Refereed Articles

The New Brunswick NDP:

Trapped in Quicksand and Sinking

Abstract

This article examines the New Brunswick New Democratic Party’s increasing irrelevance post-2000. With successive one-term governments, the NDP has been unable to capitalize on voters’ desire for change, while watching the Green and People’s Alliance Parties emerge and grow to supersede them. Several factors at the heart of the NDP’s struggles are illuminated, including a turnstile leadership approach, organizational challenges, and campaign strategies, while spillover effects from the federal NDP party are limited. The New Brunswick NDP currently finds itself in a precarious position—merge with one of the other provincial parties or risk becoming politically extinct in New Brunswick.

Résumé

Le présent document examine le manque de pertinence grandissant du Nouveau Parti démocratique (NPD) du Nouveau-Brunswick après l’an 2000. À mesure que des gouvernements d’un seul mandat se sont succédés, ce parti n’a pas été en mesure de saisir le désir de changement des électeurs pendant que le Parti vert et l’Alliance des gens naissaient et prenaient leur envol pour le remplacer. Plusieurs facteurs au cœur des difficultés du NPD sont mis en lumière, notamment un leadership changeant, des défis organisationnels et des stratégies de campagne, alors que les effets du parti NPD fédéral sont limités. Ensemble, ces éléments ont fait en sorte que le NPD du Nouveau-Brunswick se trouve actuellement dans une position précaire — se fusionner avec l’un des autres partis provinciaux ou risquer de disparaître de l’arène politique du Nouveau-Brunswick, là est la question.

Introduction1

1 This article examines the New Brunswick (NB) New Democratic Party’s (NDP) increasing irrelevancy in the province. Political opportunities created by one-term governments post-2000 have not been seized upon by the NDP. Strong internal party divides have led to either strong leftist or centrist policies and platforms leaving potential supporters confused as to whether the party sits on the left or the centre of the political spectrum. A turnstile leadership approach—nine party leaders since 2000—has not helped matters. Nor has questionable campaign strategies surrounding party infrastructure and resource allocation, which has contributed to the NDP’s stagnation and marginalization. This has allowed other third parties such as the Green and the People’s Alliance to surpass and crowd out the NDP, thus questioning the party’s relevancy in an increasingly volatile province, and leading to a thorny question: Should the NDP merge with one of the other parties? This is the question explored below. We begin by first briefly exploring the NDP’s roots in the province and its recent electoral success. We then explore the challenges posed by a turnstile leadership approach post-2000 before turning to spillover effects from the federal NDP in the province. The article concludes with lessons learned and how the NDP can move forward.

New Brunswick, the NDP, and Electoral Success

2 The New Brunswick NDP’s roots lie in the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in the late 1930s and 1940s. Since its founding, the party has been plagued by a lack of funds (accepting donations only from citizens) and poor organization (Loree and Pullman 1979). Core support originated in Moncton and Saint John, two of the province’s more populous and industrialized cities at the time, and in Madawaska County, a largely rural area in the province’s northwest and site of a pulp mill in Edmundston. However, a less-than-receptive mainstream media frustrated efforts to get the party’s message out, and the party waned in its early years (Lewey 2012). The Robichaud Liberals (1960–1970) were also strategic in moving left with their progressive Equal Opportunity Program, thus stymieing the growth of the NDP. At the same time, the province’s labour movement was largely uninterested in its own party, preferring instead to work with the mainstream parties (Webber 2009).

3 By the late 1960s, the NB NDP underwent a metamorphosis with attempts to merge the Old Left and New Left. A New Left/Trotskyist group emerged within the party and became known as the New Brunswick Waffle. This internal struggle led to deep party divisions, federal NDP intervention, and eventual collapse of the Waffle by 1971. It did, however, lead to the anchoring of labour interests in the party, if only to prevent future attempts to take it over by other interests. At the same time, the events forced the party to acknowledge new concerns related to feminism, the environment, and societal institutionalization, all areas that would shape the party for the next forty years (Webber 2009).

4 However, poor party organization and funding continued to plague the party. As Carty and Eagles explain, the NB NDP was never able to establish “a competitive presence in most of the province’s electoral districts” (2003, 385). The fact that the NDP did not maintain local associations in every constituency was a significant problem. The emergence of the anti-Francophone Confederation of Regions Party in the 1980s, which formed the opposition for one term, revealed that the NDP’s real opponent was not the main governing parties, the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives, but other minor parties. Essentially, by the mid-1990s, the NB NDP had failed to identify its clientele, that is, the relationship between its support and the socioeconomic and linguistic dynamics of constituencies (Carty and Eagles 2003). Matters have not improved post-2000, as we will see below.

5 Loree and Pullman (1979) have explored these dynamics. As they argued, the factors needed to successfully build support for a third party such as the NDP—including an awareness of a common position, interests, and aspirations, and an identified common opposition among citizens—simply do not exist. As they explain, New Brunswick’s regions have their own subcultures largely built on traditional industries leading to multiple elite structures and interests. There is no unity among the working class, and an economy steeped in traditional industries (e.g., forestry, agriculture, fishing) has led to paternalistic working relationships. Combined with historically poor education and skills, people have been left with few options but to accept the status quo and work within it. A political system that has been historically rife with patronage has only further solidified the lack of change (see also Ullman 1990). Linguistic divides persist, with Francophones traditionally voting Liberal and Anglophones traditionally voting for the Progressive Conservatives, coupled with regional economies that tend to work against a common economic interest. A highly rural population at approximately 50 percent only reinforces regional economic interests.

6 There is merit to these arguments. However, the analysis is dated. To be sure, linguistic divides persist and amplify tensions and erode the development of common positions and interests. The ongoing struggle over bilingual rules for paramedics in the province and over French immersion is evidence of this deep and acrimonious divide (Poitras, 2019, 2020). However, recent changes challenge some of the factors identified by Loree and Pullman (1979) and others. For example, it can be argued that a common opposition does exist in the form of large multinational interests, such as the Irving empire, which control large segments of the economy. Yet challenging such powerful interests has often proved futile, as revealed by the experience of striking oil refinery workers in Saint John in 1995–1997, which led to the local union’s decertification, as well as unsuccessful attempts to start a rival newspaper in Woodstock, New Brunswick, in the late 2000s (McFarlane 2014; Livesey 2016). For Loree and Pullman (1979), workers are left with little choice and forced to accept their situation in order to survive, something that Acadians and Francophone Quebecers are quite used to (“survivance” in French; Vernex 1979; Cook, 2005).

7 Perhaps the greater challenges are systemic electoral issues. For example, Bowler and Lanoue (1992) argue that the share of the NDP vote depends both on voter characteristics and the competitive position of the party in individual ridings. Overall, voting NDP is much more likely if one is a member of a union and identifies as a party supporter, whereas younger voters and Francophones tend to vote less for the NDP. For strategic voters, union membership is significantly linked to where the NDP is competitive in ridings, while protest voters are least likely to support the NDP in ridings where their preferred candidate and party are viable. Again, the research is dated and acts as a general rule of thumb. Yet outliers do exist, such as the case with long-time federal NDP MP Yvon Godin (Acadie—Bathurst, 1997–2015). This suggests that linguistic effects are dependent on the strength of the local candidate, underscoring that much work is needed at the grassroots level to cultivate interest in the party. Moreover, no doubt the provincial NDP has been challenged to address and replace union support. For example, the rate of unionization in New Brunswick dropped from 39.8 percent in 1981 to 26.7 percent in 2016, leaving it the third least unionized province in the country (Statistics Canada 2013, 2016).

8 As a smaller party, the electoral system also works against the New Brunswick NDP. Duverger long ago noted that single-member plurality electoral systems tended to impose two-party dominance depending on assembly size (mechanical effects) and the popular vote (psychological effect; Taagepera 2001). Taagepera (2001) expanded on Duverger’s insights by gauging the magnitude of the effect over the long term. Results were mixed, with the United Kingdom experience confirming that third- and fourth-place parties were significantly punished in both the number of votes and seats, while the top two parties’ seats and votes were significantly amplified. In the New Zealand experience (pre-1995, after which a mixed-member proportional electoral system has been used), results varied, especially for the third- and fourth-place parties. Their vote totals were depressed significantly as predicted, but seat counts were amplified, though not enough to be considered “mainstream.” This is instructive and suggests that institutional effects are largely responsible for the results of minor parties. For the New Brunswick NDP, this is important, but while the electoral system may work against them, it does not rule them out or relegate them to insignificance in the process. The rise and success of the Green and People’s Alliance Parties in New Brunswick are evidence of this fact. This suggests that other factors such as leadership and party organization are at play (see also O’Byrne and Ericson 2011).

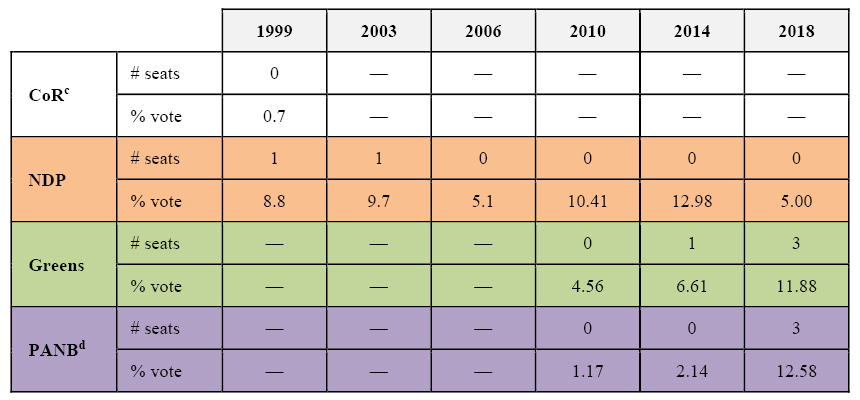

9 The above factors have led to little electoral success for the New Brunswick NDP. It managed to elect one MLA in the 1982 election (Robert Hall); a second MLA in a 1984 by-election (Peter Trites), who crossed the floor to sit as a Liberal prior to the 1987 election; and a third MLA (Elizabeth Weir) in the 1991 election, who was re-elected in 1995, 1999, and 2003. Post-2000, outside of Weir, no NDP MLAs have been elected. Since 1982, the party has consistently polled in the 10 percent range during elections, except in the 2006 and 2015 elections (5 percent) and in 2015, when it received its highest share of voter support at 13 percent (see Table 1). Post-2000, the NDP has been the largest minor party in the province, except in the 2018 election, when it was surpassed both in percentage of the vote and in the number of seats won by the Green Party and the People’s Alliance Party, as shown in Table 1.

10 Within the province, support for the NDP remains highest in the Saint John region, home to much of the province’s heavy industry, and in the Acadian peninsula (Bathurst), with its long history of mining. A distant second is in the province’s southeast region. However, traditional areas of NDP support have increasingly been taken over by the other minor parties as they have grown.

Display large image of Table 1a Excluding minor fringe parties such as the Natural Law Party, the Grey Party, Keep It Simple Solutions Party (KISS), and Independents. b Source: Elections New Brunswick, 2019. c Confederation of Regions Party. d People’s Alliance Party of New Brunswick.

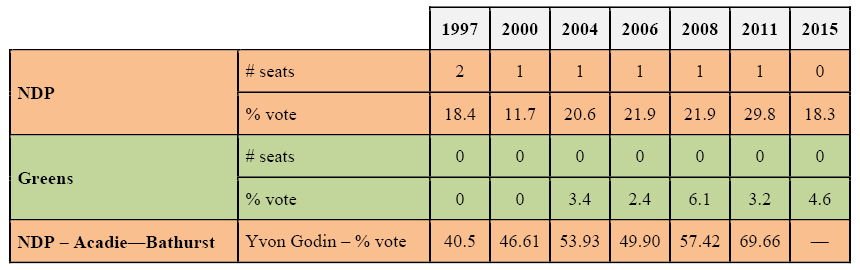

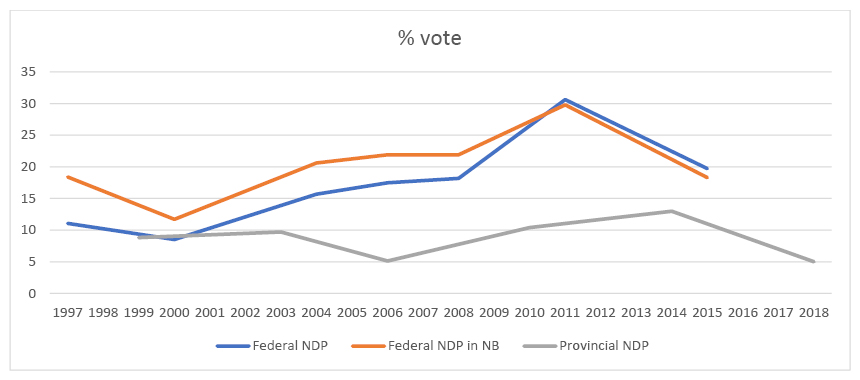

Display large image of Table 1a Excluding minor fringe parties such as the Natural Law Party, the Grey Party, Keep It Simple Solutions Party (KISS), and Independents. b Source: Elections New Brunswick, 2019. c Confederation of Regions Party. d People’s Alliance Party of New Brunswick. 11 Federally, NDP support in New Brunswick has ranged from a low of 11.7 percent in 2000 to a high of 29.8 percent in 2011 (Table 2). This is significant in a province that lacks a strong class consciousness (Peacock 2013). Party support also centres on one riding, Acadie—Bathurst, where Yvon Godin won six consecutive elections. The only other federal NDP candidate to be elected in the province was Angela Vautour in 1997, who was also hugely popular, yet defected to the Progressive Conservatives ahead of the 2000 federal election (Elections Canada 2019). It is important to note that the popularity of the NDP in New Brunswick consistently polled either ahead of or consistent with the NDP nationally (Figure 1). In comparison, the provincial NDP has consistently polled lower (Figure 1).

Display large image of Table 2a Excluding minor fringe parties such as the Canadian Action Party, Marijuana Party, and Natural Law Party. b Source: Elections New Brunswick, 2019.

Display large image of Table 2a Excluding minor fringe parties such as the Canadian Action Party, Marijuana Party, and Natural Law Party. b Source: Elections New Brunswick, 2019.  Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

12 Election results illustrate that there is uptake for the NDP in New Brunswick, but it may largely rely on strong candidates as the Godin and Vautour federal election wins demonstrate, as well as Elizabeth Weir’s provincial electoral wins. However, beyond the odd electoral win, NDP uptake is stunted at the provincial level and has recently been overtaken by other minor parties.

Turnstile Leadership

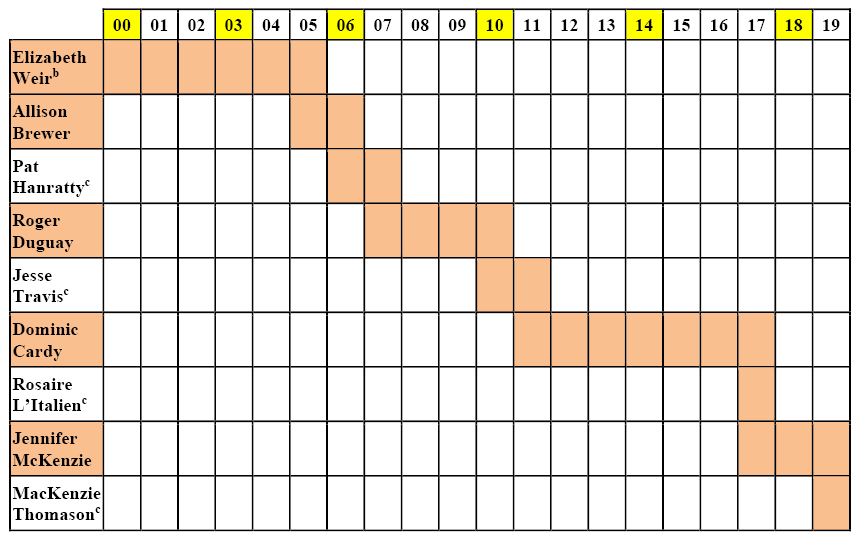

13 Leadership troubles have plagued the NB New Democratic Party since 2000. At issue is the longevity of party leaders who have typically been given one electoral opportunity to make gains (i.e., secure a seat for themselves and/or elect some MLAs) before being replaced (Table 3). A high turnover in party leaders is not unusual during times when parties struggle to define or redefine their identity, as witnessed in other provinces, such as Quebec with the Parti Québécois,2 and federally with the Liberal Party3 (Davies 2006). In New Brunswick’s case, the NDP has had, post-2000, nine party leaders (including four interim leaders), which underscores the challenges with party organization, including succession planning.

Display large image of Table 3a Yellow shading indicates election year. b Elizabeth Weir was leader of the NB NDP from 1988 until 2005. c Interim leader.

Display large image of Table 3a Yellow shading indicates election year. b Elizabeth Weir was leader of the NB NDP from 1988 until 2005. c Interim leader. 14 The NB NDP entered the new millennium with its long-time leader Elizabeth Weir. Weir was elected leader in 1988 and gained a seat in the legislature in 1991, holding that seat through three more elections until her resignation as party leader in 2005. No NDP leader or member has since been elected to the legislative assembly. Weir, a Belfast-born and Ontario-educated lawyer who taught at the University of New Brunswick, was an intimidating figure who quickly became the conscience of the legislature (Cunningham 2017; CBC News 2004). She rallied against public-private partnerships and legislated public-sector wage freezes, promoted legislation to prohibit the use of replacement workers in labour disputes, and addressed issues related to pay equity, women’s rights, environmental protection, poverty, and low-income earners (Frank 2013; Poitras 2005). Weir clearly situated herself and the party on the left of the political spectrum and resisted offers to switch parties, once stating her preference to “gnaw off [her] own right arm” rather than abandon her principles to join the McKenna Liberal government (CBC News 2004). Yet, as effective as Weir was in championing issues, she was never able to increase NDP representation in the assembly. The NDP was Weir and Weir was the NDP. To that end, Weir rarely campaigned outside of her own Saint John area riding or the capital region of Fredericton. The northern and Francophone parts of the province were largely seen as “arid soil” (Gravel 2017).

15 Two short-term leaders, Allison Brewer and Roger Duguay, followed Weir’s retirement. On the surface, Brewer (2005–6) seemed to be an excellent NDP leader. As a single gay woman with three children, one of whom has a disability, she was potentially able to draw upon many traditional NDP constituencies for support. Brewer also had an intriguing background in being a native New Brunswicker (born in Fredericton) and having been the long-time Director of the Morgentaler Clinic in Fredericton before moving to Iqaluit in 2000 to work for the Nunavut government. She returned to the province in 2004, and, encouraged by her long-time friend Elizabeth Weir, ran for and won the party’s leadership.

16 Yet the challenge Brewer faced may have been insurmountable. First, Brewer followed Weir, who was a strong leader (O’Byrne and Ericson 2011). As Desserud explains, in such cases, parties tend to struggle, as seen with the leaders who followed Frank McKenna, Pierre Trudeau, and Brian Mulroney (Davies 2006). Brewer herself admitted that she “could feel the comparisons” to Weir and that she could never capture the public’s imagination the way that Weir did (Davies 2006). Second, Brewer decided to run in her home riding of Fredericton—Lincoln against a seasoned political veteran and former cabinet minister, Greg Byrne, rather than run in Elizabeth Weir’s old riding in Saint John (CBC News 2006a). Third, media coverage of Brewer’s campaign significantly undermined her (and her party’s) chances of being elected, since it focused mainly on her sexual orientation and the fact that she was a woman and a strong advocate of reproductive choice (Everitt and Camp 2009). New Brunswick was not yet ready to accept such an individual, even with a strong leftist campaign focusing on a prescription drug plan, affordable child care, additional school funding, an update to the province’s labour laws, and an environmental cleanup of Saint John’s harbour (NB NDP 2006; MacLean 2007; CBC News 2006a). Fourth, evidence suggests that the party was not fully welcoming of Brewer. Roger Duguay, a former Catholic priest and Brewer’s successor, blamed her affiliation with the Morgentaler abortion clinic as a key reason for the party’s poor showing in the 2006 election (McHardie 2007). Fifth, the fact that Brewer had recently moved back to New Brunswick after being away for four years did not help matters, as voters had to reacquaint themselves with her. Given that Brewer was not bilingual also proved to be a significant challenge in a province that is one-third Francophone (McHardie 2007).4 Sixth, the fact that party leader is an unpaid position places significant financial stress on the leader, unless they are able to get elected, and was a significant reason why Brewer resigned after the NDP failed to elect a member in the 2006 election (CBC News 2006b; White 2007).

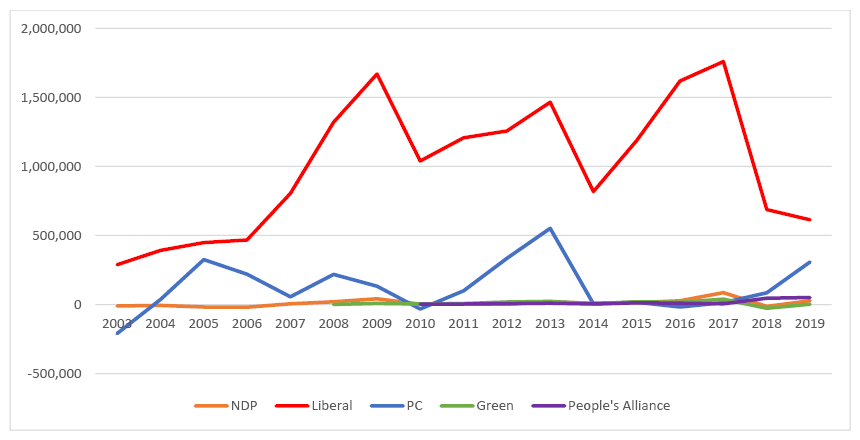

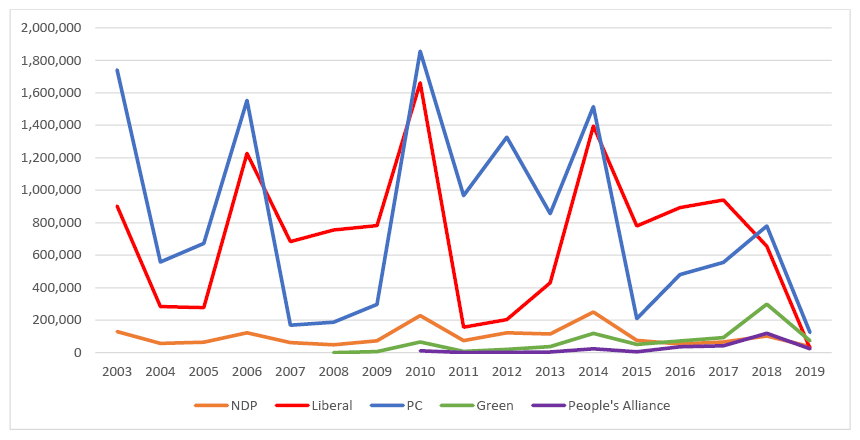

17 Roger Duguay, NDP leader from 2007 until 2010, fared no better. Duguay worked hard to build the party in the province ahead of the 2010 provincial election. Voters responded to his platform of fiscal responsibility and his attacks on corporate welfare, and the party doubled its share of the vote (NB NDP 2010). Duguay, like other leaders before him, spent the majority of the election campaign in his own riding, and yet he and other NDP candidates failed to get elected, despite the fact that that party had attempted to move to the centre of the political spectrum (O’Byrne and Ericson 2011; Telegraph-Journal 2011). This was no doubt forced on the party given its poor financial management, debt, and minimal fundraising (O’Byrne and Ericson 2011). A review of the financial statements by each political party submitted to Elections New Brunswick reveals that the NB NDP was in debt until 2006, after which it had modest accumulated surpluses, similar to the other minor parties but unlike the major parties, the Liberals and PCs (Figure 2). The NDP has also struggled with fundraising, lagging far behind the main parties while seeing their efforts eroded as the Green and People’s Alliance Parties have gained in popularity (Figure 3). The combined effect was to leave the NDP in a precarious position.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3Note: 2019 amount for the Liberal Party is for the first six months only.

Display large image of Figure 3Note: 2019 amount for the Liberal Party is for the first six months only. 18 Dominic Cardy (2011–17) built on Duguay’s work by moving the party to the centre/right, which proved to be controversial. Cardy, a UK native who moved to Fredericton as a youth, became involved with the NDP while attending Dalhousie University. He subsequently worked for the federal government for some time before working for the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs in Washington, DC from 2001 to 2008 (McHardie 2014). Upon his return to the province, he became involved with the NDP and, as leader, distanced himself from the party’s labour roots by removing seats set aside for organized labour on the party executive and supporting fiscal restraint (Poitras 2017). Environmentalists were alienated by Cardy’s support for shale gas development and the Energy East pipeline, while Francophones were angered by his criticism of the province’s dual busing system for Francophone and Anglophone students, and the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages for New Brunswick (Gravel 2017a; Poitras 2017; see also NB NDP 2014). Cardy’s successful recruitment of former high-profile Liberal and Progressive Conservatives to run as candidates for the NDP, as well as his acceptance of funds from large corporations, further alienated many party supporters (Poitras 2017). While many long-time party supporters appreciated the superior organization of the party and the elimination of its $300,000 deficit under his leadership, many left the party because they were not willing to accept the party’s centre/right shift, or they worked to have Cardy removed as leader (Telegraph-Journal 2013; Poitras 2017; Gravel 2017a). As divisive as Cardy’s leadership was, NDP support rose to 13 percent in the 2014 election, suggesting that voters were looking for an alternative to the two mainstream parties. However, no NDP MLAs were elected. Cardy himself failed to secure a seat in a subsequent by-election and, in 2017, resigned amid rising internal party conflict (Gravel 2017a; Cunningham 2017).

19 Jennifer McKenzie won the party leadership later in 2017 and quickly distanced herself from Cardy, announcing that she was taking “the party back to its core and...true to the type of party built by Tommy Douglas and other leaders like Ed Broadbent and Jack Layton” (CBC NB 2018; see also Gravel 2017b).5 McKenzie, a Fredericton native and engineer and long-time resident of Ottawa, was no stranger to politics, having been a two-time chair of the Ottawa District School Board and having run unsuccessfully in the 2014 Ontario election. She returned to New Brunswick and ran unsuccessfully as a candidate in the 2015 federal election in Fundy—Royal before winning the leadership of the provincial NDP. Her platform focused on more traditional NDP issues such as creating 24,000 child-care spaces, imposing pay equity on the private sector, and ending the privatization of health care (NB NDP 2018; CBC NB 2018). McKenzie also learned French comfortably enough to discuss issues in a citizen’s language of choice and regularly conducted media interviews in either language (Gravel 2017b).

20 Unlike past leaders such as Weir, Brewer, and Cardy, McKenzie engaged Francophone New Brunswickers, but she largely focused on her Saint John riding for most of the 2018 campaign, much to the chagrin of some candidates (Jones 2018). The party again was unable to secure seats in the 2018 provincial election and dropped to 5 percent support, which was difficult for party stalwarts to accept, since both the Green Party and the People’s Alliance Party had each elected three members. A subsequent leadership review vote revealed internal divisions, with a small majority of party members complaining that the party had not moved far enough to the left to recapture its roots. McKenzie promptly resigned as leader, stating that she did not share that vision (Ibrahim 2019). Former leader Dominic Cardy, who switched parties and was elected as a Progressive Conservative in the 2018 election, may have said it best when McKenzie won the NDP leadership, stating that while he wished her well, “It’s a hard job being leader of the provincial NDP. To run the NDP as a really democratic party and listening to all points of view, you’ve got to listen to people in a political party who don’t want to win elections and who want to adopt policies that are bad for the province” (Telegraph-Journal 2017).

21 The NDP’s turnstile leadership approach and associated issues post-2000 paint a bleak picture for the party, especially given the rise of other minor parties. Looking beyond the province, we turn to examine how the experiences at the federal level may help to improve the NB situation.

Federal Dynamics

22 While the federal and provincial wings of the NDP may be fairly well integrated (Chilibeck 2012), on the ground, the relationship remains frosty. Federal electoral success, where the NDP in New Brunswick has attracted from 18.3 percent to 29.8 percent of the vote between the 1999 and 2015 federal elections, has never translated into NDP support provincially. This may be due to a host of factors, including the fact that the federal NDP had largely abandoned the Maritimes to the dominant parties in the region (Liberals and Progressive Conservatives) given the few seats in the region (Loree and Pullman 1979). Even so, support for the federal NDP was strong, but this was mainly due to the hugely popular Yvon Godin in the Acadie—Bathurst federal riding. Godin, a long-time union organizer and leader, defeated Jean Chrétien’s senior cabinet minister Doug Young over what was essentially a referendum in the riding on the Chrétien government’s changes to Unemployment Insurance (now Employment Insurance) (Hill 2002). The key changes were to the qualification for benefits which were now calculated based on the number of hours worked (and not weeks), which reduced benefits for repeat claimants significantly and affected seasonal workers in the fishing and tourist industries that dominated the Acadie—Bathurst riding. Essentially, Young paid the price for the Chrétien changes (along with fellow cabinet minister David Dingwall) (Lamoureux 2012). With 40.5 percent of the popular vote, Godin easily defeated Young in 1997. Godin remained popular in five subsequent elections, attracting 69.66 percent of the popular vote in 2011, his last election (Table 2).

23 Despite Godin’s popularity, friction with provincial interests was significant. For example, Godin continually refused overtures to be the provincial party’s leader, but only after toying with the idea for some time (e.g., Telegraph-Journal 2006). Moreover, he remained engaged through the party’s labour wing and was opposed to moving the party to the centre under Cardy’s tenure, openly stating after the 2014 provincial election that “the problem, I think, with the provincial party, with Dominic, was that I think he was too much to the right to even be in the centre, and I think people read into that” (Gessell 2015). This ideological divide between the NB NDP’s labour interests and social democrats in moving the party to the centre undermined electoral progress for the party provincially.

24 A similar situation can be seen in Angela Vautour’s defection. Vautour was elected as an NDP MP in the 1997 federal election but crossed the floor in 1999 to join Joe Clark and the Progressive Conservatives, citing the fact that the federal NDP “was not moving to the centre quickly enough” (CBC News 1998). This was a significant blow to the Alexa McDonough NDP, since Vautour had won in a Liberal stronghold, Beauséjour—Petitcodiac, and had defeated the Governor General’s son, Dominic LeBlanc (Fraser 1999). Vautour lost in the next federal election to LeBlanc, but the episode illustrates the ideological tension that exists in the NDP and which has dominated the provincial party since 2000, thus contributing to its poor performance. Any positive federal spillover effect is minimal at best.

Moving Forward

25 Several lessons can be gleaned from an examination of the NB NDP post-2000. First, the turnstile leadership approach has worked against the party’s interests. For example, all of the leaders who have succeeded Weir spent considerable time outside the province only to come back to try to lead the party, hoping for a breakthrough. This is time-consuming in that the electorate must continually reacquaint themselves with the new leaders and what policies they support. A related issue is that leaders have had little time to achieve results since they were given only one election before they were forced out of the leadership. This “one-and-out” approach offers little time to build the party before a new leader arrives and the rebuilding begins anew, leaving voters confused and in search of another alternative. The turnstile leadership witnessed in the party is also a product of the party struggling to ideologically define itself. To form a government, the party will have to move and stay in the centre of the ideological spectrum where the majority of voters reside. This, however, works against the party’s historical orientation to not necessarily win elections, but to provide a moral voice in the public arena and keep the other parties honest (O’Byrne and Ericson 2011). This is similar to a point that Cardy made about the party when congratulating McKenzie when she became party leader. Seen in this light, we may be asking too much of the NDP since it sees itself largely as an interest group content to protest government initiatives.

26 Second, the party’s ideological divide ensures that electoral progress is minimal. Continually moving between the left and centre/right simply adds to voter confusion. We see this with Weir and Brewer being on the left, Duguay on the centre/left, and Cardy moving the party centre/right, which only alienated many party supporters. McKenzie moved the party back to the centre/left, but this proved to be not enough for party stalwarts and led to her resignation. The question remains of how the NB NDP can attract support when it is unsure of what and who it represents. Traditionally, voters hug the centre, either a little to the left or right. If the NB NDP wishes to be “hard left” as party loyalists seem to desire, then Cardy may be correct in his assessment (see O’Byrne and Ericson 2011).

27 Third, the party suffers from a poor organizational structure. Evidence of this can be found in the lack of remuneration for party leaders, thus limiting the length of time one can perform the role before having to find paid employment. Being the leader of a political party is a full-time job, and the NB NDP needs to attract funding to support its leader without which the turnstile leadership pattern will likely continue. By 2006, half of the party constituencies had disappeared. Continually rebuilding the party from scratch is time-consuming and draining, especially given limited financial resources, as Figures 2 and 3 indicate.

28 This puts pressure on party finances, a fourth dynamic. We saw how the party was hampered during elections, working to finance the leader’s campaign but providing only minimal support to other candidates (see also O’Byrne and Ericson 2011). In one way this is understandable, as one wants to have their leader elected so that they will receive enhanced media coverage from being in the legislative assembly. In another way, it starves other party candidates who may have a more realistic chance of being elected. Evidence of this is found, for example, with McKenzie’s decision to increase support for a northern riding late in the 2018 campaign (Jones 2018). One can also point to the party’s long-term debt of $300,000, which Cardy worked to pay off before the 2014 election. Such debt hampers what a party can and cannot do. Substantial funding is required to sustain the party, which is hard to obtain and divisive, as seen when Cardy accepted donations from large corporate interests. Many party members saw this as abandoning the party’s roots. Party organization and finances are not helped when historically the federal NDP had largely abandoned the region as part of its electoral calculation (Loree and Pullman 1979).

29 Fifth, succeeding a long-time and strong leader such as Weir was going to be a challenge, but even more so given the media’s portrayal of Brewer. This highlights the monopolistic control of the media in the province, with the Irvings controlling all the English-language dailies and most of the Francophone newspapers. This is significant because, as Couture (2013) outlines, the pro-business, pro-Irving conglomerate positions of its newspapers’ reporting and editorials undermines a healthy democracy. The Standing Committee on Transport and Communications Report (the Bacon Report) in 2006 stated as much when it called for changes to the media landscape (Canada 2006). Evidence of this biased and anti-competitive behaviour can be found in relation to Brunswick News’s undermining of an upstart Woodstock area newspaper in 2008–2009, the biased reporting of the (now failed) merger of NB Power with Hydro Quebec in 2008 (for which the Irving conglomerate would benefit greatly due to drastically lower energy prices), and strong support for a second oil refinery and liquid natural gas facility near Saint John, both owned by the Irvings (Couture 2013). Even their former journalists and editors have admitted as much (see Couture, 2013, for an overview; Tunney 2008). Of note is the fact that contrasting points of view are rarely presented (Pedneault 2010; Steuter 2004; Walker 2010).

30 The NB NDP’s challenges also reveal the province’s traditional moral orientation, which continues to this day, as evidenced with the election of three MLAs in 2018 for the People’s Alliance Party.6 The NDP was seen to be in the dark ages, as Duguay’s comments about Brewer’s work history discussed earlier revealed. Under such circumstances, it is little wonder that the party performed so poorly under Brewer’s leadership. Similar issues to a lesser degree plagued McKenzie’s campaign (for example, compare the media interviews conducted by Steve Murphy of CTV News Atlantic with Jennifer McKenzie and Blaine Higgs during the 2018 election campaign; CTV Atlantic 2018a, 2018b).

Conclusion

31 Moving forward, the largest issue for the NB NDP is to find and define their identity. What are they? A party on the left, centre/left, or centre/right? An answer to this question may hinge on what the party wants to be: a protest party or a party that wants to govern (and thus the need to win elections, as Cardy’s comments alluded to). After all, votes are typically in the centre of the political spectrum. Defining their identity was crucial but even harder in 2019 when the NB NDP policy stance was largely eclipsed by other parties. The provincial Liberals under then-leader Brian Gallant moved to the left to claim traditional NDP human rights issues such as equality, diversity, and pay equity. On the environment, both the Liberals and the Green Party have developed progressive environmental platforms, thus undercutting a long-time NDP issue (NB Liberal Party 2018; NB Green Party 2018). All parties agree that health care needs to be improved, but no one seems to know how to do it. Education suffers a similar fate, and on economic issues, support for aggressive taxation of large corporations has led the party nowhere. In fact, when the NDP became more supportive of the business community under Cardy’s tenure, support for the party reached to its all-time high of 13 percent in 2014.

32 A wedge issue is required for the NDP to aggressively champion to set themselves apart from the other parties. That issue must have significant play among voters, but what is that issue? Immigration may be one such issue, but it is undermined by the fact that New Brunswick attracts and retains few immigrants per year (Leonard, McDonald, and Miah 2019), so it is largely a non-issue. The continuing strong traditional moral orientation of the province suggests it may also be some time before immigration is truly embraced.

33 The NB NDP may be at a crossroads, with its best option being a merger with the Green Party, as suggested by many (Raiche-Nogue 2019). Yvon Godin, long-time former federal NDP MP for Acadie—Bathurst, has recently suggested as much. Moreover, the provincial NDP’s president, Douglas Mullin, has stated that he would “love to sit down with the Greens” (Telegraph-Journal 2019). Yet it would be hard to fathom such a merger, given that the Green Party would have to accept significant involvement from labour interests. This is likely untenable for the Green Party, as they would probably—correctly—recognize labour as a significant source of friction with others in the party. It is more likely that we will witness a split within the NB NDP, with labour interests staying in the party in its current form or forming a new party, and social democrats leaving to join the Green Party. To an extent, we are seeing this develop as labour has never been able to deliver the vote for the NDP. The 2018 provincial election alone is proof, with NDP support plummeting to 5 percent while the Green Party’s support rose to 12 percent, and it elected three MLAs. In short, the Green Party needs the NDP less than the NDP needs the Green Party. A merger between the two seems unlikely at this time, leaving the NDP in a precarious position—trapped in quicksand and sinking.