Articles

Representations of New Brunswick's Institutional Bilingualism in an Online Petition:

A Logometric Discourse Analysis

Using the methodological framework developed by the French school of textual data analysis, this article examines the social representations of institutional bilingualism in New Brunswick as expressed in an online petition launched in 2013, “Stop the hiring discrimination against citizens who speak only English.” To that end, we conduct an analysis of the “lexical worlds” of a corpus constituted of 2,372 individual comments made in English. Through the analysis, we show that the “lexical worlds” in the petition reveal indicators of social representations concerning, among other things, the majority/minority power relations between social groups and the notion of qualification in the context of work, as well as out-migration of New Brunswickers.

À l’aide du cadre méthodologique élaboré par l’école française d’analyse de données textuelles, le présent article examine les représentations sociales du bilinguisme institutionnel au Nouveau-Brunswick comme cela a été énoncé dans une pétition en ligne lancée en 2013 intitulée « Stop the hiring discrimination against citizens who speak only English ». À cette fin, nous effectuons une analyse des « mondes lexicaux » d’un corpus constitué de 2 372 commentaires individuels rédigés en anglais. Grâce à l’analyse, nous montrons que les « mondes lexicaux » de la pétition révèlent des indicateurs de représentations sociales concernant, entre autres, les rapports de force « majorité/minorité » entre des groupes sociaux et la notion de compétences dans le contexte du travail ainsi que l’exode des gens du Nouveau-Brunswick.

Introduction

1 In recent years, commentators on New Brunswick society and politics have frequently noted that public debates surrounding the province’s official bilingualism policies have grown in intensity and significance (Editor-in-Chief, 2012; Delattre, 2015; Poitras, 2016). Indeed, language policies were a recurring theme throughout the 2014–2018 mandate of Brian Gallant’s Liberal Party (Roy-Comeau, 2015; Roy-Comeau, 2019) and became an important issue during the following election campaign and beyond (Bundale, 2018). In this paper, we seek to deepen our understanding of antibilingualism discourse, and of the social representations of bilingualism contained within, through a textual analysis of a widely circulated online petition launched in 2013 titled Stop the hiring discrimination against citizens who speak only English (Wright, 2013).

2 According to Roulet, Grobet, and Filliettaz in Un modèle et un instrument de l’organisation du discours (2001), discourse “in all its forms, is central to all human activities, from everyday communication to media information, education, political debate or research” (p. 3). In this view, according to Denise Jodelet, speech conveys representations, which is to say images of various socially constructed objects, which are “circulated through discourse, carried by words, transmitted in media messages and images, crystalized in conduct and material or spatial arrangements” (Jodelet, 1997, p. 48). All interactions between individuals or groups activate collectively developed social representations, through which, according to Deaux and Philogène (2001) in Representations of the Social, “we make sense of the world and communicate that sense to each other” (p. 4). Jodelet (1997) notes that a group’s social representations “construct a consensual vision of reality for that group” (p. 52).

3 Representations are therefore social constructs reproduced through culture and socialization within a given group, and are an important factor influencing the group’s relationship with and attitudes toward other groups or socially constructed objects. Jodelet (1997) notes that one group’s consensual vision can “come into conflict with another group’s” consensual vision, notably because of

4 The context of this study—representations of official bilingualism in responses to an online petition in New Brunswick—is characterized by stark differences in the representations of the relevant issues held by both groups concerned, as well as within these groups to some extent (see Arrighi and Urbain, 2013; Boudreau and Dubois, 2003; Johnson, 1985; LeBlanc, 2009; Steele, 1990; Hayday, 2002, 2015). Although the debate pertains mostly to institutional bilingualism in the province of New Brunswick, which is to say to the bilingual capacity of provincial public services, individual bilingualism (more specifically the disparity of the bilingualism rates within each of the English and French official language communities) is also central to the discourse. In light of the significant gap in bilingualism rates between French mother tongue and English mother tongue New Brunswickers (approximately 70% of Francophones consider themselves bilingual compared to approximately 17% of Anglophones) (OCOLNB, 2018), there is a common perception—which our analysis will highlight— that both linguistic groups are not affected in the same way by bilingualism requirements for jobs. Consequently, this uneven capital, in the context of an economy which increasingly values it (see Heller, 2008), leads to an impression among some Anglophones, and presumably among a smaller number of Francophones, that bilingualism requirements for jobs (particularly in the public sector) constitute a form of discrimination against the largely unilingual English-speaking majority community.

5 Throughout New Brunswick’s (and Canada’s) history, issues related to institutional bilingualism have taken different forms and have impacted multiple areas of public life. Despite the provincial government’s official discourse’s emphasis on the good will that exists between both linguistic communities in the province (see Arrighi and Urbain, 2013; Boudreau and Dubois, 2003; LeBlanc, 2009), Canada’s only officially bilingual province has been and continues to be a hotbed of sociopolitical friction and conflict.1 These public debates, as well as the concerns over institutional bilingualism they bring to light, take place in a wider sociopolitical context that has been the topic of more than a few studies in the field of social sciences over the last 30 years (to name a few: Johnson, 1985; Steele, 1990; Hayday, 2002, 2008, 2015; Charbonneau, 2015).

6 The corpus we propose to analyze as part of this study has been extracted from an online petition hosted on www.change.org, Stop the hiring discrimination against citizens who speak only English (Wright, 2013), which attracted more than 7,750 supportive responses throughout 2013.2 While some studies have previously been conducted on discourse against institutional bilingualism—typically by way of content analysis or of qualitative analysis of smaller corpora—to the best of our knowledge none of them (with the exception of Bouchard, 2019) has approached the subject through a textual data analysis or with an online petition corpus. These contrasting approaches, as well as the contextual particularities of each corpus (namely, the varying language policies or controversies involved), render an explicit comparison of the results of our analysis with previous studies difficult. We will however make some general observations in the final section of this paper, with no claims to exhaustiveness, pertaining to commonalities identified with earlier research on the topic of antibilingualism discourses.

7 The originality of our study resides in the advocatory nature of our corpus, which has an impact on the points of view that are included and will allow us to adopt a descriptive (as opposed to contrastive) approach to the study of this discourse in its current form. Our aim will be to identify social representations of institutional bilingualism in New Brunswick through an analysis of the “lexical worlds” which constitute the comments published as part of the online petition Stop the hiring discrimination.

Theoretical and methodological framework

8 According to Denise Jodelet, social representations can be defined as “a type of socially constructed and socially shared knowledge which has a practical purpose and contributes to the construction of a common reality for a social group” (1997, p. 53). Thus, as Serge Moscovici points out, the study of social representations requires that we adopt methods of observation as opposed to experimentation since these representations appear as a depiction of the object that is directly presented to us, or at least inferred, through various linguistic, behavioural, or material expressions (p. 61). Therefore, discourse is one of the channels through which representations, both individual and social, are expressed and circulated.

9 Although they are a type of knowledge, representations differ from scientific knowledge in that they are the result of what Jean-Blaise Grize calls natural logic (1997, pp. 171–172) and amount to a “common sense knowledge” (Jodelet, 1997, p. 53). By “natural logic” we mean a logic that is discursive—materialized in discourse in the form of a schematization—that “takes into account the content and not merely the form of thought” (Grize, 1997, pp. 171–172). According to Grize (1993), all communication is in fact a situation of interlocution, in which the speaker creates a discursive schema based on their cultural referent, on the representations they hold of the relevant object, and of their aims; this schema contains images of the speaker, the interlocutor, and the object, and is then reconstructed by the interlocutor in light of his or her own representations, cultural referents, and aims (Grize, 1993, p. 7). Schematization is thus partial (that is, incomplete) and listener-oriented: “it is partial insofar as its creator only includes within it that which he or she judges to be useful towards his or her aims, conductive to the intended effect; it is oriented insofar as it is organized by the speaker in such a way as to ensure the listener understands the message as it was intended” (Grize, 1997, p. 175). From this perspective, according to Patrick Charaudeau (1992), in order to access the representations that underlie the text beyond linguistic, semantic, and discursive data, one also has to take into account its context and the “mechanisms behind the production of the communicative act which correspond to certain aims (to describe, to recount, to argue)” (p. 635).

10 In terms of their aims, according to Charaudeau, discourses—and especially those that are argumentative in nature—have a double quest, plausibility and influence, the success of which depends on the “shared sociocultural representations among group members’ experience and knowledge” (1992, p. 784). More precisely, in arguments, “discourse creates micro-universes intended for those it aims to influence, universes in which the different elements are organized in such a way as to naturally lead to the desired conclusions, to appear as self-evident” (Grize, 1974, p. 190). It follows that, in light of the above-mentioned dual purpose of argumentative discourses, the objects’ representations upon which speakers build their schemas are selected because the speaker expects them to resonate in the mind of the interlocutor(s). Accordingly, an analysis of these images, adequately situated within the context of the interaction, can allow us to identify social representations that, whether or not they reflect what the speaker truly believes about a given object, would at the very least constitute traces of the social representations circulating within the speaker’s social group. This hypothesis seems even stronger in the case of a collective corpus (in which there are multiple authors) because the latter allows an analyst to confirm the recurrence of these representations in some or all of the speakers.

11 By taking into consideration the frequency of the words constituting a corpus and their lexical environment (which is to say their co-occurrence), it is possible to not only identify the words more likely to evoke social representations, but also to define words on the basis of their textual environment. According to Pascal Marchand (1998), the hypothesis upon which rests the indexation of the words in a corpus is that an “author tends to use words that pertain to what he or she is talking about more frequently than words that are not relevant,…therefore the more frequent a word is in a document, the more it constitutes a representative indicator” (p. 49). However, when words are used in discourse contextually, the consideration of the other words used alongside them allows us to pinpoint the meaning they carry in the text. Thus, for Damon Mayaffre, contextualization appears as a prerequisite for semantic interpretation: meaning emerges from text and context (2014, p. 2).

12 Logometry, a method of analysis which combines textual statistics and discourse analysis and which is performed on data of the nature described above (presence/absence, frequency, and cooccurrence), is defined by Mayaffre as “set of document-processing and text statistics operations…which goes beyond graphic forms without excluding nor overlooking them, which analyzes lemmas or grammatical structures without making abstraction of the original material to which we must consistently refer ourselves” (2010, p. 22). This computer-assisted method of descriptive analysis, although it has an important quantitative component, also incorporates qualitative analysis (categories of discourse, syntagmatic relations, text and context of the words, etc.) (Charaudeau and Maingueneau, 2002, p. 78).

13 The chief statistical analysis method through which we will make sense of our corpus is the descendant hierarchical cluster analysis developed by Max Reinert (1993). It consists of an analysis of the “lexical worlds” of a corpus. According to Ratinaud and Marchand (2015), a “lexical world” can be defined as “a set of cotextual forms linked by their context and by the object to which they refer” (2015, par. 2). It follows that, as Reinert (1993) explains, “lexical worlds refer to referential spaces associated with a vast number of statements,” and in the case of a communal corpus, they point to the “common spaces” of a group at a given point in time. In this way, “lexical worlds” are related to the notion of “social representations” (p. 12). Thus, the analysis of “lexical worlds” that are shared by members of a group in the same communicative situation can provide clues about the social representations those members hold of a socially constructed object. Indeed, according to Reinert, in a collective corpus of this sort, “lexical worlds” are indicators of a group’s common referential space and are “a sign of a sort of cohesiveness connected to the speakers’ specific speech activity” (p. 13). Reinert’s method of descendant hierarchical cluster analysis offers a visual representation of these “lexical worlds” in the form of classification tables derived from the intersection of the units of context (segments) and the lexical units (words) of a corpus. This method permits the analysis of both the words and the text segments that are the most closely linked to each “lexical world” making up the corpus. The latter, segments identified as being among the most representative of their “lexical worlds,” will serve as examples to illustrate the way key words tend to organize themselves in relation to one another in our corpus to create meaning.

14 We will apply the method described above to our corpus, which will allow us to identify the representations held by the group of individuals who signed the petition Stop the hiring discrimination in 2013 with respect to New Brunswick’s institutional bilingualism. Our primary question is the following: what are the social representations of bilingualism communicated through these discourses?

Corpus

15 According to Robert Boure and Franck Bousquet in La construction polyphonique des pétitions en ligne (2011), the phenomenon of online petitions, which have been growing in popularity since the end of the last decade, has not received enough attention from researchers in the humanities and social sciences (p. 293). A particular feature of such a petition is that its supporters can, if they wish, post a comment alongside their signature explaining their reasons for signing while attempting to influence others into supporting the petition as well. These comments, signed by their authors, are publicly accessible on the petition’s web page. According to Contamin (2001), this aspect of the communication medium has an effect on the receiver of the message in the sense that the message is oriented not only toward the governing body to which it is officially addressed (the government of New Brunswick in our case) but also toward the general public.

16 In the context of Grize’s natural logic framework (1997), corpora extracted from online petitions have the inherent property of homogenizing the factors affecting the range of communicative situations contained within. First, the group of commenters finds itself in the same situation of interlocution (monologues, in written form, inherently argumentative); second, subjects are given the opportunity to share their thoughts on a given social reality or current issue (institutional bilingualism in New Brunswick, in our case). These messages are intended for a general audience, and the petition’s advocatory aims make it so that, theoretically at least, only individuals who agree with the point of view expressed in the petition’s title and description are included in the sample of discourse. Accordingly, the point of view common to subjects in our corpus is that French-English bilingualism requirements for some positions in the provincial public service amount to a form of discrimination against Anglophone New Brunswickers, most of whom are not bilingual.

17 In the year prior to the launch of the petition under discussion, New Brunswick’s official bilingualism policies had been the focus of some controversy. Notably, in November 2012, a group made up of 119 New Brunswick politicians, business leaders and other prominent citizens signed a letter criticizing Brunswick News—which owns the province’s three English-language dailies— for its papers’ coverage of bilingualism and duality issues, seen as “stoking the flames of discontent, thereby creating unnecessary division and increased tensions between communities” (CBC News, 2012a). In response, the Telegraph-Journal’s editor-in-chief attributed the uptick in language debates and tensions to three recent news events (Editor-in-Chief, 2012), namely: MLA Jim Parrott’s expulsion from David Alward’s Progressive Conservative caucus for his criticism of the alleged costs of “duality in healthcare” (CBC News, 2012b), prominent businessman Richard J. Currie’s comments on bilingualism and duality,3 and the meeting held behind closed doors by a legislative committee tasked with the revision of the Official Languages Act (CBC News, 2012c). While these controversies do not pertain directly to this petition’s grievances concerning employment in the provincial public sector, they have contributed to setting the stage for subsequent citizen movements and mobilizations, such as Stop the hiring discrimination, calling into question various aspects of official bilingualism.

18 The petition’s description, which appears on the www.change.org page under an image with the phrase “EQUAL RIGHTS FOR NB’S ENGLISH,” reads as follows:

19 In total, by the time the petition ended in late 2013, Stop the hiring discrimination had gathered 7,758 signatures, 2,372 of which were accompanied by comments ranging in length from one word (jobs) to 304 words, for an average of 37.66 words per comment. This corpus contains 4,425 different words representing a total of 89,338 occurrences. Once sorted and lemmatized,4 the corpus was subjected to lexical analysis using Iramuteq (Ratinaud, 2009), described in the following section.

Analysis

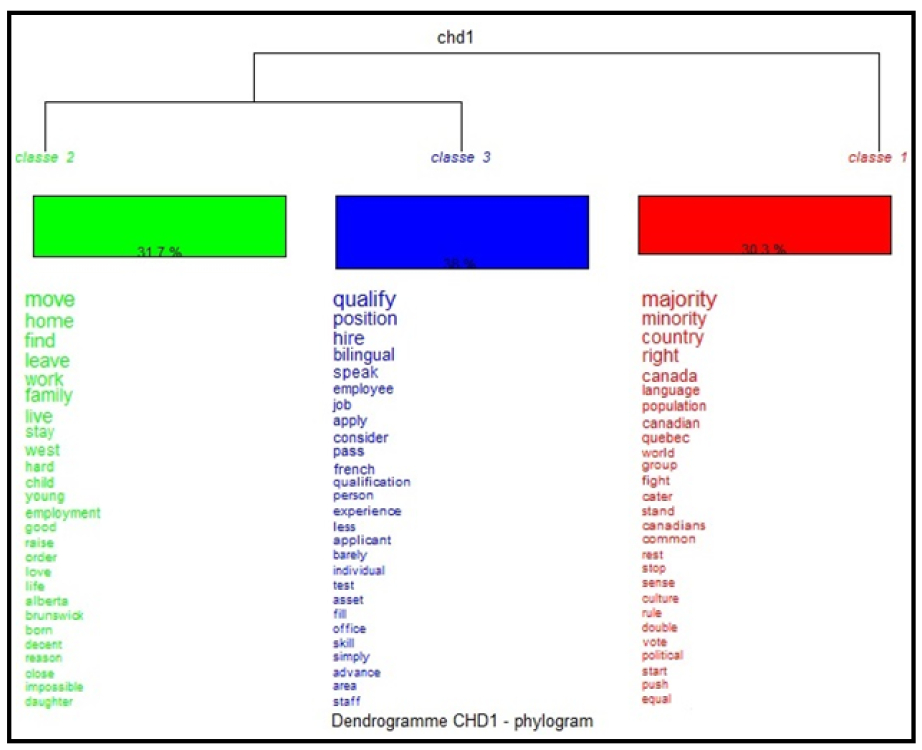

20 We used the Iramuteq open software (Ratinaud, 2009) to perform a descendant hierarchical cluster analysis (Reinert, 1993), examining the “lexical worlds” of our textual corpus. Our analysis divided the corpus into three distinct “lexical worlds,” as depicted in the three clusters in Figure 1:5

21 The first cluster (in red)6 which we will call the sociopolitical axis (30.3% of included segments) differentiates itself from the second cluster (in green) and from the third cluster (in blue) which are both more specifically related to the personal experiences of the respondents. The realm of personal experience is itself split into two distinct branches: Cluster 2 (31.7% of included segments) which we call the biographical axis, and Cluster 3 (38% of included segments) which we will call the professional axis. We will now examine the three “lexical worlds” which constitute this corpus.

The sociopolitical axis

22 Our analysis of the first cluster (Figure 1) reveals that the majority/minority dichotomy features at the forefront of this “lexical world’s” distinctive characteristics. This “lexical world” is also specifically linked to words that refer to geopolitical notions and concepts (country, Canada, population, Canadian, Quebec, Canadians), and to others that suggest the presence of political stances and/or claims (right, group, common, sense, rule, vote, political, equal). Words that refer generally to language and culture are also observed. Juxtaposed to these specificities of the first “lexical world” are verbs like fight, cater, stand, stop, start, and push which in this environment refer to social or political power relations.

23 More precisely, the power relations are presented through the lens of the social dynamics between linguistic minorities and majorities. Thus, in these discourses, a fair and just society in terms of linguistic and cultural policies is one that follows the principle of “majority rules,” as seen in the representative segments—identified by Iramuteq—reproduced below:7

24 Based on this reasoning, it would be unacceptable to require knowledge of the minority language from members of the majority group as a prerequisite for a job:

25 Considering New Brunswick’s current policy of institutional bilingualism, in which too many jobs are perceived to require bilingualism, power relations have been inverted at the expense of the Anglophone majority:

26 The status quo is perceived as being unfair and is seen as a form of discrimination against Anglophones on the basis of language, which results in a lack of opportunity and ultimately of representation within the labour market:

27 The sociopolitical grievances presented within the segments of the first cluster of our corpus are accompanied by verbs indicating the necessity that they be addressed:

28 This necessity, or even urgency, to act is attributed to the province’s economic situation, generally perceived as difficult:

29 Our analysis shows that, in the segments identified by Iramuteq as representative of the first cluster, the petition’s supporters tend to use the personal pronoun we, which gives their comment a sense of inclusion. On this subject, Charaudeau notes in Grammaire du sens et de l’expression that, in discourses that are political in nature, we can be used by the speaker to “describe positive actions and qualifications of the agents of social change” and thus serves as a call for solidarity (1992, p. 159):

30 We also see traces, in the first cluster, of representations concerning the relevance of bilingual services in an area where the linguistic minority is largely bilingual, the appropriateness of which should be re-evaluated in light of the province’s economic situation. Underlying the first cluster is the notion that the minority community’s advantage is due to its high rate of bilingualism; however, some commenters refer to the proportion of Francophones who do not speak English—9% of New Brunswick’s total population at the time (Statistics Canada, 2011)—as proof that services in French are not essential:

31 The exclusion of bilingual Francophones in assessing the value of French services highlights the representations on the role of public services, including translation, in the citizens’ mother tongue. Thus, the function attributed to these linguistic provisions is limited to a pragmatic one: French-language services lose their immediacy if one also speaks English. Put otherwise, Francophones implicitly lose their right to services in their language once they obtain knowledge of English. Furthermore, the notion that unilingual Francophones, like their Anglophone counterparts, would be disadvantaged by bilingualism requirements is conspicuous by its absence from the first cluster’s most representative segments. In fact, this “lexical world’s” predominant framing in terms of majority-minority power relations, in a certain sense, does not easily allow for the inclusion of unilingual Francophones to the discursive schemas.

32 Finally, references to the province of Quebec, and more precisely to its relationship with the other Canadian provinces, feature as a specificity of the first cluster of the corpus. The representations of Quebec expressed by the commenters are generally unflattering. Indeed, Quebec is perceived to be the driving force behind Canada’s institutional bilingualism while not being itself subjected to the same rules when it comes to accommodating its Anglophone minority:

33 In sum, in the first cluster, we find that the distinction between majority and minority is central to the representations in our corpus concerning the merits of language policies. The territorial delineation of Canada’s linguistic duality (French Quebec/English rest-of-Canada, instead of a pan-Canadian bilingualism) is thus an argument of convenience for detractors of official language minority rights. It implies a rejection, to varying degrees, of the officially equal statuses of French and English in New Brunswick that are put forth in official government discourses on language rights.

The biographical axis

34 The second “lexical world” of our corpus (Figure 1) is specifically focused on the perceived impact of the language policy on individual members of the largely unilingual majority group. This personal angle manifests itself in the second cluster through words like home, family, child, young, and daughter. For their part, the verbs provide context to this family experience: move, find, leave, work, live, stay, raise, love, and born. They speak to respondents’ anxieties about New Brunswick’s depressed economy, to its resultant demographic decline, and to the fear of having to leave their home province at a time when there are fewer and fewer well-paying and secure jobs outside of government. We find, for instance, some words in this “lexical world,” along with [New] Brunswick, which refer to a Canadian province, namely Alberta (West, Alberta). Finally, there are among the defining traits of our second cluster, a number of affective adjectives that qualify the life stories that are recounted: hard, good, decent, and impossible. The contents of our second cluster often evoke an exodus toward the Canadian West. While Cluster 1 was characterized by words pertaining to power relations within society, Cluster 2 is characterized to a greater extent by adjectives and other words conveying powerful emotions.

35 Considering this very personal language revolving around family and friends, it follows that the personal pronoun my is strongly associated with the second cluster:

36 Thus, generally, the second cluster comprises segments about the consequences of New Brunswick’s bilingualism requirements on the commenters’ personal lives. The most frequent consequence is out-of-province migration:

37 This exodus, in turn, contributes to the province’s dire economic situation because it affects young and working-age people, and constitutes what is often colloquially referred to as a “brain drain”:

38 When the commenters are not talking about New Brunswick, the Canadian province that is most closely associated with the segments of the second cluster is Alberta (also included in the word West). Alberta (and Western Canada more broadly) is thus the beneficiary of New Brunswick’s dwindling labour force:

39 Furthermore, the exodus described by commenters in the second cluster is generally presented as involuntary, one which is in some way imposed on them or their loved ones by necessity:

40 The second “lexical world” of our corpus also features a network of words, secondary by comparison with the theme of exodus, that relate to language learning. Most of the references to learning the French language in this cluster describe it as difficult, useless, costly, or inaccessible:

41 While some segments assert the limits of French immersion programs8 as they relate to achievement levels, others present the program as one of the few opportunities (if not the only one) for Anglophones to become bilingual:

42 From all this emerges a recurring discursive motif in the second cluster: in order to find a good job, or any job at all, one has to be bilingual, or else be forced to move to Western Canada. Throughout the segments that are most characteristic of the second “lexical world,” the commenters readily attribute hardships in the job market to the bilingualism factor.

The professional axis

43 The third and final cluster of our corpus (38% of segments), represented by the colour blue in Figure 1, is characterized by value-free descriptive verbs (qualify, hire, speak, apply, pass, advance), and by some adjectives and adverbs (bilingual, barely, less, simply) of which some are comparative by nature although nonaxiological. Among the words that define this cluster the most are featured semantic fields pertaining to work (qualification, experience, French, skill, asset, test) as well as to third parties (person, individual, employee, staff, applicant). Hence, the third cluster revolves around the theme of employment, more specifically around finding a job and advancing professionally. This cluster also features some of the only direct references in our corpus to language (other than the word language itself in Cluster 1): bilingual, speak, and French.

44 The topic of language is addressed through the lens of qualifications, and it is noticeable from the outset that the speakers tend to exclude bilingualism from what are considered legitimate job requirements:

45 In our corpus, this representation of bilingualism’s value with respect to work appears in the discursive schemas in the form of a trope. Here, an anecdotal (or hypothetical) “scenario” contrasts two candidates for a position, one highly qualified in terms of general skills and experience, and the other for whom bilingualism is the sole advantage:

46 Contrasts are clearly a defining feature of the third cluster. On the one hand, contrasts are established between candidates for a position, and, on the other, a distinction is made between the skill levels required for Francophones and Anglophones to be competent in their second language. The competency level expected of Anglophones is described as very—or too—high:

47 Conversely, the skill level required for a Francophone to be considered bilingual is described as inferior or inadequate:

48 While the segments constituting our third cluster frequently recount personal stories, they also often present third parties within the discursive schemas, whether employee, person, individual, etc. The function of these third parties within Cluster 3 is to demonstrate, with an appearance of being objective or a mere onlooker, the way in which the discrimination against Anglophones operates on the basis of bilingualism, a requirement that is seen as a lesser qualification for the purpose of employment. According to the participants in our corpus, bilingualism is thus an artificial requirement to a certain extent (unlike seniority, notably), and one whose assessment is subject to a double standard as it pertains to both language groups.

Conclusion

49 In order to answer our research question, we conclude that commenters in our corpus, supporters of the petition Stop the hiring discrimination, have selected “the aspects that have the most pertinent characteristics” (Vergès, 1997, p. 411) for the purposes of the petition with respect to the institutional bilingualism of New Brunswick. To recap, these characteristics involve power relations between majority and minority groups within a society (between Francophones and Anglophones on a provincial level or between Quebec and the rest of Canada at the federal level), the financial toll of bilingualism for a province in poor shape economically, the exodus of New Brunswickers (implicitly, Anglophones) toward Western Canada, the actual use of bilingual services in light of the high level of bilingualism within the Francophone community, the barriers to learning French, and the perceived imbalance in the assessment of bilingualism for Anglophones and Francophones. By virtue of their presence in our corpus, these images are endowed with negative connotations: they constitute different aspects of the process of discrimination to which the petition objects. The notion of causality (Hewstone, 1997, p. 281) can be observed through these representations of bilingualism, which seek to explain the causes of the injustice condemned by the petition.

50 While there is undoubtedly a certain amount of diversity of opinions expressed by the commenters in our corpus, our analysis shows a clear overlap in the representations that are presented in the discursive schemas, an effect in part of the advocatory nature of petition corpora as a whole. Indeed, despite the fact that each individual subject could not conceivably have addressed every major theme within their comment, the consensual vision of respondents that it presents is generally coherent: ultimately, institutional bilingualism is unfair because it benefits the minority at the expense of the majority, and that, despite the fact that the merits of individual bilingualism (for Anglophones at least) have yet to be demonstrated.

51 This general attitude toward official bilingualism in New Brunswick is in line with what previous studies have found throughout the years, and there are apparent similarities in terms of the selection and connotation of images of institutional bilingualism in our corpus. For example, already in her analysis of the briefs submitted as part of the public hearings on the 1985 Poirier-Bastarache Report, Catherine Steele (1990) had identified, among Anglophones opposed to further official bilingualism policies, a representation of language as it pertains to qualification that our analysis has revealed to be central to the professional axisof our corpus:

52 We have observed throughout our analysis and more explicitly in the sociopolitical axis of our corpus, in accordance with Arrighi and Urbain’s remarks in Le bilinguisme officiel au Nouveau-Brunswick (2013), a discourse characterized by an inversion of what are commonly seen as the usual power relations between majority and minority groups (p. 33). We have also noted the presence of criticism of “Quebec’s unilingualism”—despite the fact that it would not seem especially relevant to this petition at first glance—echoing a recurrent theme identified notably by François Charbonneau in Un dialogue de sourds? (2015, p. 30).

53 Thus, we can see how social representations within a group can be relatively stable. It is understood, however, that these representations of bilingualism (and perhaps more importantly of the merits of bilingualism as a required qualification within the public service) are by all available measures not representative of New Brunswickers’ views generally, and would not be entirely shared by New Brunswickers who favour such a policy, such as other Anglophones and members of the Francophone minority. This has been shown in previous studies on the representations Francophones hold of institutional bilingualism (such as LeBlanc, 2009, and Steele, 1990), as well as notably in studies on Anglophone parents’ advocacy for second-language instruction (Hayday, 2002, 2015), and reported in various opinion polls of both Anglophones and Francophones (see for example OCOLNB, 2013, and OCOL, 2016). While opinion polls typically affirm that the vast majority of New Brunswickers support the province’s language policies as a whole, much could be gained from a finer, language-centric probe of public opinion in order to add valuable nuance that is not grasped by simple questions such as “Would you say that you support the aims of the Official Languages Act?” (OCOL, 2016). It is our opinion that a computer-assisted discourse analysis of the sort we have used in this study would be put to great use by being applied to a pro-official bilingualism corpus, whether in the form of a comparable petition or of another form on online advocacy/argumentative communication.

54 While our analysis has suggested some commonalities with other studies of antibilingualism discourses, it has also put one of its current manifestations under a new light through methods of analysis developed within the French school of textual analysis. Notably, we have seen the central aspect of the majority/minority dichotomy within discourses pertaining to institutional bilingualism’s ideological or political merits. In the eyes of the supporters of this petition, opting out of the “majority rule” principle to cater to the French minority—at least in terms of providing public services, even if these are meant to equalize access—appears illegitimate. Just as offensive to them is the perception that, in the job market, there is a discrepancy in the evaluation of the levels of bilingualism of Francophones and Anglophones. The consequences of this double injustice in turn have a negative impact on the actors in our corpus, who attribute their family’s or loved ones’ exodus to the bilingualism requirement seen as too pervasive within the job market.

55 Moreover, the data and our analyses suggest that economic tensions have the potential to contribute to cultural-linguistic tensions. In the case of New Brunswick at least, it would appear that economic pressures are exacerbating negative attitudes surrounding bilingualism and contributing to a perceived competition between the two cultural-linguistic groups over dwindling resources. When the rights of the minority are considered an infringement not only on the rights of the majority, but also on the material well-being and the demographic vitality of the majority, the potential for positive cross-cultural relations becomes tenuous at best. The possibility that alleviating economic difficulties can serve to alleviate linguistic tensions, as well as the historical relationship between economic recessions and antibilingualism sentiments, therefore merits further study.

56 Further to the social and economic aspects of these discourses, the comments written by this particular group of (presumably all) Anglophones highlight the problematic confluence of their identity as members of both the linguistic majority and minority on a psychosocial plane: while Anglophones account for two-thirds of New Brunswickers, they only represent one-third of the province’s bilingual workforce (OCOLNB, 2018). This dichotomy leads to a sort of fracture in self-identity, which is to say that it seems difficult for the speakers to integrate these two identities and to reconcile the self-perception of being part of a majority (in terms of provincial demographics) with being part of a minority (when it comes to the proportion of New Brunswickers who have access to jobs requiring bilingualism).

57 Finally, we conclude by affirming that this thorny issue that has plagued New Brunswick for decades cannot be addressed without a clear understanding, facilitated by objective scientific studies, of the social representations both Anglophones and Francophones hold with respect to their own perceptions of bilingualism and their understanding of justice, fairness, equality, and democratic values. Without such a framework, no reflection or dialogue—much less the sustainability of the current entente between the two groups—is possible.

To comment on this article, please write to jnbs@stu.ca.

Si vous souhaitez réagir à cet article, veuillez soit nous écrire à jnbs@stu.ca.

Marc-André Bouchard is a graduate student in linguistics at the Université de Moncton and a research technician at the Laboratoire d’analyse de données textuelles.

Sylvia Kasparian is Professor of Linguistics at the Université de Moncton and Director of the Textual Data Analysis Laboratory.

Notes