Invited Essays

Definitely Maybe:

A Recent History of Electoral Reform in New Brunswick

Introduction

1 Electoral reform in Canada has been characterized as a policy area with a small, committed, and loud group of reformers and a large, apathetic, and relatively content public. The policy initiatives of reformers have rarely captured the imagination of the public-at-large (Carty 2004). The long history of sporadic electoral reform attempts throughout Canadian political history was accelerated in the mid-2000s with a combination of disruptions. Prime Minister Paul Martin declared a “democratic deficit,” observers noted the deference of Parliament to the executive, and half of the provinces were examining their electoral system (Carty 2004). These events were notable because a major part of the electoral reform story in Canada has been the reluctance of parties in power to change the system that helped them win elections. This paper will examine how leaders in New Brunswick communicated electoral reform to the public when making a conscious decision to initiate electoral reform policy discussions. Leaders’ clear and public support is significant in electoral reform efforts based on recognized barriers to reform in the past: a lack of information for the public, negative media discourse, and the difficulty of referenda (Cutler et al. 2008; LeDuc 2009). Due to these contextual and structural challenges faced by reform advocates, the dominant role political elites occupy in Canadian federal and provincial political systems provides elites with a unique opportunity in the electoral reform policy process.

2 Since most modern Canadian first ministers have led centrist or brokerage parties that benefit from the vote-to-seat calculations of plurality electoral systems, there is little gain seen in switching to a proportional system. Considering this, the enthusiasm or conviction expressed by leaders of major parties is notable when examining the likelihood of electoral reform—a likelihood that has increased with a flurry of electoral reform initiatives by Canadian federal and provincial governments since the turn of the century. When it comes to the electoral reform initiatives reaching their near conclusion, the response of political elites can be telling. There is a pattern of ambivalent rhetoric from Canadian first ministers in reaction to failed electoral reform initiatives.

3 In New Brunswick, the electoral reform pledge predicament is unique because of the role of the two major and dominant parties in the policy debate’s recent history. In the last two decades both the Progressive Conservative (PC) and Liberal parties have considered electoral reform after forming government, an unusual policy move since the current electoral system played a central role in helping them gain power. While the Liberal case is still in process at the time of writing this paper, the policy cycles of both PC and Liberal efforts to reform the electoral system reveal a rhetorical ambivalence. As well, New Brunswick has been idealized as an appropriate case study for analysis because of its depiction as a “microcosm” of Canada (Cross 2007, 13). To date, most work on electoral reform in New Brunswick has focused on the issue of electoral boundaries and the province’s pragmatic approach to reform (Campbell 2007; Eagles 2007; Hyson 2000).

4 In the aftermath of the most distorted first-past-the-post (FPTP) results in Canadian electoral history (the 1987 New Brunswick provincial election), both the PC and Liberal parties considered electoral reform. Yet both parties showed reluctance and reticent rhetorical support of the policy initiatives. Without rhetorical political support, it is difficult for government to instill enthusiasm for reform in a policy area that for many citizens and stakeholders is not a ballot box priority. Democratic reform initiatives need political elite champions who not only usher in policy but provide rhetorical cues and an education to constituents. However, the hedging of supportive language coming from dominant political parties should be no surprise in public policy debates concerning the shift from plurality to proportional electoral systems.

5 In this paper, I consider the words and roles of political elites, both premiers, cabinet ministers, leaders of the opposition, and opposition critics. I do not focus on the merits of one electoral system versus another but rather focus on the political rhetoric and its role in the electoral reform policy process. Using the Infomart database of Brunswick News daily newspapers (Fredericton Daily Gleaner, Moncton Times and Transcript, Saint John Telegraph-Journal), the time period of 1998 (the start of the database) to 1 November 2017 was searched using the term “electoral reform” to track newsworthy comments and actions of New Brunswick political parties and elites on electoral reform. Once this search was completed, the most notable political comments and actions were fitted to Anthony Downs’s issue-attention policy framework to track policy rhetoric and action on electoral reform in the province. The framework is used to organize the recent chronology of actions and discourse surrounding electoral reform in New Brunswick. Using this evidence and framework, I argue that recent electoral reform efforts in New Brunswick have been dominated by ambivalent rhetoric from the Progressive Conservatives and Liberals, both in and out of power, contributing to a lack of policy and political momentum on electoral reform.

The Analytical Framework

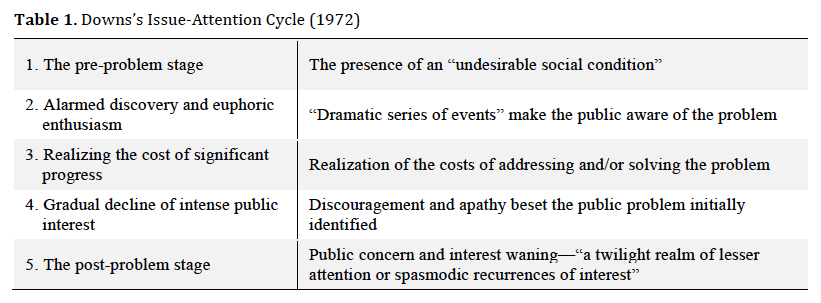

6 Cited thousands of times by researchers, Anthony Downs’s “issue-attention cycle” is a useful analytical framework for public problems and government policy (1972). Downs’s study focused on environmental policy in the United States but is still a valuable tool for considering any public policy endeavour. Downs’s cycle has five stages, which are listed with paraphrased descriptions for each in Table 1.

7 For this paper, the issue-attention cycle is applied to periods of electoral reform in New Brunswick involving PC and Liberal governments. The time frame covers the initiation of electoral reform by the Bernard Lord PC government to the Brian Gallant Liberal government announcement of a 2020 referendum on preferential ballots. The time frame is analyzed using the issue-attention cycle and divides the rhetoric and action or inaction of the electoral reform policy process into the five stages starting after the 1987 provincial election results: 1. Pre-problem (1987–1999), 2. Discovery and process (1999–2007), 3. Realizing cost (2007), 4. Declining interest (2007–2016), 5. Post-problem (2016–2017).

1. The Pre-Problem Stage (1987–1999)

8 Downs describes the pre-problem stage as having the presence of an “undesirable social condition.” Typically, with elections, the undesirable social condition is the supposed inaccurate reflection of the electorate’s will in the composition of a legislature. This condition is defined subjectively—while there may be critics of the legislative results, there is not an absence of supporters of the status quo and the FPTP system in Canada. One of the common complaints about the effectiveness of the FPTP system is when it produces a gap in parties’ popular vote and representation in the legislature. For example, in 2006, the New Brunswick PC party edged out the Liberal party by 0.4 per cent of the popular vote but the Liberals formed a majority government (twenty-nine seats to twenty-six seats). Yet in New Brunswick, the results of the 2006 provincial election appear as a rounding error compared to the 1987 debacle—the Liberal sweep of the legislature. Two days after the Liberal party’s 58–0 shutout of the provincial legislature, the front page of the Globe and Mail read “Shock, Wonder Greet N.B. Vote” (Fagan 1987). The 1987 New Brunswick provincial election results would become the most often cited distortion of the FPTP electoral system for advocates of electoral reform in Canada. The Liberal party win brought an end to seventeen years of PC rule but the more historic numbers were 59 and fifty-eight—59 per cent of the popular vote to win all fifty-eight seats in the New Brunswick legislature. The push for electoral reform in New Brunswick was propelled, however delayed, by the 1987 results (Cross 2005).

9 While Kenneth Carty suggests that in a jurisdiction’s pursuit of electoral reform “there is no common catalyst…[each] reflects a different local story” (2004,176), William Cross suggests three factors that played a role in British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Ontario— “disproportionality, widespread democratic malaise and a desire by governments to be seen as reformers” (Cross 2005, 76). Notably in New Brunswick, based on the ambivalent rhetoric from political elites, it is unclear which one of these factors played a role in the province’s exploits in electoral reform. While the 1987 election clearly presented a case of disproportionality, it took over fifteen years for a government to launch an examination of the electoral system. Considering the lack of broad public outcry against the status quo, both in the tempered enthusiasm for electoral reform and continued overwhelming support of the two traditional parties, it is difficult to suggest that a state of “widespread democratic malaise” existed in the province. Cross’s suggestion that there is the presence of “a desire by governments to be seen as reformers” fits best with the New Brunswick experience— after all, “being seen” as reformers does not require results, just intentions. Cross notes that while premiers struggle at constructing long-lasting reform through education or health care policies, they are able to build political legacies through democratic and electoral reform. In New Brunswick, the rhetoric of political elites provides evidence of political legacy building.

10 While not addressing the electoral system between 1987 and 2003, the government did investigate electoral redistricting through the New Brunswick Boundaries Commission, which submitted its final report in 1993. The commission’s mandate called for an investigation of the electoral boundaries and normative representational issues, and produced considerable discourse on New Brunswick elections—or, as Stewart Hyson put it, “a sea of ideas” (2000, 190). Still, the commission’s focus and eventual report was on boundary redistribution and not how individuals were elected. One of the unintended legacies of the commission was to set a precedent for public input on changes to elections and the availability of bilingual services at public forums for a province with two official languages. By 2003 the PC New Brunswick government would turn its attention to electoral reform and initiate a major policy investigation.

2. Alarmed Discovery and Significant Progress (1999–2007)

11 In this stage, Downs describes a dramatic series of events and a new level of public awareness. In addition, at this stage, the public demonstrates an enthusiasm to solve the problem. There is confidence that a difference can be made. In the case of the New Brunswick electoral reform policy cycle, the “dramatic” events had occurred over a decade earlier with the 1987 and 1991 elections and their distorted results. Still, New Brunswick Premier Bernard Lord spoke of reforming the province’s democracy over a decade later, announcing the creation of the Commission on Legislative Democracy in December 2003. Lord stated, “Democracy is the most fundamental expression of who we are and how we live. We want to ensure that our legislative democracy in New Brunswick is truly citizen-centred, that it represents all residents of our province” (qtd. in McGinnis 2004). Lord’s rhetoric was significant, focusing on the state of democracy in the province and a concern for effective representation in the legislature. The eight-member commission was provided the following mandate: “To examine and make recommendations on strengthening and modernizing [the] electoral system and democratic institutions and practices in New Brunswick to make them more fair, open and accessible to New Brunswickers” (New Brunswick 2004, 77). The Lord government tasked the commission with investigating three areas—electoral reform, legislative reform, and democratic reform—and under electoral reform to consider and make recommendations concerning the implementation of proportional representation (McGuigan 2004).

12 In 2004, the commission recommended mixed-member proportional representation with thirty-six constituencies and an additional 20 MLAs. The response across the legislative aisle was lukewarm. Liberal house leader Kelly Lamrock stated,

Lamrock’s “waste of time” narrative would be repeated by critics from both parties at various stages of the election reform policy cycle.

13 Lord followed his earlier rhetoric with action, albeit somewhat delayed. In response to the commission’s report, the government pledged to hold a referendum on 12 May 2008 to coincide with municipal elections. Yet even with the decision to commit to a referendum, Lord’s rhetorical support was restrained. Lord admitted to favouring a mixed-member model of proportional representation, but also noted:

Lord also supported a 50 per cent threshold for a “yes” result, unlike the 60 per cent threshold used in Prince Edward Island and British Columbia referenda. During a speech to the Canadian Study of Parliament Group, Lord defended the use of a referendum: “The final say would have to be with the citizens. I could not see us changing the system by how people vote and elect their governments without having the people decide that” (qtd. in Morrison 2004). The actions and rhetoric reflected progress for advocates of electoral reform; the government had set the path to a decision-making process on the future of the New Brunswick electoral system.

14 With the government’s actions and Lord’s stated positions, this period could be described as the peak of enthusiasm and confidence for some type of electoral system change. For groups that advocate for electoral reform such as Fair Vote, the developments with the PC party in power reflected significant progress. There was a referendum date set and a question on moving to a mixed-member proportional system was scheduled. For supporters of reform and the PC government, the coming years would be filled with unexpected turns in the policy cycle and the loss of government power.

3. Realizing the Cost of Significant Progress (2007)

15 In Downs’s third stage of the cycle there is a realization that solving the problem involves cost. Considering the Progressive Conservatives benefitted from a plurality system on most occasions, it is surprising that the electoral reform policy cycle made it to a referendum question and set date. The risk of putting the date of the referendum to 2008 was easy to see in the legislative standings. When Premier Lord made the commitment to tying the referendum to the 2008 municipal elections, he only had a one seat majority in the legislature. Any sort of unintended or unexpected changes to party standings could have a grave impact on the life of the government and possibly the plans for a referendum. On 17 February 2006, this unexpected event occurred when the member for Miramichi–Bay du Vin decided to sit as an independent. The clock started ticking to the next election, and on 18 September 2006 the Shawn Graham Liberals replaced the PCs as the government. Within a year, the new Liberal government had scrapped plans for a referendum. Liberal government house leader Stuart Jamieson said, “We didn’t like the idea, we felt that people in New Brunswick want to elect their representatives in the province. We are not a party that really agrees with referendum. We are a party that is elected to make decisions and we felt this was a decision we could make” (qtd. in Robichaud 2007). This rhetoric was not ambivalent; when parties or governments supported the electoral system status quo, it was with greater clarity and enthusiasm than discussion of change.

16 The Liberal party’s position once in government should not have come as a surprise. In opposition, as the PCs were going down the path of electoral reform, the opposition frontbenches did not support electoral system change. Liberal Kelly Lamrock warned that a mixed-member proportional system would create “Frankenstein MLAs” (Daily Gleaner 2004) and argued, “The premier told this commission they had to recommend proportional representation. Here we have a model that is going to be absolutely impossible for people to understand” (qtd. in Moszynski 2005). Now in opposition, the PCs defended their efforts. Opposition house leader Bev Harrison responded that “I think our first-pastpost system is not appropriate for a sophisticated, educated public who are more and more conscious of what governments are doing and members are doing” (qtd. in Robichaud 2007). Regardless of PC protests, the Liberals turned the clock back on the electoral reform policy cycle after the previous government had appointed a commission on legislative democracy. The commission recommended electoral reform and the government committed to a referendum on electoral reform. By the end of 2007, the policy cycle was stalled, the policy momentum stopped.

4. Gradual Decline of Intense Public Interest (2007–2016)

17 At stage four, Downs suggests the opportunities of stage three transform into challenges and declining interest in the policy problem. Between 2007 and 2016, plans for electoral reform were rarely publicly expressed by governments or opposition parties. A closer examination of official political and policy communications reveals the decrease in interest from the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives over this period as both parties took turns forming the government, with a Liberal majority government from 2006 to 2010, a Progressive Conservative majority government from 2010 to 2014, and a Liberal majority government again from 2014 to 2018.

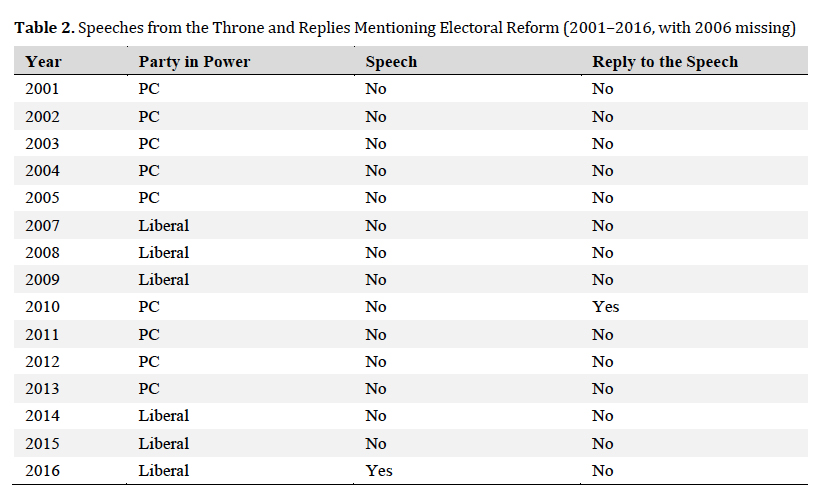

18 Two key political documents for political parties are election platforms and speeches from the throne or replies to speeches from the throne. A review of recent platforms and speeches reveals the lack of sustained political and governmental attention that the Liberal and PC parties in New Brunswick placed on electoral reform during the time period under examination. First, when considering speeches from the throne and replies to speeches from the throne we find only two mentions in the last fifteen years (from thirty texts, both speeches and replies). As seen in Table 2, electoral reform was raised by the Liberals in their response to the 2010 PC speech from the throne and again by the Liberals in their own 2016 speech from the throne. Speeches from the throne are considered as the text where the government presents its plans for the upcoming session, and as is seen in the speeches and replies from 2001 to 2016, electoral reform was rarely in the government’s plans or on the opposition’s radar.

19 In the Liberal party’s 2010 reply to the speech from the throne, interim leader Victor Boudreau argued, “Let’s not tear up the playbook, but let’s show some respect for the electoral system under which New Brunswickers believed they were operating” (qtd. in New Brunswick Liberal Party 2010). A year later, opposition house leader Bill Fraser placed the onus of change on the population: “It’s going to be up to the people of New Brunswick what type of system they want and the government’s going to have to reach out to the people of New Brunswick to see what type of reforms they would like to see” (qtd. in Huras 2011). Again, we see an absence of commitment to electoral reform through ambivalent policy rhetoric.

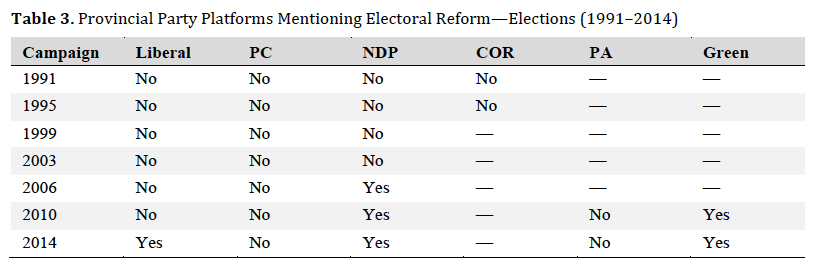

20 Another occasion where a political party leaves a rhetorical record is their campaign platform. Not only do platforms provide a snapshot of pressing issues at the time of an election, but also provide a listing of a party’s policy and political priorities. As seen in Table 3, New Brunswick’s two major parties rarely include electoral reform as a political or policy priority in campaign platforms.

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2 Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 321 Seven years after scrapping the Lord government’s plan for a referendum on electoral reform, the Liberal party included the following noncommittal promise in their 2014 election platform: “[Investigate] means to improve participation in democracy, such as preferential ballots and online voting” (New Brunswick Liberal Party 2014, 37). For some, this may have come as a surprise based on the Liberal’s discourse in opposition, which did not foreshadow any attempts at electoral reform since the Graham government stopped referendum plans in 2007.

22 Not surprisingly, the campaign platforms of minor parties such as the NDP and Green party pledged electoral reform (NDP 2006, 2010; NB Green Party 2010). Somewhat surprisingly, though, the NDP leadership has been ambivalent about electoral reform in recent years. Party leader Dominic Cardy was concerned that advocating for electoral reform appeared to be an excuse for the lack of NDP electoral success and legislative representation. In 2013, Cardy said, “The New Democratic perspective is we have to win an election using the current system. We don’t want to see the system changed to make it easier for us to win seats” (qtd. in Chilibeck 2013). This was a sentiment Cardy had expressed in the past. After the 2010 results, Cardy, the NDP campaign director at the time, said about electoral reform, “It tends to sound like the kid who claims he would’ve won the soccer game if only the rules had been different. It sounds a bit like sour grapes. At the end of the day, the more the small parties push for proportional representation, the easier it is for the big parties to ignore it” (qtd. in McMahon 2010). Cardy contradicted the party’s campaign platform positions, which in 2006, 2010, and 2014 included pledges to pursue electoral reform. Notably, Cardy’s language is similar to the ambivalence found in rhetoric from Liberal and PC party leaders and elites.

5. The Post-Problem Stage (2016–2017)

23 In Downs’s fifth and final stage, he describes a state of “limbo,” “lesser attention,” and “spasmodic recurrences” (1972, 40). In the 2014 election campaign and aftermath, electoral reform was in limbo due to the Liberal government’s fraught legislative relationship with the PC opposition and a less-than-ideal policy rollout. Following their 2014 election campaign pledge, the Liberal 2016 speech from the throne announced that the government “will also receive and respond to recommendations on electoral reform” (16). The PC party dismissed the effort, saying “The history and actions of this government have not been good at all, and now if they go and say we want to change the way people vote, you can be darn tootin’ it’s going to favour the Liberals” (interim PC leader Bruce Fitch, qtd. in Chilibeck 2016a). The Liberals planned to proceed from the discussion paper to form a select committee on electoral reform to publish hearings, with recommendations in January 2017. The opposition PC party refused to sit on an all-party committee to consider electoral reform, blaming the behaviour of the governing Liberals and composition of the committee (majority Liberal). In response, the Liberal government created an independent commission, gave it terms of reference, and appointed five members. At the same time, the Gallant government reached out to PC party leadership contestants, without success, encouraging them to participate in a select committee on electoral reform (Chilibeck 2016a). In the backdrop of this timeline was the federal Liberal government’s fledgling efforts to pursue electoral reform. The federal situation was notable because the Gallant Liberals are closely aligned with the Trudeau Liberals; federal minister Dominic LeBlanc served as chair of Gallant’s Liberal leadership bid.

24 Victor Boudreau, who led the electoral reform file for the Liberal government, wrote in a 2016 editorial:

Boudreau’s language reflected that of Lord’s over a decade earlier, raising concerns about the province’s democracy and suggesting that improvements could be made. Considering the parallel challenges of legislative democracy the government was experiencing, Boudreau’s sentiments may have sounded disingenuous to some. Still, it is notable that the same type of altruistic democratic rhetoric was adopted at this point in the electoral reform policy cycle.

25 The Liberal house leader, Rick Doucet, added to the government’s message by providing evidence of a system needing improvement, citing voter turnout in recent municipal elections and connecting this to their electoral reform effort:

Doucet’s comments reflected a policy reversal for the Liberal party from when they opposed a similar PC effort as a waste of time. In 2011, Liberal opposition leader Boudreau said of proportional representation, “I think there are bigger issues to deal with right now. I can’t help but wonder why, if it’s such a great system, nobody in Canada has it” (qtd. in Berry 2011). Boudreau’s sentiment at the time matches the 2016–2017 position of the PC party.

26 When the New Brunswick Commission on Electoral Reform tabled its report in 2017, its recommendations and discourse reflected the previous path of moderate reform proposals. The commission made two recommendations on changes to the voting system: first, that the government enhance the voting system by moving to preferential ballots, and, second, that consideration be given to some form of proportional representation during the process of considering the redistribution of electoral boundaries (NB Commission on Electoral Reform 2017 19). The commission defended the preferential ballot recommendation: “This is a modest, pragmatic choice for reform that does not create its own series of problems, as a wholesale change to another electoral system would. It also keeps things simple and easy, so that everyone can understand how to vote and that their vote really counts” (18). The response to the report focused more on other recommendations than those addressing the electoral system. The recommendation to lower the voting age to sixteen years old produced more reaction than anything to do with FPTP or preferential voting. Still, the premier’s response to the headline item was tempered, an ambivalence reflecting the political elite rhetoric on electoral reform in New Brunswick. On lowering the voting age, Gallant said, “I think it goes with a goal that many New Brunswickers have to have more people voting. There’s no doubt it would have a significant impact on the number of people able to vote, so we have to take some time to think about that and to look at how we will respond as a government” (qtd. in Bissett 2017). Notable in Gallant’s language is the expression “many New Brunswickers” rather than the “government” as well as a declaration that more deliberation and time are needed, again a common theme throughout New Brunswick’s electoral reform adventures.

Conclusion

27 While I argue that New Brunswick’s recent history on electoral reform fits well to Downs’s framework, Downs suggests that not all public problems fit the issue-attention cycle. Downs’s model focuses on social problems, and he suggests the problems that fit the cycle should exhibit some of the following characteristics:

These characteristics fit New Brunswick’s recent electoral reform explorations. First, in New Brunswick’s two-party system, a majority of voters may not believe they are suffering from the FPTP system. Since 1987, 84 per cent of New Brunswickers have voted for Liberal or PC candidates. Moreover, 97 per cent of elected representatives since 1987 have been Liberal or PC candidates. While Liberal and PC governments have both initiated formal discussions on electoral reform, neither party or its supporters, which reflect the wide majority of political actors in the province, necessarily “suffer” from any subjectively defined public problem. Second, and clearly connected to the first characteristic, any problems considered to have been created by the FPTP system benefit the Liberal and PC parties and the majority of New Brunswick voters. Middle-of-the-road, centrist, brokerage parties benefit from plurality electoral systems. Third, the exciting qualities of the problem that peaked in 1987 or 1991 have not been replicated to the same extent as those dramatic Liberal electoral landslides. The 2014 results provided some “excitement” in terms of more notable disproportionality, as 23 per cent of New Brunswickers did not vote for the Liberal or PC candidates, more than double the percentage of New Brunswickers who voted for non-PC or non-Liberal candidates in 1987.

28 By tracking the ambiguous and ambivalent attention, the case is made that electoral reform in New Brunswick has been much more aspirational than concrete. Considering that both the Liberal and PC parties would most likely not benefit from a move to proportional representation through a multimember proportional system or single transferable vote, the largely (and merely) rhetorical actions fit well with one of William Cross’s factors for electoral reform: the desire to be seen as reformers (2005). The lack of consistency in positions on electoral reform over the two decades suggest less of a policy push and more of policy positioning. The parties traded places on reform versus the status quo, and seemed to alter their positions on the need or scope of consultation on change and the timing of change. Still, the evidence suggests that electoral reform is an aspirational rather than realistic policy goal, at least for the political class.

29 The 2020 plebiscite that will take place at the same time as municipal elections will ask voters two questions: first, should people as young as sixteen have the right to vote, and, second, should New Brunswick move to a preferential ballot system in future elections? The timing of the referendum places the Liberal government in an even more precarious position than that of the Lord government more than a decade ago. While the Lord government did not expect to be facing the electorate before being able to follow through with the referendum plans, the Gallant government is guaranteed to face the electorate before the planned referendum. Justifying the gap in time, Victor Boudreau argued that “We also want to give the public ample time to understand the choices available especially with respect to changes such as a preferential ballot” (qtd. in Chilibeck 2017).

30 It is difficult to predict how this gap in time will affect the political conditions surrounding the proposed 2020 vote. The revolving-door, turnstile government that the twenty-first-century New Brunswick political climate finds itself in may be an obstacle to either of the two major parties clearly addressing electoral reform through commitment to change, or it may mean the abandonment of reform talks altogether. As well, the results of the 2018 provincial election could have a major impact regardless of which party forms government. If parties such as the NDP and Green see their popular vote grow (it was 19.6 per cent combined in 2014) without growth in legislative representation, this could add evidence to the case of reformers. As well, unfolding political events in other provinces could influence the New Brunswick situation. In October 2017, the British Columbia government announced a referendum on electoral reform in 2018. BC New Democratic Premier John Horgan described FPTP as unfair, and promised to campaign in support of proportional representation (Meissner 2017). Horgan’s language and timetable were clear, and the New Democratic party is one of the central parties in British Columbia. Time will tell if Gallant will follow John Horgan’s path as 2020 approaches, or if there is a continuation of ambivalent rhetoric from New Brunswick political elites, and the province’s electoral reform cycle will continue into perpetuity.