Articles

Christina Morris:

Micmac Artist and Artist's Model

1 A well-known citizen of ninteenth-century Halifax was the Micmac artist, Mali Christianne Paul Mollise (anglicized to "Christina Morris"). She did exquisite work in all the traditional Micmac crafts, but she contributed to Nova Scotian art in another way as well: at least seven portraits of her, by various artists, have survived.

2 Christina, the daughter of Hobblewest Paul of Stewiacke, was born ca. 1804 either at Stewiacke or at the Indian Reserve near Ship Harbour, N.S. When still very young she married Tom Mollise, a Micmac whose family traditionally camped on McNab's Island in Halifax Harbour. Her husband died shortly thereafter and although she never remarried she later adopted and raised a son, Joe.1 Not much is known of her early life except that she combined beauty with a reputation for virtue and piety, which could not have been easy for a Micmac woman living alone in the 1820s.

3 Christina would have known Joseph Howe, Commissioner of Indian Affairs and later Premier of Nova Scotia. Two mayors of Halifax were her personal friends, as was another Indian Commissioner, Col. William Chearnley. Christina was, unofficially, "quillworker to Her Majesty the Queen," having provided Victoria with examples of her work from time to time. 2 The City of Halifax even presented a portrait of her to the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII. After 1850 her history is surprisingly well-documented and it provides fascinating glimpses of Nova Scotia in the second half of the nineteenth century.

4 In 1854 she appears in the Provincial Exhibition Catalogue as "Christina Morris, residence Dartmouth, winner of the First Prize for best full-sized birchbark canoe and worked paddles." 3 She won second prize for a nest of six quilled boxes. Shortly afterward she moved to Chocolate Lake, on the Northwest Arm, Halifax. "At that lake she first camped on a grassy hill where an old powder magazine once was...later she had a little house, it was painted green and had shutters...."4 Both land and cottage were said to be a gift from Queen Victoria:

5 She was well-known to Nova Scotian artists as well. One could take a picnic out to the Arm, perhaps buy some of her beautifully-made quillwork, and spend a few hours painting, with a picturesquely-garbed Indian model:

6 A rival paper, the Halifax Evening Express, had this to say, "The Sun of this morning speaks in flattering terms of a likeness, painted by Mr. Gush, of that well-known squaw, Mrs. Christianne Morris...we do not agree with our contemporary as to the merits of the picture; in fact it is hard to recognize at all the feature of this good woman." 7This sounds a trifle exaggerated. However, William Gush generalized her costume; perhaps he romanticized her face as well.

Display large image of Figure 1

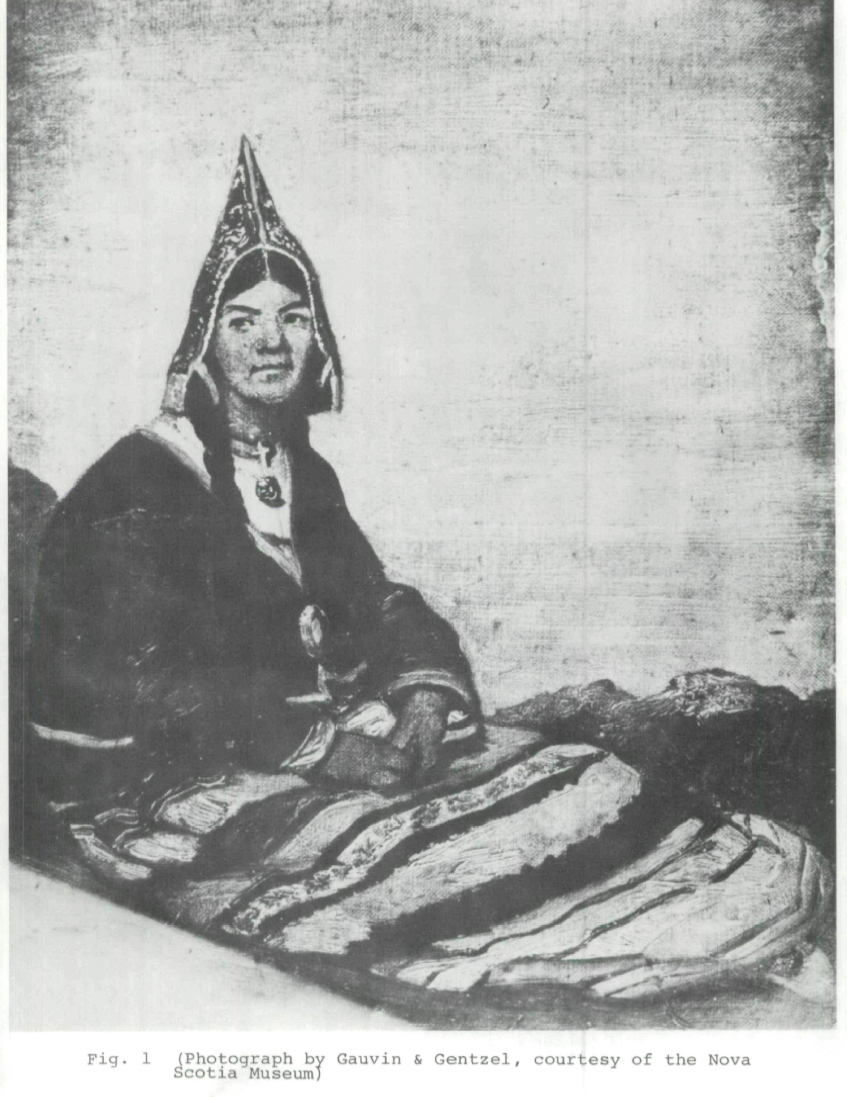

Display large image of Figure 17 According to H. Piers, an early curator of the Nova Scotia Museum, there were two copies of this painting. One of these was the work presented to the Prince of Wales on his visit to Halifax in 1860.8 The second became the property of Samuel R. Caldwell, Mayor of Halifax and a friend of the model. In 1918 Piers was able to examine this second copy, which had passed to Caldwell's nephew. It was an unsigned oil on canvas, 14.85 inches x 11.00 inches, with the back stretcher marked "Christina Morris". The model is seated on the ground, by what was assumed to be Chocolate Lake, the site of Mrs. Morris' "villa". The jacket was blue, trimmed with red; the skirt black with horizontal bands of red, yellow, black and white .9Piers had the painting photographed by Gauvin and Gentzel of Halifax; figure 1 is copied from this glass negative.

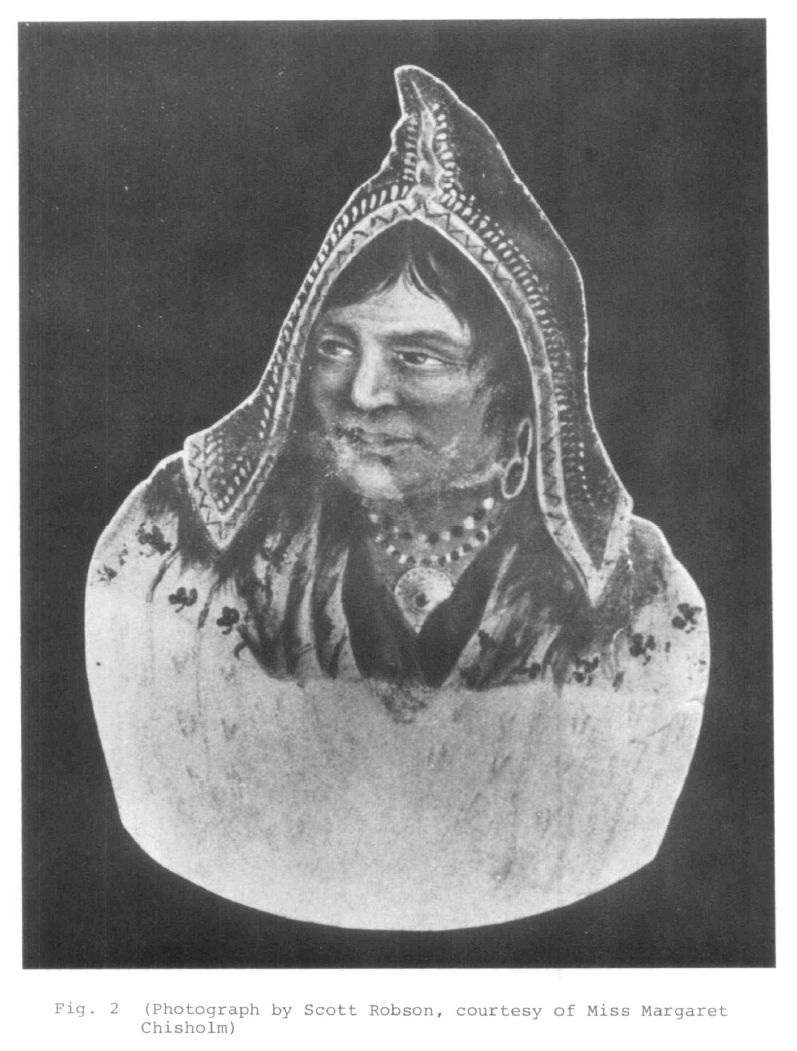

8 Piers added a postscript to his note on the Gush oil: "I think Mrs. Jas. T. Egan of Dutch Village, owns a miniature of Christina Morris by Valentine (?)."10 About 1920 the ceramic artist Alice Egan Hagen11 portrayed a Micmac woman on one of her bowls. Mrs. Hagen's daughter remembers that this painting was copied from a borrowed portrait labelled "Christy Ann" which the artist had obtained from her own mother, Mrs. T.J. Egan (the mother-in-law of Mrs. Jas. T. Egan). In 1931, when Mrs. T.J. Egan died, a cut-out watercolour of a Micmac woman's head and shoulders (fig. 2) was discovered inside the frame of a painting by William Valentine.12 This portrait reads "Christy Ann" in faded brown ink on the reverse. Beneath is pencilled "By W. Valentine" in a later hand. It seems probable that this is the work referred to by Piers. It matches the painting on Mrs. Hagen's bowl.13

9 Recent research has provided circumstantial evidence to identify three other portraits of Christina Morris. A pastel (fig. 3) from the New Brunswick Museum is identified only as "Micmac Women/Unknown Mid-19th-Century Artist". This is a beautiful work and the artist has faithfully reproduced every detail of the costume with its intricate ribbon appliqué and beadwork. This detail is invaluable in that no two such costumes were ever the same. Micmac women of the elaborate-applique period can be accurately identified in contemporary photographs by the design on their clothing and sometimes appear in the same dress over a period of forty years.14 With this in mind, look at the studio photograph (fig. 4) of the woman and boy. The costume details, particularly noticeable on the jacket edgings, are identical — line for line. The women's faces are similar, allowing for a greater age at the time of the photograph. For these reasons it is reasonable to say that the woman in the photograph was, earlier, the model for the pastel.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 410 The photograph was taken in Halifax by J.S. Rogers, ("The People's Gallery"), between 1863 and 1874, 15 years in which Christina Morris was well-known in Halifax, was winning Firsts in Provincial Exhibitions, and was accompanied everywhere by her young adopted son, Joe (the boy in the photo?). She was publicized as having posed for Gush, so perhaps it is not too far-fetched that the pastel's unknown artist and the photographer, wanting an Indian model, would have turned to her as well.16

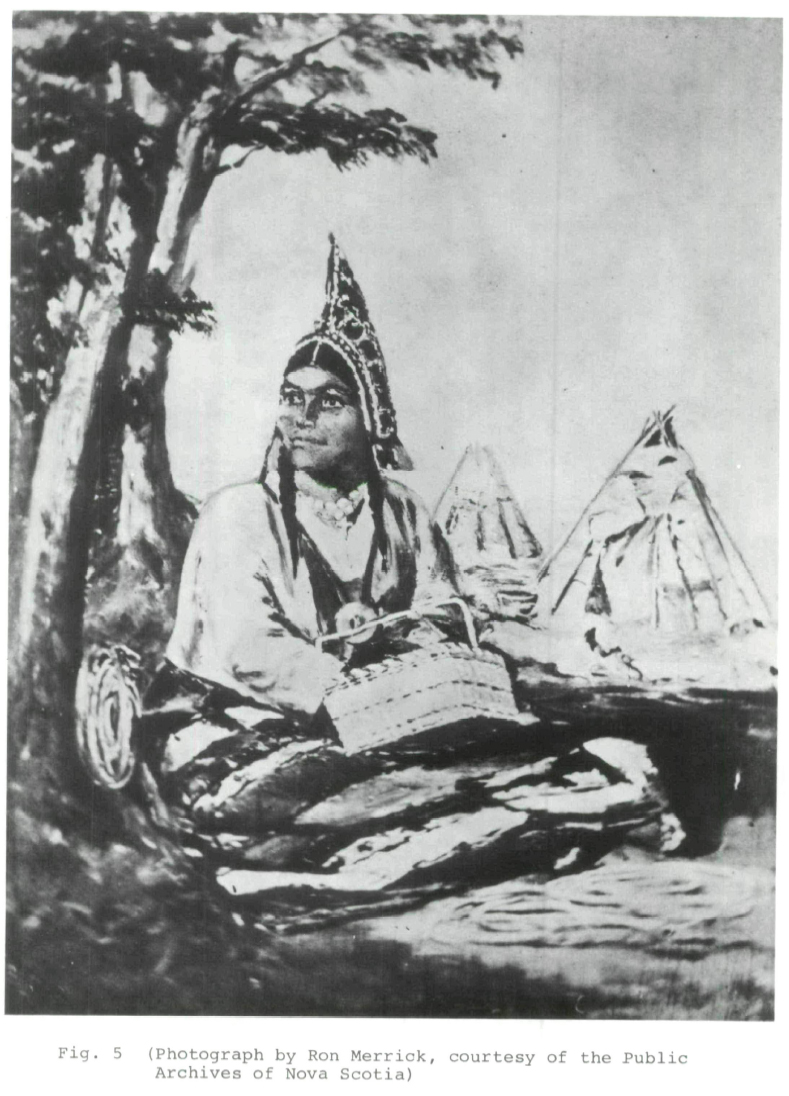

11 In the collection of the Public Archives df Nova Scotia is a photo of a drawing of a Micmac woman (fig. 5) attributed to Rebecca Crane Starr (1917-1902) of Halifax. The model is seated on the ground holding a basket. The pose is similar to the Gush oil (fig. 1), the skirt has the same type of banding, and the strong face resembles that in the Rogers photo (fig. 4). Again, the place and time suggest Christina Morris. On one corner of the photo is a pencilled "Christy Ann?", added many years ago by the Assistant Provincial Archivist, Phyllis Blakeley. She thinks it likely that the identification came from some of the older Micmacs who visited the Archives from time to time [Phyllis Blakeley, 1977: personal communication].

12 Christina would certainly have caught an artist's eye. Her native costume was evidently such a walking advertisement for exotic needlework that Indian Commissioner Col. William Chearnley, who was interested in Indian art, commissioned her to make two complete Micmac women's outfits — one for his collection, the other for his wife to wear to fancy-dress balls. For these he paid the then staggering sum of $300;17 they must have been magnificent. Another costume of Christina's making won First Prize in the Provincial Exhibition of 1854.18

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 613 Christina Morris was evidently an excellent artist in her own right. The Exhibition Catalogue for 1868 mentions her as "Christine Morris, residence North-west Arm; winner of the First Prize for best nest of six quilled boxes, best large and small (splint) baskets, and best covered clothes baskets."19 The Nova Scotia Museum has a pair of her snowshoes, made during this period for Mayor Caldwell's brother William, who was also a Mayor of Halifax. Piers judged them to be a marvel of the snowshoe-weaver's art with six to seven thongs to the inch, "very finely done" in caribou rawhide.20

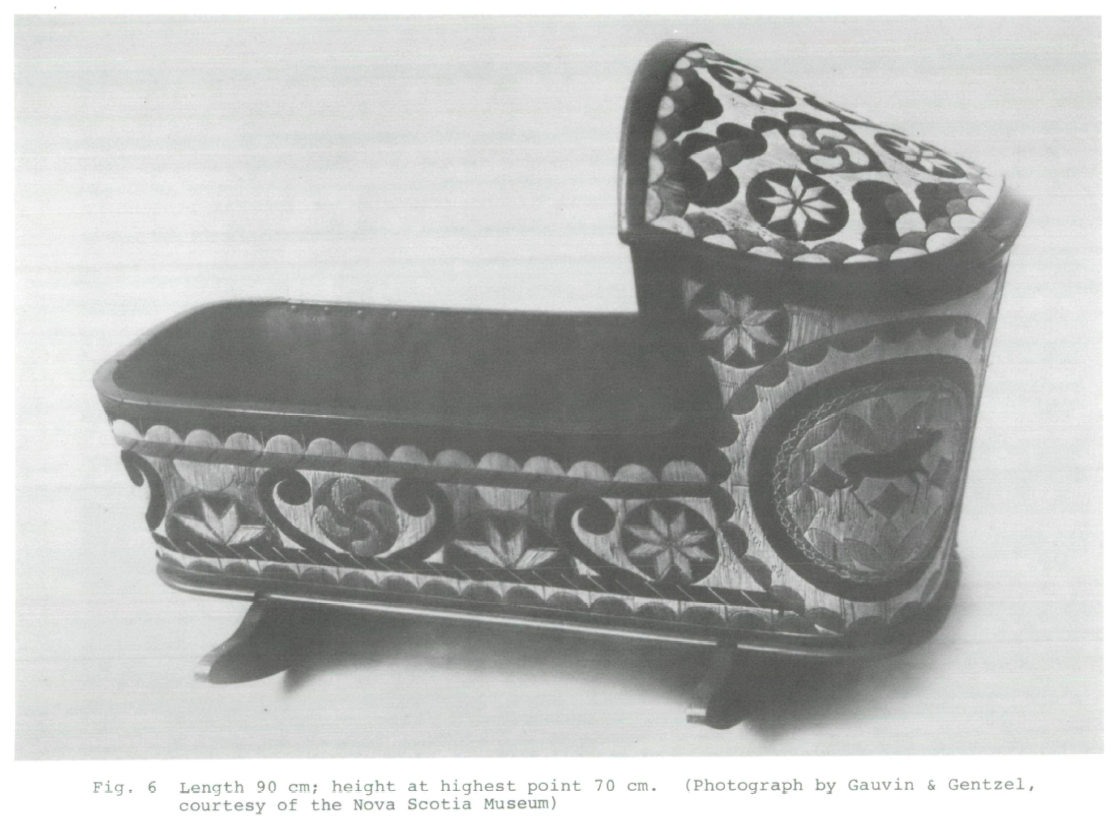

14 When a son was born to her friend Reuben Rhuland in 1868, Christina began making a cradle for the baby. This cradle (fig. 6 ) , now in the DesBrisay Museum, is the only piece of her quillwork which survives; it shows her to have been a master quiller. When it was done she told Rhuland that its panels matched those she had once done as a gift for the infant Prince of Wales.21 Mrs. Rhuland's brother, Alexander Strum, made the wooden frame and mounted Christina's panels. A Strum family story says the actual quilling took a year to complete;22 Christina was assisted in this by her son Joe. In 1917 an elderly Micmac, Tom Labrador, told of seeing her at work:

15 Rhuland sold the cradle to a John Doering a few years later. In 1917, when Doering wished to dispose of it to the Provincial Museum, he asked a Bridgewater lawyer, W.E. Marshall, to write to Piers for him:

16 Christina Morris was said to have died in 1886. Micmacs who still remembered her in 1917 told Piers she might have been living at Newport Station, Hants County, at the time of her death.25 Piers, however, interviewed one of her neighbors, who said her death occurred at Chocolate Lake:

17 "She was a pious woman, of excellent character," 27 writes Piers, summing up rather dryly. From the portraiture that survives her, she was also a beautiful and intriguing woman. She deserves a place among the Nova Scotia artists who painted her as an artist in her own right and a place in the history of Halifax as one of its more interesting nineteenth-century citizens.