Article

Pointe Sainte-Anne:

A History of Acadians on the Saint John River

Abstract

In 1759, a brutal event occurred in the area now known as Fredericton. A company of rangers led by Moses Hazen raided the Acadian village of Pointe Sainte-Anne, scalped women and children who were over-wintering in the area until the snow melted enough for them to flee north to Quebec. Yet the historical narrative of the area has only passing mention of the Acadian presence in Fredericton. This article re-centres the French presence on the Wolostoq River, their role in maintaining alliances with the Wabanaki, and the displacement and upheaval caused by the imperial contests between Britain and France.

Résumé

En 1759, un incident brutal a eu lieu dans la région qu’on appelle aujourd’hui Fredericton, quand un régiment de rangers dirigé par Moses Hazen a attaqué le village acadien de Pointe Sainte-Anne. Ils ont scalpé des femmes et des enfants qui passaient l’hiver dans la région en attendant la fonte des neiges pour fuir au nord vers le Québec. Le narratif historique de la région mentionne seulement en passant une présence acadienne à Fredericton. Le présent document recentre la présence française sur la rivière Wolastoq, son rôle dans le maintien des alliances avec les Wabanaki, ainsi que le déplacement et le bouleversement qui ont été engendrés par les concurrences impériales entre l’Angleterre et la France.

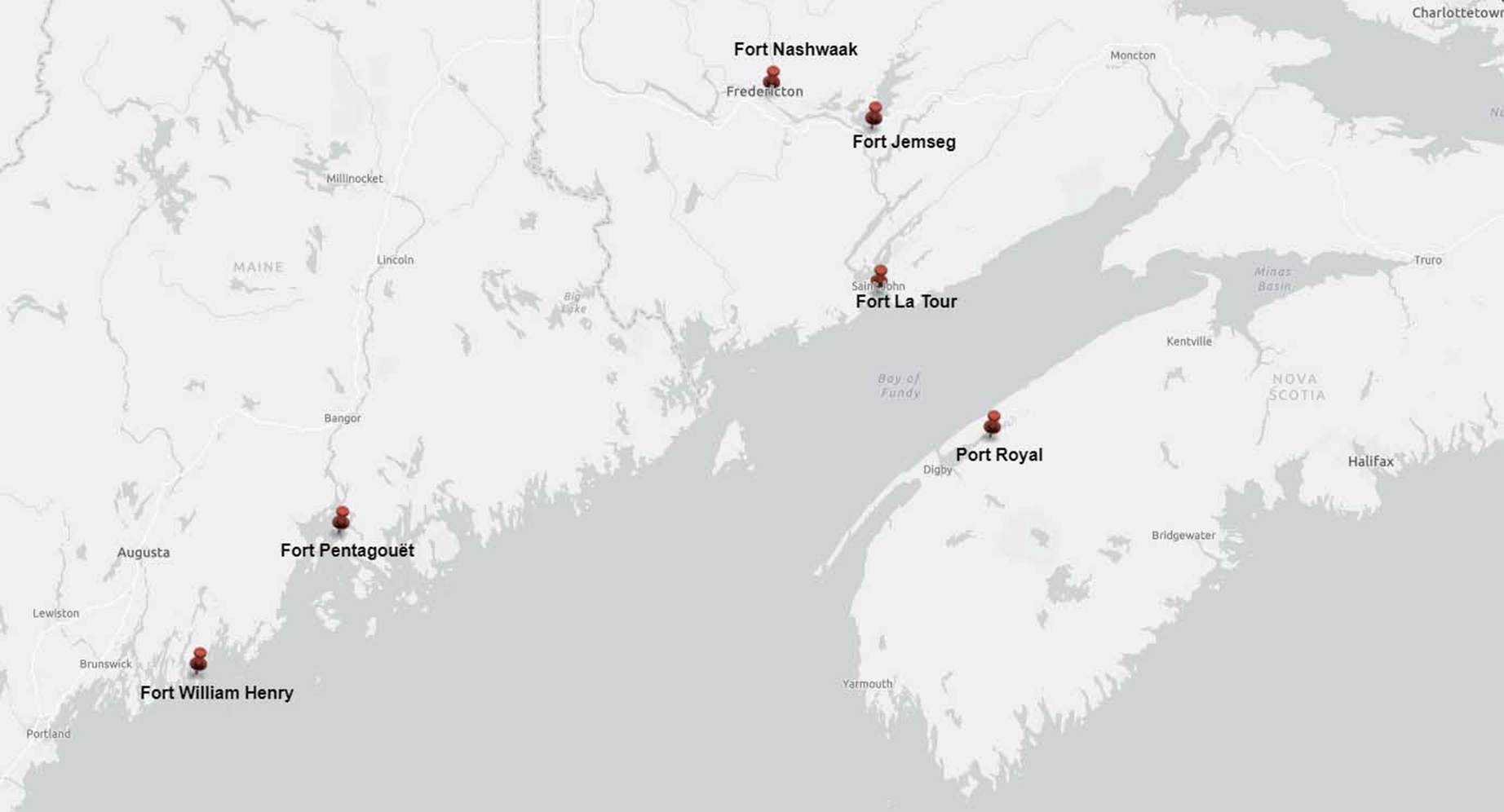

The Wolostoq River, since renamed “Rivière Saint-Jean” by the French, figured prominently from the very beginning of French colonization of the Atlantic coast. Noted by Champlain in some of his earliest maps of the region (see Image 1) and fortified by Charles de la Tour who built a trading post and fortification at the very mouth of the river in present-day Saint John, the river served as an important highway for trade with the Wabanaki. It was a major access point to inland navigation. The soil along the riverbank was noted as being very rich and suitable for cultivation.1 The region captured the attention of competing empires, including the Dutch, but the primary source of conflict for the fight to control the Saint John River would be the British, who settled the nearby colonies of New England. From the establishment of Massachusetts in 1629 to the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, control of the Saint John River would remain key to the French, and a thorn in the side of New England. While it would take over a hundred years to displace the French from the river, the displacement was so brutal, and so thorough, that history has almost forgotten they were ever here. This article seeks to restore the Acadian narrative of the “rivière Saint-Jean”: the French legacy of settlement, of how the river was used to facilitate trade and relationships with Wabanaki neighbours, and how they were ultimately displaced by the Seven Years’ War, the deportation, a troop of New England Rangers, and, finally, the Loyalists.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

1 Despite early interest in the river valley, no serious efforts were made to colonize the river until the 1670s, during Hector d’Andigné de Grandfontaine’s short tenure as governor of Acadie (1670-73). In 1654, Acadia was taken by Robert Sedgwick, a puritan from Massachusetts, general of the fleet and commander-in-chief of the New England coast. Ordered by Oliver Cromwell to make reprisals against the French for attacks against English merchant ships by French privateers, Sedgwick saw this as an excellent opportunity to take the resource-rich colony of Acadia, weakened by the civil wars between Charles de la Tour and Charles de Menou.2 Thomas Temple became acting governor of the colony after buying out La Tour’s trading interests in the area and paying the debts incurred by Sedgwick in his operation to seize the French colony. Temple’s jurisdiction included most of the area around the Bay of Fundy, including the Saint John River and the coast of Maine to Pentagouet. He recognized the strategic value of the Saint John River enough to have a fort built at Jemseg, which was farther upriver than the French had fortified up to that point; while the mouth of the Saint John had always had some degree of French presence since the French had arrived in the area, there was no evidence of any European construction further upriver prior to Fort Jemseg. Once the Treaty of Breda (1667) returned control of the area to the French, the colonial administration of New France also recognized the strategic importance of Fort Jemseg, and so its continued fortification became a priority.3

2 Just as important as the fortification of the river was a drive to increase French settlement of its banks. However, Grandfontaine’s attempts to attract colonizing seigneurs were not very successful. Of the four seigneurial grants recorded during his tenure, all but one were absentee landlords, and none of them really managed to bring in colonists. The most successful of these four seigneurs, Pierre de Joybert, Grandfontaine’s second-in-command, was not very successful at all. Captured by Dutch pirates from Fort Jemseg in 1674 and taken to Boston, he was held for a ransom of one thousand beaver pelts, which was eventually paid by Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac. The need to rescue Joybert alerted Frontenac to the vital corridor presented by the Saint John River for both trade and transport and the vulnerability it posed not only to Acadian trade networks but to the Saint Lawrence River. The Saint John could potentially serve as a corridor by which New Englanders could infiltrate other parts of New France if they were permitted to control it. That its fortifications could so easily be captured by pirates was deeply concerning. The governor’s solution was to secure the river against incursion by working to secure its colonization by French settlers.4

3 Once returned to Acadie, Frontenac rewarded both Joybert and his brother with grants along the river, with the express intent of populating those grants. In 1677, Pierre Joybert was given an additional grant along the Nashwaak (present-day Fredericton), with further instructions to clear the land and bring in more French settlers. However, Joybert did not get very far into his settlement project before his death in 1678. His role as administrator in Acadie was taken over by Michel Leneuf de la Vallière, who settled his family and his coterie of colonists on the Chignecto Isthmus rather than on the banks of the Saint John.5

4 It was the Damours family who managed to successfully colonize the banks of both the Saint John and the Nashwaak. Mathieu Damours de Chauffour was one of the first members of the conseil souverain in Quebec. He was a member of the French nobility, and possessed several seigneuries in Anjou, France. Damours’s father was a councillor of the king, making the family both very well placed and extremely influential in political and noble circles. The Damours brothers—Mathieu, Louis, and René—obtained grants along the Saint John, Richibucto, and Nashwaak Rivers. These grants included not only the former seigneurial grants of Pierre Joybert and his brother, but also present-day Meductic, Fredericton, and Marysville, and stretched down to Jemseg. Louis Damours de Chauffours was the seigneur of the area around the Nashwaak River, which eventually included Fort Nashwaak and Pointe Sainte-Anne. René Damours de Clignancour’s seigneurie was around the Meductic area, while Mathieu Damours de Freneuse was the seigneur of the Jemseg area.6 The brothers were very successful in both their cultivation of the land and their colonization efforts; they not only established large areas of farmland, they even established lumber and grain mills.7 While their formal seigneurial grants date to 1684, Louis Damours was present in the area building trading posts and residences at least two years prior to the acquisition of the land grant.8 By the time their grants were surveyed in 1695, the Damours had cultivated 130 acres of land, had almost sixty acres of pasture, and had produced over six hundred bushels of produce and grain in the prior year alone. Their settlement included forty-five French settlers, which was a significant increase from the five recorded by de Gargas in 1688.9

5 The project to secure the Saint John River on behalf of the French was taken up again by Governor Villebon. Joseph Robineau de Villebon was the son of René Robineau de Bécancour and Marie-Anne Leneuf de la Poterie, baptised in Quebec in 1655 but likely spent most of his childhood in the area of Trois-Rivières, where his grandparents had settled in the mid-1630s.10 His mother, Marie-Anne Leneuf, was the sister of Michel Leneuf de la Vallière, who became the seigneur of Beaubassin in 1676, and had his own short run as governor of Acadia in 1684-85. By the time Villebon arrived in Acadie in 1685, he had extensive history of serving in military campaigns both in France and New France. His first assignment in Port Royal was to assist Governor Perrot, and after him Governor Meneval, but was away in France when Phips sacked the settlement in 1690. Villebon returned from France in June 1690, just weeks after Phips had left for Boston with fifty prisoners—including the governor, Meneval. This left Villebon as the default administrative head of the colony of Acadie. A year later, Villebon’s position as default head administrator was formalized by the king, who appointed him governor of Acadia.11

6 As governor of Acadie, Villebon was responsible for maintaining good relationships with the Wabanaki, encouraging the Abenaki in particular to maintain their alliance with the French rather than the English, and to use that alliance to wage “continual war” against New England.12 The goal was clear: Villebon’s mission was to not only secure the colony of Acadia; it was to use the strategic position of Acadia and its generally favourable relations with its Indigenous inhabitants to keep the British away from the St. Lawrence River. Acadia was a buffer zone. Governors in New France were tasked with execution of military strategy, as decided by Paris and the colonial administration in Quebec. Orders were issued by Governor Frontenac, who, as governor general, was the head of New France’s military and represented the king in diplomatic relations. “Regional” governors, such as Villebon, were responsible for executing the orders of the governor general; they had no power to execute military orders or strategy without approval of the governor general. The discussion of Acadia’s administration has often been overshadowed by the history of British administration, which was very different. While New England’s governors answered only to London, New France’s regional governors answers to the governor general and the intendant of New France. New England had no such governor general, and no colonial official equal to the intendant. The governor of Massachusetts could unilaterally declare war on Acadia with the approval of only the Crown; the governor of Acadia had no such authority. Only the governor general of New France could issue orders that dealt with international diplomacy (which included relations with Indigenous peoples) and military policy. This is a necessary lens through which Villebon’s actions must be viewed, and which is far too often cast aside. Instead, scholars interpret Villebon’s military actions as if they were his own unilateral decisions.13

7 The first such military action undertaken by Villebon was to re-establish French fortifications on the Saint John River, an action greatly encouraged by Frontenac. Port Royal was not only strategically vulnerable as a colonial administrative centre, a fact proven over and over again by a succession of raids by both the British and the Dutch, but its security was being further deteriorated by its decreasing population. Families were spreading out further and further away from Port Royal, migrating in groups to places like Beaubassin.14 Seeing Fort Jemseg as inherently vulnerable, he set out to establish a brand new site further upriver, at the mouth of the Nashwaak. Although he named the new fortification “Fort Saint-Jean,” hardly anybody called it that; the name of the river, Nashwaak, was almost immediately substituted for the official name by everyone except Villebon himself. While Fort Nashwaak was being built, Phips was rebuilding Fort William Henry (see Image 2).15

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

8 Fort William Henry at Pemaquid was central to the imperial and colonial competition between the English and the French in North America, and was at the core of a land border dispute which continued for over a century. The French believed the borders of their colony existed as far south as Fort Pentagouet, built at the mouth of the Penobscot River in present-day Castine, Maine. The tensions in Pemaquid dated to the return of the colony of Acadia to French hands by the Treaty of Breda, when Grandfontaine attempted to definitively establish the southernmost border of Acadie at the Kennebec River, without success.16 Fort William Henry, constructed in 1692 in present-day Bristol, Maine, on top of the ruins of several other forts which came before it, was a response to demand to secure the northern border from the French and the Abenaki, who had come within seventy miles of Boston by destroying every English settlement in their path.17 For a few years, these two forts became the primary sites of skirmishes between the English, French, and Wabanaki; the French, with the help of the Wabanaki confederacy, would raid Fort William Henry, and the English would raid Fort Nashwaak. In 1696, Fort William Henry was destroyed once again after being captured by the French in a military campaigned led by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, decorated officer of the Compagnies Franches de la Marine.18 In retaliation, Benjamin Church led a force from Massachusetts against Fort Nashwaak in September of that same year. While his forces failed to take Villebon or the fort, his nine-day raid proved devastating for Beaubassin, which saw their houses and barns burned, their livestock killed, and their crops destroyed.19

9 Although Church had not achieved his goal at Nashwaak, there was at least one prominent French settler who was a casualty of his raid on the fort: Mathieu Damours de Freneuse, who had settled the area with his brothers. Fort Nashwaak had at least two weeks’ notice of Church’s arrival; a canoe had arrived with word of an English ship arriving at Fort Menagoèche with two hundred men aboard, giving the fort plenty of time to rally support—including the Damours brothers from neighbouring settlements. Mathieu Damours de Freneuse was ideally placed on the river in Jemseg to hear news at it came both from Menagoèche and Fort Nashwaak, and likely would have proceeded to Nashwaak immediately to help in its fortification. Unfortunately, this ideal placement also made him vulnerable; Church’s troops would have come upon his farm as they were proceeding downriver back to the mouth of the Saint John River. Taking out their frustration over their lack of success, the New England raiders attacked the Damours farm, setting fire to the house and the barn, and killing the livestock. Soon after, Mathieu Damours died of exposure.20

10 When Villebon died in 1700, the fort that he established at Nashwaak fell into disuse, and the administrative capital returned to Port Royal. However, the colonial French population of the area largely stayed, and did not migrate with the administration. Exact population numbers are unclear, but some Acadian families were already concretely established in the Fredericton area by 1700, including the Martel family and the Godin family. After Acadia was once again ceded to the British in 1710, more families began to migrate to the Saint John River valley. Unfortunately, we do not have a clear picture of the population movement towards the area. While archival records hold a number of census documents, partial census documents, parish records, and lists of names of heads of household for peninsular Nova Scotia, Cape Breton (Ile Royale) and even Prince Edward Island (Ile Saint-Jean) in the eighteenth century, there exists almost no archival record of the French population of the Saint John River in the first half of the eighteenth century. The documents that remain indicate the existence of at least two significant Acadian settlements on the Saint John River by the 1730s; one at Jemseg, and the other at Pointe Sainte-Anne or present-day Fredericton.21

11 One of the first detailed surveys done of the area was by a Père Danilou in 1739. By this time, the settlement around what was formerly Fort Nashwaak was known as Pointe Sainte-Anne by the French and Sitansisk by the Wolostoqiyik. It’s not entirely clear when the French name changed, but by the 1730s, the name “Pointe Sainte-Anne” was used in French documents to refer to the area. The 1739 census indicated about a hundred French settlers in the area between Pointe Sainte-Anne and Jemseg. The families listed by Danilou in the region included the Godins, the Laforêts, the Boisjolies, and the St. Aubins, among others. He also enumerated some of the residents of the nearby Wolostoqiyik village of Aukpak, which would have been located around present-day Kingsclear.22 The Wolostoqiyik had been farming the area for centuries, growing wheat and corn on the riverbanks. All indications seem to signal a solid trading relationship between the French and Indigenous communities of the area.23 This relationship was maintained primarily by Joseph Godin, patriarch and community leader of Pointe Sainte-Anne.

12 Godin’s father had arrived in the Nashwaak area in the 1680s, granted a piece of land by Villebon who employed him as an interpreter. Gabriel Godin was known in the colonial community for his aptitude in local Indigenous languages and served as interpreter between the Wabanaki people and the French government at Nashwaak. When the government administration returned to Port Royal, the Godin family remained. Joseph Godin refers to his father later in life as the “founder of Sainte-Anne.” Like his father before him, Joseph proved proficient in languages, and served as an interpreter between the French and the nearby Wabanaki peoples. His primary role was to maintain good relations between the French, the Wolostoqiyik, the Mi’kmaq, and the Penobscot. Every year he would travel to re-negotiate local treaty terms with representatives of these tribes.24 This was an important element of the relationship between the French and the Wabanaki; treaties were not treated as static but as living relationships that needed to be renewed and maintained with gifts and demonstrations of friendship.25

13 This maintenance of good relationships has been viewed by many scholars as a way to control the Wabanaki. Rather than being spoken of as a mutually beneficial relationship, the Wabanaki people are often viewed as mere pawns of the French. Rather than deciding for themselves to attack the British for settling on Wabanaki lands without permission, they were “egged on” or “encouraged” to do so by the French. This retelling of the history of Wabanaki relations between colonial powers does three things. First, it removes the agency of the Wabanaki, recasting them as mercenaries instead of sovereign nations with their own reasons to attack foreign invaders in the area. Second, it invalidates any claim the Wabanaki have over their own homeland, recasting the imperial struggles over Acadia as being purely a matter of European concern. Why else would the Wabanaki get involved in European wars? Third, it completely denies the control Wabanaki peoples still held over large portions of the territory considered “Acadia” well into the eighteenth century. While European powers might have managed to take control of the coastal areas of New France and New England fairly quickly, the inland river systems were a complete mystery to them. John Gyles’s account tells of how he was transported away from his family after being kidnapped using a tangled network of inland river and portage routes until he eventually ended up in the Saint John River valley. Even Col. Robert Monckton was completely unable to navigate the opening of the Saint John River without guidance in 1758.26 Acadia existed as an “imperial fiction” within a territory still governed by the Wabanaki, and colonial powers ignored this reality at their peril.27

14 Beyond the implications of military strategy, the French depended on the Wabanaki people for their survival, and so maintaining good relationships was crucial. Yet government officials at Annapolis Royal—and later at Halifax—were not interested in maintaining relationships. Their efforts lay solely in imposing the European-style treaties on the Wabanaki, controlled by documents signed by all parties that would be honoured by all until otherwise revoked, without the constant need for re-negotiation.28 The fact that Joseph Godin and the French of the Saint John River continued their constant re-negotiation of their relationship with local Wabanaki people made the Godins look inherently suspicious in British eyes, a view that survived into the modern-day narrative of the French settlement of the Saint John River. Possibly the most egregious example of the permeation of this narrative is Joseph Godin’s entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, which portrays him as a militia captain who was leading a full-fledged resistance from Pointe Sainte-Anne starting in 1749.29

15 We can be fairly certain there was no militia uprising from Pointe Sainte-Anne, led by Godin or anybody else. Unlike many Acadian towns destroyed during the deportation, we have a number of documents that detail Pointe Sainte-Anne’s demise, and all of them make it clear it was not a threat. The destruction of the village took place in the winter of 1759 and was the crux of a thirteen-month long campaign to clear the Saint John River of Acadian inhabitants.

16 In the summer of 1758, the deportation of the Acadians from the maritime region had been underway for three years. Louisbourg had fallen to the British and New England forces a second time, and Acadians found themselves with fewer and fewer places to flee. A massive movement had been underway to move north, towards the St. Lawrence River, and in many cases, the Saint John River was one of the stops, if not the first stop, for refugees moving north towards Quebec. Much like the population movements following the capitulation of Port Royal to the British in 1710, we do not have a clear picture of how many Acadians made their way to the Saint John River between 1755 and 1758. We do, however, know that the French population of the area swelled during that time. Once the campaign at Louisbourg was over, Monckton was given new orders: to clear the Saint John River valley of French inhabitants.30

17 Monckton arrived at the mouth of the Saint John River in September 1758 with a company of British regulars as well as a company of New England Rangers led by Capt. McCurdy. Founded by Benjamin Church, the New England Rangers had as their goal the protection of the New England colonies from Indigenous raids by emulating Indigenous battle style. By 1758, almost all of the rangers were born in New England, and their service against the French at Louisbourg and the Saint John River was their first time leaving the immediate confines of their hometown. They had been brought up to believe that the Acadians, or “French Neutrals,” were savages, that they were the ones convincing the local Indigenous tribes to attack them and to burn their houses and threaten their livelihoods, and that the French and the Indigenous people were in league together and one was no better than the other.31 The British regulars were much more traditional in their training and battle style; they were professional soldiers who did this work full-time, and had likely fought in many other battlefields.

18 During his time on the Saint John, Monckton kept a detailed journal that included copies of the letters and reports he sent to his superiors. It gives us an excellent insight into both the successes and failures experienced by his troops, along with their mission goals. The first thing they did when they arrived was set about rebuilding the old French fort at the mouth of the river, which they renamed “Fort Frederick.”32

19 In November, Monckton wrote a detailed account of his troop’s activities clearing out French residents. He mentioned an Acadian informant who was helping the troops navigate the river, presumably against his will: a prisoner sent to them from Fort Cumberland, formerly Fort Beauséjour. He mentioned that this prisoner had been taken two years before in his attempt to flee the area, and that his family had already been sent to Ile Saint-Jean, or Prince Edward Island. His primary job was to serve as pilot up the river, as nobody serving under Monckton had any experience. The British troops had already been told their vessels were too large to navigate very far, but they could not navigate upriver with smaller ships and still provision their troops, carry their cannon, and take prisoners. So they proceeded, lost two ships to the Reversing Falls before discovering the effect of the tides on navigation, and then once again attempted to proceed upriver. They got as far as Grimross, or present-day Gagetown.33

20 The destruction of Grimross is one of the better-known events of New Brunswick’s deportation history, thanks to a rather famous contemporaneous image done by Thomas Davies called A View of the Plundering and Burning of the City of Grimross34 (see Image 3). Depicting the fire that destroyed the town, smoke billowing into the air, and English ships waiting in the river, it’s the only known image that depicts the deportation as it was happening. Monckton’s journal describes the raid as a success, despite not having captured any of “the enemy.” The Acadians who were presumably inhabitants of Grimross at the time were seen fleeing upriver in canoes just as Monckton’s troops arrived.35 The destruction of their houses, food stores, and cattle would have been devastating enough to assure they would not return; this was November, and winter was just about to set in. The residents would have been left entirely without food stores, without shelter, even without any livestock to provide them with milk or eggs. They would have been entirely destitute just as the cold weather was setting in.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

21 But Monckton’s luck was also turning sour at this point. When the company attempted to continue upriver to Pointe Sainte-Anne, two of his ships ran aground. As he had been warned, the vessels drew too much water, and the river was too shallow. They were forced to turn around and return to Fort Frederick, burning all the buildings they found on the way and killing all the livestock they came across. Rather than trying to reach Pointe Sainte-Anne a second time, his November 1758 report includes a series of justifications for leaving Pointe Sainte-Anne as is: First, even if they did manage to get that far upriver, they barely had enough provisions at Fort Frederick to supply the company that was currently there, and could not afford to provision prisoners for the winter. Taking any remaining residents of Pointe Sainte-Anne prisoner would therefore be cruel, as they risked starving to death. Second, his informants had told him that there was no hint of cannon or fortification in the area. And third, he had already been informed by multiple sources that any remaining French residents on the river were fleeing north under their own power, heading for “Canada,” or the St. Lawrence River. Why waste more resources on a problem that was clearly fixing itself?36

22 The threat posed by Pointe Sainte-Anne in the autumn of 1758 is a point of debate even today. In an article discussing the Saint John River campaign, Geoffrey Plank cites a British official “with first-hand knowledge of Pointe Sainte-Anne in 1758” named William Martin, who claimed that the village held not only a hundred Acadian families, but a small fighting force.37 If that were the case, whatever military presence that might have existed in Pointe Sainte-Anne had ceased to be a threat by November 1758, according to Monckton’s account; there was no cannon, no fortification, and no troops—only stragglers fleeing north.38

23 Had Monckton remained in charge of the garrison at Fort Frederick, this status quo might have been maintained, and the residents of Pointe Sainte-Anne might have been permitted to overwinter in peace before heading to Quebec in the spring. However, Monckton was recalled to Halifax in mid-November before being dispatched to Quebec, where he eventually served at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. He took most of the British troops with him, leaving Capt. McCurdy and his rangers in charge of Fort Frederick.39

24 We have several very detailed accounts of what happened next, from newspaper articles and contemporary journals, written by a British officer who remained in the area, to a letter written by Joseph Godin himself. In January 1759, the river froze, leaving the rangers at Fort Frederick feeling much more exposed than they had felt when the water was open. The freezing of the river solved the issue of how difficult it was to navigate; suddenly anybody with a pair of snowshoes could easily access their position. Gaining knowledge of who exactly remained upriver became a much more urgent matter, and so they began planning scouting missions to Pointe Sainte-Anne to take stock of the French population there. On their first attempt, McCurdy was killed by a branch that fell off a tree, and the troops that accompanied him returned to the fort. His replacement, Moses Hazen, was duly appointed in his stead.40

25 Born in Massachusetts in 1733, Hazen joined the rangers in 1755 at the outbreak of the war with the French. He served in Louisbourg before being ordered, along with the rest of McCurdy’s company, to the Saint John River. When he took over McCurdy’s position, he also took over the mission to scout the population at Pointe Sainte-Anne. Towards the end of February, he gathered about twenty men and headed upriver a second time. The result of this mission was a slaughter, an incident known as one of the most notoriously cruel and disastrous events of the deportation.41 Joseph Godin, who ended up eventually being deported to France, where he and his wife lived in destitution, wrote about the events of that day in a letter to the king in the 1780s. His tale is harrowing, even 250 years later.

26 Written in Cherbourg, France, in 1776, Godin told the story of how his father settled the area of Sainte-Anne, and how his family lived a prosperous and peaceful life. He spoke of his role as an interpreter for the king, and how he sometimes even spent his own money on gifts to assure that the relationship between the French people and the Wolostoqiyik remained peaceful. Although he stated that he was a militia captain, he does not mention any military action taken as part of this role.42 And he explained how this all changed when the English arrived and started attacking the French communities along the river. In the winter of 1759, he and his family were waiting for spring to arrive before leaving the area for the Saint Lawrence River valley—as community leader, he had felt obligated to stay behind and make sure that members of his community navigated their way upriver safely. His was the last family remaining, and they were just waiting for good travelling conditions. The little group consisted of his son-in-law, Eustache Paré, son of Pierre Paré and Jeanne Dugas, of Louisbourg, his wife, Anne Bergeron, his daughter, and Godin’s grandchildren. When they saw the rangers approaching, they fled to the woods, but they were found. Hazen’s company did not restrict themselves to burning their buildings, killing their livestock, and destroying their food stores. They tied Godin and Paré to trees, and forced them to watch as they tortured and killed Paré’s wife, Godin’s daughter, before killing her by scalping.43 Watching this happen, Godin’s wife, Anne, grabbed the grandchildren and fled further into the woods, without food or any supplies, only to be captured later and taken prisoner. Hazen declared that Godin and Paré would be taken to Fort Frederick, where their status as militia captains would be used to trade for prisoners taken by the French; but the military commanders of Port Royal recognized the futility of this proposed exchange immediately upon the arrival of these prisoners. A militia captain and his son-in-law had no actual standing in the French military. They were not commissioned officers. They were sent to Fort Cumberland, and from there eventually deported to Boston, then back to Nova Scotia, then to England, and sent on to Cherbourg. Godin describes the utter misery of this shuffle: the poor conditions on the ships, the rotten food and lack of drinking water, the disease and filth, and the people who died just from exposure.44 Even after Hazen’s raid confirmed that Pointe Sainte-Anne was not populated, the New England Rangers could still not shake the anxiety of imminent attack by the Acadians of the Saint John River, and conducted two more raids before Acadians finally approached Fort Frederick in October 1759 suing for peace, having heard of the fall of Quebec.45

27 When the Seven Years’ War finally ended in 1763, Acadians started to trickle back into the Saint John River valley. Many of them did not have to travel far; some had only gone upriver to the Madawaska area, or to the St. Lawrence River valley. When they returned to the Pointe Sainte-Anne area they found nearby Maugerville had been settled by a group of New Englanders called “Planters,” but managed to maintain friendly relations and a good trading relationship with both the planters and the New England merchants who traded with them until the 1780s. It was only with the arrival of the Loyalists that this dynamic changed. In 1783, the population of around 340 was suddenly disrupted by the arrival of over ten thousand settlers from Loyalist regiments who had been promised land to compensate for the losses they had sustained in the American Revolution. The very next year, the province we now know as New Brunswick was partitioned from Nova Scotia and created as a separate province to accommodate the Loyalist population, and all land grants had to be re-issued—even if they had already been settled and farmed for decades. Despite being re-granted their lands, most of the Acadians in the Fredericton area once again left for regions further upriver.46 Some remained in the area and have maintained a steady French population in the area now known as Fredericton ever since.

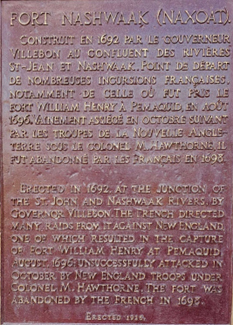

28 In 1926, a plaque was erected at the mouth of the Nashwaak, where the river flows into the Saint John River (see Image 4). Due to construction, it was recently moved to the north side of the Bill Thorpe Walking Bridge: a short, simple acknowledgement that the region we now call Fredericton once served as the capital of Acadie. Containing a paragraph in French, followed by its translation in English, it reads as follows:

For many Fredericton visitors and residents, this plaque, set in a stone cairn along the walking trail, is the only acknowledgement of the formerly thriving Acadian community that once existed where Fredericton now stands. There are other hints of its existence, such as Sainte-Anne’s Point Drive (or Promenade Sainte-Anne), named for the former village; the community’s French language school, École Sainte-Anne, and, since 2019, an exhibit at the Fredericton Region Museum dedicated to the history of the Acadians in the area. But this plaque is by far the most visible, has been visible for nearly a century, and is the cornerstone for the region’s misunderstanding of Acadians on the Saint John River: they were here for a short time, and now they are not.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

As the recent dialogue around historical monuments and the tearing down of statues has more than adequately discussed, public monuments such as these are not necessarily the best avenue for teaching local history.48 The plaque at the end of the walking bridge certainly leaves a lot to be desired, as do many of these commemorative historical monuments throughout the country. The history of Pointe Sainte-Anne has been so thoroughly displaced in favour of the founding mythology of Loyalist Fredericton that Acadians who live here today often themselves feel displaced. The research for this article was the result of a museum exhibit at the Fredericton Region Museum that opened on the fête nationale of August 15, 2019. Many Acadian patrons approached me to tell me how the exhibit made them feel like they belonged in this region, for the first time in their lives. This tells me the way we teach the history of the Saint John River is a huge problem. By erasing the historical narrative of the Wabanaki, of Acadians, of anyone who isn’t a descendant of the Loyalists who arrived in the 1780s, we are creating a sense of displacement within our own population. We are exacerbating, if not causing, the “us versus them” narrative we see play out so often in debates over language rights, Indigenous land claims, and so many other issues. It is time to return to a more holistic version of New Brunswick’s history.

To comment on this article, please write to editorjnbs@stu.ca. Veuillez transmettre vos commentaires sur cet article à editorjnbs@stu.ca.