Articles

Civic Ornaments:

Ironwork in Halifax Parks

A la fin du XIXe siècle, plusieurs pièces décoratives en fer forgé - pavillons, portes, fontaines - furent érigées dans les deux grands parcs de halifax, les Public Gardens et le Point Pleasant Park, en l'honneur des donateurs ou pour marquer des événements importants de l'époque. Ces "décoration municipales", achetées avec des fonds donnés par des particuliers au réunis lors de collectes de fonds publiques, étaient pour la plupart fabriqués par la MacFarlane Company, de Glasgow en Ecosse, bien qu'une de ces pièces ait été réalisée en Nouvelle-Ecosse et une autre, à New York. Ces structures illustrent aussi bien la variété et la popularité des décoration de ferronerie à l'époque que l'intérêt manifesté par les Haligoniens pour l'embellissement et la mise en valeur de leurs parcs.

1 Halifax's two major parks, the Public Gardens and Point Pleasant Park,1 contain several pieces of decorative ironwork, including pavilions, gates, and fountains, which date from the end of the nineteenth century and most of which were made in Great Britain or the United States. They are examples of the popularity and availability of iron ornaments and of Haligonians interest in beautifying and improving their parks. Preliminary research reveals something of how, why, and where these objects were acquired.

2 In 1881 a Halifax merchant, William P. West, left a legacy of $5,000 "to be expended in improving the grounds of Point Pleasant Park."2 Part of this fund went to the purchase of two cast iron pavilions or summer houses from Walter Macfarlane and Company, Saracen Foundry of Glasgow, Scotland. One was erected facing the harbour, the other facing out to sea (fig. 1). The Annual Report of the city for 1884-85 stated that the pavilions "greatly add to the beauty of the localities where they are placed, besides affording shade and rest to those who frequent these delightful spots."3

3 At the end of the nineteenth century Nova Scotia had numerous iron foundries which produced castings for the shipbuilding, lumbering, mining, and agricultural industries. The foundries' production of decorative pieces was limited to fences and some architectural ironwork and the patterns for most of these may have been imported. Therefore it is not surprising that the pavilions were purchased not from a local firm but from Macfarlane, one of the period's foremost producers of decorative cast iron. Macfarlane products were advertised in Nova Scotia and were exported as far away as India and Australia. Access to one of the company's extensive catalogues may have guided the park directors in their decision to purchase the pavilions.

Display large image of Figure 1

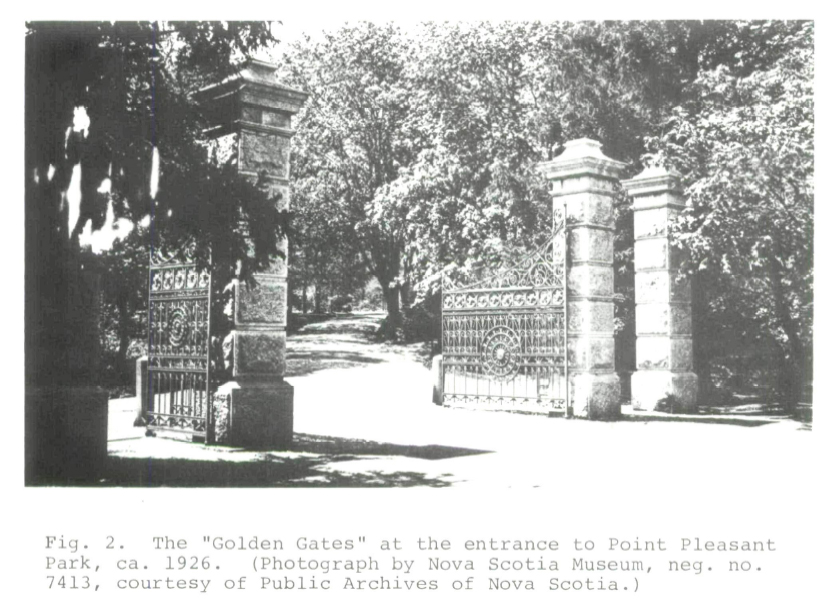

Display large image of Figure 14 The other major piece of ironwork in Point Pleasant Park is a set of gates, presented by Chief Justice Sir William Young in 1886 (fig. 2). Young had been instrumental in obtaining the park lands from the imperial authorities and served as one of the park directors. He first thought of presenting the gates about 1884, but at that time a new entrance road to the park was unfinished. Because the road work was progressing slowly and because he was "getting up in years," Young lent the city $1,500 to complete the job so his gates could be erected.4 This decisive action was timely as he died eight months after their installation.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 25 The design of the gates was chosen in an informal competition. Young and E.H. Keating, the city engineer, "looked through designs and selected some patterns after the style [they] wanted and then invited tenders."5 The designs could have been from a Macfarlane catalogue since a letter from that firm to Keating indicates that he had requested information on a specific gate for the competition and that he had quoted a stock number.6 Designs were also sought from the Starr Manufacturing Company of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, from an unidentified Ontario foundry, and possibly from other Scottish ironworks. The half-dozen designs received were inspected by Young and a few of his friends, Keating, the Mayor, several aldermen, and representatives of the Royal Engineers. This group selected the Starr proposal, designed by local architect Edward Elliot, as "considerably the finest."7

6 The cost of the gates is not known, although Young was prepared to pay as much as $500. Made principally of wrought iron, the gates hand on posts of Nova Scotia granite and have been gilded, hence the name the "Golden Gates." They have always served as simply an ornamental entrance since there has never been a fence around the park. At the time Heating's own opinion was that "an arch or something of that sort would answer the purpose of an ornamental entrance better."8 The Starr Manufacturing Company, best known for its patented spring skates, does not appear to have produced other decorative pieces of the same scale as the gates.

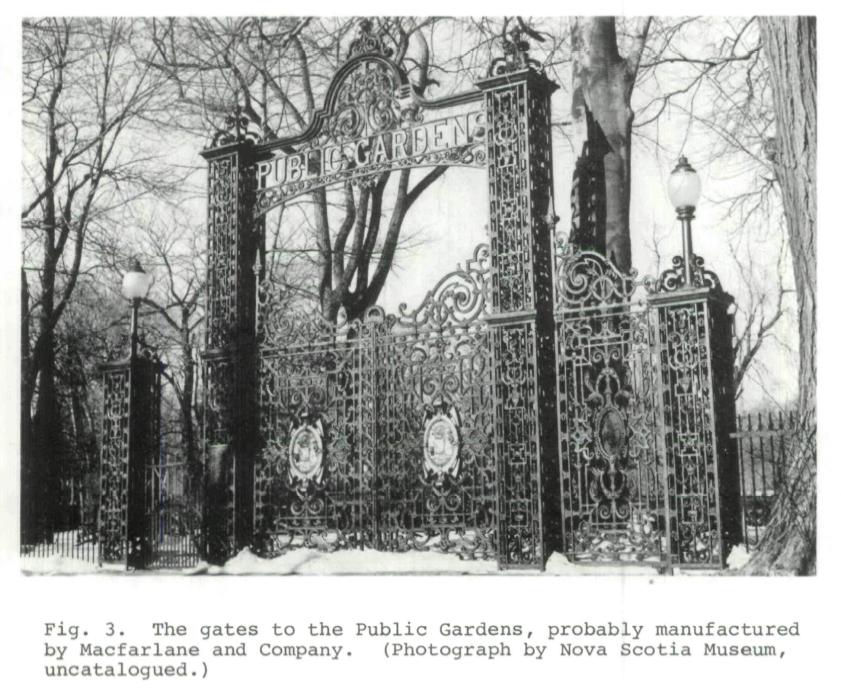

7 Another set of gates was purchased in 1890, on this occasion for the Public Gardens, and installed in a large, wooden gatehouse which contained a committee room, office, women's water closet, and canteen. Macfarlane was probably awarded this contract as the gates are almost identical to a design shown in one of the company's catalogues. In any case the company seems to have submitted a drawing and a cost estimate since the Commons Committee's minutes for 21 August 1896 state that "It was decided to order gates for entrance building from Glasgow as per plan shown by chairman at a cost of about $600."9 Part of this money came from a fund raised by a women's group to commemorate local volunteers who had fought in the North-West Rebellion. The gates were re-erected in a new location in 1907 when an iron fence was put around the gardens. At that time they were hung on a set of cast iron piers with "Public Gardens" cast in an arch over them (fig. 3).

Display large image of Figure 3

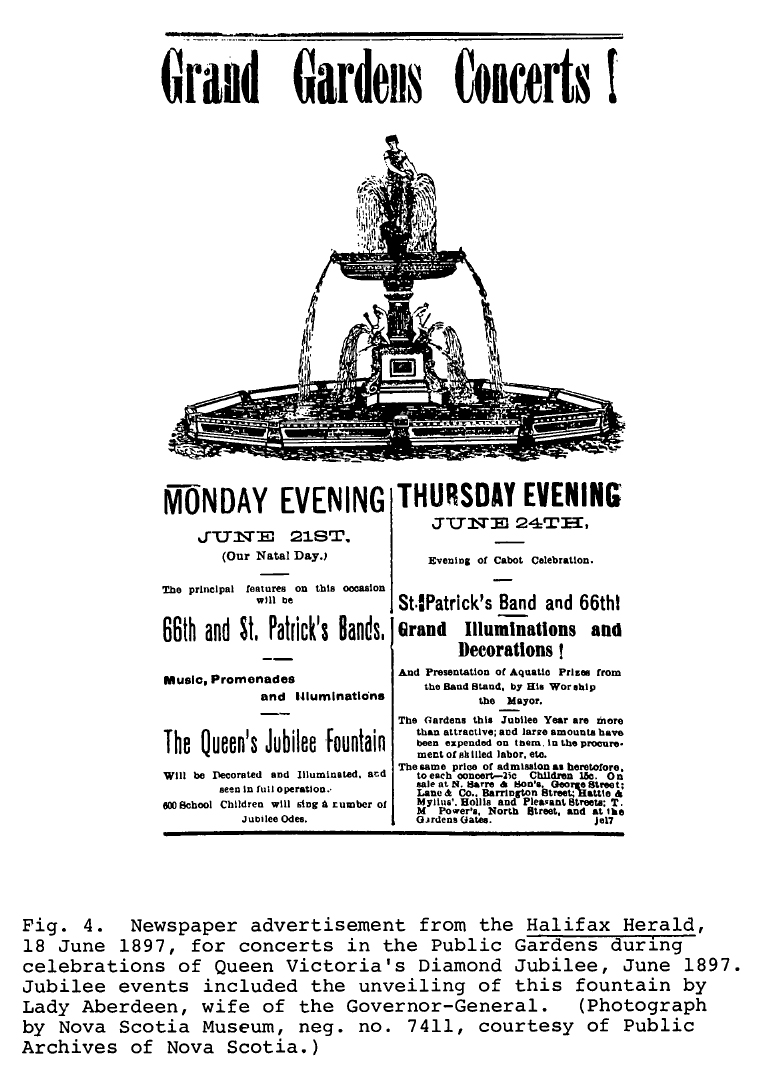

Display large image of Figure 38 The next iron ornament in the Public Gardens was a fountain erected as a tribute to Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897 (fig. 4). Its unveiling by Lady Aberdeen, with the assistance of her husband the Governor-General, was the occasion for an impressive ceremony attended by a large number of Haligonians, a group of Micmacs in native dress, the Halifax Academy fife and drum band, and a choir of 600 schoolchildren. The choir sang a patriotic song, "Victoria," as the covering was removed from the fountain and the silver-plated tap turned to start the sprays.10

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 69 Perhaps the only inappropriate aspect of the event was that the fountain in honour of Queen Victoria was cast in the United States; however, the Canadian government had waived the import duty and thus saved the committee $300. The responsibility of gathering suitable designs had been given to the chairman of the Commons Committee who "was about to visit the United States [and] was requested to make enquiries as to design, cost, fee and report the same to the commissioners on his return."11 On 14 April 1897 designs were submitted and that of the J.W. Fiske Foundry of New York, a firm specializing in decorative ironwork, was selected. Much of the cost of the fountain, $1,700 plus shipping charges, was raised through admissions to band concerts.

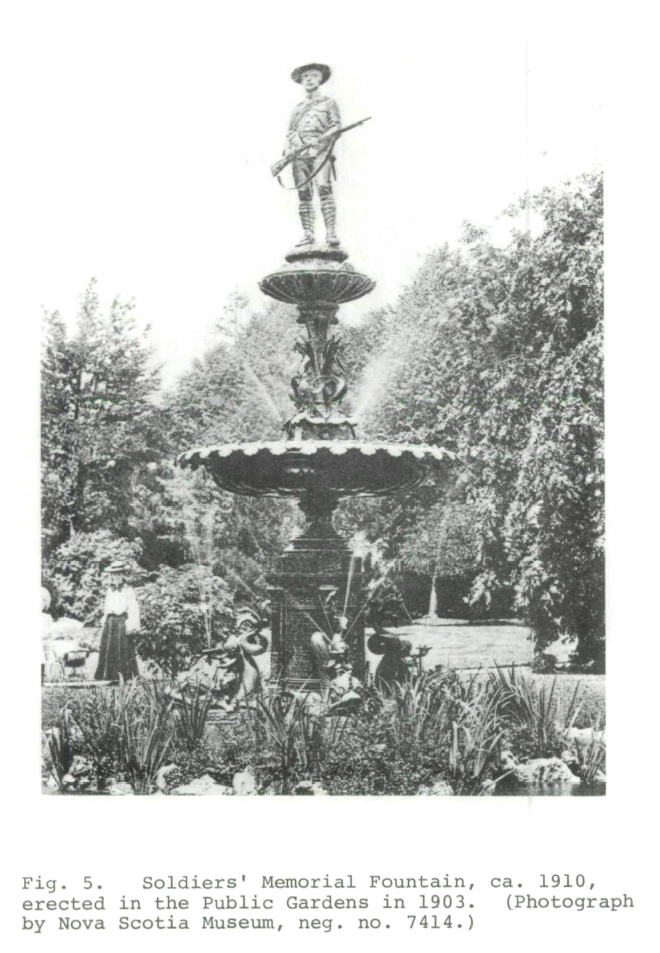

10 The last major piece of ironwork in the Public Gardens was another memorial fountain, this time "in commemoration of the service of our citizen soldiers in the South African Campaign" (fig. 5). Although the Commons Committee decided in 1900 to purchase a fountain and later allocated money from concert admissions to pay for it,12 committee changes and other undetermined problems delayed the installation until 1903. The committee again purchased from Macfarlane, choosing a stock design for the base (fig. 6) but requesting the substitution of a member of the Canadian Mounted Riflemen for the female figure. The committee minutes of 2 February 1903 report that they were shown "quite a number of photos for figure to surmount fountain... the ones in standing positions were selected." Tradition has it that a well-known local sportsman, Billy Pickering, served as the model. A Macfarlane catalogue of ca. 1908 shows a soldier figure, apparently identical to the Halifax example, and illustrates the use of the figure on a fountain. This suggests that the request from the Commons Committee may have encouraged the company to add this model to its line.

11 The ironwork structures described above were all erected under similar circumstances. All were memorials, either to donors or to significant events. More importantly, all were regarded, like the "Golden Gates,"13 as civic ornaments, improvements to their surroundings. It is also notable that they were purchased not with public funds but with private donations or with money raised through band concert admissions. Most striking was the important part played by Walter Macfarlane and Company which manufactured four of the structures (counting the two pavilions) and tendered for one other. The continued patronage of this company was probably due to the quality and variety of its merchandise and to its marketing initiatives outside Great Britain.

12 The pavilions and the two fountains bear foundry marks which helped in conclusively identifying their origins; contemporary accounts sometimes noted only that an item came from Glasgow or New York. Access to some Macfarlane catalogue illustrations further assisted in identifying pieces. As yet no catalogues or drawings, which would have been included with tenders, have been located in Halifax but these may eventually come to light in the city documents.

13 These ironwork ornaments exemplify the phenomenal popularity of iron in the nineteenth century. Iron, particularly cast iron, had an almost endless variety of uses from cradles to coffins to complete building façades. Such civic ornaments continue to give pleasure to passers-by and attest to the imagination and forethought of those responsible for their acquisition.