We Left Our Mark on This Land

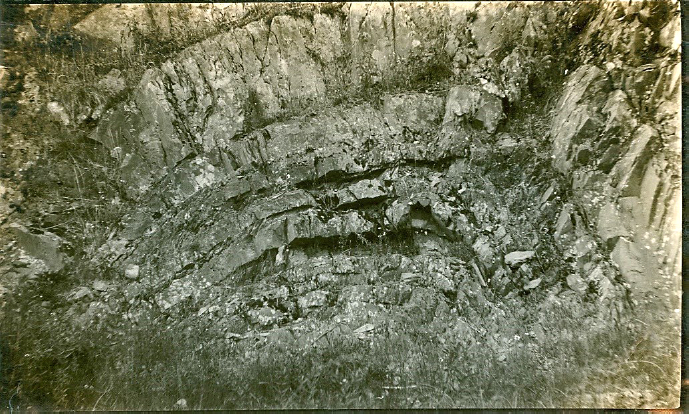

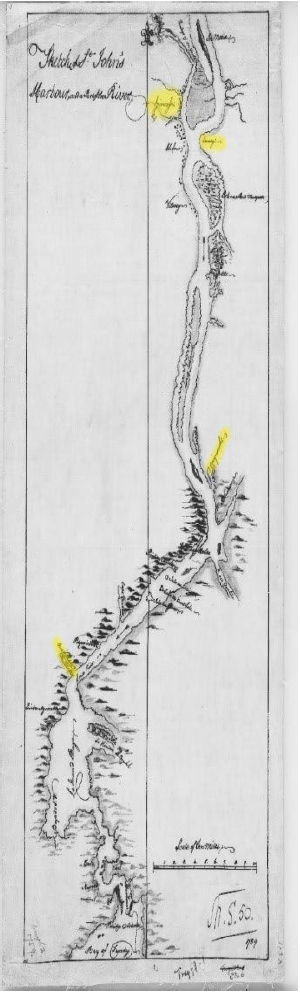

1 Over thirteen thousand years ago what we now know as Fredericton was covered by a huge glacier covering much of North America. As the glacier thawed, the meltwater flooded the land. When the waters did not drain, our ancestors discovered that giant beavers as large as seven feet high and ten feet long had built huge dams that held back the water. At the time, our people were living on the shores of what looked like a huge inland sea, in places that are now high ground. Quite recently tools of ours that are over twelve thousand years old were found near what is now Fredericton, in one of those high places overlooking the Nawicowək (the Nashwaak River).1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

2 One day, according to our traditions, our ancestors saw the great Kəloskap and his grandmother Monimkwehs (Woodchuck) arrive at Menahkwesk (now Saint John) in his stone canoe, which some said was actually an island.2 When we told him about the huge dams that the giant beavers had built, he put on his snowshoes, took his dogs, and started out after the beavers. Near Mekwtəkwek (Mactaquac) he fell against the cliff and left an impression of his face,3 which was long revered by our people until it was flooded by the Mactaquac Dam.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

3 A little farther on he took off his snowshoes and left them there. We called them Akəmeyal Mənihkol (the Snowshoe Islands), which are now also flooded by the Mactaquac Dam.4

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

4 Still trying to catch the beavers, Kəloskap threw two rocks ahead of them as they fled upriver. The rocks landed just below where the Tobique River is now and became known as Sopekwapskol (the Tobique Rocks). These, too, have been flooded by a modern dam, the one at Beechwood. Unable to stop the beavers Kəloskap continued chasing them. At what is now Grand Falls he found a huge beaver dam, and immediately tore it to pieces. As the floodwaters rushed through the gorge, the Wəlastəkw (St. John River) began to take shape above Grand Falls.5 According to John Gyles, the English boy brought here as a captive over three hundred years ago, our name for these falls was Checanekepeag,6 which was a reminder of this story of the beavers, since Kci-kani-kpihikən actually means “the big old dam.”

5 Kəloskap continued chasing the beavers as far as Lake Temiscouata, where they finally got away from him and took refuge in their nest known to us as Wəsəssik (Mount Wissik). He then returned to Menahkwesk and tore up the other huge dam built by the giant beavers at the place now known as Reversing Falls. It was in this way that the lower part of the Wəlastəkw took the shape that it is today.7 For the most part it is a calm, gentle river. That is why we call it the Wəlastəkw, since it means “the river of the good or peaceful wave.”8

6 Having now formed our river, Kəloskap was sitting one day with his brother Mihkəmowehs high above the Falls when he began to wonder how he might make it easier for people to canoe upriver. Suddenly he came up with the idea of tides that would run upriver for a while, then downriver for a while, and once he created them, they reached upriver as far as what is now Fredericton and the islands above.9 It is why we call this area Ekwpahak, which means “end of the tide.” To commemorate these great works of Kəloskap, one of our people pecked out an image of him, his dogs, and a beaver on a rock at French Lake, Oromocto.10

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

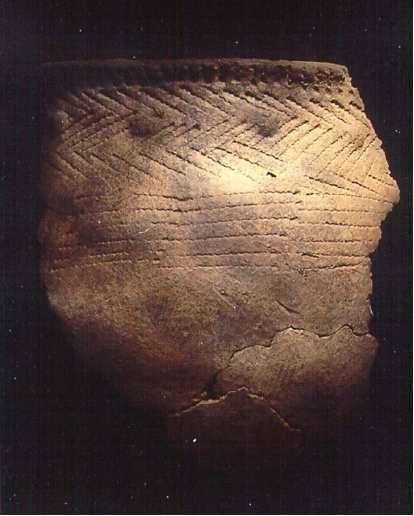

7 That our people continued to maintain a presence in the area of Ekwpahak is evident in the tools and utensils that they left here throughout our history.11

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

8 Over the millennia that we have lived on this river, we lived well off the land and the waters. Every summer we hunted sea mammals and other salt-water resources at both ends of our territory, on the Bay of Fundy to the south, and the St. Lawrence River to the north. During the rest of the year all kinds of foods and materials were readily obtained at different places in the watershed of the Wəlastəkw. Birch, spruce, basswood, and cedar supplied us with wood, bark, and roots out of which we made tools, canoes, wigwams, toboggans, snowshoes, and cradleboards. Moose, deer, caribou, muskrat, beaver, and bear supplied us with protein-rich food, as well as fur and hide for clothing and footwear, while ducks, geese, salmon, eel, bass, trout, and sturgeon added other sources of protein to our diet. Plants such as groundnuts,12 fiddleheads, butternuts, beechnuts, grapes, plums,13 berries, and even maple trees provided essential vitamins and other nutrients, while flagroot,14 wintergreen, cow parsnip, and a whole host of other plants provided medicines enabling us to cure ourselves of injuries and illnesses.

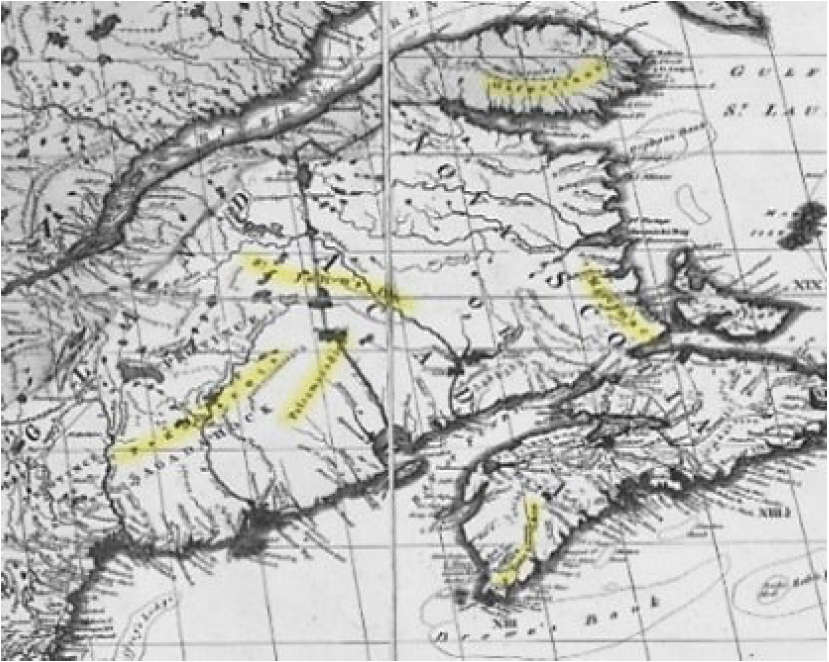

9 Although our main villages in the 1600s were at Mehtawtik (Meductic)15 and Menahkwesk (Saint John),16 Ekwpahak was so rich in resources it served as a natural site for annual gatherings, councils, and celebrations. We gathered here every spring to fish salmon, sturgeon, and bass; to gather fiddleheads; to plant corn, beans, and squash,17 and hold our annual gatherings and councils. The rest of the year we moved up and down our river in a regular yearly round that usually found us in different places at the same time every year.

10 In the decades prior to the arrival of Europeans on our river, it is likely that at least some of our people came in contact with European fishermen, explorers, and Basque whale hunters at Wahsipekosk (on the St. Lawrence River). From them we began receiving European trade goods in exchange for our furs. By the time French explorers and priests started coming to our territory in the early 1600s, both on the St. Lawrence River18 and at the mouth of our river,19 we were heavily involved in the fur trade and had begun to depend on European trade goods such as copper and iron pots, iron knives, axes, needles, and even foods such as flour, salt fish, and dried fruit. As for the priests, their mission was to convert us to Christianity, but in so doing, they began changing our form of life and our way of seeing the world. Sadly too, contact and trade with Europeans also brought repeated periods of deadly epidemic diseases and war. The diseases came in cycles from contact with strange European illnesses such as smallpox and measles to which we had no natural immunity. They are believed to have taken a terrible toll on Indigenous populations well before the first written records of our people emerged in the early 1600s.20 The wars were mostly between English, French, and occasionally Scottish and Dutch forces, who competed for our lands and furs, built fortresses, and from time to time captured each other’s strongholds.21

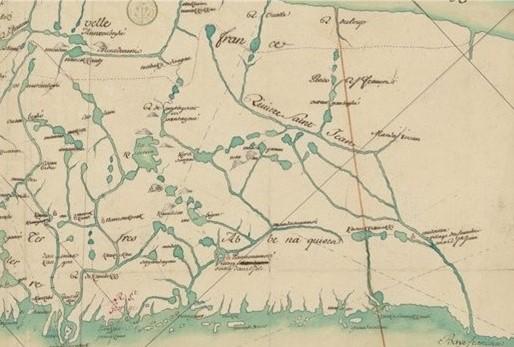

11 One phase of these wars continued until the 1670s when the French gained a tentative foothold in the region called Acadia, but now known as Maine and the Maritimes. Almost immediately French authorities began giving huge grants of land (seigneuries) on our river to French noblemen or seigneurs. In 1676 the Nawicowək (Nashwaak River) was granted to Pierre de Joybert, Sieur de Soulanges et de Marson, and the area from Ekwpahak north to Mehtawtik was granted to Rene d’Amour, Sieur de Clignancourt in 1684.22 Although these grants included exclusive rights to trade with our people, neither of these seigneurs kept records of their trade with our people.

12 While France was busy establishing seigniories in what is now the Maritime region, a major war broke out between New Englanders and Alnôbak (Abenakis) in what is now southern Maine. Known as the First Anglo-Wabanaki War (1675-78), it is now understood to have been caused primarily by English settler encroachments, racist provocations, and attempts to impose English sovereignty and law on the Alnôbak, all of which was compounded by a general lawlessness that characterized the frontier of southern Maine.23 Neither our people nor the Mi’kmaq were involved in this war, but the same causes would lie behind another conflict known as the Second Anglo-Wabanaki War (1689-99) that did involve us.24 This time some of our warriors joined our Wabanaki allies25 (in precisely the same way that Canada assisted their allies in both world wars in the twentieth century). It was in an attack on the English settlement at Pemaquid in August 1689 that the nine-year-old English boy, John Gyles, was captured and brought to Mehtawtik by our warriors.26

13 Once war was officially declared in Europe between England and France, French authorities in Quebec began supporting the Wabanakis to defend their lands, providing not only much-needed ammunition and supplies, but also military assistance. We joined this war primarily to support our Wabanaki allies. The French joined for a very different reason—to defend their claim to our land and that of all Wabanakis against the pretensions of the English. Since our relationship with the French had always been generally one of mutual respect cemented by the longstanding presence of French traders and missionaries in our midst,27 we welcomed their assistance. Indeed, the Recollet Father Simon-Gerard de la Place served at Mehtawtik from 1685 to his death in 1699 and was the first of many Catholic priests to live full-time with our people.28 That he and other resident priests also supported us in our struggles with the English certainly served to strengthen the bond between our people and the Catholic Church.

14 In 1691, two years after the start of King William’s War, a French officer, Joseph Robineau de Villebon,29 built Fort St. Joseph at the mouth of the Nawicowək (Nashwaak River), from which he directed the war effort against New England. Now with French forces established in the heart of our territory, our warriors became fully involved in this war. Until his death shortly after the end of the war, Villebon kept prolific records of the war effort, but apart from documenting a deadly epidemic that ravaged our village at Mehtawtik in 1694, his records contain very little detail about our people.30

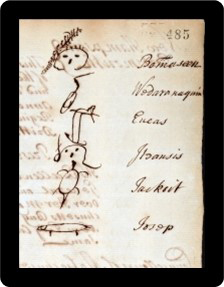

We Put Our Marks on the Documents: The Treaty of Portsmouth

15 This war ended in 1699 with the signing of a peace treaty to which we were not a party,31 although we had been involved in the war. A few years later another war known as the Third Anglo-Wabanaki War (1703-13) broke out between England and France, and quickly spread to the land of the Wabanakis, known as Wapənahkik. Preferring this time not to get involved in the war, many Wabanakis, including our people, withdrew to Catholic mission villages on the St. Lawrence. With hostilities taking place on both sides of our land, many of our warriors again joined our Wabanaki allies in war. To the east some helped the Mi’kmaq and Acadians to defend the French fort at Annapolis Royal against British forces. To the west others went to the assistance of the Panowapskewiyik (Penobscots) and Kínipekwiyik (Alnôbak of the Kennebec) in their struggle against the spread of English forts and settlements in their lands.32 After British33 forces captured the French fort at Annapolis in 1710, in what has been called “the conquest of Acadia,”34 our warriors participated in an unsuccessful attempt to retake the fort in 1711.35 After the war ended in Europe, France surrendered the territory known as Acadia to the British.36 Although this territory was said to have included our land and that of all Wabanakis in Wapənahkik, none of us had been consulted. We found out about it only when we joined our Wabanaki allies at a treaty conference with Massachusetts representatives of the British Crown in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, that summer. Not only were we informed that this surrender included our land, but also that it made us subjects of the British Crown, Queen Anne. So offended were we that one of the Wabanaki delegates was recorded saying that the French king “can give away whatever he wishes; for me, I have my land which I have given to no one, and that I will not give. I wish always to be the master of it. I know the boundaries and when someone wishes to live here, he will pay.”37 However, we were desperate for peace after more than twenty years of war, and since the treaty (of Portsmouth) promised at least to save “unto the said Indians their own Grounds & free liberty for Hunting, Fishing, Fowling,” the Wabanaki delegates signed it with their personal marks or totems.38 The marks of our delegates, Josop (Joseph)39 and Eneas, were an otter and a deer.40

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

16 Still disturbed about the claim that our land had reportedly been surrendered to the English, we confronted our priests who assured us that it was not included in the surrender,41 and that a newly established boundary commission would settle the matter in our favour.42 Unknown to us, a New England merchant who was present at the treaty table in Portsmouth admitted that the terms of this treaty had been deliberately not clearly translated to us.43 So while the treaty was meant to establish peace, it actually sparked another fifty years of unrest with frequent outbreaks of war in Wapənahkik. Great Britain now claimed sovereignty over all Wabanakis and demanded their subjugation to English laws, but Wabanakis continued to reject these claim, declaring that they had never surrendered their lands.44 Even if the treaty had been translated accurately, abstract European concepts such as “sovereignty” and “dominion” simply did not exist in Wabanaki languages, which thus led to profound misunderstandings.45

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

17 When we were later approached to swear an oath of allegiance to a new British crown,46 we refused. As far as we were concerned, the Treaty of 1713 had asked only that “we make our submission to [the British crown] in as ample a manner as we [had] formerly done” to the French crown. Since we had only been allies of the French, and not their subjects,47 we never had to swear an oath of allegiance to the French crown, so we saw no reason to swear one to the British.48 But with French traders now outlawed in Wapənahkik we found ourselves having to maintain cordial enough relations with British authorities at Annapolis to assure ongoing access to trade goods.

The Letter of 1721

18 On both sides of us, however, the unresolved issues festered quickly. Still greatly annoyed by the unauthorized presence of British forces in their territory, the Mi’kmaq began capturing vessels belonging to New England fishermen who had established a fishing station at Eskikewa’kik (Canso).49 To the west of us the Kínipekwiyik were still trying to stop Massachusetts from building new forts and settlements on their river, claiming them to be a violation of the Treaty of 1713 which promised to “save unto them their own Grounds.” But Massachusetts authorities were intransigent, suddenly claiming they had obtained decades-old deeds to lands on the Kínipekok from individual Alnôbak.50

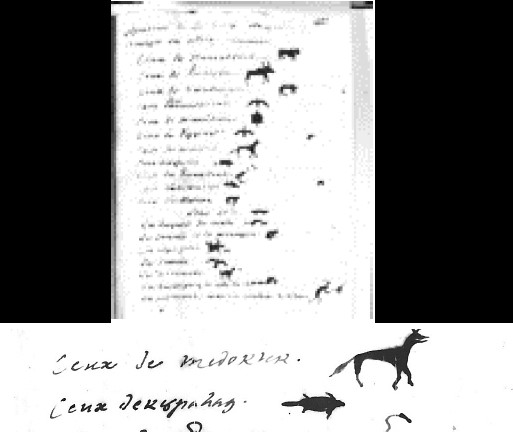

19 The Alnôbak, however, believed the deeds to be fraudulent, and having failed to make their point in conference after conference, they began killing cattle, and burning crops and buildings in the new settlements to warn off the settlers. When matters reached the boiling point in 1721, our people were summoned along with many other Indigenous villages on the St. Lawrence51 to go to the assistance of the Kínipekwiyik. In their village at Nalicowək (Norridgewock) a letter was drawn up warning Massachusetts authorities to remove all their forts and settlements from Alnôbakewey lands on the Kínipekok. It was then signed by over twenty-one delegates with either their personal marks or the marks of their respective villages.52 Among them were our delegates from both Mehtawtik and Ekwpahak who signed with a fox and a beaver, respectively.53

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

20 This was the first time that our village at Ekwpahak (on the south bank of the mainland opposite Ekwpahak Island) appeared in a document as a village of its own.54 Mehtawtik was clearly still the main village of our people, but Ekwpahak had been growing slowly, possibly for easier access to trade with English traders.

Mascarene’s Treaty (only X’-s)

21 When authorities in Massachusetts failed to heed the warnings in the letter, tensions escalated so quickly that war broke out again within a year. After Massachusetts declared war in 1722 and offered bounties on the heads of all “Eastern Indians,” some of our warriors joined the Kínipekwiyik and Panowapskewiyik once again. This time the French refused to assist the Wabanakis because of the peace treaty of 1713 between Great Britain and France. So, this war, known as the Fourth Anglo-Wabanaki War (1722-28), was waged by the Wabanakis alone, and much of this conflict took place at sea.55

22 After a particularly deadly attack by Massachusetts forces on the Kínipekwey village at Nalicowək in the summer of 1724,56 the war began to wind down. The Panowapskewiyik took the lead on peace talks, and by December 1725 they had negotiated a treaty known as Dummer’s Treaty for themselves and the Kínipekwiyik. They also initialled another treaty text known as Mascarene’s Treaty for the Peskotomukatewiyik (Passamaquoddies), Wəlastəkokewiyik, and Mi’kmaq to be ratified in Nova Scotia. On 4 June 1726, Mascarene’s Treaty was ratified in Annapolis by nearly twenty-five of our people along with many Mi’kmaq and Peskotomukatewiyik.57 Although none of our delegates identified their home village, it appears that they may have come primarily from Ekwpahak since a second ratification of the treaty was signed in 1728 by men from Mehtawtik. This time none of the surviving copies of either ratification contained the personal marks of the delegates, only an X beside each name.58

23 Mascarene’s Treaty was important to us for the promise of the British not to molest us in the exercise of our (Catholic) religion, or in our hunting, fishing, and planting grounds. It was also important as the first treaty signed with Nova Scotia. But since it contained many of the same alien and untranslatable concepts as in earlier treaties, it failed to resolve the issues of land and sovereignty that had led to this war.59 It raises the question as to whether or not it was carefully translated to us since we would not have knowingly consented to foreign or objectionable terms such as one declaring the king of Great Britain60 to be the “Rightful Possessor” of our lands, or one requiring us to accept British law in our lands.61 Further, while the treaty did not require us to surrender any land, it utterly failed to protect our land rights, saying only that we needed to respect English settlements “lawfully to be made.” It was these unclarified issues more than any other that would become the primary reasons for subsequent wars.62

24 In 1731 our priest, Father Jean-Baptiste Loyard,63 passed away after having served at Mehtawtik since 1709. Since a growing number of Acadians had begun moving to Ekwpahak from other parts of Nova Scotia about this time, Loyard’s replacement, Father Jean-Pierre Danielou,64 was appointed also to serve the Acadians in the Ekwpahak area.65 According to an early Acadian settler at St. Anne’s Point (now Fredericton), a small chapel was built there in this period to serve the growing Acadian community.66 Our people called this chapel Sitansis, our rendering of “Little St. Anne,” most likely since it was the second chapel in the area dedicated to St. Anne, the first having been the one in our village at Ekwpahak, called Sitan (St. Anne).67

25 At about the same time, more of our people began moving from Mehtawtik to Ekwpahak, in part, for the services of Father Danielou, who was stationed now at Ekwpahak, but also possibly for the opportunity to trade with the Acadian settlers. Due to the many issues left unresolved by the treaties, particularly the boundary issue, new conflicts arose in the 1730s. One resulted from abuses by private English traders. Another occurred when an English ship arrived at the mouth of our river to quarry limestone without our consent. And a third arose when surveyors from Annapolis arrived here to lay out grants for settlers. When we sent messengers to Annapolis to complain about these issues, authorities there seemed unwilling to address them. Some even expressed surprise that we claimed the land on the Wəlastəkok as ours.68 Conflicts similar to these had been plaguing our Wabanaki allies on both sides of us, but now they had come to our land. What is ironic is that English people who had generally compensated Indigenous peoples for their lands in other North American colonies, now believed that Utrecht “had absolved [them] from the necessity of compensating Amerindians for lands,”69 claiming without any documentation that the French had authority to surrender the land since they had previously obtained a surrender from the Wabanakis.

26 According to Father Danielou, relations with the Acadians were, in fact, not perfect. In a 1739 report on the state of the Acadian settlement at Ekwpahak, he wrote: “For the last thirty years we have suffered in silence the ill treatment of the Indians, the debts unpaid, the tributes70 which must be paid to them to which only Mr. the General71 was able to put an end to; the ravages of their hunting dogs.”72 This account attests to some troubling issues that were especially remarkable since one of our sakəmak (chiefs) at the time, Sosehp St. Aubin, was closely related to three Acadian families named St. Aubin who were living at Ekwpahak in 1739. As a Wəlastəkwewi Sakəm Sosehp St. Aubin had signed the ratification of Mascarene’s Treaty in 1726. His father, Charles, was one of two sons of Jean Serreau de St. Aubin,73 who had been granted a seigniory in Peskotomuhkatik (Passamaquoddy territory) in 1684, while his mother is presumed to have been a Wəlastəkwewi woman.

Treaty of 1749 (only X’-s)

27 With French traders still outlawed in Wapənahkik, our ongoing need for trade goods likely motivated our leaders to continue attending peace conferences with Massachusetts authorities. Such was the case when we heard early in 1744 that war was breaking out in Europe, yet again. This time, we sent four delegates headed by the son of one of our sakəmak to Annapolis to inform authorities there of our desire to remain neutral if war were to break out here. Unbeknown to us, however, war had already been declared in Europe between Britain and France, and within a week the Mi’kmaq and French began attacking British outposts in Nova Scotia.74 Thus began the Fifth Anglo-Wabanaki War (1744-49). Later that fall, a large number of our warriors joined the Mi’kmaq and Acadians in a month-long siege of the fort at Annapolis.75 The planned attack was eventually called off when British warships arrived. Almost immediately, Massachusetts authorities declared war on both the Mi’kmaq and our people, offering a bounty of £100 on the scalps of men and boys as young as twelve, and £50 on the scalps of women and children.76 We now had no choice but to become fully engaged in this war alongside our French and Acadian allies. Since our river was the major transportation route between Sikniktuk (Chignecto) and Quebec, we began seeing many parties of French soldiers and Indigenous warriors passing by our villages.77

28 With the threat of war now closing in on our river many of our people from both Ekwpahak and Mehtawtik withdrew to the St. Lawrence River and spent the winter near Quebec City. The group included Sakəm Sosehp St. Aubin as well as one and possibly two who would later be named as sakəmak—Francois deSalle and one named Nowel (Noel) who was likely the sakəm later identified as Noellobig or Nowel Topik.78 Over the next couple of years our warriors served with French and Indigenous allies in three arenas of the war, all at the same time. Some served at Sikniktuk, and some at Lake Champlain.79 Meanwhile, others assisted the Panowapskewiyik who had at first tried to remain neutral, but due to a clause in their treaty requiring them to join Massachusetts forces against us or be declared enemies, neutrality was not an option for them. As our long-time friends and allies they chose to join us and the Kínipekwiyik in war against Massachusetts.80

29 When the war came to an end in Europe in 1748, Great Britain and France signed another treaty of peace. Then in August 1749 our chiefs, Francois deSalle of Ekwpahak and Noellobig (Nowel Topik) of Mehtawtik, sent delegates to Kjipuktuk (now Halifax) to ratify Mascarene’s Treaty once again, but they each signed only with an X.81 Unfortunately for the British, only one Mi’kmaw chief signed the ratification since most of the Mi’kmaq were deeply angered by the large English settlement that had sprung up at Kjipuktuk that summer.82

30 Just over two weeks after our delegates went to Kjipuktuk to sign the treaty it was brought to our river and ratified by thirteen others of our people.83 Peace, however, was not to be. Within days of the ratification the Mi’kmaq went back to war and made a declaration claiming that it was the British who had destroyed all possibility of peace by settling on Mi’kmaw land at Kjipuktuk without Mi’kmaw consent. In an angry response, the new governor of Nova Scotia, Edward Cornwallis, offered a bounty on Mi’kmaw scalps, declaring never to make peace with the Mi’kmaq again. It marked the beginning of a guerilla campaign on the part of the Mi’kmaq that lasted several years.84

31 While this guerilla war was taking place in Nova Scotia, some of our leaders continued attending conferences with Panowapskewiyik, Kínipekwiyik, and Massachusetts officials in what is now Maine in an attempt to maintain peace, and of course trade with the English. But when the Kínipekwiyik demanded that Massachusetts stop building new forts and settlements on their land, Massachusetts sent hundreds of troops to the head of the Kínipekw and built a new fort near Nalicowək in the summer of 1754. While this was meant to overawe the Alnôbak, it served only to provoke them into taking action that fall against the new fort on their land.85 The same summer we learned that British authorities were also planning to invade Sikniktuk where the French had built two forts, Beausejour and Gaspereau.86 In order to help defend the forts an unknown number of our warriors gathered in the area, but the expected invasion by the British did not occur that year.

Treaty of 1760 (personal marks)

32 The next summer (1755), our warriors gathered again at Sikniktuk in expectation of an attack. This time British forces successfully took both forts.87 In reaction both to our involvement at Sikniktuk and to the Alnôbakewey hostility in what is now Maine (which Massachusetts had in fact provoked), the governor of Massachusetts declared war (the Sixth Anglo-Wabanaki War, 1755-60) and offered another bounty on the scalps of all Wabanakis. This bounty excluded the Panowapskewiyik who had again tried to maintain peace,88 but it specifically included our people.89 Within days of taking the forts at Sikniktuk, the British sent a force of two thousand soldiers to Menahkwesk where the French had recently built another fort. With only sixty soldiers and 160 Wəlastəkwewi warriors to defend the fort, the French officer in charge ordered the fort to be razed, then withdrew with his forces up the river.90

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

33 The following year (1756), war was officially declared in Europe between France and Britain. Known to the English as the Seven Years’ War or French and Indian War, it saw the start of a concerted campaign on the part of the British to drive the French completely out of North America. Over the next several years major action would occur in places far from our river, from the Ohio valley to Unama’kik (Cape Breton) in Nova Scotia; and once again, parties of our warriors would be directly involved with the French in at least three of these arenas at the same time. In both 1756 and 1757, one group was in the Lake Champlain region,91 and another at Sikniktuk.92 A third group went to what is now Maine93 where the Panowapskewiyik had again attempted to broker peace, but finally had war declared against them after some of their men retaliated for the unprovoked murder of twelve of their people by English scalp hunters.94

34 Later in the war an unknown number of our warriors served at the huge French fort at Louisbourg on Unama’kik,95 which was finally captured by the British in 1758.96 With this loss the tide of war began to turn. British forces under General Jeffery Amherst were now in charge at Louisburg, and they lost no time planning for an invasion of our river. When he finally dispatched two thousand troops in fifteen warships to come to our river, Amherst issued explicit racist orders for them “to destroy the vermin who are settled there,” by which he meant both our people and the Acadians.97 At Menahkwesk the troops disembarked unopposed98 since most of our warriors were away in Panowapskewihkok at the time. The rest of our people who remained at Menahkwesk were mostly women, children, and elders who withdrew upriver immediately upon seeing the size of the British fleet. When our warriors returned from what is now Maine, they began a year-long campaign harassing the British soldiers as they went about building a new fort (Frederick) at Menahkwesk.99

35 British forces successfully captured other French forts at Niagara and in the Champlain valley the same summer, and by September they had even captured Quebec City after nearly a summer-long siege. Again, an unknown number of our warriors participated with the French in defence of that stronghold.100 A month later New England rangers attacked the Alnôbakewey village at St. Francis, killing at least thirty people.101 Meanwhile on our river, ranger parties fanned out upriver that winter from the new Fort Frederick to root out both Acadians and our people. First, they burned the Acadian village at Grimross and in February 1759 they killed and scalped six Acadians at Sitansisk, and burned over 147 of their dwellings and barns.102 That tragic fate would have likely befallen our people had they not fled to Quebec. The soldiers also claim to have destroyed two mass houses, no doubt the one at Sitansisk, and likely also the one in our village at Ekwpahak.103

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12

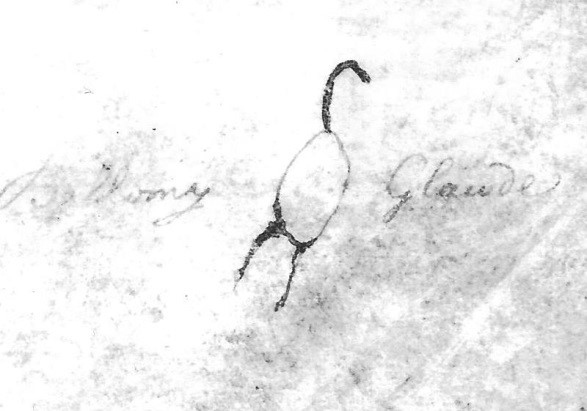

36 In February 1760 a Wəlastəkwew104 named Bellomy Glode was sent with a Peskotomukatewi sakəm to Kjipuktuk to ratify the treaty of 1725.105 Once again there is no record of any negotiations over its terms. The only matters that seem to have been negotiated were the prices of goods and furs and the plans for a system of government-run truck-houses.106 Most importantly, there is no evidence that anyone informed our delegate of the British plan to bring English-speaking settlers to our river, a decades-old plan that was now ready to be put in motion. In fact, an invitation to new settlers was first put out in proclamations published in Massachusetts as early as 12 October 1758,107 just a few months after British forces had landed at Menahkwesk.

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13

The Disposession Begins

37 That our people were never told of this plan to settle our river became evident when a party of men from New England set out for Sitansisk two years later to begin surveying a township in spite of royal instructions issued in 1761108 making it illegal to obtain or be granted land “within or adjacent to the Territories possessed or occupied by the said Indians.” According to an oral recollection published in 1826, the surveyors were about four miles downriver from Sitansisk when

None of these terms, of course, were written into the Treaty of 1760. Since there is no record of negotiations at the treaty table, there is also no evidence that authorities informed our people of their plans, either. As far as Nova Scotia was concerned, the British had become the rightful possessors of our land following the French surrender of Acadia to Great Britain in 1713 since we had supposedly surrendered our land to the French.110 As for the New England surveyors, they headed back downriver but stopped well above Grimross and surveyed a township they hoped to settle later. Considering our response to the New England surveyors, it raises questions as to how other surveys were carried out in this decade, and why there is no record of our objections to them.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14

38 Following the close of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, King George III issued a royal proclamation that was circulated to governors in all British colonies with the threat that anyone violating its terms would be severely punished. One of its most important clauses for our people stated:

Nova Scotia authorities, however, were determined to disregard this portion of the proclamation based on their mistaken assumption that we had surrendered our lands to the French prior to 1713. To stave off any possible resistance on our part, there is evidence that Nova Scotia authorities carefully avoided informing us of the terms of the proclamation. There is also evidence that officials at the Board of Trade in England were never told of Nova Scotia’s violation of the proclamation regarding Indigenous peoples and their lands.112

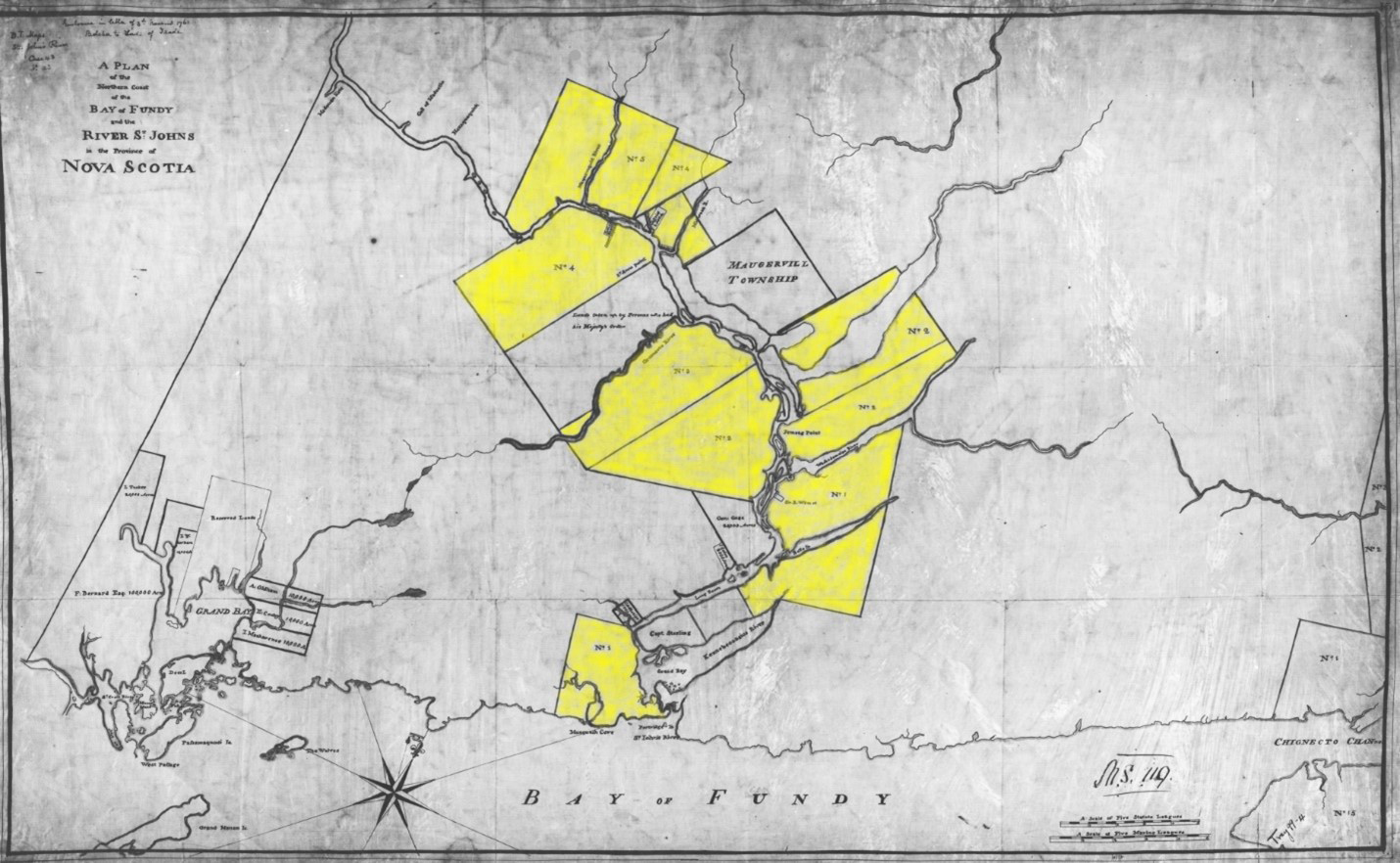

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15

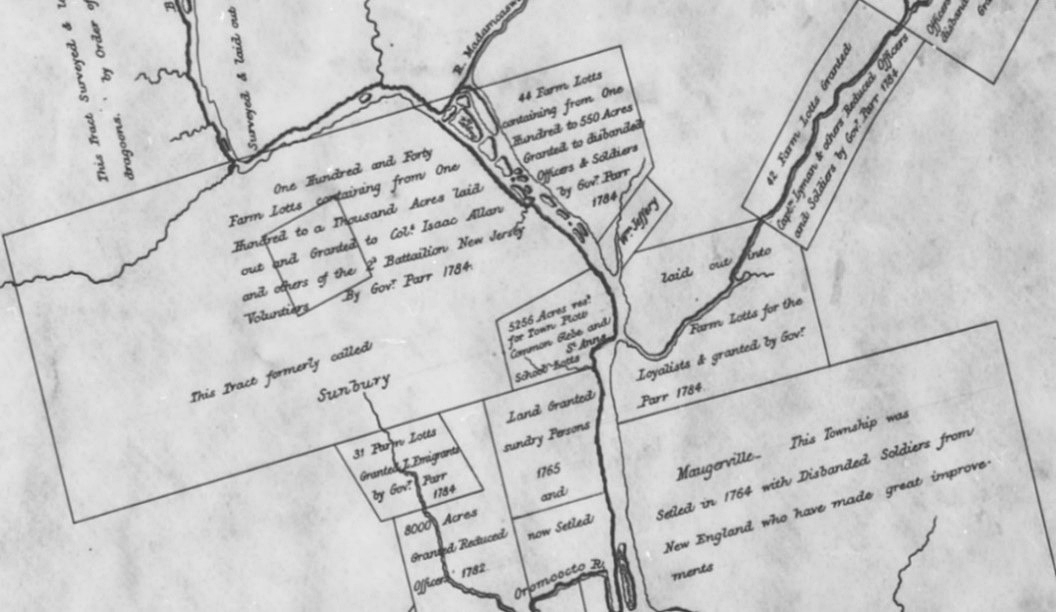

39 Just prior to the publication of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the party of surveyors who had met our people near Sitansisk in 1762 returned to our river with about one hundred New Englanders and literally squatted on the township they had surveyed the year before.113 The new pressures they created on our resources, especially the beaver,114 began affecting our ability to survive so quickly that by 1765 large numbers of our people gathered at the fort at Menahkwesk to protest the encroachments in our hunting territories. When our sakəmak were summoned to Halifax to explain our concerns, the die was already cast. Throngs of petitioners were daily knocking on government doors in Halifax at the very same time, seeking grants of land in Nova Scotia, including our land on the Wəlastəkok, and the government was poised to grant their requests, but not a word of the plan seems to have been disclosed to our sakəmak. Among the petitioners for land was a coterie of wealthy and powerful individuals who had banded together under the name of the St. John River Society. So influential were they that they successfully lobbied to be given first choice of the lands on our river. The society, however, was slow in carrying out its survey, and did not submit maps of the lands it desired until the fall of 1765. Two weeks later in October about a million and a half acres of our land were granted away in what has been called an “orgy of grant-giving,”115 with by far the most and best lands going to the St. John River Society. In the Ekwpahak area the society received nearly all the land. This included the township of Sunbury on the south side of the Wəlastəkw, as well as a township for a mill site on the Nawicowək (Nashwaak River), and a township for Colonel Frederick Haldimand116 and disbanded officers (of the St. John River Society) on the north side. Farther downriver the Society was also granted the choice townships of Gage, Burton, and Conway.117

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16

40 In what appears to have been an afterthought near the end of the granting spree, a meagre 704 acres of our own land were only reserved, not granted to us—including what is now Ekwpahak Island and the mainland on the south side of the river, as well as four acres for our burial ground at Sitansisk.118

Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17

Charles Morris’s report on his survey of 1765 for the St. John River Society contains the following description of our summer village on Ekwpahak Island:

41 Throughout the 1760s our chiefs went to meet with British authorities many times about repeated violations of the treaty of 1760. In 1763 they were in Halifax to complain about the fact that our priest, Father Charles Germain, had been detained at Quebec in 1762.120 Then again in 1765 they journeyed to both Quebec and Halifax to complain about European hunters trespassing in our hunting territories. While Quebec responded with a proclamation reserving to us exclusive rights to hunt beaver unmolested on our lands above Grand Falls,121 no similar action was taken by Nova Scotia to prohibit English hunters on the lower reaches of our river.122

42 In 1767 a priest named Father Charles-Francois Bailly de Messein123 was finally sent to our village at Ekwpahak where he served off and on for three years. His first official acts included a funeral for Nowel Topik (Toubik)124 (Chief Noellobig in English records) at Mehtawtik, and an order for the demolition of the church there since most of our people were now living at Ekwpahak. His record of births, deaths, and marriages at Ekwpahak shows a diverse mixture of Acadians, Peskotomukatewiyik, Panowapskewiyik, Mi’kmaq, and Alnôbakewiyik. Some of these people were residing at Ekwpahak, while others apparently travelled great distances to access Father Bailly’s services. His church records also provide the names of our chiefs at the time, including Piyel (Pierre) Toma,125 who may have been from Ekwpahak, and Apəlowes (Ambrose) St. Aubin,126 who was possibly from Mehtawtik, perhaps even a son of the former sakəm, Nowel Topik.127

43 Other records show that our sakəmak went back to Halifax in 1768 to register more complaints, including more concerns about encroachments into our hunting territories, as well as concerns over the liquor trade, and the recent departure of Father Bailly.128 Although nothing seems to have been done to address these concerns, the Nova Scotia government formally granted us the 704 acres of land at Ekwpahak and Sitansisk that had only been reserved for us in 1765.129 As for Father Bailly, the sakəmak were informed that he would now also have to serve the Mi’kmaq as well as our people.

44 From the time of the visit of our sakəmak to Halifax in 1768 to the start of the American Revolution in 1775, the records of our people are scarce. There is some evidence, however, that we were becoming more and more disturbed by the new English settlers in our territory, including several living in the Ekwpahak area.130 In fact, one Thomas Langan who had been settled about four miles above Sitansisk for six years is said to have been driven off “by Indians.”131 When British troops were sent to Boston from all parts of Nova Scotia in 1768 to deal with the growing unrest leading up to the American Revolution, the settlers on our river became increasingly uneasy. Amidst this unrest some of our people allegedly acted on their extreme dislike of a trader at Grimross and burned down his trading post in February 1771.132 In response, Governor Campbell of Nova Scotia proposed that a blockhouse be built somewhere upriver to “prove a proper check upon the insolence of the savages.”133 This suggests that our people were finally losing patience not only with traders, but also with the bold invasion of our lands by settlers, even if we were still unaware of the enormity of the theft involved in the land grants of 1765. At the very least we saw the influx of settlers as a violation of British treaty promises to accord us with “all marks of favor, protection, and friendship”.

Treaty of 1776, (personal marks)

45 That no priest was provided for us after 1770 was another source of distress considering our strong attachment to Catholicism. To us this too was a serious violation of a treaty promise. Then when British authorities prohibited the sale of guns and ammunition to us at the start of the American Revolution in 1775, we saw it as a huge violation of another treaty promise, not to molest us in our hunting. Since we could no longer hunt without guns and ammunition, this prohibition threatened our very survival.

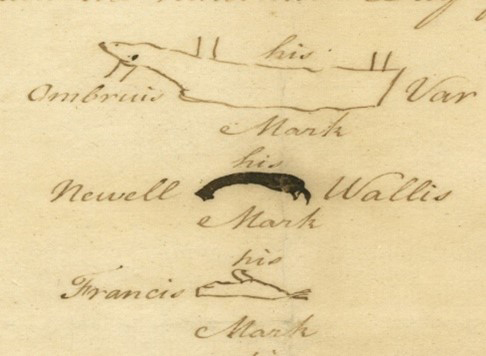

46 In desperation, Sakəmak Apəlowes St. Aubin and Piyel Toma had no choice but to turn to American traders in what is now Bangor, Maine, for guns and ammunition. In return they promised to support the American cause, so fed up were they with British violations of so many treaty promises. The following summer, Sakəm Apəlowes St. Aubin with two others of our people and several Mi’kmaq signed a treaty of alliance with the Americans at Watertown, Massachusetts, just a week after the American Declaration of Independence of 4 July 1776.134 Apəlowes signed that treaty with an image of a bear as his mark, while an English transcriber wrote his name as Ambruis Var [Bear].

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18

47 That fall a number of our warriors joined Apəlowes in an unsuccessful attack on the British Fort Cumberland (formerly the French Fort Beausejour).135 Meanwhile, Sakəm Piyel Toma went to meet with General George Washington who subsequently wrote to thank us for keeping “the chain of friendship,” noting also that some American traders had already established a truck house on our river.136

48 The following summer (1777), an American officer named Colonel John Allan came to meet with our people at Ekwpahak to discuss our alliance with the Americans.137

49 After several days of meetings with Allan, Sakəm Piyel Toma and a few others went aboard a British warship that had come upriver from Menahkwesk.139 It was the first indication of his leanings toward the British. Following the meeting with Allan, Apəlowes and over five hundred of our people, not including Piyel Toma and his family, fled upriver to Mehtawtik and over interior waterways and portage trails to an American post at Machias, in what is now Maine.140 Almost immediately after their arrival, they successfully helped the Americans and Peskotomuhkatiyik to resist an attack by British naval forces.141

50 The next summer (1778), when some of our people started plundering Massachusetts traders at Menahkwesk, we sent a letter to the British officers at the fort there declaring that the river was ours and demanding that they leave. Throughout this period Sakəm Apəlowes St. Aubin had been instrumental in maintaining the alliance with the Americans. Though well on in age,142 he led a flotilla of ninety canoes downriver to attack the fort. On the way, however, they were met by an English trader143 who informed them that a priest and a great supply of gifts had just arrived at Menahkwesk. With this news, Sakəm Toma took charge and called off the expedition.144

51 That September, Sakəm Piyel Toma led a group of our people without Sakəm Apəlowes St. Aubin to the fort at Menahkwesk to receive the promised gifts and the services of the priest. There they were pressed by Indian Agent Michael Francklin145 to blame Allan for the hostilities, to return the stolen goods, and to pay for the damages done to the traders. Before they could receive the sacraments from the priest they were forced to get down on their knees, swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown, and promise no further contact with the Americans.146 These were our obligations as the result of this conference, but there were no recorded reciprocal obligations on the British side, apart from the one-time distribution of supplies and the services of the priest.147 In our tradition of the conference, however, we were accorded a reciprocal promise – the right to camp and cut wood anywhere without asking permission. It is why we referred to this conference as the time we became “all one brother” with the British.148 But this promise was never included in the record of this conference written by Agent Francklin, and there was no formal document signed by both parties as in a normal treaty. The only document signed at the conference was a letter to Colonel Allan declaring our loyalty to the Crown written by the British and signed by Sakəm Piyel Toma and Francois Xavier, who was now listed as second sakəm in the place of Apəlowes St. Aubin.149

52 The next summer (1779), Sakəm Piyel Toma and some of his followers were awarded medals in Halifax for their loyalty to the British.150 A short while later, another grant to the land at Sitansisk and Ekwpahak was issued, this time to Piyel and others, but not including Apəlowes St. Aubin.151 Yet when the British ran out of supplies that fall, Piyel Toma and his followers found themselves seeking supplies once again from Colonel Allan in Peskotomuhkatik, in spite of his promises to the English. After delivering a speech of reconciliation to Allan, Toma and his people spent the winter camped nearby.152

53 By the spring of 1780, just as Allan’s supplies began to run out, Agent Francklin wrote to our sakəmak informing them that supplies had finally arrived for those of our people willing to protect British crews now cutting masts on our river for the King’s navy.153 Desperate for supplies, most of our people went back to the Wəlastəkw to obtain them.154 While there the British orchestrated a huge conference at Ekwpahak, with nine hundred people from many Indigenous nations on the St. Lawrence River155 who demanded that we have nothing more to do with the Americans. Our response was that we would remain neutral “so long as the King of England continued to leave [us] free Liberty of Hunting and fishing and to allow [us] priests for the exercise of [our] religion”156—basically two critically important treaty promises that the British had violated.

54 That summer, both Apəlowes St. Aubin and Piyel Toma and their followers travelled back and forth once more between Col. Allan in Peskotomuhkatik and the British at Menahkwesk. On the British side, the attraction was the priest, and on the American side, it was the possibility that the French, who had come to the aid of the Americans in the war with Britain, might also be able to supply us with a priest. Before leaving for Menahkwesk, Piyel and Apəlowes both assured Allan they would be back and gave him a wampum belt “thirteen Rows Wide, which represent[ed] the Thirteen United States, the Cross at the End their attachment to the French; the other white places the Difft villages of the Indians.” This belt was to be sent to the American Congress and the French ambassador.157

Sovereignty Compromised and Lands Stolen

55 After going to Menahkwesk another time, both Piyel and Apəlowes returned to Peskotomuhkatik for another meeting with Allan,158 but in September, Apəlowes suddenly passed away, some say by poisoning. In a long letter of condolence to our people, Col. Allan shared his deep personal sorrow over Apəlowes’s death.159 He also informed us that our wampum belt had been delivered and that a French priest was finally on his way to serve us.160

56 That winter Sakəm Piyel Toma and his people received regular supplies from the British,161 in return for protecting the mast-cutters.162 Although Allan hoped for a conference with our people the following spring, he was so short of supplies that only a few of our people went to meet him in Peskotomuhkatik 163 to receive the services of the French priest who had finally arrived there.164 At some point that summer, Piyel Toma also died before the customary year of mourning had ended for choosing a replacement for Apəlowes St. Aubin as second sakəm.165

57 With the Americans still severely short of supplies that fall, our people were quick to respond to another British offer of newly arrived “presents” to be distributed at a new British blockhouse, named Fort Hughes, near the mouth of the Welamokətok (Oromocto River). At that meeting, Agent Francklin exploited both our state of want and duress, and our despair at the loss of our leaders by boldly appointing a new head sakəm for our people to replace Piyel Toma, and then allowed our people to choose only a second and third sakəm.166 The only possible explanation for our apparent compliance in this case would have been the demoralization that had accumulated as the result of our constant state of want and duress that culminated in the death of both of our sakəmak. Although the Indian agent did not name his choice of sakəm in his report, it soon became apparent that he had chosen Francois Xavier, the one who had signed the 1776 treaty with the Americans, but who had been named as second sakəm by the British at the conference in 1778.167

58 Difficult as the near century-long period of war had been for our people, the period after the American Revolution would prove to be even more difficult. Where we had always operated on at least a glimmer of hope that we might end up keeping our land and some measure of autonomy and peace during the wars, we had achieved none of these objectives. Ironically, it was the gestures of loyalty to the British by some of our leaders that in the end allowed us to return to our homelands on the Wəlastəkok, but at what price? While we were now without war, our experience in returning to our lands could have hardly been called peace. Within a year of our meeting at Fort Hughes in the fall of 1781, Loyalist settlers started pouring into our land though we had never ceded or surrendered any of it. And within a couple more years as many as eleven thousand settlers had taken our usual hunting, fishing, and planting grounds as far upriver as what is now Woodstock. Even the site of our ancient village at Mehtawtik and the land granted to us for our village at Ekwpahak were now granted away. It was nothing short of theft on a massive scale.

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19

To comment on this article, please write to editorjnbs@stu.ca. Veuillez transmettre vos commentaires sur cet article à editorjnbs@stu.ca.