1 This Research Note explores mourning rituals of the Victorian era and examines the comfort and sympathy these practices brought to some late-nineteenth-century New Brunswickers. These rituals were alive and well in the province, as seen through the multitude of items related to mourning discovered across New Brunswick museums and personal collections. This Research Note will explore three of these mourning dresses, as well as several artefacts of mourning from New Brunswick museums, to shed light on this cultural practice. As Valerie Evans notes, the vast lots of mourning items donated to Canadian museums exemplifies the omnipresence of these traditions in this country.1 This research analyzes the specific Victorian mourning rituals that were present in Anglophone New Brunswick, with brief mention of Francophone rituals. Many museums across New Brunswick hold visual and material cultural artefacts relating to mourning and there have been several exhibitions on the subject. There is, however, a paucity of academic research on the history of mourning in the Maritimes which this Research Note will address.

2 Dress historian Lou Taylor argues that in the years 1850-1890 “Mourning became such a cult that hardly anyone dared defy it.”2 This study explores Victorian mourning rituals and customs, combined with specific case studies to create a holistic picture of mourning in New Brunswick during the late nineteenth century. As my research analyzes visual and material culture from New Brunswick between 1865 and 1890, the viewpoint for this study will be largely Anglophone with some mention of Francophone traditions. It is important to acknowledge, however, that New Brunswick is the land of the Mi’gmag, Peskotomuhkati, and Wolastoqiyik peoples. Although their mourning practices are not discussed here, we must consider the impact that European settlers had on the Indigenous peoples of the region and acknowledge that this Research Note only examines a specific culture from a wide array of cultures and rituals that were present in New Brunswick in the late nineteenth century.

3 Many English settlers in late-nineteenth-century New Brunswick would have followed their ancestors, family traditions, and cultures for proper mourning etiquette. As Catherine Lucas and Phillis Cunnington in Costumes for Births, Marriages, and Death explain, a “Victorian vogue for mourning”3 was present at this time and this can be applied to a New Brunswick context. Those in New Brunswick, largely from Great Britain and the region surrounding it, would have looked to English customs to learn mourning rituals, just as they were exploring British fashion to assess the latest styles.

4 When beginning this research, I visited several small museums and collections in the Southeastern New Brunswick region. These included the Albert County Museum, Keillor House Museum, and Boultenhouse Museum where the curators were welcoming and excited to hear about my research. These museums provide important primary evidence of mourning customs that allow research such as this to be conducted. The Keillor House Museum as well as the Boutlenhouse Museum are house museums, whereas the Albert County Museum is spread across several buildings that used to make up the “shiretown” of Hopewell Cape. These museums offer an insight into the historic communities in which they are located.

5 Mourning practices varied slightly depending on the region or the cultural community in New Brunswick, but even the smallest museum collections reveal that these rituals were being practiced in a similar fashion to the rituals in Victorian Britain. During the late nineteenth century middle-class New Brunswickers would have heard of the passing of a friend or relative through the ritual of mourning calling cards, like the one pictured in figure 1. Another method used to reveal the death of a loved one was to “make a big black bow with a long wide ribbon, three or our inches wide. It was then attached to the door.”4 New Brunswick museums preserving artefacts such as these mourning calling cards allow us to further investigate these traditions.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Full Mourning Costume

6 The early period of grief, as directed by Victorian rituals, is called full mourning. This stage usually lasted for a year, during which the bereaved wore an ensemble of full black. During this period, women were encouraged to wear a black dress, a veil, and a bonnet.5 Likewise, women were encouraged to trim their costumes with crepe fabric, which differentiated a mourner from the average person wearing black (a growing fashion).6 The texture of the material worn during this period was almost equally as important as the colour itself. During full mourning, widows used fabrics with a matte texture such as bombazine and crepe, this can be seen practiced in New Brunswick [fig. 2]. Likewise, during this stage, widows were not to wear jewellery unless it was commemorative or jet jewellery. Gold jewellery was not to be worn.7 Every small detail of costume during full mourning had to show grief and women even matched their undergarments to their stage of mourning.8 Furthermore, many women and men used handkerchiefs trimmed with black to signify mourning. As time passed, the width of the black border on the handkerchief lessened in conjunction with the extent of crepe used in costume.9

7 Because mourning dresses were so precisely made and often matched the fashion of the time, there are many mourning dresses still intact across New Brunswick. Unlike other garments which were often repaired, sold, or repurposed, mourning dresses were usually tucked away in a closet or chest after the full mourning period ended.10 With rising popularity in mourning warehouses globally, it was often advertised that keeping crepe in the house when not in mourning was unlucky; meaning that mourning dresses were rarely reused or repurposed unless they were directly sold to another widow.11

8 This mourning dress [fig. 2], housed at the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John, was originally worn by Jessie Cameron Kupkey from Perth-Andover, New Brunswick. She used the dress to mourn her eldest child, Isabella, in August of 1884. Isabella tragically passed at the age of three months. She used the same dress for the mourning of her father-in-law, John J. Kupkey, who passed away in March of the same year.12 There is little further information about the Kupkeys, but it can be assumed that this family was relatively affluent since Mrs. Kupkey could afford to go into full mourning for her father and child. This dress closely reflects the fashion of the time. In the 1880s, women’s wear often featured a tightly fitted bodice and an emphasis on the bustle at the back of the skirt. Women’s dresses frequently included a flounce around the neckline and wrists, these were often done in white, as in this dress. The neckline in these dresses was high, and the sleeves were narrow.13

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

9 Middle-class women in New Brunswick were closely reflecting the styles of the time, both in mourning and regular wear. This practice illustrates that by adopting these leading fashion styles, New Brunswick was indeed part of the British Empire.

10 These trends were not uncommon in New Brunswick. Another mourning dress from the same period is housed at the Albert County Museum. According to didactics in the Albert County Museum, this dress [fig. 3] would have been worn for six months, followed by purple for three months, and green for the remaining three months.14 This timeline is likely for a family member other than a husband, as the practice of committing to full mourning for at least a year was well established during the nineteenth century throughout the British Empire. It is possible though that these traditions would have varied in rural areas of New Brunswick where specialty fabrics were not as widely available or affordable. Interestingly, this dress uses materials that are unlike typical mourning dresses with the elaborate trim at the bottom of the bodice.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

11 The Albert County Museum also has a shawl [fig. 4] placed next to the mourning dress. These shawls, although often more subdued, were a common part of mourning outerwear.15 The shawl is shimmery—featuring elaborate beading—which is unusual for mourning wear but could be worn at a later period of mourning.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

12 These items of full mourning prove that these practices inherited from Victorian society were present in New Brunswick during the late nineteenth century. These elements of fashion, owned and worn by New Brunswick women, exemplify not only the way that women grieved but also prove that—in times of trouble—we turn to rituals. These collections in museums across New Brunswick also illustrate that some settlers were bringing traditions from Victorian England to Canada.

Half Mourning Costume

13 After the period of full mourning, usually for a year and one day, came a period of half mourning where the rules and regulations for the dress code were relaxed. This period began by fully omitting the crepe and replacing it with a black ribbon. This often lasted for three months.16 After this, softer colours such as lilac, grey, and white, were worn by widows with the softer black ribbon.17 Half mourning could last anywhere from six months to life.

14 This dress [fig. 5] from the New Brunswick Museum has no provenance. It appears to date from about 1865. The moiré silk, in lavender, along with the black velvet edging indicates it was a mourning dress. This dress, because of its style and materials, most likely came from an upper-class New Brunswick family.18

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

15 The use of a lilac or lavender colour was suited to the later stages of mourning. The black velvet, as it is a relatively matte material, shows respect for the deceased through the sombre edging. This dress shows that even as mourning practices were reaching their height in Great Britain, during the 1860s,19 these styles were already prevalent in settler New Brunswick. The dress compared to others of the period is relatively understated in design with minimal extravagant details. Interestingly, there is a touch of lace along the bodice, an uncommon fabric for mourning, but likely would have been accepted at this later period of mourning.20 The dress, like many in the 1860s, features a tight bodice, buttoned front, and high neck. Beginning in 1865 the skirt of dresses began to be fuller in the back (rather than the previously preferred bell-shaped skirts). White lace was largely popular during this period (although black is used here) and large satin bows were making their way into the mainstream.21

16 Although there is little information on the origins of the half-mourning dress [fig. 5], the fact that it has ended up in the New Brunswick Museum shows that these rituals were being practised in the province. Unfortunately, because many half-mourning dresses could be modified and used again for another purpose (unlike the crepe and bombazine of full mourning clothing), there are fewer New Brunswick examples of half-mourning dresses in good condition. This half-mourning dress (in contrast to the full mourning dresses which were readily available in almost all museums I contacted) is one of the few in New Brunswick.

Children’s Mourning Practices & Dress

How clay cold now these once warm lips

Which mine so oft have prest

And silent is that prattling tongue

In everlasting rest

17 This poem from a cross-stitched sampler, done by a twelve-year-old girl to memorialize the death of her brother, shows just how prevalent death was in the lives of young ones during the nineteenth century. According to dress historian Lou Taylor, children who had lost a parent often formally mourned for twelve months.23 In some cases, however, children wore white clothing with black trim, instead of the full-black ensemble. Children, like poorer adults, would often have their old clothes dyed to become mourning clothes. Children usually mourned only for the closest of relatives and mourned generally in similar ways to that of the adults around them.24

18 This dress at the Keillor House Museum [fig. 6] is the mourning dress of a child in the 1890s. It comes from the Gunningsville region of New Brunswick. The fact that this family could afford to put their child in mourning clothes shows that they were likely relatively well-off. Besides this information there is nothing further on the origins of the dress. The dress is an A-line silhouette and features puffed sleeves. It is done up with hook and eye clasps in the back and has a small belt-like loop that goes around the waist of half the dress. There is a collar on both the front and the back. The dress is more poignant when compared to the larger and elegant mourning dresses that older women would have worn at the time.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

19The fact that even the youngest in society were participating (or forced to participate) in mourning rituals shows the extent to which these British traditions were making their way into parts of New Brunswick society. Mourning rituals have continually acted as ways to bring comfort to the living and respect to the dead by signalling to the community personal sorrow and that one was paying their dues.

Mourning Accessories

20 Of course, these mourning traditions touched more than just the dress. These fashion trends extended into the homes and hobbies of widows. One form of memorialization for the dead included hair wreaths, often designed and woven by widows and other family members. These hair wreaths came to symbolize the deceased25 and, as hair is one of the few body parts that does not disintegrate over time, represented a continued existence of the body to which it once belonged.26 Hair wreaths, which could be made from one specific person’s hair, or a combination of an entire family’s or community’s hair, were popular in the Americas from the 1780s onwards. These handmade memento mori were distinct from an increasingly commercial world.27 Creating hair wreaths—some of which included photos— represented the social and emotional life of the deceased, and these designs spoke to the personality of the deceased.28 This tradition was extended to both Anglophone and Francophone communities in the Maritimes.29

21 An important part of mourning rituals in Victorian culture was the use of memento mori to reflect loss and remind oneself of the death of a loved one. A memento mori is an object that serves as a reminder of death and comes from Latin, meaning “remember you must die”. Memento mori—often skulls and other more direct symbols of death—also included hair relics and jewellery during this time. Hair memento mori, hair relics, and hair jewellery were all widely popular as part of mourning rituals in Victorian society. Hair jewellery came in many forms, from bracelets made with braids of hair to lockets that contained a lock of hair. Hair relics, or hair memento mori, as previously discussed, were essentially a wreath of human hair. The hair often came from a deceased person or several deceased people. As the trend in these hair relics grew, though, many small communities, families, and groups began making these relics to mark important occasions and or simply to have a reason to get together.30

22 During this research I encountered two examples of hair relics/wreaths in New Brunswick museums. The first one [fig. 7] comes from the Keillor House Museum and is an example of a mourning relic. Conversely the hair wreath from the Albert County Museum [fig. 8] was likely made for a community event. There are many different types of hair featured in this and the use of turquoise beads makes it much less sombre than the one from the Keillor House. The hair in these wreaths is woven into small flowers, with small bits of wire holding them together. The detail that goes into these is astounding. These wreaths show the love and care of memorialization.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

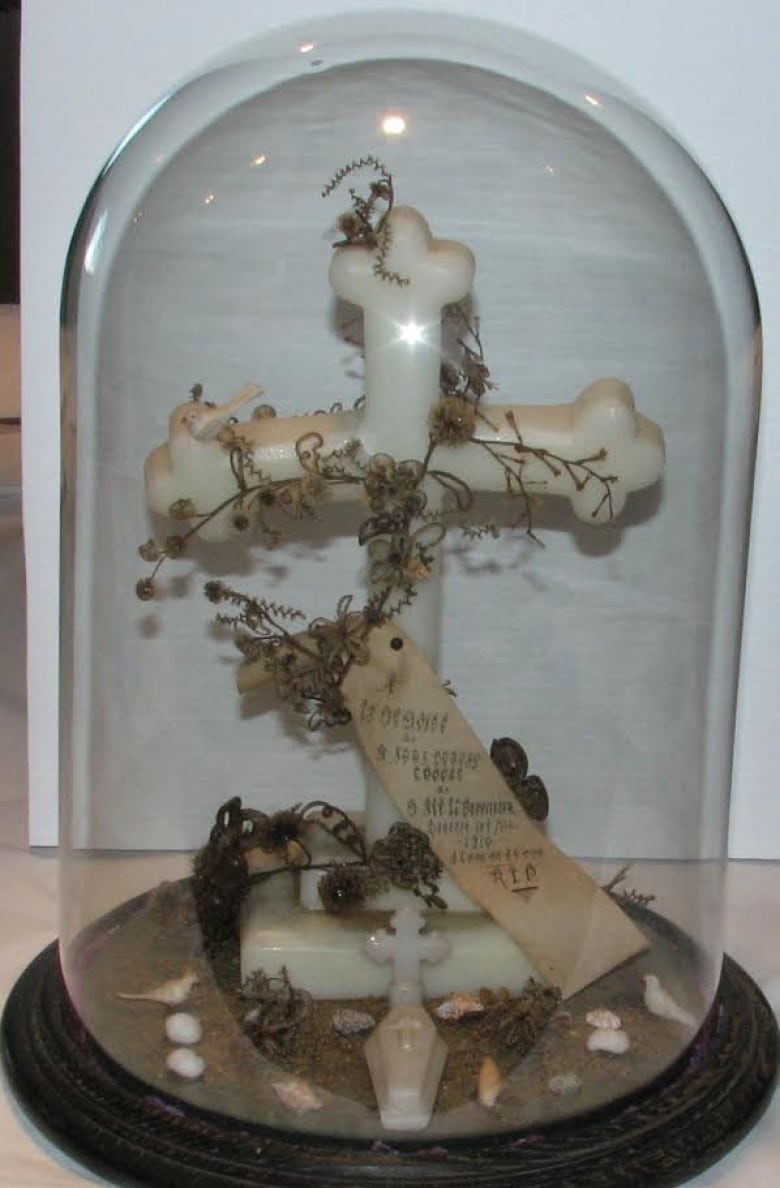

23 This practice was not only prevalent with English settlers in New Brunswick, though. There are several examples of hair wreaths, crochet, and jewellery coming from Acadian communities as well. This hair memento mori [fig. 9] comes from Caraquet and features the hair of over two dozen deceased family members.31 The hair wrapping around the cross exemplifies the religious aspects of mourning rituals.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

24 My grandmother owns a hair wreath, which was one of the many items that inspired this research [fig. 10]. This hair wreath has been passed down by family members from the Albert County region of New Brunswick. The wreath, to her knowledge, is comprised of hair from various family members. It was likely made by her mother’s aunts, which dates the hair wreath to the late nineteenth century. She believes that it was made by one of the family members while they were all still alive. This practice was prevalent both to mourn the deceased as well as a symbolic representation of a community or family.32 My grandmother believes that hers was the latter. She knows little about it but is aware of the contemporary interest and value placed on this fascinating aspect of Victorian society.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

25 Jewellery also played an important part in memorializing the dead. During the later periods of mourning, widows were socially permitted to slowly add jewellery back into their dress.33 Mourning jewellery was often made of bog oak, jet, or (later) black glass.34 Sentimental jewellery was also quite popular, with widows wearing mourning jewellery that included locks of hair or photos of the deceased.35 Mourning jewellery traditions developed in England from other countries such as Germany during the eighteenth century and these traditions were firmly held during the nineteenth century as well.36 These customs were also adopted in New Brunswick. Many chose to wear jewellery that the deceased had bequeathed to them for the later stages of mourning.37 These jewellery memento mori were visible symbols of remembrance. Many of these pieces had small inscriptions: often, “In remembrance of.”38

26 This particular mourning accessory [fig. 11] comes the Keillor House Museum. It is a brooch with a climbing ivy-like gold border. Ivy, during this period, symbolized immortality. The brooch, largely jet black, features an inscription that reads “in memory of.” This shows that even minute details of Victorian mourning—such as mourning accessories—were prevalent in New Brunswick. Although there is no specific date associated with the brooch, the Keillor House archives date it to the mid-1850s.39 There is a small cross on the left side of the brooch that ties this practice to religion and the afterlife. Additionally, there is a small photo of the deceased in the middle that suggests it comes from a middle- or upper-class family that would have had the funds and access to photography during this period.40

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

27 These mourning accessories exemplify the thought and care that went into mourning rituals in the British Empire. Both English and French settlers partook in these practices to some extent and found comfort and relief through modified rituals of mourning. The way that these small accessories and craft pieces memorialize the dead would have provided comfort and led the community to rally around the family of the deceased and demonstrates just how important these small acts of remembrance were.

Conclusion

28 Victorian mourning rituals—as with many rituals from Victorian society—may not have been practised as closely or as strictly as they seem to have been historicized. It is necessary to consider whether these histories were prescriptive or descriptive. They were, though, clearly practised to a certain extent and spread throughout the British Empire during the late nineteenth century. Through my research, it has become evident that many of these rituals were customary in settler New Brunswick.

29 Although the items presented in this research vary from different periods and locales in New Brunswick, there is a clear link between Victorian mourning and New Brunswick mourning rituals. These practices seem to have infiltrated society early on, with hair wreaths and half-mourning costumes dating from the mid-nineteenth century in New Brunswick. Through the examples shown here and the prevalence of these items in other Canadian museums, we can ascertain that not only were these mourning rituals practised in late-nineteenth-century New Brunswick, but that they brought a certain level of comfort to those in need of it.

30 This Research Note charts an important historic aspect of New Brunswick culture. Museums in the southeastern region of New Brunswick have played in integral part in this research by preserving these primary sources. Having access to these artefacts in New Brunswick museums allows researchers to provide scholarly context on the visual and material history of the province. The preservation of these object of mourning illustrates that New Brunswick settlers were participating in cultural traditions brough from England and marking the province as part of the British Empire through these visual and material cues.41