Refereed Articles

HIV and the Health of Women in New Brunswick

This study focuses on the marked similarities in experiences of women living with HIV/AIDS in New Brunswick. The narratives of these women demonstrate the resilience shown in the face of HIV infection, the challenges associated with accessing HIV care services, and the profound stigma that the condition has on their lives after diagnosis. I further show how local AIDS service agencies play an important role in reducing stigma and discrimination in the community by offering special initiatives in the province to create awareness and support people living with HIV.

La présente étude porte sur les grandes similitudes avec ce que vivent les femmes atteintes du VIH-sida au Nouveau-Brunswick. Les histoires de ces femmes montrent leur résilience face à l’infection du VIH, les défis liés à l’accès aux services de soins du VIH et la profonde stigmatisation que leur trouble de santé a sur leur vie après avoir obtenu le diagnostic. De plus, elle montre à quel point les organismes de services liés au sida de la région jouent un rôle important dans la réduction de la stigmatisation et de la discrimination dans la collectivité en offrant des initiatives spéciales dans la province afin de sensibiliser les gens et d’appuyer les personnes vivant avec le VIH.

Introduction

1 Women in Canada, until recently, have been invisible in the medical system and absent from the HIV/AIDS research agenda, which has led to misdiagnosis and delayed entry into HIV care and treatment (Nova Scotia Advisory Council on the Status of Women 5). While all women are potentially at risk for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, disproportionately high levels of HIV infection are found among specific groups, including young women; women who use drugs; trans women; women involved in sex work; and African, Black, Caribbean, and Aboriginal women (Public Health Agency of Canada, “Status of HIV/AIDS” n. pag.). A number of different factors contribute to women’s vulnerability to HIV, such as gender inequalities, lower education level, challenges accessing services in rural area, unemployment, substance use, migration and mobility, and fear of positive status disclosure (Bourassa and Bulman 8–10; Bulman 84–89; Gahagan et al. 21–22; Public Health Agency of Canada, “Population-Specific HIV/AIDS” v). These inequalities in health not only place women at a higher risk for HIV infection, but also reinforce isolation resulting from a positive diagnosis (Gahagan and Ricci 8).

2 The prevalence of the HIV infection in Canada has steadily increased by 9.7 per cent since 2011 (CATIE, “The Epidemiology” par. 3; Government of Canada). Women comprise a significant proportion of people living with or at risk of HIV infection in Canada, accounting for 22.4 per cent or 16,880 of all reported cases (CATIE, “The Epidemiology” par. 12; Government of Canada par. 11). Transmission continues to be predominantly through heterosexual contact (59.7%) and injection drug use (35.4%), and highest for persons between the ages of fifteen to forty-nine in spite of enhanced HIV testing services and care (Archibald and Halverson 7–8; Public Health Agency of Canada, “HIV/AIDS Epi Update” par. 6). The Public Health Agency of Canada (“Summary: Estimates of HIV” 4) estimates that 21 per cent of individuals are not aware of their positive HIV status, which underscores concerns that barriers to testing and diagnosis may still exist in parts of the country.

3 There has been very little written on the experiences and health of women living with HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in New Brunswick (Bourassa and Bulman; Bulman [“A Constructivist,” “Learning about HIV/AIDS”]; Carr and Gramling; Nicol and Butler; Olivier and Stanciu). New Brunswick provides an optimal setting to conduct an intensive case study because of the remoteness of its communities and relatively low prevalence of HIV cases, especially among women, who account for 13.7 per cent of all cases in the province (Public Health Agency of Canada, “Summary: Estimates of HIV” 42–43). Province-wide assessments produced by the three AIDS service organizations—AIDS New Brunswick, AIDS Saint John, and AIDS/SIDA Moncton—and the academic works of Donna Bulman, Professor of Nursing at the University of New Brunswick, and Margaret Dykeman, retired member of the Faculty of Nursing at the UNB, provide interesting insights into women’s specific experiences in the province. Their reports were essential in developing my research design. This study specifically builds on the previous work of Bulman (“A Constructivist,” “Learning about HIV/AIDS”) by collecting women’s narratives, and focuses on the struggles and resilience of women living with HIV for five years or longer who regularly access social services from HIV/AIDS agencies. The material in this article is drawn from my master’s research focused on the experiences of six women in the province. It explores the narratives of women living with HIV to establish how they make sense of the stigmatized identity associated with HIV infection and talk about their HIV status in the broader context of their life history. Important differences exist within this group according to health status, income, education, and occupation. However, marked similarities also emerge in the reflected stories, including the resilience shown in the face of HIV infection, challenges associated with accessing HIV care services, and the profound impact that stigma continues to have on these women. The article concludes with the contributions this research makes, highlighting the need to improve existing programs to reduce stigma and suggestions for how to better support women living with HIV to overcome challenges in their lives.

Background of HIV and AIDS in New Brunswick

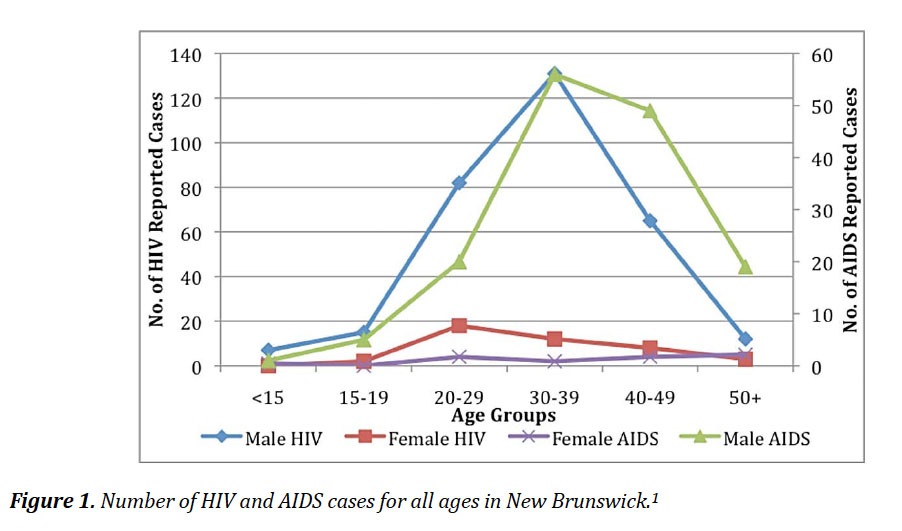

4 The first reported case of a woman living with HIV in New Brunswick was reported in 1983, one year after the first detected case of AIDS in Canada (CATIE, “A History of HIV/AIDS” par. 2–3). There are a total of 611 people living with HIV and AIDS in New Brunswick to date; most cases are identified among injection drug users and men having sex with men (Public Health Agency of Canada, “Summary: Estimates of HIV” 42–43). Figure 1 illustrates the most recent number of HIV and AIDS cases for persons in the province.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

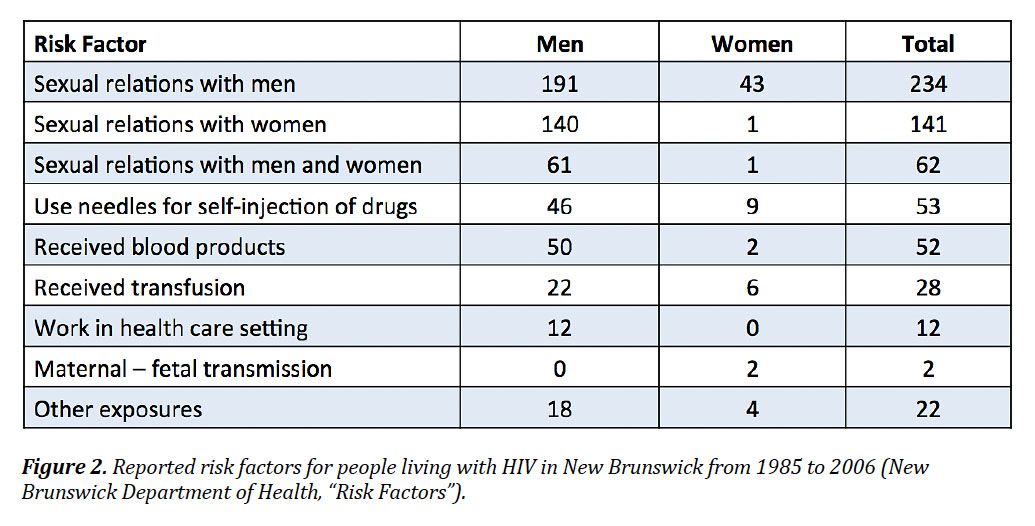

5 Estimates of new HIV infections are on the rise in the province among women due to unprotected sexual intercourse and substance use, particularly heroin, opiates, and crack. The majority of new HIV diagnoses among women in the province are correlated with heterosexual contact (Colman 202). Figure 2 highlights the total number of persons living with the HIV infection by gender. Women in New Brunswick between the ages of twenty and thirty-nine account for less than 30 per cent of all new HIV diagnoses in the province. This number is steadily rising partly due to the delay of HIV diagnosis later in life and changes in sexual behaviour practices that increase one’s risk to HIV infection (New Brunswick Department of Health, “Risk Factors”).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

6 It is important to note that Figures 1 and 2 illustrate only those that have tested positive for HIV and AIDS. More readily available HIV testing services at AIDS service agencies, including AIDS New Brunswick in Fredericton, creates a new and difficult challenge of reporting related data to the Public Health Agency of Canada due to privacy issues (Gahagan and Proctor-Simms 3).

7 The province-wide assessments produced by the three AIDS service organizations (AIDS New Brunswick, AIDS Saint John, and AIDS/SIDA Moncton) are important pieces of data in better understanding the experiences and health of women living with HIV. Olivier and Stanciu’s community report on the impact of the changing epidemic in New Brunswick was important in identifying the systemic social and health problems of people living with HIV (4–5). This was the first assessment to examine the health of people living with HIV and AIDS in New Brunswick. Nearly half of the participants who took part in the project reported travelling 150 kilometres to see an infectious disease specialist, which presents a major barrier to accessing care and treatment (Olivier and Stanciu 27). Housing stability was another significant finding from the assessment. Twenty per cent of persons living with HIV/AIDS described inadequate housing conditions and complete dissatisfaction with their current living situation as reasons for poor access to social service agencies, heighted stigma, and self-isolation (18). Results from the report supported the efforts of AIDS service organizations to improve the availability of an emergency response fund to offset costs associated with a positive HIV status and enhance relations with local farmers and food producers to better the nutrition of people with this disease.

8 A second community assessment coordinated by Nicol and Butler further explores the experiences of stigma, discrimination, care, and support of people living with HIV/AIDS in New Brunswick (1–2). Concerns regarding transportation barriers to health care and the degree of health among people living with HIV/AIDS echoed findings in the 1999 report, and reinforce key social problems that AIDS service agencies continue to address. The high cost of travel to health and social services is a significant barrier for people to access HIV care and treatment. Of the twenty-three participants, 61 per cent were travelling one and a half to four hours (round trip) to Moncton or Saint John to see an infectious disease specialist. Thirty-five per cent of the participants explain the need for additional support materials on issues surrounding lifestyle changes and aging, support services that are absent from the New Brunswick care continuum (Nicol and Butler 15).

9 Another provincial report by Bourassa and Bulman in the same year focused on the quality of life among women living with HIV and AIDS in the province by centring on providing better access to health information and resources (8). A startling finding was not only that most female injection drug users were between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four, but that women were sharing drug equipment with partners because of fear of rejection, violence, and abandonment of relationships (14). A secondary finding was that most of the women preferred gathering health information about HIV and AIDS in the following order: infectious disease specialist, doctor, nurse, sexual health centre, hospital or clinic, and AIDS service agencies (53). This was important to AIDS service agencies and used to inform special initiatives in the province to create awareness and support people living with HIV, including the expansion of community networks and emphasis on school-based health education.

10 Donna Bulman’s work on the health of women living with HIV in New Brunswick was the most recent that influenced my own research in 2010. The objective of her work was to gather the shared beliefs, perspectives, and experiences of women living with HIV in the Maritimes, and to learn how to increase AIDS awareness through education ( “Learning about HIV/AIDS” vi). Two focus group discussions were held with the forty-four participants as a way to compile a list of barriers people experienced when accessing community services, including stigma and discrimination, social isolation and ridicule, lack of culturally appropriate and available services, fear of HIV testing and care, and poverty (viii). Results from the study were important in underscoring the need for more women-centred care services rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. Her work pointed to the need for an up-to-date assessment to better understand the changing gendered landscape of HIV and AIDS in the province. My study was designed to use similar methodologies to expand on the work of Bulman and analyze the narratives of women living with HIV.

Methods

11 Prior to starting fieldwork, my study was given ethical clearance by the University of New Brunswick and the Horizon Health Network Research Ethics Board. Obtaining provincial research ethics in New Brunswick provided me with clearance to post recruitment materials in municipal health clinics. Data were collected from June 2011 to February 2012 with the help of the three AIDS service agencies: AIDS New Brunswick, AIDS Saint John, and AIDS/SIDA Moncton. Figure 3 is a map of where the multi-site project took place in the province.

Display large image of Figure 3Map key: 1. AIDS New Brunswick. 2. AIDS Saint John. 3. AIDS/SIDA Moncton.

Display large image of Figure 3Map key: 1. AIDS New Brunswick. 2. AIDS Saint John. 3. AIDS/SIDA Moncton.

12 A total of twenty-five interview questions were created with the help of the service agencies to ensure study outcomes were relevant to future organizational decision-making procedures and the improvement of support services. All three organizations agreed to post recruitment posters and information brochures in their offices to help me gain access to women living with HIV. Women over the age of eighteen who were living with HIV were selected to participate in the study.

13 One-on-one interviews were held with six women living with HIV. Interviews were sixty to ninety minutes in length and took place in the offices of the AIDS service agencies to ensure the confidentiality of women’s identities and for the convenience for participants.

14 The women were asked a series of questions about the broader context of their life history (e.g., how did you contract HIV, how long have you been living with the disease, did you perceive yourself to be at risk of contracting HIV?), and their personal stories and experiences of living with HIV as a way to measure the impact of this disease on their lives. HIV disclosure was a barrier for many women regarding their participation in this study for fear of rejection, stigma, discrimination, violence, and loss of privacy and confidentiality (despite efforts to provide participants with anonymity by using pseudonyms). For this reason, an intensive case-study approach was used to investigate the experiences and resilience of these women living with the disease.

15 A second series of interviews were undertaken with employees of the three AIDS service agencies and one infectious disease specialist from Saint John to evaluate their perspectives on the experiences of women living with HIV. Pseudonyms were also assigned to these participants to ensure their anonymity and confidentiality in this study. All of the interviews were digitally recorded with the consent of participants to ensure accuracy of the transcribed data. Audio files and transcribed interviews were stored in an encrypted file folder on my desktop computer. The hardcopy of consent forms and other confidential forms were locked in a filing cabinet in my office. Careful note taking, recording, and re-reading of field notes were helpful in identifying important themes and trends in the data.

Narrating the Themes: Voices of the Women

16 Narrative interviews are an important resource in qualitative research from which the broader context of life histories can be transmitted and recorded. The in-depth gathering of information from narrative interviews with women living with HIV contributes to new knowledge that leads to a deeper understanding of just how devastating this disease is to women. Narrative analysis plays a central role in medical anthropology and gives a new understanding to the personal and social experience of illness and suffering (Kleinman 49; Levy 10). Kleinman’s book on illness narratives marks the importance of narratives for medical anthropologists. Medical anthropologists have come to view lived experiences as important because “illness has meaning; and to understand how it obtains meaning is to understand something fundamental about illness, about care, and perhaps about life generally” (Kleinman xiv). Interviewing women and collecting their narratives is essential not only in understanding the construction of self, but also in improving support services delivered by AIDS service agencies. I will present the narratives of women below as they talk about this disease and the impact HIV infection has had on their lives. Women’s responses were organized into general categories of interview content that reflect the ways in which the women told their stories.

Category I: Women Share Their Stories of Living with the Disease

17 The women expressed feelings of shame and self-suspicion when talking about their HIV status in the broader context of their life history because they were sharing their experiences of this disease for the first time to a non-family member. They explained that they do not have a circle of other women friends living with the disease to share their stories because women account for so few cases of reported infection in the province. Collecting the narratives of women living with this disease is important because there has been only one other recording in the province by Bulman. A lot can be gained from women’s stories, including learning more about the impact and consequences of HIV-related stigma and discrimination, and improving current strategies that aim to reduce harms that place individuals at risk for the infection. Women are also largely invisible within the epidemic not only in national and provincial statistics and geographical profiles of the disease, but also in the research more generally (Allen). The experiences and resilience of these women is why their narratives are vital.

Becoming Infected

Three Stories of Heterosexual Transmission

I was just twenty-four and because I was part of a union,…I applied for insurance. They came to my house and took blood and a urine sample. They also took my payment and a month later my payment went back into my bank [account]. I got a letter [in the mail] saying that my test came back abnormal….I thought I might have diabetes because I was tested the year before….I got my sister to [open the letter] and she knew what it said…and told me to come home right away. I knew it was something, but I didn’t think it was HIV….I was only concerned about getting pregnant [and] I didn’t worry about anything else….I’m on the Pill, [so] I’m okay….[When I was tested] I’m like it can’t be [because] I just got tested [a year ago] and it was negative. My partner said he got tested regularly and he was negative….He wasn’t aware that he had it….We were planning on getting married and I want[ed] to go get an AIDS test. When my test came back negative he said we’re in the army, we get tested all the time, but they don’t get tested all the time. His assumption was that they did….I found out by mistake. (Mia)

After meeting his father [we] dated for about probably six or seven months [and] of course he said he was fine. He [said he] was tested before he came over to Canada because apparently you had to be tested before you can come over….I got it from [him] and he didn’t bother to get tested or anything….I made a trip to the emergency [room] that Sunday [because] I had pneumonia and was probably there for two or three days. I went home and I still wasn’t feeling very good so my doctor [told me to] admit myself back to the hospital for another five days until my pneumonia cleared up….He couldn’t figure out what it was [even after] I told him all the symptoms…[but] I think he knew in the back of his head what it was, but he wanted do the cancer [test] first. I got the results back on that [and] it wasn’t cancer….I went out to the receptionist and I just started crying, but I still didn’t know at this point. They took me down to a room to draw my blood….Four or five days later the receptionist called and said that the doctor wants to see me right away….I asked [if I] should prepare myself and she says you might want to….I think in the back of my mind I knew….So it wasn’t a real big shock to me. (Chloe)

Two Stories of Injection Drug Use

I was living in Ottawa at the time [of contraction] and was using a lot of needles….My doctor [tested] two or three times [before] I became positive, so it was just a matter of time….At that point in my life, I just didn’t give a shit about nothing at all. It was just all about the drugs….I even knew that the guy that I was hanging around with had HIV and I used his needle….I took a chance because like I wanted to get high and his needle was the only needle that was available….My addiction was so strong it gets so friggin’ strong that I’ll do anything just to get high. So at that point and time I didn’t care basically….So I came home basically to just get straightened out. (Isla)

One Story of Blood Transfusions

18 The diverse stories told by the women demonstrate a limited perception of personal risk and knowledge about HIV transmission in spite of an increasing testing trend (e.g., opening of the AIDS New Brunswick sexual health testing clinic), numerous educational campaigns, and availability of online prevention information. For example, according to the National Council on the Aging survey, “62 per cent [of 1,300 participants] reported having limited or no knowledge regarding HIV and the behaviours that put them at risk for contracting the virus. This lack of knowledge was not associated with other variables, such as ethnicity, educational level, sexual orientation or viral transmission route” (Nichols et al. 287). A lack of knowledge about HIV transmission speaks to a larger complex problem that is not well understood, but may be connected to HIV-related stigma and discrimination.

19 A Canadian Treatment Information Exchange report states that “since 2003, HIV knowledge has been decreasing, while stigma against people living with HIV has not improved” (CATIE, “Canadians’ Awareness” par. 1). More conservative values in rural areas and beliefs that HIV only happens to other people are factors that contribute to the spread of the disease and are underlying social inequities that perpetuate stigmas (Ontario HIV Treatment Network 2).

Category II: Stigma and How Women Understand the Disease

20 HIV-related stigmas permeated the conversations with all six of the female subjects living with HIV. These stigmas affected how women self-perceived their HIV status (the perception of societal attitudes towards people living with HIV), and affected their encounters with health and social care systems, the community, and society at large. The narratives below show the complex struggle women face with social stigmas surrounding the disease and their own shifting attitudes towards HIV, from a death sentence to a manageable chronic condition.

When you first get diagnosed you feel really dirty. You feel very scared and really you don’t know a whole lot. I remember always looking over my shoulder like something was behind me. It was a really odd feeling….But now as time goes on you don’t feel like…I’m like everybody else. I happen to have a virus….People look at someone like my brother the other day saw this man walking down the street, he was very thin and my brother says [he] looks like he’s dying of AIDS. And so there’s not knowing that he’s sitting with his sister that’s positive….Everyone has that mental image what someone with AIDS looks like. (Mia)

At first I always had this feeling that everyone knew [and that] they were staring at me [like] they know I have it….I wouldn’t face my family cause I was ashamed [and made me feel like I fail[ed] them in some way. Finally my oldest brother called me and he goes you know we still love you no matter what [and that] doesn’t matter if you’re HIV positive [because] we know it wasn’t your fault….Then he said don’t worry, no one knows that you’re HIV positive….You’re just being paranoid about the whole situation. (Chloe)

When I was first diagnosed I thought I’m dying of AIDS. I have this picture in my head of somebody laying in their death bed all sunken in….But that’s not my picture anymore. (Isla)

21 The internalization of stigma can have a profound effect on the prevention, treatment, and care of people living with HIV. Social scientist Erving Goffman defined stigma as a powerful negative label stemming from an attribute that is deeply discrediting (such as HIV), which greatly changes a person’s social identity (4–5). Other researchers have further divided stigma into two kinds: perceived or internal and enacted stigma (Brouard and Wills; Brown et al.; Emlet; Jacoby; Malcolm et al.). Rueda et al. (as cited by Emlet) defines internalized stigma as real or imagined fear that arises from a particular undesirable attribute (such as HIV). Enacted stigma, on the other hand, refers to the actual experience of discrimination (Emlet par. 2). A better understanding of the effects of stigma on women living with HIV in New Brunswick is needed to minimize stigma’s effects, but it is clear in their stories that women who internalize perceived prejudices develop negative feelings about themselves. The advances in medical treatment and medical management of HIV disease are enabling women to survive for many years with what has become a chronic illness; this improves the quality of life for a woman living with HIV and can positively change her perception over time. Samji et al. (as cited by CATIE, “Longer Life Expectancy” par. 5) estimates the life expectancy of someone entering HIV care in 2014 to be in excess of forty years. The following women’s stories reflect their different stages of coping with HIV-related stigma and living with this disease.

I consider it just like any other disease. If you asked me that [question] twenty-five years ago it would have been a different answer. I go on about my business as if I am just like everybody else, and I’m not HIV positive. (Skyla)

It just means I live with a stigma….It means to be fearful if people finding out. (Mia)

It means [you’re] being judged by people. I worry so much about that….For me the big issue behind having HIV is worrying about what other people [think]….It’s not so much that I’m sick, because I’m not sick, right?…I have an immune system that’s pretty much the same as anybody else really, it’s just that I have this disease. A big thing for me is just not letting people find out that I have HIV. It’s [also] a reminder of the damage that I’ve done to my body from my addiction with drugs. (Isla)

22 To protect themselves from stigma, all of the women interviewed relied heavily on their families, AIDS service agencies, and online resources for emotional and psychological support after HIV diagnosis. Spending time with supportive people, especially family members and friends, was a main coping method after diagnosis.

I came home to try to get my life back together again. I’ve done pretty good so far….The relationship [with my family] isn’t the greatest, but they’re supportive....They’ve always been my detox basically, so I’d come home [and] go from one hell and to another hell. (Isla)

23 This finding is contrary to previous studies that HIV stigma in women manifests itself more likely through social rejection and isolation, perhaps because of the challenges of accessing alternate supports in small rural communities (Crossley; Green et al.; Heath and Roadway). Women’s resiliency in spite of how devastating the effects of this disease are may also correlate with participants’ narrative accounts related to aging with HIV disease. While few studies have examined links between resiliency outcomes and the lives of aging adults living with HIV, findings from Emlet et al. suggest that self-acceptance allows individuals to move forward with their lives and against the effects of HIV-related stigma (108). Self-acceptance of one’s HIV-positive status varies, of course, from person to person, and this influences a person’s timing of status disclosure and adherence to treatment. Their will to live in spite of this diagnosis is derived from the general realization that one’s life has a purpose and, in the case of all six women in this study, to financially and psychologically support their families. All six women quit their jobs after HIV diagnosis because of the stigma associated with HIV and the fear of being known to have HIV. After five years or longer of living with the disease and coping with the diagnosis of a chronic condition, four of the women are working part-time, and two gave up on looking for employment due to their fears of pre-employment examinations. These two women are instead accessing many social programs and services (e.g., Social Assistance, clothing and food banks) to improve their health outcomes and meet the needs of their families; both cases are female-headed households that earn considerably less annually (~ $10,000) than the other women in this study. While a woman’s self-perception may change after being diagnosed with HIV, then, stigma and discrimination continue to pose a challenge in their personal lives.

Category III: HIV Stigma and Discrimination Persist

24 Stigma towards people living with HIV is a common phenomenon with far-reaching consequences on people’s health outcomes and relationships. HIV-related stigma and its effects on intimate partner relationships was a common problem all six women talked about in their experiences after diagnosis, especially for the four women over the age of forty. Findings from Psaros et al. similarly support the notion that navigating intimate relationships for older women living with HIV is challenging, especially for women who are managing a chronic illness that is sexually transmitted (755–6). The following narratives describe the complex relationship between HIV and the importance of disclosure to a potential partner.

I’m not sexually active for one….He’s lucky if he gets it once a month….In my relationship that would be one of the main challenges is being close and it could have something to do with working the streets….I’m not letting anybody [get that] close [and] I’m not letting him in [because] I’m afraid of getting hurt again…and I was afraid [of transmitting the infection through] sex. (Tessa)

When I first found out I was positive, my boyfriend at the time tested negative….It was really hard because he was very scared….[With] a new diagnosis you think that’s all you really deserve and you better take what you can get….When I do [date], it’s because I’ve been set up by someone, they just want me to do them a favour….People who are negative look at it just weird [and] I guess it depends on their education or how informed they are about it, but if I had a date, I would choose to date positive because you don’t have to worry about infecting someone. (Mia)

I’ve been going through this relationship stuff that’s just a whole new can of worms, but that’s sorta got me messed up and I ended up using [drugs] because of it….I’m still struggling to find out what I want in a relationship and I tend to always settle….There’s a lot of fear [if] is he going to be the last guy that I’m ever with because I have HIV [positive]…[also] having HIV and being in a sexual relationship is really stressful… because I’m on medication my viral load is undetectable [and] we’ve been using protection, but still there’s that fear that he might get it….I can’t imagine finding somebody else that you have to tell them that you’re HIV positive and all that crap [and] feeling rejection from that. Maybe it’s better for me just get a bunch of cats or something. (Isla)

25 While these women described a fear—namely, the uncertain reaction of a potential partner to the disclosure of their diagnosis—they also felt that they were not worthy in developing or maintaining healthy relationships. Disclosure was often more difficult for women, connected to the far-reaching consequences associated with disclosure. According to Psaros et al, “Participants in the study often managed this by choosing to remain single and trying to ‘focus on themselves,’ suggesting the belief that as an older HIV-positive woman well-being and intimate partner relationships could not coexist” (758). While relationships later in life tend to be of better quality for women living with HIV, persisting stigma and discrimination affects a woman’s ability to meet potential partners largely because of the fear of transmission. Meeting potential partners living with this disease in AIDS service agencies and online settings can reduce the likelihood of stigmatization and help women build a sense of community. As such, local AIDS service agencies are attempting to strengthen their associations with other relevant services women are accessing in the province.

26 Stigma and the perceived consequences of disclosure to family members and friends was also a primary concern for all six women. The need for family support and a concern about protecting family members from HIV infection were the only reasons women felt it was necessary to disclose their status. Although the women detailed legitimate reasons for disclosing their HIV status to family members and friends, some also experienced negative consequences of this action.

I didn’t tell very many and still many don’t know….You get scared that people aren’t going to want your kids to hang out….My son was only in grade 2 [and] my concern was for him at that point, especially him being so young, I didn’t want him thinking he was going to lose his mother….If you’re a parent you put your kids first [because] you don’t want them to be shunned in any way for something that you did. I [also] work [and wonder], would they want to hire me if they knew I was HIV positive cause that’s going to add expense if I get sick…[and] fear of hearing what other people say. (Mia)

27 The relationship between disease progression and disclosure is clearly reflected in the narratives of these women. Serovich et al. suggest that “the disease progression influences disclosure through individuals’ perception of the consequences anticipated as a result of disclosure” (24). For the women in this study, the negative consequences connected to HIV stigma—blame, devaluation, rejection, isolation, and violence—are costs associated with disclosure that may force them to hide their disease from others. Hiding their HIV status from others, however, perpetuates the silence and stigma unique to this disease.

Discussion: Continuing to Talk about Stigma and Women’s Resilience

28 While there has been a shift in the awareness and attitudes of Canadians towards HIV/AIDS, beliefs about the disease as one of promiscuity and immoral behaviour continue to persist and negatively affect women’s access to HIV care (Gahagan and Ricci 34). As a socially constructed response, stigma and discrimination continue to affect women living with HIV and AIDS in New Brunswick in spite of the availability of social supports, school and online education, and progress in treatment.

29 The consequences of HIV-related stigma and discrimination are widespread, as shown in the narratives of women, and include limiting efficacy of HIV testing services and other programs, treatment adherence, and serious impacts on psychological well-being. Carr and Gramling suggest from their own observations that “women themselves no longer believed they were the same women they had been prior to diagnosis….Not sharing the diagnosis with others made the women feel dishonest, but sharing meant pain and rejection” (36).

30 The negative consequences connected to HIV stigma may force infected individuals to delay seeking HIV testing or treatment, hide the disease from others, and fail to adhere to their drug treatment program (Carr and Gramling 37). The fear of stigma also causes denial, isolation, and self-blame, all factors that the six women in this study were struggling to overcome. HIV-infected people, like Peyton and Mia, who fear the negative consequences associated with disclosure, often hide their status from close friends and family members to avoid rejection and isolation. Many people living with HIV fear that disclosure will lead to increased levels of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety, but in fact non-disclosure heightens withdrawal and restriction of social support. Findings from a recent study produced by the Ontario HIV Treatment Network show that persons living in rural areas feel even more stigmatized by the negative social consequences associated with a positive HIV status, which in turn influences the effectiveness of HIV prevention and treatment interventions.

31 These findings are particularly applicable to the HIV and AIDS landscape in New Brunswick. Local service agencies play an important role in reducing stigma and discrimination in the community by offering special initiatives to create awareness and support people living with HIV. Initiatives include one-on-one peer support, emergency response grants, social housing and shelter referrals, accompaniment to medical appointments, on-site sexual health testing, and health information. Providing front-line support to women who have been recently diagnosed with HIV is important, while continuing to build awareness about HIV/AIDS in communities. The three AIDS service agencies in New Brunswick are constantly identifying new strategies to reduce stigma related to living with HIV:

32 The use of these and other strategies is vital in giving the illness a human face to further reduce discrimination associated with the diagnosis. Another strategy is to increase community- and school-based education initiatives to address prevailing stereotypes of people living with HIV/AIDS.

33 Women continue to hide their disease from others partly because they account for so few cases of reported infections; women do not feel safe disclosing their experiences or diagnosis to men. Women would thus benefit from the presence of women-centred programs and services that provide a sense of community and enable those living with the disease to share their experiences of families, treatment, social perceptions, and support. Women-centred services may also improve health outcomes for women by offering them a setting to meet others living with the disease and empower them to make decisions that better manage their own care:

34 While there are no easy or one-size-fits-all solutions to addressing HIV-related discrimination, current stigma-reducing strategies and initiatives provided by AIDS New Brunswick, AIDS Saint John, and AIDS/SIDA Moncton are effective in generating awareness of persisting stigmas in communities. Further understanding of those stigmas through a gendered lens is needed to better address the challenges women face after diagnosis. For example, putting a face to HIV-related stigma could further strengthen knowledge and awareness of this disease, as well as confront community fears about the disease. This is a new approach that the three provincial AIDS service agencies are attempting in order to end HIV discrimination.

35 There were a number of limitations associated with the present study. Establishing trust with women in the community was a key challenge to overcome in collecting their narratives. Despite time and effort spent building relationships with the community and the three AIDS service agencies, some women declined to participate in the study because of health problems, a lack of funds to pay for travel expenses, and a distrust of my intentions as a researcher.

Conclusion

36 Women in New Brunswick share beliefs, perspectives, and experiences of living with HIV/AIDS. This paper uses a case study approach to demonstrate women’s resilience shown in the face of HIV infection, the challenges associated with accessing HIV care services, and the profound impact that social stigmas have on their lives after diagnosis. The findings expose the underlying stigmas towards people living with HIV and the negative consequences these stigmas pose to the health of women with the disease. The presence of strong religious values in parts of the province may make HIV stigma more prevalent in rural communities than in urban areas. This hypothesis—offered by employees of AIDS service agencies—requires further exploration in order to better understand the relationship between HIV-related stigmas and women’s poor health outcomes.

37 Women living with HIV in New Brunswick are managing their health needs effectively by accessing help and support services at AIDS service agencies; however, their narratives demonstrate that not all aspects of stigma and discrimination are addressed in the community. Future research is needed to understand how the lens of gender inequality can influence knowledge and awareness of this stigma and its impact on this disease.

38 Reported cases of HIV infection and other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections in the province are steadily increasing despite the increase in HIV testing and access to health information (Government of Canada). Although women were resilient in their responses to living with HIV, the persisting stigmas around this disease and its emotional impacts were underlying dynamics in their narratives. This study emphasizes that there are no easy solutions to HIV-related discrimination. However, additional funding for AIDS service agencies may enhance the availability of special initiatives that support women coping with this disease.