Editorial

The Many Lives of Jackie Vautour

1 The death of Jackie Vautour in February 2021 did not come as much of a surprise. It was widely reported in the press that the 92-year-old was not well; and this was confirmed by photos of him during his last court appearances that continued up to the very end as he never stopped contesting the legitimacy of Kouchibouguac National Park.

2 I only met him once during the decade or so that I researched a project dealing with the history of the park, but it was hard to get very far away from the very long shadow that he cast over the whole, sad story, try as I might. Indeed, when I started the project, I had the idea that what had been missing in earlier accounts was appropriate attention to the 259 families that, unlike Jackie and Yvonne Vautour, actually left their lands when they were expropriated, following creation of the park in 1969.

3 Indeed, I would bristle when I would tell people that I was working on a project about Kouchibouguac National Park, and they would reply, “You mean the story of Jackie Vautour.” But, in the end, even in trying to understand the people who left quietly, albeit unhappily, there was always the spectre of Vautour. In the course of numerous interviews, I learned how these expropriates were treated badly by officials who tried to get them to accept a pittance for their land, but I was also frequently told about the role that Vautour played in advocating for his neighbours to increase these payouts. In reading the expropriation files in the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, I found numerous typewritten letters that he wrote on the residents’ behalf, so numerous that I could recognize his typeface before looking at the signature.

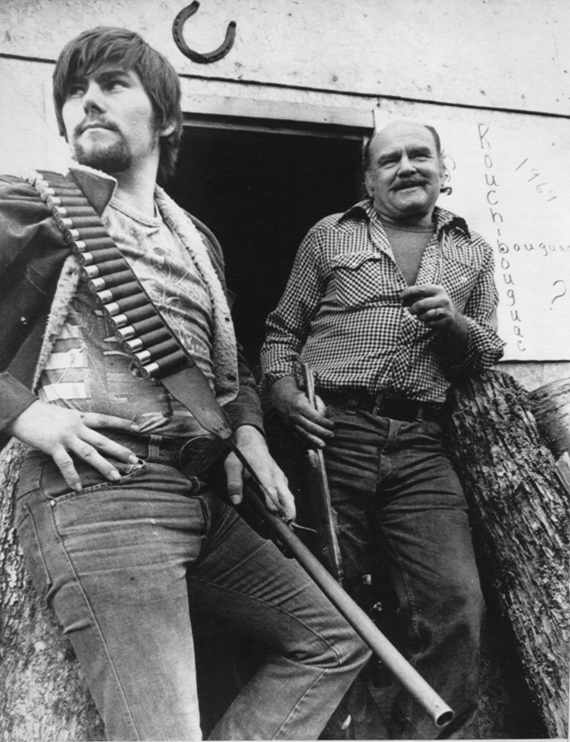

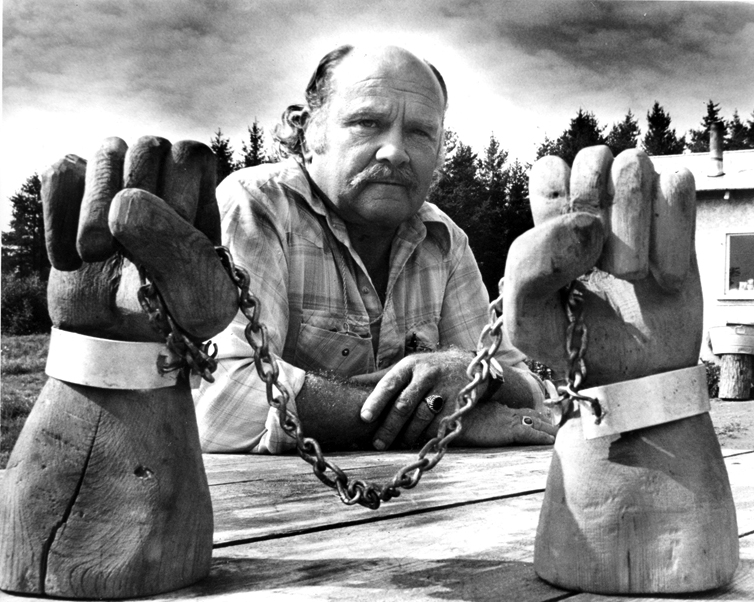

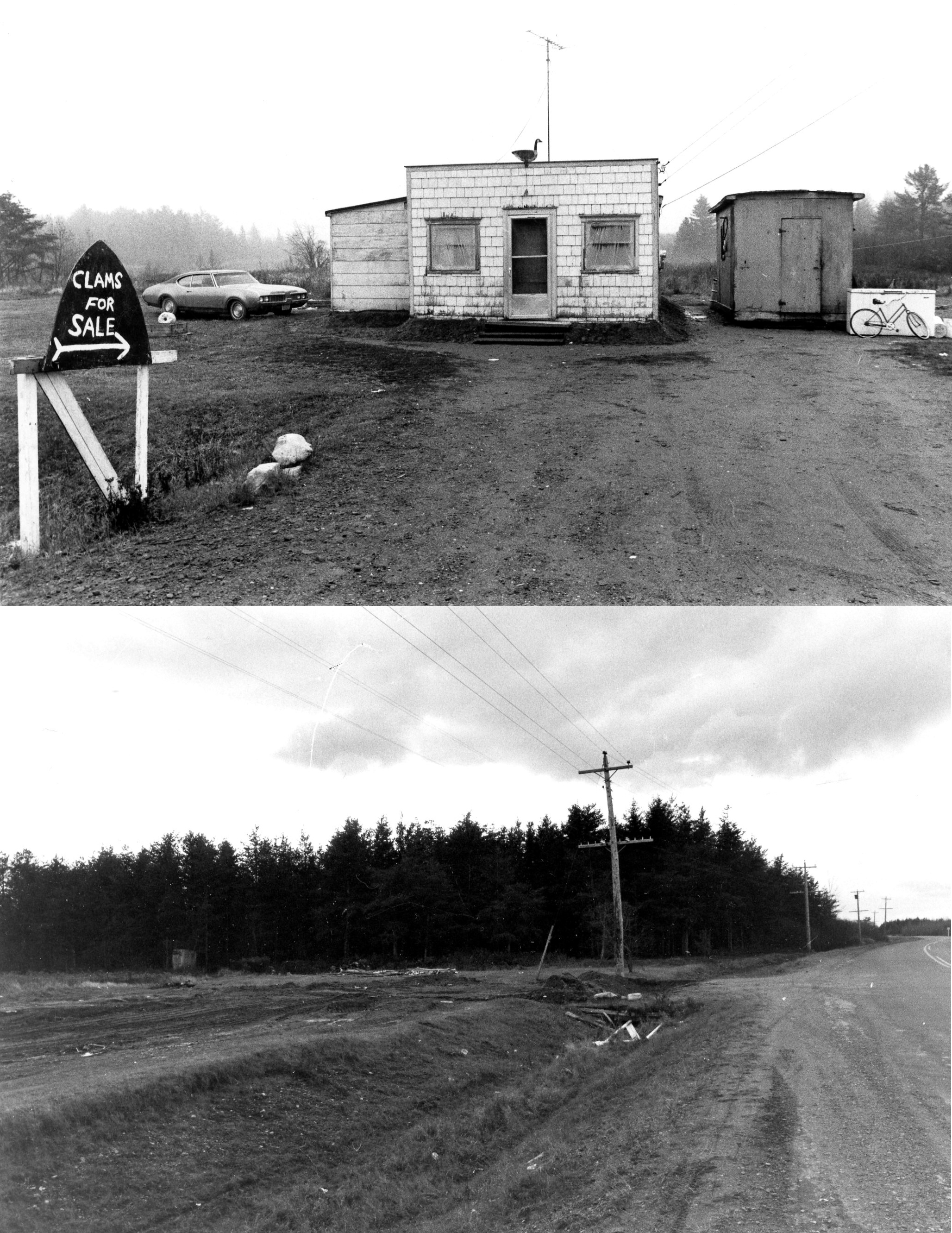

4 This version of Vautour -- someone attentively looking after paperwork, working within the system in support of others -- was not the one that I had expected to find, as his life ended up being defined by his own refusal to leave his land. Money could not resolve this situation because Vautour was convinced that the expropriation process was fundamentally illegitimate. In response to this resistance, in 1976 government officials carried out a carefully orchestrated operation to destroy the Vautours’ property, hiding the rubble left behind to make it appear as if the Vautours had never lived there. Almost overnight, the Kouchibouguac story was transformed from one about poor people -- both English-speakers and Acadians -- being mistreated by the state into one that was specifically Acadian as the Vautours became victims of what now came to be seen as “une deuxième déportation.”

Display large image of Figure 1

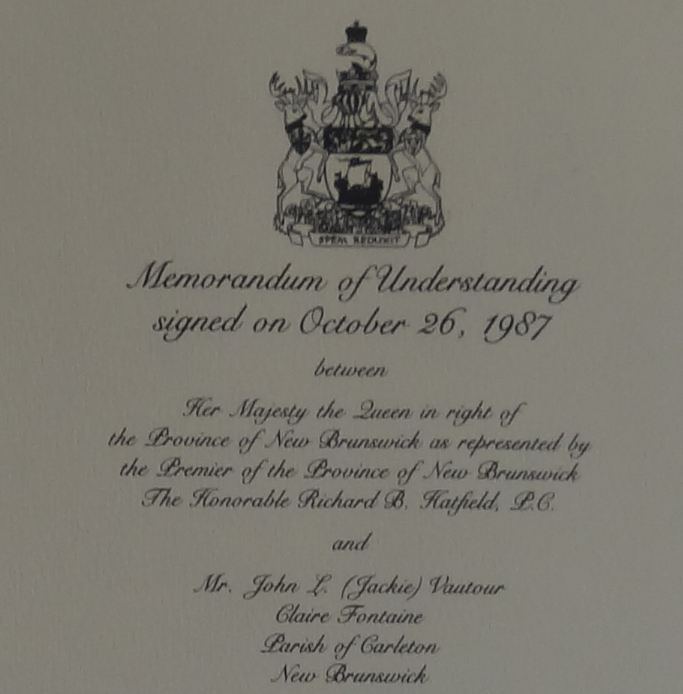

Display large image of Figure 1

5 Had the story ended there, then Vautour would have fit into a long-standing narrative -- best represented by Longfellow’s Evangeline -- that saw Acadians stoically accepting their fate. But Vautour pushed back, returning to his land in 1978, where he stayed until his death, in the process providing a model of resistance for those who wanted to more forcefully advance Acadian interests. This selfassuredness was evident in demands by Acadians for control over their schools, or in the creation of the short-lived Parti acadien that advocated for a separate province for the French-speakers of New Brunswick. But the single, most visible symbol of this Acadian assertiveness was the presence of the Vautours, thumbing their noses at authority.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

6 In the first years after the family’s return, government officials talked about forcibly removing them, but this course of action seemed only likely to stir up further unrest, after demonstrators closed down the park in March 1980. In order to lower the temperature, a Special Inquiry concluded that the Vautours should be allowed to stay on their land as long as they lived off the grid and without the right to deliveries or services. At the same time, the commissioners, Gérard La Forest and Muriel Kent Roy, recommended that additional payments should be made to the former residents, buying social peace. Interviewees never failed to tell me how they ended up with more than would have been the case if Vautour had not stirred the pot.

7 To be sure, in the forty years that followed, Vautour’s actions often alienated members of the community, creating divisions between those who supported him and those who were more guarded. For instance, in 1987, on his last night as Premier, Richard Hatfield invited the Vautours to his residence to sign an agreement by which they would leave their property in return for $270,000 along with two parcels of land where they could restart their lives. In the end, however, the Vautours weren’t going anywhere, claiming that the money went to pay for lawyers and that the title to the land was not clear. Many former residents were troubled that their own silent departure had earned them relatively little compared to this payout, although there was no sign that the money had improved the Vautours’ quality of life.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

8 More recently, divisions within the community were sown by Vautour’s decision to challenge the legitimacy of the park by claiming Métis ancestry. As he put it in 2007 at the premiere of a documentary film about his life, “If you are an Acadien or a Québécois, you are most likely Métis. I encourage you to join the real struggle for social justice. I encourage you to join the Métis.”1 In order to pursue this course of action in the courts, it was necessary to raise funds from the expropriate community; and while about one-hundred people supported Vautour, many others could not accept this claim of Indigeneity.

9 I learned over the years, however, that it was always a mistake to confuse reservations about Vautour’s tactics with a lack of sympathy for what he had tried to do for his neighbours. This was driven home to me by one of the former residents that I came to know while researching my project. She had never indicated any support for Vautour’s most recent efforts to challenge the park, and so I wasn’t sure how she would react to his death. What I learned was that she had frequently looked in on the Vautours as his health was declining, because this is what you do for your neighbours, particularly ones that had given their lives for the community.

10 Jackie Vautour was a complicated person, but there is no denying his legacy. Due to the resistance that he led, Parks Canada abandoned its longstanding policy of removing people against their will to create new national parks. This was a flawed policy from the start, based on the assumption that the residents had to leave so that “nature” could be displayed to tourists, something that would be impossible if people were in the way, as if nature only existed where there was no human presence.

11 But most conspicuously, Vautour left his mark on Acadian New Brunswick. In recognition of his role in redefining what it meant to be Acadian, he has been featured in the visual arts as well as in novels, poetry, theatre, and music. As for the larger Acadian public, while time may dim Vautour’s legacy, it was still alive and well at the turn of the millennium. When Acadie nouvelle asked readers to identify the most important Acadians of the twentieth century, Vautour figured in the top ten; and when the historian Marc Robichaud asked Acadian high school students in New Brunswick to compose brief essays about their province’s history, only two figures from the twentieth century were identified: Louis Robichaud (who as Premier in 1969 was responsible for the park) and Jackie Vautour.2

12 I will close by way of reference to my afternoon in the Vautours’ trailer in 2011. I had hoped to interview him, but he made it clear that nothing he said could be on the record, leaving me with only a series of impressions. I recall that on one wall there were a series of images which in a sense represented the arc of his life: A photo of Vautour nicely dressed in a suit and tie for a meeting in Ottawa with Jean Chrétien (the minister responsible for Parks Canada) in 1974 spoke to his efforts to secure better terms for his community; a newspaper sketch showed him on a cross marked November 1976, the month his house was destroyed; a tribute to him on the thirty-fourth anniversary of the bulldozing portrayed the residents as victims of a genocide, and those convicted for supporting them as political prisoners.

13 In addition, I recall how the Vautours hosted a steady stream of visitors, who were made to feel welcome. It was almost as if the Vautours were living a normal life, but in the end this was a badly deteriorating trailer when I was there a decade before his death. Efforts to repair the Vautours’ home were blocked by Parks Canada, which had barred the provision of services since 1980. Indeed, during my afternoon with the Vautours, I noticed that RCMP cruisers frequently slowed down in front of the trailer; I was told that they were making sure that no one was violating the rules.

14 Jackie Vautour’s life ended up being defined by his efforts to cling to his property, the perfect metaphor for a people whose history was to a large extent defined by their own dispossession. In that regard, it is hardly surprising that he became a mythical figure. But it is worth remembering that he was also someone who simply worked for and with his neighbours.