Refereed Articles

Factors Influencing Family Medicine Resident Retention and Newly Graduated Physicians’ First Practice Location

The New Brunswick Medical Society states that New Brunswick has a shortage of physicians. This study examines retention of newly graduated family physicians from the Dalhousie University family medicine residency sites in New Brunswick from 2005– 2014, and factors influencing physicians’ choices of first practice locations. Approximately half of respondents remained in New Brunswick to establish their first practice. The majority who left New Brunswick to establish their first practice have not returned, whereas most who remained still practice in New Brunswick. Choice of first practice location was influenced by a combination of personal and professional factors. Reasons for leaving New Brunswick were predominantly personal.

La Société médicale du Nouveau-Brunswick affirme qu’il y a une pénurie de médecins. La présente étude porte sur la rétention des médecins de famille nouvellement diplômés du Département de médecine familiale de l’Université Dalhousie qui ont choisi de faire leur résidence au Nouveau-Brunswick de 2005 à 2014 et sur les facteurs qui ont influencé les choix des médecins quant à l’emplacement de leur premier cabinet. Environ la moitié des répondants sont restés au Nouveau-Brunswick pour ouvrir leur premier cabinet. La plupart de ceux qui ont quitté le Nouveau-Brunswick pour ouvrir leur premier cabinet n’y sont pas revenus, alors que la plupart de ceux qui y sont restés exercent toujours leur profession au Nouveau-Brunswick. Le choix de l’emplacement du premier cabinet a été influencé par un ensemble de facteurs personnels et professionnels. Les raisons pour lesquelles les nouveaux médecins quittaient le Nouveau-Brunswick étaient surtout de nature personnelle.

Introduction

1 New Brunswick is a rural province that has a population of approximately 750,000, but is more than twice the size of the Netherlands (Statistics Canada, Annual Demographic Estimates).1 According to the New Brunswick Medical Society’s “Finding a Doctor” article, nearly 50,000 New Brunswick residents currently do not have access to a personal family physician, and the province has twenty-nine vacancies in family medicine.2 As of 2015, Statistics Canada estimates that 19.0% of New Brunswick residents are over the age of sixty-five, higher than anywhere else in Canada (Annual Demographic Estimates). The literature indicates that adults over the age of sixty-five generally utilize health care to a greater extent than younger individuals, exacerbating difficulties regarding access to primary care.3 In addition, Statistics Canada reports that nearly half (47.5%) of the New Brunswick population lives in rural areas (“Population, Urban and Rural”). Rural medicine presents unique challenges, such as the increased burden of travel in a province with poor public transportation;4 professional challenges for physicians, such as lack of resources (Miedema et al. 1141); and clinical challenges related to the high turnover of family physicians.5 This can be an expensive problem for rural communities that must continually invest in recruitment and retention with limited long-term success (Audas et al. 21–24). Similarly, although financial incentives are effective in the short term, they are less effective in terms of long-term retention (Sempowski 82–88).

2 Access to primary care is a critical component of the Canadian health care system, as patient access to specialist care is facilitated through the family physician referral system. Primary care in Canada is the responsibility of the individual provincial governments, resulting in different health care models between the provinces.6 The lack of timely access to primary care can lead to a cascade of problems and culminate in long wait times for health care.7 It is therefore prudent to consider factors that might influence physicians’ choice of practice locations and what this choice means for aging and rural populations.

3 Family physicians report choosing family medicine because of family, lifestyle, and professional reasons (Gill et al. 649–57). Several medical schools have created programs to emphasize the importance of family medicine and to recruit medical students from rural areas, with the expectation that they will be more likely to practice in rural areas. Dalhousie Medical New Brunswick (DMNB), an expansion of Dalhousie Medical School associated with the University of New Brunswick, has been training medical students and residents from New Brunswick since 2010 (Dalhousie University, “About Dalhousie Medicine New Brunswick”). Programs such as DMNB have been somewhat successful in Canada and the United States.8 For instance, a study examining the retention of francophone doctors in New Brunswick demonstrated that family physicians with a rural background are more likely to set up practice in a rural area as compared to their urban colleagues (Beauchamp 44–48). However, this study also found that setting up a rural practice was not predictive of family doctors remaining in rural areas. In a more recent study, Giberson et al. polled medical students to determine their willingness to practice in New Brunswick (25–31). Their results showed that being female, living in New Brunswick prior to medical school, attending one of the satellite medical schools (Université de Sherbrooke), completing preceptorship in New Brunswick, and having a desire to practice family medicine predicted willingness to stay in the province. Although findings such as these underscore the need for homegrown talent, other factors may play a role as to where physicians ultimately settle down.

4 Medical students often choose family medicine residency programs that suit their family and lifestyle preferences (Lee et al. 113–21; Lu et al.). After two years of residency, many prefer to stay flexible before settling into their career and establishing a practice in a permanent location (Beaulieu et al. 14–20), choosing to do locums to gain experience before establishing their own practice (Lu et al.). In other cases, residents take a liking to the location of their residency program and establish their first practice in the community.9 According to the Canadian Resident Matching Services (CaRMS), in 2015 more Canadian medical graduates applied to family medicine residency programs as their first choice (38.5%) than have in the past twenty-two years. Each year the Dalhousie family medicine residency program (Anglophone) trains approximately twenty family physicians at Dalhousie’s three New Brunswick residency sites, with the hope and expectation that many will remain in the province to establish a permanent practice. Retaining these physicians is crucial, as research shows that retention is more effective than recruitment (see Chauban et al. 101–7). Thus, knowledge of what specifically influences family physician retention in New Brunswick is vital to effective recruitment and retention efforts. For instance, Wasko et al.’s study on family physicians in Saskatchewan found that retention was more likely when physicians and their spouses and families were happy and felt integrated into the community, and when physicians felt appreciated by their patients and had a desirable scope of practice (93–98).

5 The primary goal of this study is to explore the retention of a ten-year cohort of Dalhousie University family medicine residents in New Brunswick and the reasons behind their decisions as to where to establish their first practice. In particular, our study investigates why some family physicians who completed their residency in New Brunswick remained in the province and why some decided to leave. Finally, our study examines whether the location of their residency training had an influence on their choice. This study was guided by three research questions: (1) What factors influence physicians’ choice of first practice location? (2) What factors specifically influence physicians who decide to leave New Brunswick to establish their first practice? (3) Does the location of the residency site attended relate to physicians’ decisions to stay in or leave New Brunswick to establish their first practice? The study thus expands on Giberson et al., which assessed willingness of medical school students who lived in New Brunswick before attending medical school to remain in New Brunswick after graduating (25–31). The current study uses a larger number of factors over a longer period of time, recruiting any physicians who completed their residency in New Brunswick regardless of where they lived prior to attending medical school, and is thus more comprehensive.

Methods

Participants

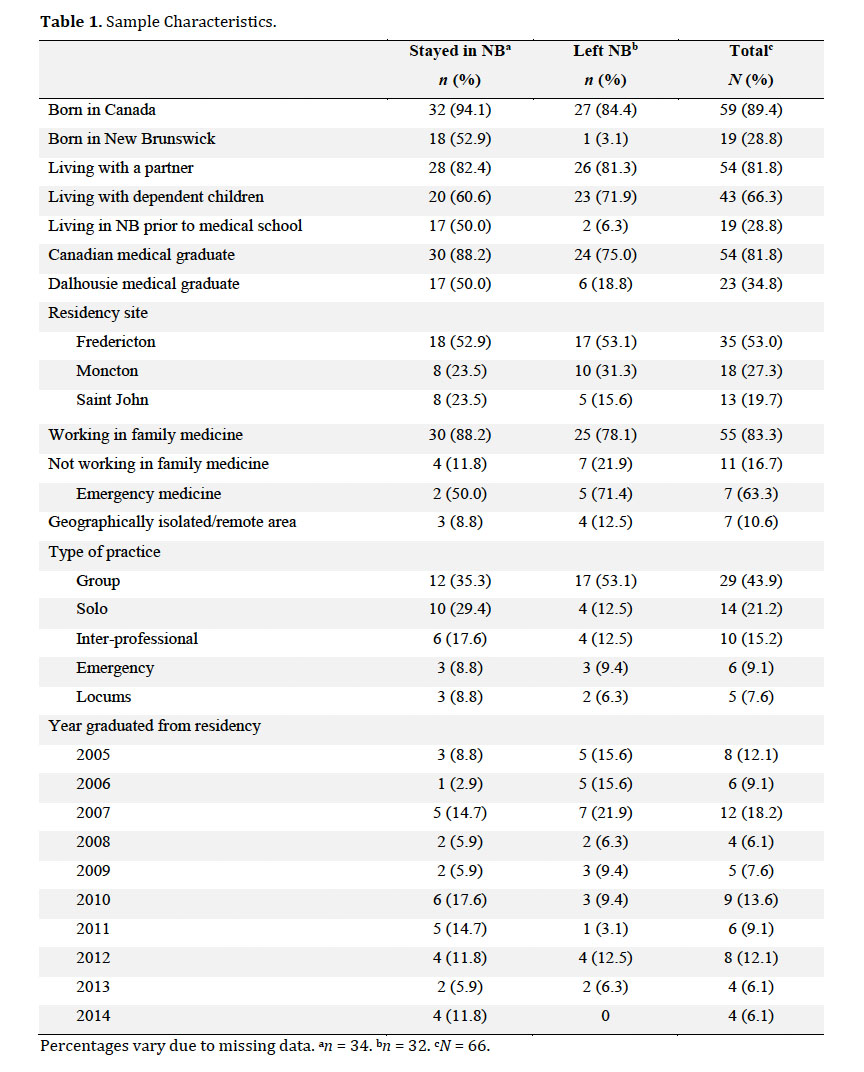

6 Graduates of the Dalhousie family medicine program who completed their residency at a New Brunswick site between 2005 and 2014 participated in this study. The final sample consisted of sixty-six physicians (43 women and 23 men), ranging in age from twenty-nine to forty-nine years (M = 36.59, SD = 4.34). Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Display large image of Table 1Percentages vary due to missing data. an = 34. bn = 32. cN = 66.

Display large image of Table 1Percentages vary due to missing data. an = 34. bn = 32. cN = 66.

Recruitment

7 Physicians were invited to participate by way of a letter mailed to their primary practice location. Mailing addresses of physicians’ practices are publicly available and were acquired through the websites of the colleges of physicians and surgeons in each province. The invitation letter contained study information explaining that the researchers were interested in the factors that determined the location of their first practice, and provided the URL to the online survey. The letter also contained the researchers’ contact details, explained the rights of participants, and informed the recipients that completion of the survey was considered consent to participate in the study.

Materials and Procedure

8 Physicians responding to the recruitment letter were required to type the link provided into their Internet browser to access the online survey. Upon following the link, participants were presented with an anonymous survey requesting demographic details, information about their primary practice location, and what factors were important to them when deciding where to establish their first practice after completing their residency. Information about these factors was collected using both populated checklists and broad, open-ended questions that allowed detailed responses. The survey was administered through Opinio, Dalhousie University’s online survey tool. One hundred and eighty-seven letters were mailed, eight of which were sent back marked “return to sender,” leaving a total of 179 letters presumed to be successfully delivered. Seventy-seven surveys were started (43.0 per cent response rate), but nine surveys were either incomplete or missing too many responses, and were excluded from the analyses. Also excluded were two participants who indicated they were military physicians and therefore had no choice regarding practice locations, leaving a total of sixty-six completed surveys. Respondents took an average of ten minutes to complete the survey. No compensation was offered.

Analytical Strategy and Ethics Approval

9 This is an exploratory study examining retention of family medicine residents in New Brunswick. After the descriptive statistics of the sample were analyzed, the factors that influenced physicians’ choice of first practice location were investigated. Then the factors that specifically influenced physicians’ decisions to leave the area were examined. Finally, a chi square test of independence was conducted to compare the residency site attended with physicians’ first practice location. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 21. Approval for this study was obtained from the Horizon Health Network Research Ethics Board (#2015-2145).

Results

Factors Influencing First Practice Location

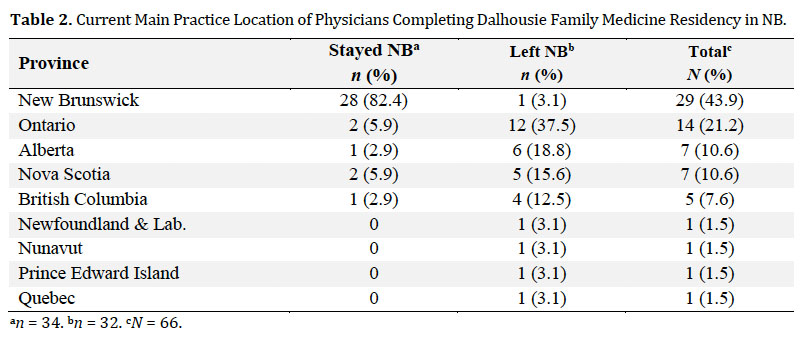

10 When establishing their first practice, 48.5 per cent of participants left the province, and 51.5 per cent remained in the same city or surrounding area where they completed their residency. Most physicians who established their first practice outside of New Brunswick are currently still operating their main practice in another province (96.9 per cent), whereas most physicians who stayed are still practising in New Brunswick (82.4 per cent). A summary of participants’ current main practice locations is presented in Table 2.

Display large image of Table 2an = 34. bn = 32. cN = 66.

Display large image of Table 2an = 34. bn = 32. cN = 66.

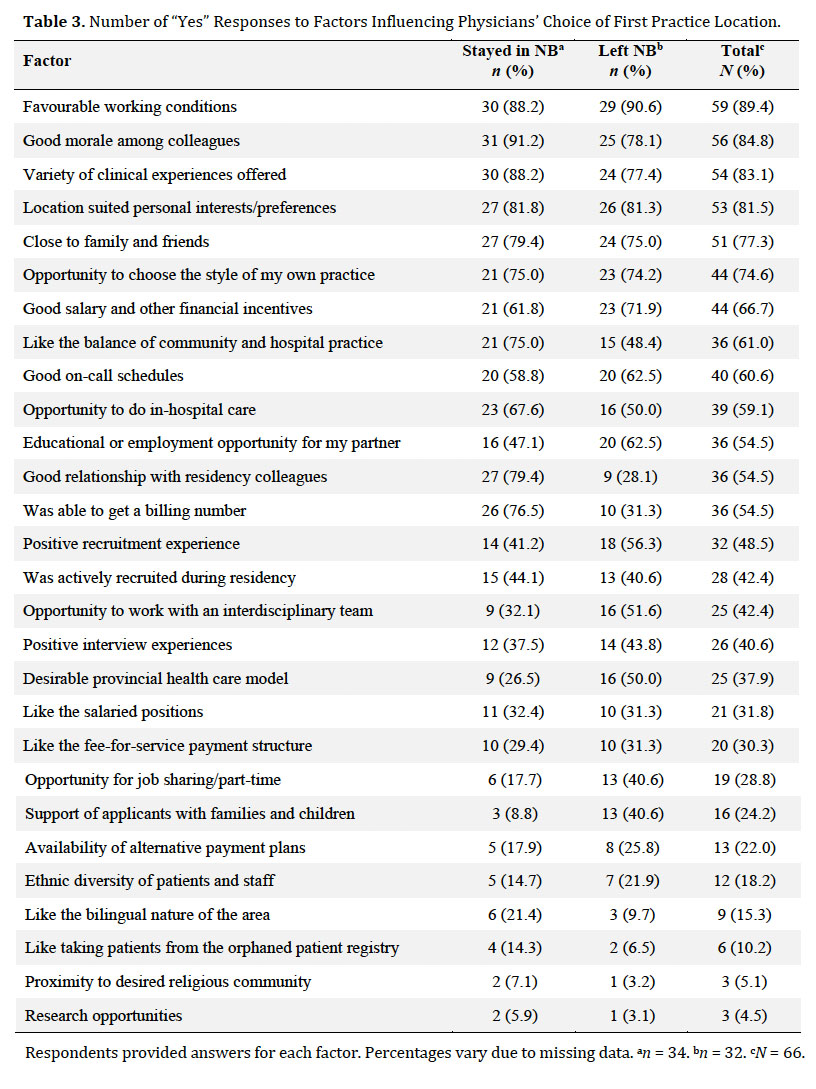

11 The majority of participants reported being influenced by a combination of personal and professional factors when deciding where to establish their first practice. A summary of all factors is presented in Table 3. The most frequently endorsed personal factors were a location that suited personal interests/preferences, was close to family and friends, and had educational or employment opportunity for their partner. These factors are reflected in comments from physicians who wanted to stay in or return to their hometown, or be close to their own or their partner’s family. As one participant stated in the comment section of the survey, “It was almost exclusively about proximity to family at that time” (FP25). Furthermore, several physicians stated their choice was heavily influenced by their partner’s employment opportunities. As another participant said, “Most influential was [the] lack of opportunities for [my] partner” (FP19).

Display large image of Table 3Respondents provided answers for each factor. Percentages vary due to missing data. an = 34. bn = 32. cN = 66.

Display large image of Table 3Respondents provided answers for each factor. Percentages vary due to missing data. an = 34. bn = 32. cN = 66.

12 The most frequently endorsed professional factors were favourable working conditions, good morale among colleagues, and the variety of clinical experiences offered. In particular, physicians who remained in New Brunswick reported feeling comfortable working in a familiar health care system, having established relationships with specialists, and working with colleagues they had trained with or under. One participant described it as follows: “I knew the system and was comfortable being able to talk with specialists when I needed help” (FP03).

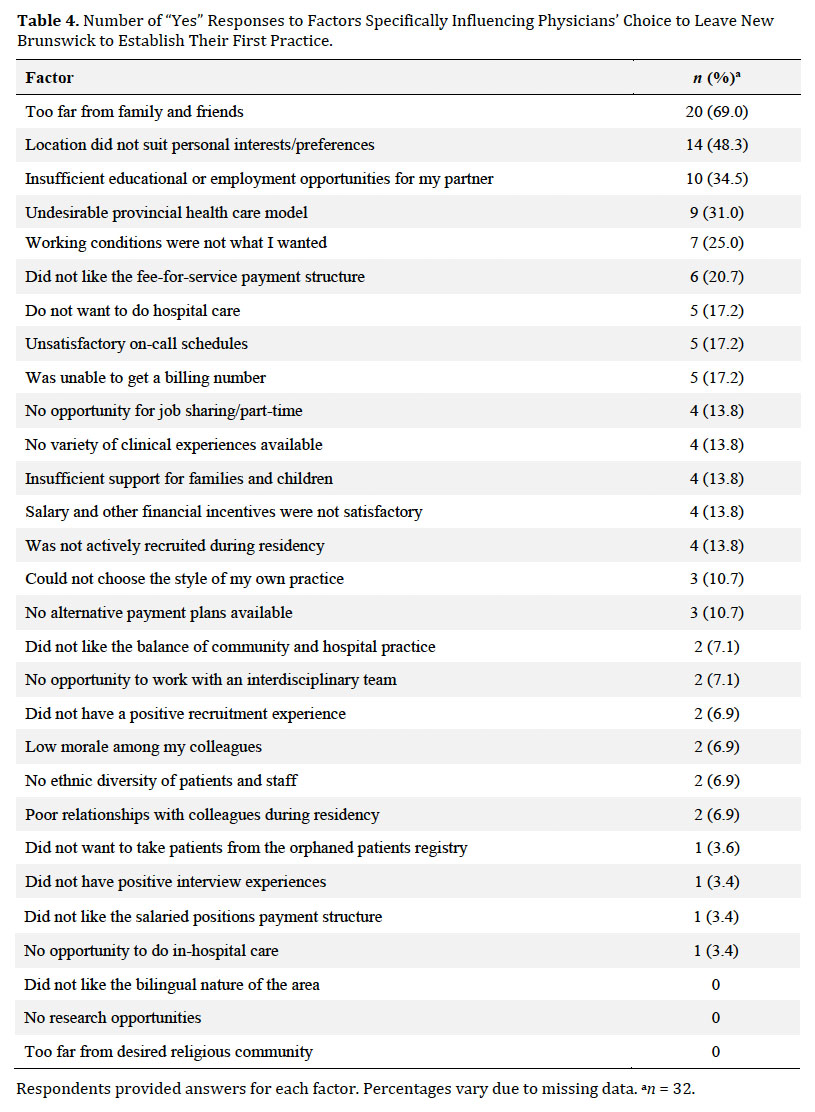

Factors Influencing Physicians Who Leave

13 When asked what factors specifically influenced physicians’ decisions to leave the province, personal reasons were prominent. Professional reasons were also cited, but not as frequently. A summary of all factors is presented in Table 4. The most frequently cited personal reasons were that the location was too far from family and friends, did not suit their personal interests/preferences, and had insufficient educational or employment opportunities for their partner. These factors are reflected in comments from physicians who reported having great experiences during residency and wanting to stay, but left in order to be close to family or because of their partner’s employment opportunities. One participant stated: “The main thing that took us where we ended up is the fact that my wife’s from there and her family is there, and we were both able to get a job. If it wasn’t for the fact her family was there, we would have likely chosen to remain in [location]” (FP46). Another participant said: “Doing residency in [location] was great experience, only thing that made us move from there was my husband’s job” (FP06).

Display large image of Table 4Respondents provided answers for each factor. Percentages vary due to missing data. an = 32.

Display large image of Table 4Respondents provided answers for each factor. Percentages vary due to missing data. an = 32.

14 Although physicians who left the province to establish their first practice cited personal reasons most frequently, they also identified professional factors that contributed to their decision. The most frequently cited professional factor was an undesirable provincial health care model, followed by working conditions that were not what they wanted, and not liking the fee-for-service payment structure. These factors are reflected in comments from physicians who reported being frustrated by a lack of support from recruitment staff and difficulties in obtaining billing numbers. As one participant wrote, “The health care system in New Brunswick did not seem sustainable and there was a perceived difficulty in getting a billing number” (FP67). Physicians who remained in the province also reported encountering barriers in the system. As one participant stated, “Support from [location] hospital medical staff in getting a billing number was crucial; otherwise effort to get billing number/difficult communications with Medicare [were] very frustrating and would have been a deterrent to staying in NB” (FP08).

Relationship between Residency Site and First Practice Location

15 A chi-squared test of independence revealed no significant relationship between residency site attended and physicians’ first practice location, χ2(2, N = 66) = 0.883, p = 0.643. Physicians who attended the three different residency sites were equally likely to leave or remain in the province when establishing their first practice.

Discussion

16 Bringing residency training to more rural provinces that have traditionally not had medical schools was developed to not only provide more training options for medical students, but also in the hope that some of these students would stay to practice after completing their training. This study has revealed that a combination of personal and professional factors influence family physicians when deciding where to establish their first practice. The findings broadly align with the extant literature that demonstrates personal preferences (e.g., proximity to family) and employment opportunities for a partner influence establishment of first practice.19 Similar to findings in the literature, opportunities for research was ranked low on the list of factors influencing first practice location.11

17 Based on the results of this survey, personal reasons are paramount when newly graduated family physicians leave the province; therefore recruitment strategies cannot be uncoupled from the family circumstances. Although there are other barriers to retention, family factors were identified as being important not only by those who left but also by those who remained. This suggests that recruiting more local residents may aid physician retention, which is consistent with the literature regarding the efficacy of recruitment programs for rural and underserved areas in Canada.12 An examination of the short- and long-term career choices of DMNB-trained physicians, the first cohort of whom graduated in 2014, could provide further insights. However, creating more training spaces is only one component of recruitment strategies. Physicians are a mobile group, owing to the highly marketable nature of their skills. Coupled with the Fraser Institute’s findings regarding an ongoing shortage of physicians in Canada (see Esmail, Canada’s Physician Supply), this means physicians can afford to choose positions that not only meet their professional needs, but that are also in locations that suit their personal preferences. This includes accommodating the current and future needs of their spouses and families. These findings are also consistent with previous studies (see Gill et al.; Lee et al.; Lu et al.) and may be indicative of regional characteristics that cannot specifically be countered with a recruitment strategy.

18 Professional reasons for leaving the province mainly involved system barriers, which also relate to regional characteristics. Physicians in Canada providing insured health care are paid through provincial health insurance plans, typically through a fee-for-service payment structure. In New Brunswick, this means family physicians must obtain a location-based billing number from the province in order to receive payment through Medicare (see the New Brunswick Medical Society’s “Fast Facts about Practicing in NB” for more information). Difficulties encountered when attempting to acquire a billing number were articulated by a number of physicians, both among those who stayed and those who left, highlighting an area for process improvement that may facilitate retention.

19 New Brunswick is a largely rural province, with half of the population living outside of urban areas (Statistics Canada “Population, Urban and Rural”). Previous work has demonstrated that family physicians may face unique challenges in rural areas (see Miedema et al.’s study detailing the problems of professional isolation and lack of resources [1141]). However, previous studies also found there can be many rewards in rural practice, such as getting to know patients. Wasko et al., for example, found that rural physicians enjoyed being able to practice the full scope of family medicine. New Brunswick has relatively high unemployment rates (9.9 per cent) compared to the national average (7.3 per cent), an aging population, and high rates of chronic disease and health risk factors.13 However, Statistics Canada’s “Police-Reported Crime Rate” demonstrates that New Brunswick also offers low crime rates, and the Canadian Real Estate Association’s “National Average Price Map” shows that New Brunswick enjoys lower real estate costs compared to the rest of Canada, as well as an abundance of provincial parks and green spaces for outdoor recreation, historical and natural landmarks, festivals, and cultural events.14 Recruitment strategies should focus on these benefits to quality of life and emphasize that physicians can enjoy the advantages of rural practice with some of the drawbacks being mitigated by the proximity of larger urban centres. Shifting policies may also influence the retention of physicians in the coming years: for instance, initiatives from the New Brunswick Medical Society for doctors to join family health teams, permitting more same-day appointments, and team-based care (Pruss).

Limitations of the Study

20 Although the response rate was good, this study focused on physicians who completed residency training in New Brunswick, thus limiting the generalizability of these results. In addition, the survey did not include questions about return-of-service or military obligations that would determine the location of first practices. The survey also did not capture specific information about physicians’ living situations prior to their post-secondary education, such as how long they lived in a particular province or whether they were living in a particular location out of preference or necessity (e.g., educational or employment opportunities, family obligations). Finally, physicians were not asked about the length of time between completing residency and the establishment of their first practice; thus the study failed to capture details regarding the timing of this choice.

Conclusion

21 Graduates of the Dalhousie family medicine residency program in New Brunswick choose the location of their first practice based on a variety of personal and professional reasons. When newly graduated physicians leave the province, it is primarily for personal reasons involving the needs of their spouses and families. Professional reasons for leaving the province largely relate to the provincial health care model. It should be noted that when newly graduated family physicians leave they are unlikely to return, whereas those who remain in the province tend to stay. Therefore, efforts to recruit and retain family physicians in New Brunswick that specifically address these factors may be beneficial to the long-term growth and retention of these physicians.