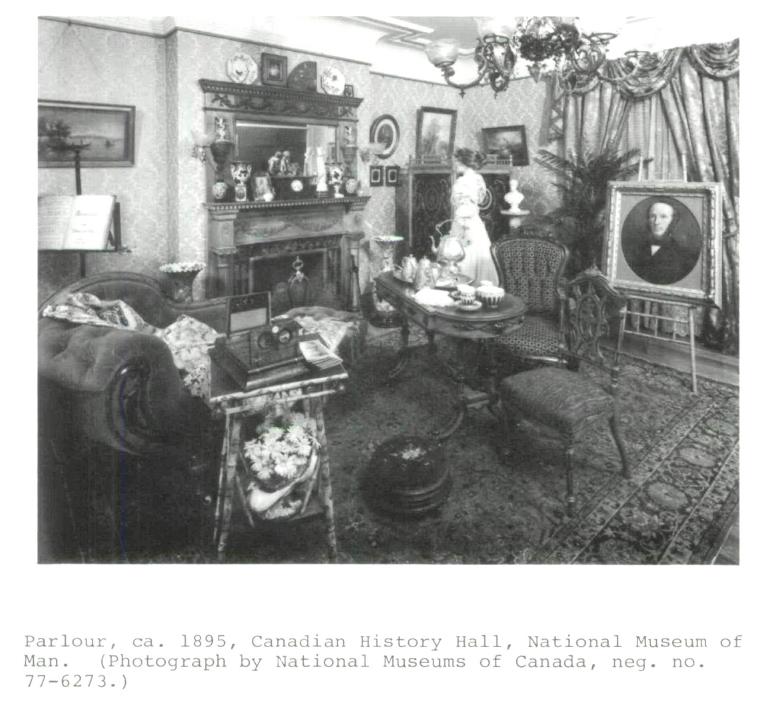

8 One of the more well-developed aspects, both in theory and in case studies, of the "new" Canadian history is urban history, an area of study which the History Division itself has furthered through its Urban History Review and the new Biography of Canadian Cities. "The Urban Environment" area of the exhibit reflects this impressive literature. The unifying theme of the role of transportation in altering the face of urban Canada is one which responds well to interpretation by artifact, map, slide, and period setting. Indeed, all of these are used in the urban gallery, producing a perhaps intentional atmosphere of bustle and activity. From the point of view of a museum professional, the section which depicts, in connecting segments, the transformation of furniture-making from the craftsman to the industrial manufacturer is one of the most instructive. The designer and historian have here produced a model historical exhibit. This section itself illustrates most of the themes of the urban hall: the change from individual to mass production, the role of transport changes in providing an effective urban work force, and the changes in social relationships as the workshop is replaced by the factory and the owner/craftsman by the foreman and manager. Almost incidentally do we also learn of the stages of production of furniture and of the attempt to cater to the increasingly uniform tastes and habits of a growing urban population. By framing these illustrations within the context of the changing work place we are again reminded of the hall's overall approach — the history of the common people of Canada.

9 The urban area is less successful in its treatment of society. The odd cane and feather boa are almost clichés and seem the afterthought of an anxious curator attempting to "lighten" a heavily academic exhibit. One looks in vain, too, for any discussion of urban architecture, which would portray the most familiar artifacts of all for most visitors. Perhaps this can be added to the already well developed and informative slide presentation offered in a small viewing area. This intimate space is one of the few flexible sections in the entire History Hall and might also be adapted for use for a small class, demonstration, or temporary exhibit. As prospects for a new museum building diminish, the History Division might well regret the lack of more flexible space in other areas.

10 The fourth area deals with Canadian "Social Groups", a rather mealy-mouthed euphemism for class, still apparently an unpleasant word for the general public. The focal point here, not unexpectedly, is the bourgeois parlour, a production which several museums and historic houses and villages across the country have tried with varying degrees of success. From a curator's standpoint a parlour has many advantages. Here is the chance to display all the late Victorian and Edwardian furnishings with which so many museums are amply endowed. It usually produces a memorable spectacle because of its stark contrast with restrained contemporary interiors. For younger visitors it can induce a fashionable nostalgia; for older visitors the charm is for the familiar (of the "well, Aunt Harriet still has a table just like that" variety, so well known to curators) elevated to history. The parlour here fulfills all such expectations. The stuff of which Notman's photographs are made, it creates a comfortable balance of complacency, order, and vulgar provincial display. One might prefer dimmer or even natural lighting at the expense of losing sight of some artifacts — for the success of a period room lies not in the individual pieces, attractive as they may be, but in the sum of the whole.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 211 More significant perhaps is the didactic use made of this display, to emphasize in labels and by juxtaposition that such wealth existed in close proximity to and, indeed, perhaps because of the widespread poverty particularly evident in urban areas at the turn of the century. The parlour is directly related to an exhibit on living condition of the urban poor and on the early struggles of reformers and trade unions for shorter hours and a better wage. Much of this material will be new to present-day high school students and even "Ginger" Goodwin, a trade unionist shot by police and one of the few names to appear in the entire history Hall, is hardly a household word outside the charmed circle of British Columbia's labour historians.

12 Perhaps it is harsh to suggest that the national exhibit speaks of class in less than muted tones, for the exhibit is to be highly commended for offering a view of Canada markedly different from all the Centennial celebrations with which our museums are burdened. Maturity and self-confidence are reflected in a national museum which suggests that our past is not all a Hollywood epic of expansive liberal individualism, but is one which has involved clashes of interest groups and poverty and disillusionment for a great many.

13 A small theatre provides a resting place for an average classroom group as visitors move from "Social Groups" to "Canadian Identities." Alas, the period charm of a CPR waiting room would have been preferable to sitting through the specially produced film shown here. it is an unmitigated disaster, fifteen minutes long, which attempts to show through mime (and a lot of NFB bleeps) that Canadians act like robots and can be reproduced by a Xerox machine. It is badly acted and crudely filmed, offers the ideology of a bent mind, and is the direct antithesis of all that has been said of the common people through the exhibit. Let us hope that it was not too costly a mistake and pray that it will be removed soon.

14 Even the opening theme of "Canadian Identities" seems to contradict the film by showing a profusion of handcrafted artifacts to represent the diversity and individuality of some aspects of Canadian society. Indeed, the visitor might be forgiven for thinking that he had arrived in the hall of folk culture, for much of this area seems closer in approach to folklore than to history and as a gallery it seems somewhat unrelated to other areas of the History Hall. Some of the more intrinsically interesting and attractive artifacts are here although French-Canadians might be amused to see themselves in Gitanes and disques. However, the themes of the separateness of Quebec, the geographical barriers to unity, and the British pressures on the mosaic of other cultures and languages, are worth pursuing further and it might well be to this area that the division will turn its attention when funds for expanding the exhibit become available. At the moment it is not the strong conclusion to the History Hall that one would like to see. If such a reworking were possible, the theme of winter as a common historical and contemporary experience for most Canadians, a theme which is only sketched here, could be pursued in greater depth. It offers the potential for light, if not comic, relief, that element of entertainment of which all museums must be conscious and one to which the director of the National Museum of Man has always paid eloquent lip service. This area offers a further challenge to the designer for it is the one space which can be viewed from above, an elevation which ought to be used to advantage.

15 On the whole, display techniques throughout the History Hall are competent, varied, and well researched, but with the exception of the immigrant's roulette wheel offer nothing novel to the Canadian museum world. Apart from some confusion at the entrance, which is duplicated to provide access from both stairways, and some congestion at the beginning of the first area where traffic is squeezed through two successive narrow openings, the visitor flow on a busy Sunday afternoon was adequate. Artifacts in general are used to illustrate an idea rather than for their own sake. Though this may reflect the nature of the collections policy there are claims to be made for the memorable image left by isolating and focusing on one special object. The stunning effect of such an approach in the museum's Archaeology and West Coast Indian Halls would have been well worth repeating in small measure. As it is, neither the entering nor the leaving of the History Hall is dramatic, and those familiar with the entrances to museums in Victoria or Winnipeg or who have seen the Model T and Old Glory which symbolize America at the Smithsonian might well be surprised at the mildly sardonic nature of the gentle landscape of "A Few Acres of Snow" which opens Canada's national exhibit.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 316 Though its trumpet is muted, the National Museum of Man's History Hall fills most of the criteria for a successful exhibit. With its emphasis on the experience of the common people in all regions, it offers a story in which most Canadians can find their relevant place. It presents a new and critical approach and thus will have an impact on one's view of this country. And even though it has limited opportunity for flexible temporary supplements, I would return. In particular I would take my visiting cousins to the prairie kitchen, for this is the image that remained longest with me. Perhaps this is because of my own affection for the prairies, but it is also to pay tribute to a designer and a curator who knew when to stop — an often unused talent in museums. This derelict prairie farm kitchen of the 1930s, with its worn linoleum floor, minimal furniture, peeling walls, and desolate calendar on the wall, conveys a clear and direct historical message. The contrast with the bourgeois parlour jumps quickly to mind, as does our dependence on the wise harvesting of our resources. It reflects our naive enthusiasm that the twentieth century belonged to us as we rushed to expand the nation, and it reminds us of the recurring economic crises which have been a factor in swelling the population of our cities. But more than this, its very barrenness conveys a powerful emotion, and as the dust and sand swirl around the floor the prairie romantic could be forgiven for believing that the last dungareed child had just closed the swinging door.

Department of History

University of Manitoba

17 The permanent history hall of the National Museum of Man may be said to have evolved from outlines discussed in 1964-65 when the permanent exhibitions for a new national museum building were being planned — "evolved," yes, but much changed from those earlier plans which had to be shelved when the new building was cancelled. In 1970 the museum's historians began discussing concepts and making recommendations regarding the approach to be taken to the history of Canada in the renovated Victoria Memorial Museum Building where 8,000 square feet on the fourth floor was reserved for the history hall.

18 An area of that size is hardly excessive for portraying the whole sweep of Canadian history. Obviously we had to be highly selective, yet pan-Canadian in scope. Everyone agreed that the emphasis should be on social history, which the museum was best equipped to illustrate and which offered the greatest opportunity for innovation and creativity. Everyone agreed, also, that this meant de-emphasizing the traditional interpretation: chronicles of great events; explorers, soldiers, and statesmen; responsible government, Confederation, and the broadening-out of British-Canadian and French-Canadian custom from precedent even unto precendent. Since the raw material of social history is regional, even local, this could have led to a series of regional treatments by chronological period. Might that not have accentuated what has divided Canadians rather than what they have experienced in common? Consequently, we selected a thematic approach which looked for common threads without attempting to mask unmistakable differences. Our themes would be both all-encompassing and capable of being illustrated from various regional and chronological examples. It was in the choice of these examples that the relative comprehensiveness of the exhibition would be put to the test.

19 The opening theme seeks to show how people have coped historically with the environment as well as to show how primary resource industries — fishery, fur trade, timber trade, and mining — have affected Canadians and their environment. Examples are taken from the Atlantic fishery down to the nineteenth century, from Quebec and the western fur trade, from the nineteenth- and twentieth-century forest industries of Quebec and British Columbia, and from the Cape Breton coal mines of the 1920s. The old society that agriculture created is the subject of the second theme, with examples from Quebec, Ontario, and the Prairies from the 1700s to the 1900s. Here the emphasis is less on technological change than on political and economic effects: the decline of the family farm, the rise of agribusiness, and the encroachment of urbanization. The third theme, urban development, follows naturally, yet demonstrates that Canadian towns often had beginnings independent of agriculture — as bases for resource exploitation and military activity as well as market towns and cultural centres. The sweep of urban chronology is depicted audio-visually while the artifacts and graphics concentrate on town plans, the world of work, and transportation with examples from several Canadian cities. The fourth theme attempts to depict social groupings and social change, to contrast wealth and poverty, privilege and deprivation, and to present the origins of trade unionism. Examples include Upper Canada and Vancouver Island and cover the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The fifth and final theme seeks to reflect the wide variety of Canadian experiences and attitudes down to the present day as illustrated by a broad cross-section of the country.

20 The selection of artifacts and graphics was made to fit these preconceived themes and it was, admittedly, difficult. One cannot create an exhibit in the abstract without paying the price of delay and often serious compromise. The artifacts should be selected as early as possible in the design process in order to minimize crises too close to opening day. Yet I would never subscribe to an interpretive historical exhibition in which the artifacts chosen would dictate the historical themes to be depicted. The artifacts may modify the themes but not control them since this could result in an extremely limited exhibit. The historical questions we wish to answer by means of artifacts and graphics must be decided in advance, otherwise how do we know whether we have looked for all the materials that might exist?

21 In retrospect, should we have done differently? By and large, I think not. Areas four and five might be reconsidered and we might have profited from more period rooms: in my opinion the parlour, furniture shop and factory, kitchen, coal mine, and immigrant ship are the most successful parts of the exhibition because they place artifacts in a context that the general public, as distinct from the buffs and the cognoscenti, can appreciate. From time to time museums may indulge in the luxury of serving particular interest groups but, since most museums are supported by the public at large, they must try to reach that public. Showing everyday objects as they were used, in their normal relationship to one another, is one of the best methods of doing so, and it obviates a great deal of verbal explanation.

Chief

History Division

National Museum of Man