Research Note

The Economic Exploitation of the Black Refugee Settlement at Loch Lomond, New Brunswick, 1836-1839

1 Although William A. Spray assembled considerable details about the community of Black Refugees who settled on lands near Loch Lomond in New Brunswick after the War of 1812, the story of the Black settlement near Saint John is still to be told. Spray highlighted the attitudes and benign neglect exhibited by the provincial and local authorities in addressing the needs and security of the escaped slaves who had settled in a new land.1

2 However, new analysis of land registry records combined with colonial government documents reveals a higher level of blatant exploitation of the original Loch Lomond settlers and their descendants. From 1816 when it was suggested lands should be assigned Black Refugees in Loch Lomond, aside from a few exceptions, the recipients for the African Settlement were never shown the same degree of concern afforded new White immigrants to the colony.2 While colonial authorities ignored the pleas from Black Refugee families, White merchants in Saint John and Simonds Parish, along with other timberland speculators, used the twenty-year delay from 1816 to 1837 to convince provincial officials that they deserved a portion of the Loch Lomond grants intended for the Black Refugees.

3 Whereas standard policy towards new settlers seeking land grants resulted in 100 acre lots being assigned to them, as well as an extra fifty acres for the spouse and each child, the Black Refugees were offered only fifty-five acres in total. Usually, a license of occupation would be issued upon a decision by the Surveyor General’s Office to approve a land petition from the individual or group.3 The license was in place for up to three years or until the occupant had demonstrated physical improvements to the land such as shelter, a garden, domestic animals, or cultivation. Thereupon, a deputy surveyor was instructed to formalize a survey and the land grant was issued to the settler.

4 Although licenses of occupation were issued from Fredericton for Black settlers and their families, many were not converted to land grants over the next twenty years. Although some licenses were renewed, the major stumbling block was the insistence by the colonial authorities that each Black settler would be responsible for all survey costs which was not typical for White settlers.4 Considering that most of the Black Refugees throughout the 1810s and 1820s could barely subsist on the rocky inarable lands and often sought work in the city to survive, it is not surprising that the majority would not accumulate the capital necessary to complete the final survey to receive ownership of the lots.

5 Spray has shown how many settlers barely survived on supplies and food provided by colonial officials from 1816 to 1835. Repeatedly, individual Black settlers and their families petitioned the authorities for supplies, farm implements and seed to make it through the coming winter season. As late as 1833, the Justices of the Peace for the City and County of Saint John pleaded with the Legislature to be reimbursed for expenses incurred in “support of the aged, infirm and distressed black refugees.”5

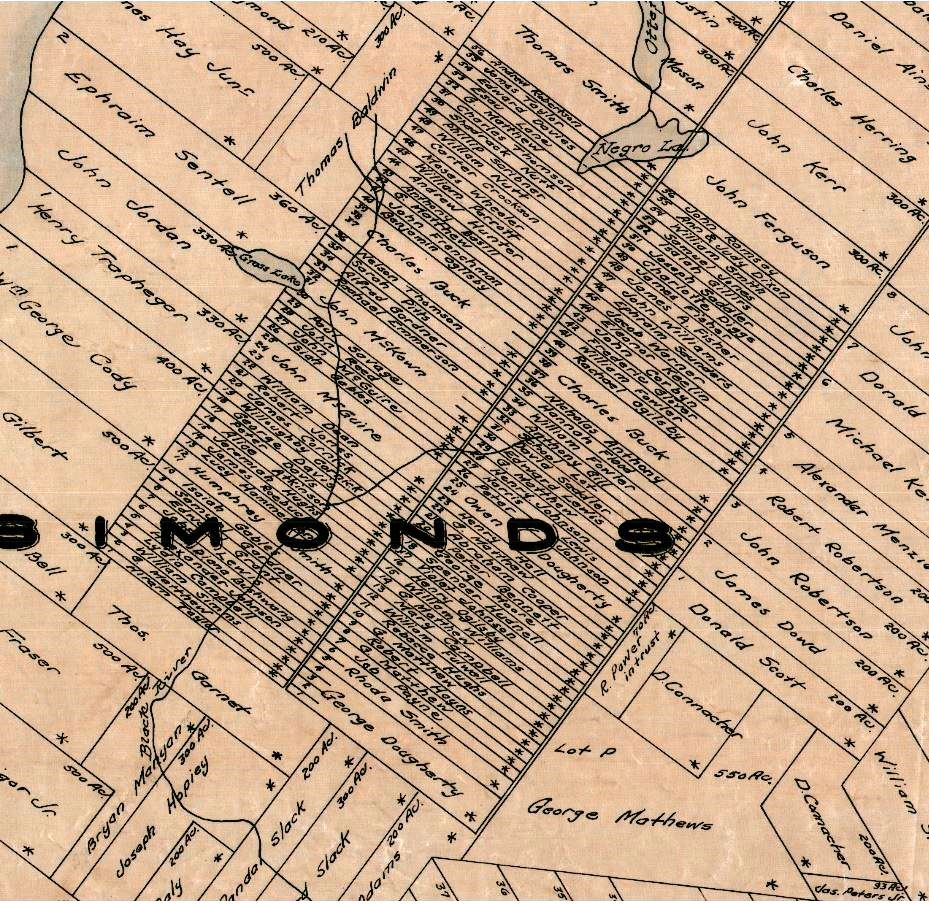

6 In 1836, a Committee of the House of Assembly finally recommended that each Black settler receive a fifty-five-acre grant in the “Black Refugee Tract” spread across 112 lots. However, over the course of the previous twenty years several White settlers had already been issued grants to some of the tract. Some of the reasons given for this action by the offices of the Provincial Secretary and Surveyor General were based upon the expiry of some licenses of occupation for Black Refugees who had not made improvements or had moved elsewhere, likely into the city or out of the colony.6

7 A closer examination of the new White grantees, who included Charles Buck, Humphrey Smith, George Matthew, John McKown, George Dougherty, and John McGuire is revealing. They had secured permanent titles to over 1050 acres out of a total of 6160 acres originally set aside for Black Refugees and their families.7 When the tract of land was finally approved on 4 September 1837, a total of seventy-four refugees received final title to their properties. As Spray observed: “Probably no other group of immigrants who attempted to establish themselves in New Brunswick ever had such a difficult time to obtain land.”8

8 But that was not the worst impediment to confront the Black settlers in their efforts to eke out an existence near Loch Lomond and develop the community of Willow Grove. Of the six original White grantees to receive lots before 1837, George Matthew’s father, George Sr., was approved for 385 acres in the Black Settlement in 1817.9 He recognized the valuable location at the mouth of the river for mill privileges and potential for shipbuilding.

9 Harvey Amani Whitfield argues convincingly that Black refugees were viewed in Nova Scotia in the same light as the Black Loyalist slaves arriving after the American Revolution and not as free slaves.10 Furthermore, colonial officials and the general public looked upon Black Refugees them as cheap labour for the expanding economy. Like Nova Scotia, New Brunswick residents racialized Black Refugees as a source of cheap labour for the colony’s expanding economy.11

10 George Matthew’s approach to the Black settlers at Loch Lomond seems to have followed this pattern. Although he appeared to be sympathetic to their hardships and concerns, it did not deter him from taking advantage of a business opportunity. George, the son of Capt. George Matthew Sr. of Saint John, was born there about 1795. His father became highly successful as a mariner and eventually chief Harbour Master for the port. This gained him many influential friends and allies in the political circles of the city and colony. George Jr. followed in his footsteps as a merchant in Saint John and an investor in a sawmill operation on the Black River.

11 As a consequence, he hoped to acquire suitable timberlands to expand his mill and land upon which to accumulate assets and capital. Likewise, Matthew used his political ties to receive political appointments at the local county level that would benefit his business objectives.12

12 Following the arrival of the Black refugees and the appointment in 1816 of Judge Ward Chipman to investigate and report back on the possibility of settling the refugees on lands near Loch Lomond, the current White land owners in the parish were consulted. The final report delivered to Provincial Secretary William F. Odell in November, 1816, reflected positive feedback from the landowners who viewed the new arrivals as a cheap labour force. Included among these owners was George Matthew who owned over 700 acres near the proposed settlement.13

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

13 By 31 January 1817, George Matthew Senior was granted lots 39 and 40 totaling 385 acres situated along the Black River area bordering on the “Black Settlement” and extending to the Bay of Fundy. Ideal for anyone with mill operations, this may be when his son saw the opportunity to pursue timber operations and strategically acquire any lands which flowed into the tributaries of the Black River. Following his father’s death, his mother, Jane, conveyed these holdings to George Jr. in December 1838.14

14 Other White landowners in the vicinity began to apply for more land inside the refugee tract. Between 1817 and 1833, another 750 acres were granted to Humphrey Smith, John McKown, Charles Buck, George Dougherty, and John McGuire. This was during the period when licenses of occupation were already assigned to Black Refugees anticipating confirmation of permanent title. That also included fifty acres to be set aside for a school lot. The original tract of land for the Refugees had been diminished by fifteen parcels out of the 112 lots. The land grants received by the White owners would have been chosen for best prospects for arable land and available timber.15

15 For the Black Refugees, land settlement and cultivation to meet the requirements of a licence of occupation were practically insurmountable without other sources of capital. Graeme Wynn offers some insight into the costs of settlement. Typically, a land petitioner would receive a 100-acre forested lot plus fifty acres extra per child. In this instance, the Black Refugees were allowed only fifty-five acres and no additional allowances. Within a three-year period, each settler was expected to clear and put under cultivation three acres of every fifty acres granted.16 Not counting the cost of necessary implements and seed, the Black Refugees were hard pressed to meet these minimal requirements.

16 Furthermore, these improvements to the grants does not include the costs of labour to erect a basic log cabin with chimney, cellar, and shingled roof, let alone the more expensive framed house. Wynn estimates that even with help from friends and neighbours, the cost to erect a house was between £3 and £5 in 1840. Adding the need for a cow or other farm stock, the average cost to establish themselves rose to £30 to £40 in total during the 1830s and 1840s.17

17 By the mid-1830s New Brunswick was experiencing an economic boom in investment and the growth of sawmills. George Matthew was part of that expansion in the timber colony. Like other Saint John merchants, he had accumulated timber rights and invested in existing mill properties in St. John and Charlotte Counties. Particularly between 1826 and 1832, Matthew aggressively acquired timberland and mill privileges throughout the two counties.18 Expansion of his holdings and consolidation of his presence on the Black River near the “African Settlement” was an obvious business decision.19

18 In this pre-census period before 1851, one can only gather limited details about the original occupations of the Black Refugees. Moreover, the bureaucratic procrastination that stalled efforts to secure their land grants, makes it difficult to analyze the motives of those Black settlers who persisted on the land and those driven to find other options in Saint John and sell or lease their 55-acre grants. Some were drawn back to Loch Lomond from the city each Spring which affirms the sense of place they had developed for the Willow Grove area.

19 Spray asserts that whereas the majority of Black Refugees came originally from the southern states to settle in an inhospitable climate, that they were not able to adapt due to the numerous obstacles that colonial officials placed in their path. However, while some settlers described themselves in a petition to the House of Assembly in 1828 as unable to adjust to the new environment due in part to “their circumscribed ability,” others were not so quick to label themselves in such a manner.20

20 As early as 1822, many Black residents who still only had licences of occupation, protested the efforts to reassign lands in the Black Settlement on the pretense that the original grantees had not fulfilled their commitments to improve the properties. This practice of escheatment on “unoccupied” land was disputed by the Surveyor General to the House Committee, but that did not deter interlopers from trying. During the summer of 1824, the St. John Globe reported the Blacks in Loch Lomond had protested these intrusions to the Legislative Assembly and attempted to physically bar them from their lands. To that end “a number of females” took matters into their own hands and were accused of threatening a White man and his wife.21

21 The grievances by the Willow Grove residents went unheard until September when Charles Buck, a White occupant, was refused aid by the Executive Council for actions taken by the protesters against his property. However, local county authorities chose to arrest ten Blacks for assault from the June incident and another thirteen were charged with rioting, and seven with acts of arson in September 1824. Although the arson charges were dropped, the activists still received seven to ten days in jail. Over the next three years, further protests were reported to the House culminating in the arrest of three Black women in September, 1827, for unlawful assembly and assault. County records do not report on the outcome of their cases or reveal their names. Those women who seem to have spearheaded protests in the community may have stepped in to fill a leadership vacuum left by their husbands and relatives trying to eke out a livelihood in the city.22

22 In an effort to draw Black settlers away from the city and back to a sustained livelihood in Willow Grove, a group of forty-two men and women residents appealed to the Lieutenant Governor and Council in 1828 to support the construction and operation of an oatmeal and flouring mill. A grist mill, they felt, was the lifeblood of the settlement that would guarantee continued prosperity and reduce the temptation for “the unsteady amongst their number” to seek a living in the city where the nearest mill was located. Apparently, the Black citizens had reached agreement with Thomas Garnet, a recent English immigrant, to share his knowledge and skills in operating a grist mill in the settlement.23

23 What is extraordinary about these three years of agitation is that it was entirely unnecessary, since Lieutenant Governor Sir Howard Douglas had already accepted a recommendation from the Crown Land Office to confirm fifty-acre grants for the Black settlers. Unbelievably, this approval was not communicated to the local people over that period. Community activists had faced the intrusions on their rightful lands with little or no support shown by colonial authorities.

24 Spray concedes that the Black Settlement did not grow substantially in the 1830s even with support from the county Overseers of the Poor. As a consequence, it did not prosper and many of the original land grants confirmed in 1836–37 passed to White settlers. But the examination of land registry transfers in this crucial period offers an explanation for the rapid decline of the Black Settlement based on sheer exploitation by White landowners and timber merchants.

25 A thorough review of the land registry records for Portland/Simonds Parish in St. John County from 1837 to 1840 reveals an astounding discovery. By cross-referencing the buyers and sellers of lands in the tract set aside for the seventy-four Black settlers and six White landowners, a pattern emerges that can only be described as a form of economic racism. This was perpetrated in a systematic manner by George Matthew and his strategy to control the land and timber resources found within the Black Settlement.

26 Beginning within one month of the issuing of the land grants in September 1837 to the refugees, Matthew undertook a concerted effort to buy or lease- where he could not buy- the individual allotments of fifty-five-acre parcels. Between October 1837 and August 1838, George Matthew signed transfer deeds or leases with many of the Black grantors. Out of seventy-four owners of grants, he acquired rights to sixty-four or over 85 percent of the original Crown grants to the Black Refugees. Where lots were fifty-five acres, his purchase price ranged between £3 and £20 with the average price closer to five pounds. Leasing of timberland on the property was consistently negotiated for £5 per parcel. In these instances, one does not know from available documentation why Matthew chose the lease option. Perhaps the owner refused to sell, or the land did not meet his needs for potential cultivation. Later transactions reveal that a few Black owners who started out leasing eventually sold to him.24

27 Matthew did not stop at just purchasing the lands of Black settlers within the original grant of 1837. In the same period, he consolidated his holdings by buying the grants given to White settlers Charles Buck, John McGuire, and George Doherty. By 1839 this added at least another 850 acres to his holdings.25 Registry office documents also reveal the movements of many Black settlers who, in the intervening years, were compelled to move to Saint John to eke out an existence. In other cases, some petitioners among the Black refugees who arrived in 1816 had died or moved out of the colony. Deeds indicate that surviving widows and children were the sellers of some lots.26

28 Matthew certainly recognized this state of disparity among the settlers. As early as December 1839, he had assessed that eight lots comprising 400 more acres appeared to be abandoned or without necessary improvements and applied to the Surveyor General to have those lands escheated and formally granted to him.27 Indirectly, he consolidated other lots in the Black Settlement for himself even though they had been previously sold. This was the case when he purchased the holdings of Ephraim, Robert, and Jehiel Sentill, local farmers, who bought the original grants of Hiram Taylor, Spencer Hudland, and William Nutt during the same 1837–38 period.28

29 What is most striking about the relationship between Matthew and the Black Refugees is his acceptance of the status and treatment of them as perceived former slaves or potential cheap labour. Overwhelmingly, the transfer of land titles, leases and assignments as an agent commonly state the name of the seller/buyer, occupation, and residency. In almost every case, the documents which would invariably be prepared for signature and witnessed by George Matthew recorded him as a merchant or millowner. For many of the Black sellers who could not write, Matthew, while citing their names usually without an occupation - not even farmer or labourer - clearly bracketed the words “colored person, man or woman” after their name; a practice found more commonly in land records and petitions but not in deed transfers.29

30 Furthermore, after combing through thousands of land transactions over the past few decades in county registry offices, it becomes evident that George Matthew prepared the most basic of documents for Black Refugees. The vast majority of Black settlers could not read or write. Aside from a legally witnessed format, Matthew would have realized the deed or lease was a simplified version of most standard legal documents. For example, the lease from Alice Atkinson, simply states:

31 Compare this previous format to the commonly worded legal transfer document from James Millican to George Matthew in 1839:

32 This opening statement is then followed by an extensive description of the property followed by the closing paragraph: “together with all and singular buildings, erections, and improvements in and upon the said last described lot of land standing and being and the rights, members, privileges and appurtenances thereunto belonging or in anywise appertaining. To have and To Hold the said tract of land and premises…”32

33 All thirty-three leases were formatted like the first example which left Matthew with broad powers and no schedule or term for a lease. Furthermore, he often executed leases and deeds on the same day. On 24 April 1838, Matthew transacted ten leases; on the 25th; another five. It is obvious that this was done strategically and expeditiously to gain control of as much land and timber as possible closest to his mill operations on the Black River. In addition, on many of the same dates, he purchased outright the lots of other grantees in the settlement.33 By the end of 1838 Matthew had amassed close to 4000 of the 6160 acres in the Black Settlement. Moreover, he had strategically purchased another 1200 acres adjoining the settlement along the courses of the Black River to its mouth that emptied into the Bay of Fundy.

34 What is not revealed in the documents is whether he employed any of the Black residents in timber cutting or milling. Certainly, he would have had a close familiarity with the refugee family members through his activities as an Overseer of the Poor and Commissioner of Roads. Did he use this influence to secure buy/sale agreements in 1837–38 ahead of other competition? Would residents have felt obligated to sell to Matthew knowing it might mean their survival through the coming winter? At the time of these transactions, twelve original grantees lived in Saint John and one in Fredericton, primarily to earn a living.34 There is no indication that Matthew ever employed any of the Black Refugees in his timber or milling operations.

35 George Matthew was not the only individual to exploit the timber resources in and around Loch Lomond. But he was the one merchant and mill operator to attain a level of monopoly over the land of the original residents in the African Settlement that would undermine their development as a community. His control of land and leasing of timber rights along the tributaries of the Black River and Mispec Stream that reached into the heart of the Black Refugee tract made it impossible for them to succeed. Judging by the population of the Black families still residing in the area in the 1851 census, there were no more than fourteen family names out of the seventy-four grantees in 1837.

36 George Matthew, from an influential Saint John merchant family, used his county appointments and access to colonial administrators to influence land policy and simultaneously foster trust among the Black settlers when they needed essential support for supplies to survive the poor economic times. But this came at a price, which positioned Matthew and other White speculators to convince the majority of Black grantees between 1836 and 1839 to sell or lease the only valuable asset that they possessed in the colony.

37 Further research may reveal how these families responded to their plight and how they sustained themselves throughout the coming decades to establish a distinctive identity at Willow Grove.