Refereed Articles

Falling Through the Cracks:

Barriers to Accessing Services for Children with Complex Health Conditions and their Families in New Brunswick

Access to a wide range of services is essential for children with complex health conditions and their families to ensure family-centred care that promotes positive outcomes. Despite this, these families often experience difficulties accessing the services they require. This study examined the services available and the barriers to accessing these services in New Brunswick, Canada. We conducted an environmental scan of services and semi-structured interviews with nineteen families and sixty-seven stakeholders from the health, social, and education sectors. We identified a wide range of services available to children with complex health conditions and their families. Barriers to accessing services were identified and organized into three categories: (1) service availability, (2) organizational, and (3) financial. These findings will inform policy and practice to improve services for these families.

L’accès à une vaste gamme de services est essentiel pour les enfants ayant conditions de santé complexes et leur famille afin d’assurer des soins axés sur les familles qui favorisent des résultats positifs. Toujours est-il que ces familles éprouvent souvent des difficultés à avoir accès aux services dont elles ont besoin. Dans le cadre de la présente étude, on a examiné les services offerts et les obstacles qui empêchent d’obtenir de tels services au Nouveau-Brunswick, au Canada. On a entrepris une analyse du milieu des services ainsi que des entretiens semi-structurés avec 10 familles et 67 intervenants des milieux de la santé, des services sociaux et de l’éducation. On a relevé une large gamme de services offerts aux enfants ayant conditions de santé complexes et leur famille. De plus, on a cerné les obstacles à l’accès des services et on les a répartis en trois catégories : les obstacles à la disponibilité des services, les obstacles organisationnels et les obstacles financiers. Ces conclusions façonneront les politiques et les pratiques afin d’améliorer les services pour de telles familles.

1 Growing attention is being placed on the challenges faced by families who have children with complex health conditions (CCHC) and on developing family-centred models of care to meet the needs of these families (Agrawal; Berry et al., “Inpatient” 170; Cohen et al., “Integrated Complex Care Coordination”; Dewan and Cohen; Elias et al.; Kuo et al., “A National” 1020). Timely access to a wide range of health, social, education, and community supports is essential to promote positive outcomes for CCHC, yet emerging evidence suggests that these children and their families often face difficulties in accessing the services they need (McManus et al. 222; MacCharles; McKee; New Brunswick Health Council, “Children and Youth in N.B.”; Rosen-Reynoso et al. 1041; Strickland et al., “Assessing Systems” 353; “Assessing and Ensuring” 228). This article reports the findings of a qualitative descriptive study that identified barriers to accessing health and related services in New Brunswick for CCHC and their families.

Background

2 Various terms have been used to describe the population of children living with “complex health conditions,” but the term commonly refers to children who have or are at increased risk for physical, mental, developmental, behavioural, or neurological conditions and are in need of health and other services beyond what is typically required for children (McPherson et al. 138; Cohen et al., “Children” 529; Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative 1). Complex health conditions can include attention deficit disorder, autism and other autism spectrum disorders, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, developmental delay, Down’s syndrome, heart conditions, intellectual disabilities, anxiety, depression, and traumatic brain injury. According to a recent survey by the New Brunswick government and the New Brunswick Health Council (NBHC), about 19 per cent of students in NB in grades 6 to 12 reported being diagnosed with a learning exceptionality or special education need in 2015/16 (“New Brunswick Student Wellness” 9). These conditions included attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention deficit disorder (ADD) (7 per cent); learning disability (5 per cent); mental health disability (2 percent); autism/Asperger syndrome (2 per cent); behaviour (2 per cent), and physical disability (1 percent). Moreover, about 17 per cent of younger children in kindergarten to grade 5 were reported to have been diagnosed with these types of conditions in 2013/14 (NBHC, “My Community” 33).

3 Although there is broad variation in the level of complexity, CCHC generally require medical and specialized care from a range of care providers across multiple settings (Bethell et al.; Cohen et al., “Patterns” e1463; “Integrated Complex Care”; McPherson et al. 138). Caregiving for CCHC can be overwhelming and challenging (McCann et al.; Nicoll 301). Daily family routines require thoughtful planning, organization, and coordination (McCann et al.; Putney et al.; Whiting, “Children”), and parents are increasingly spending significant amounts of time providing health care–related tasks at home (McCann et al. 26; Romley et al.). In addition, parents must plan appointments and provide technical care (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative; McCann; Nicoll; Whiting, “Children” 29); many families report having to quit paid work to care for their children (Kuo “A National Profile”). As such, these responsibilities have significant physical, emotional, and financial impacts on families (DeRigne 283; Lindly et al. 712; Romley et al.; Thomson et al.; Whiting, “Children”).

4 Timely access to services is essential to support these families, but unmet needs are common (Kuo “A National”; MacCharles). Studies in Canada and the U.S. have reported unmet needs in such areas as information and navigation (MacCharles); care coordination (Aboneh and Chui; Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute); rehabilitation therapy (Magnusson et al. 145; McManus et al. 222); genetic counselling (Smith et al. 544); dental health (Paschal et al. 62); medications (Aboneh and Chui); mental health (An 1); and transition planning from adolescent to adult services (Strickland et al., “Assessing Systems” 353). Moreover, parents often report having to “fight” for services to meet their child’s needs (Tétreault et al.; Whiting, “What It Means”). Whiting characterized this experience as a “battleground” for parents (“What It Means” 28).

5 Identifying unmet needs and barriers to accessing services is vital given the impacts for CCHC and their families, and the potential use of acute-care resources (Berry et al., “Optimizing”; Cohen et al., “Patterns” e1463). Improving access to health services is a major health policy goal in NB (Government of New Brunswick, “A Primary,” “Framework,” “New Brunswick Family Plan,” “Rebuilding”; Province of New Brunswick, “Listening”). Over the past decade, several NB reports have focused on the needs and gaps in services for children and youth (McKee; Government of NB, “Reducing”; Richard). In response, major initiatives have been implemented to improve service coordination and provide integrated service delivery and supports for at-risk children and youth with multiple or complex needs (NBHC, “Children and Youth,” “Children and Youth Rights”; Government of New Brunswick, “Framework,” “Reducing”). These include the integrated services delivery model, which offers services to children and youth who have multiple needs (Government of NB, “Framework”) and a mental health action plan to improve mental health services (Province of New Brunswick, “The Action Plan”).

6 Building on this work, our study focused on access issues for families with CCHC. Employing a qualitative approach to highlight the voices and concerns of families and stakeholders (i.e., service providers), our study offers a unique perspective on the difficulties that families of CCHC encounter and their perceived barriers to accessing services. The feedback of families and stakeholders can increase understanding of these barriers to inform program and policy development. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the existing services and identify the barriers to accessing these services across the health, social, and education sectors for CCHC and their families in NB. The two primary research questions were: (1) what is the scope of services available in NB for CCHC and their families? and (2) what are the barriers to accessing services across the health, education, and social services sectors in NB?

Methods

Study Design

7 We used a multi-method qualitative descriptive approach (Greenhalgh and Taylor; Vaismoradi et al.) to explore the research questions. We conducted an environmental scan to identify services available for CCHC (0–19 years of age) and their families. We then conducted semi-structured interviews with families as well as key personnel in health, social, and education to further identify the existing services and explore barriers to accessing these services.

Environmental Scan of Services

8 Environmental scans are often used by health care organizations, researchers, and decision makers to: (1) review current health programs and services; (2) assess challenges and gaps in service provision; and (3) inform decision-making for program planning and policy development (Rowel et al.; Scobba; Stacey et al.). A standardized data extraction tool was used to collect information on available services. We obtained the information through an extensive Internet search, and personal or telephone contact with key stakeholders. The types of data collected included a description of the program or service (e.g., location), program recipients (e.g., child or caregiver), eligibility criteria, referral information, cost, language(s) of service, contact information, and website address.

9 We synthesized data on programs and services using qualitative content analysis, which involves the interpretation of text data through a systematic classification process of coding, identifying patterns, and quantifying data (Dixon-Woods et al. 49; Hsieh and Shannon; Vaismoradi et al.). The scan took place between March 2015 and July 2016.

Interviews with Families and Stakeholders

10 We used purposeful and snowball sampling to recruit families and stakeholders. We selected the latter as potential participants due to their knowledge and experience in policy development and in providing services to CCHC and their families. In total, nineteen families and sixty-seven stakeholders were interviewed or participated in focus groups.

11 We used semi-structured interviews to examine participants’ experiences and explore barriers to accessing services (Gill et al.). We developed two interview guides: one for families, and another for stakeholders. The interviews were flexible in their format to facilitate two-way dialogue and elaboration in order to explore areas in more detail (Gill et al.). Interviews, which varied in length from forty to seventy-five minutes, were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by research assistants. All participants completed a consent form prior to participating in the interview.

12 We analyzed the interviews using Braun and Clarke’s inductive thematic analysis, which includes six phases: (1) familiarizing self with data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) providing the report. We initially coded the transcribed data using NVivo, placing units of text that referred to the same issue into meaningful categories or themes (Tuckett). The data was further coded using notes and keywords, and categories were refined through an iterative process that included in-person discussions among the coders and other team members. Quotes from the interviews are included in the paper to illustrate particular points. We identified quotes from CCHC and families as families and quotes from health, social, and education stakeholders as stakeholders. The protocol for the overall study is published elsewhere (Doucet et al.).

Setting

13 This study was part of a larger study that took place in NB and Prince Edward Island. This paper focuses on NB only. NB is an officially bilingual province and serves a population of about 751,000 (Statistics Canada, Population and Dwelling). Approximately 50 per cent of the population live in rural areas (Statistics Canada, Canada’s Rural Population). A full range of health services from primary health care (e.g., community health centres, public health, mental health services) to acute care are provided through two regional health authorities (Government of New Brunswick, “Horizon,” “Réseau”). NB also has major critical, trauma, and rehabilitation services such as the Perinatal Health Program and the Stan Cassidy Centre for Rehabilitation. There are no children’s hospitals in NB and some specialty services for children are offered out-of-province.

Ethics

14 The study was approved by the research ethics boards of Mount Allison University, the University of New Brunswick, the University of Prince Edward Island, Horizon Health Network, Réseau de santé Vitalité, and the Prince Edward Island Research Ethics Board.

Results

15 We identified a wide range of government and community-based services through the environmental scan and the stakeholder interviews. Barriers to accessing services were identified and organized into three categories: (1) service availability barriers, (2) organizational barriers, and (3) financial barriers.

Services for CCHC and Their Families

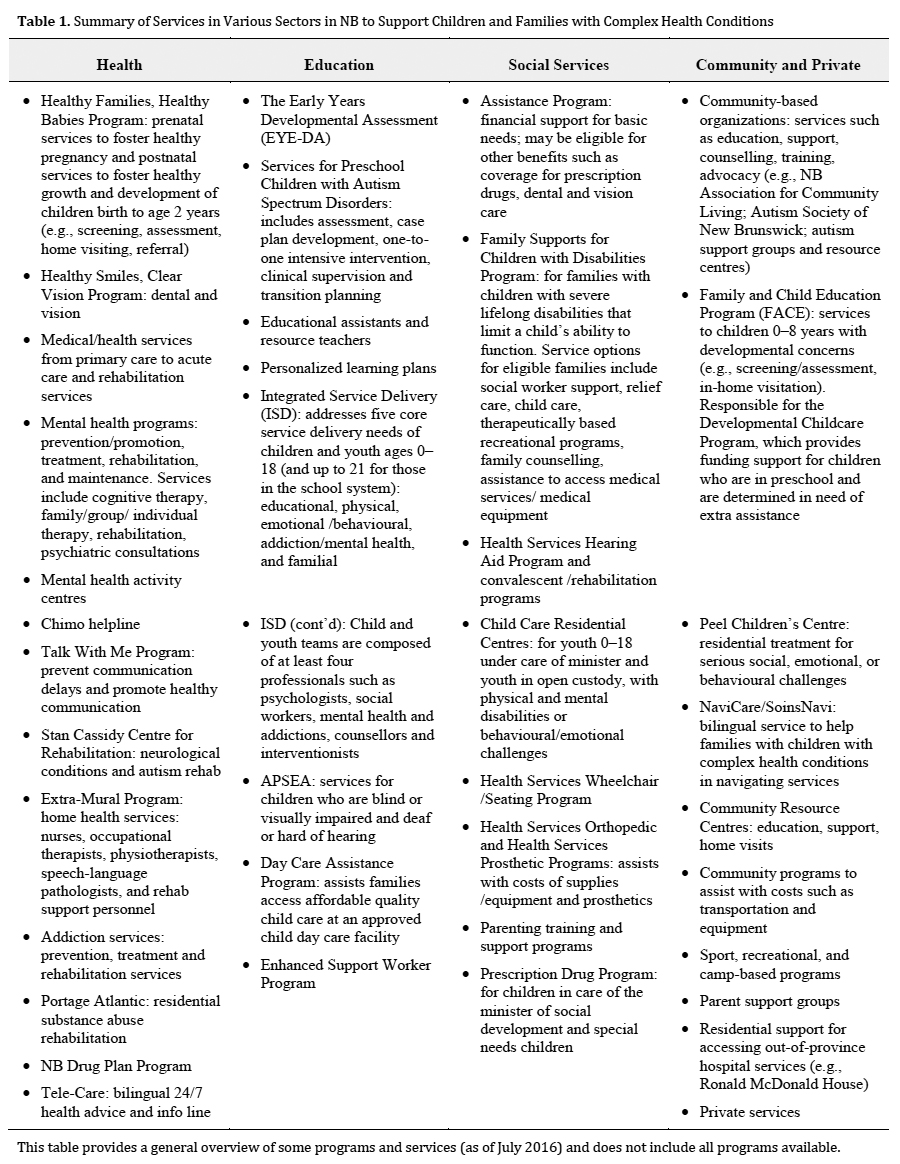

16 Services were provided across a range of settings including clinics, hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, schools, community, and in-home. The wide array of services included primary care; public health services (e.g., screening, assessment); rehabilitation; home health services; dental programs; vision and hearing services; mental health and addictions; residential treatment centres; wheelchair, orthopedic and prosthetic services; prescription drug programs; social assistance; financial support for day care assistance; support workers and families with children with disabilities; education services (e.g., preschool autism services, Integrated Service Delivery program, funding programs), community organizations (e.g., education, advocacy), community resource centres, and recreation programs. Table 1 outlines some of the services available for CCHC.

17 In addition to the in-province health services, health care specialists from other provinces travel to NB to provide consultation to CCCH in a range of specialty areas (e.g., rheumatology, genetics, cardiology). These services are appreciated by families and stakeholders, as noted by one family who stated: “And it may not mean that they automatically get into that clinic, it’s about timing. So say if they came twice a year, the families may choose to go to Halifax to be seen sooner. It’s a nice service actually.”

18 Some CCHC may need to travel to other provinces such as Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario for specialized services that are not offered within NB. The most frequently reported out-of-province services were located at the Isaac Walton Killam (IWK) Hospital in Halifax.

Barriers to Accessing Services

19 Barriers to accessing services were identified and organized into three categories: service availability barriers, organizational barriers, and financial barriers. Service availability barriers refer to gaps in services and the timely access to services. Organizational barriers represent organizational processes or policies that may hinder access to services (e.g., communication/collaboration across sectors, program eligibility requirements). Financial barriers are those that pose personal impediments to families to accessing services, as well as system resource barriers that can prevent or limit access to specific services.

Display large image of Table 1This table provides a general overview of some programs and services (as of July 2016) and does not include all programs available.

Display large image of Table 1This table provides a general overview of some programs and services (as of July 2016) and does not include all programs available.

Service Availability Barriers

Mental Health Service Gaps

20 According to stakeholders, service gaps occurred in pediatric mental health, including psychological and behavioural support services for both preschool and school-age children, particularly the latter. Several stakeholders reported limited access to these services to respond to behavioural and other mental health issues (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicide) and to meet the needs of children with autism. Commenting on the gaps, one stakeholder stated: “Yes, mental health issues definitely. We’re really not meeting the needs of children with mental health issues. We have a lot of that around anxiety, suicide attempts. These are our biggest issues you know in emotional wellness.” Another stakeholder commented on the frustrations of families and care providers and how gaps in mental health services impact the work of other health care providers:

Several stakeholders reflected on the gap in services for school-age children as is described in the following quote:

Reflecting on the gaps in psychology services, one stakeholder commented:

Another stakeholder described a gap in services for children with autism: “And then certainly in my domain, complex kids with autism—we are missing a lot, a lot of things. We’re missing behavioural consultants and residential services and crisis beds.” Stakeholders reported that service gaps are resulting in some children being admitted to hospital for extended periods of time, as described here:

21 Long wait times were reported for mental health services as noted by one stakeholder: “Lots of students go to [community agencies] as opposed to mental health. Usually because with mental health there is a huge wait list and the student is not deemed to be complex….I don’t want to speak on behalf of mental health, but they do have a wait list.”

Other Service Gaps

22 Stakeholders reported gaps in other service areas such as rehabilitation services, including physiotherapy and speech-language services, especially for school-aged children. According to one stakeholder, “A lot of children need physical therapy or occupational therapy and mental health services are huge as well.” There were also gaps reported in services for fetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD). As noted by one stakeholder, “When we look at children that have neurological FASD, it’s very hard first of all to get a diagnosis of that, and it’s very hard to get services in place for those children as well.”

23 Stakeholders also reported gaps in education services for children with autism spectrum disorder and other complex conditions. One stakeholder reported that financial cutbacks have led to some children sharing teacher aids while others may not be getting the assistance they need.

There were gaps in home services as reported by one family who expressed difficulties accessing home health services and fighting for services they needed:

A stakeholder similarly described the experience of some families who are fighting for services they need:

Organizational Barriers

Care Coordination

24 Care coordination gaps included issues around awareness of services, communication and collaboration across services, and continuity of care. In terms of awareness, families and stakeholders expressed concern that families lacked information about programs and services. Families reported relying on health care providers, other families, and neighbours for this information. One family commented:

25 One stakeholder commented on the difficulties that some families may encounter when seeking out the information they need: “Picture a single mom with a couple of kids at home and one with complex needs. They may not have the time or ability to seek out resources they desperately need.” In addition, stakeholders reported that they themselves are not always abreast of all the available resources but often take on this time-consuming role of identifying services:

One stakeholder commented on the types of service information that are needed by health care providers to help them assist families, such as details on referral policies, wait times, and cost:

26 Another stakeholder commented on the challenges of identifying services located across the province: “So you know finding the right place to send people is a challenge, but generally we can do it. But that would be the other thing. It’s not a standard system across communities and it’s even more challenging with the French and English programs in New Brunswick.”

27 Regardless of the type of information, stakeholders expressed that programs and services are not always well promoted. One stakeholder suggested a central website that could make it easier for health care providers to identify services for families:

28 A common suggestion from stakeholders and families was the need for a coordinator or navigator to help families identify and access services. A “one-stop shopping from a clinical perspective” concept was suggested for convenience of families to enable them to meet with multiple providers during the same visit. One stakeholder commented:

29 Stakeholders indicated communication and collaboration within and across sectors (e.g., health and education) could be improved. One stakeholder commented, “I think categorically, it’s coordination, communication, navigation, financial, mental health support, whether it be for primary problems or surrounding the distress that goes into it. Um, transition planning.” Another stakeholder suggested that some services across sectors are fragmented, working in silos, which can hinder access to services:

30 Stakeholders also reported a lack of continuity of care particularly from the preschool to elementary school for children with autism spectrum disorder as described here: “And the same thing for autism, children that have been diagnosed with autism here in the province. There are services for when they’re under five, but when they become school age it’s very difficult to get specialized services for those children.”

Training

31 Respondents identified several areas where additional training could enhance services in both the health and education sectors. Suggestions included additional training for education assistants and teachers working with autistic children, as described by one stakeholder:

Another stakeholder commented:

One family commented about their experience and the training of health care providers:

32 More training for service providers and those who provide respite was also suggested. One stakeholder reflected: “Specialized training in nurses and people who, and you know, homecare workers and the people who would provide respite or chronic care for these patients.” Another stakeholder commented: “We have a whole lot of people who will do the assessments and diagnosis. Like there’s a big rehab team at the hospital and they roll out with these diagnoses and treatment plans but there’s very few people trained to do the actual hands-on treatment plan that needs to happen.”

Policy-Related Barriers

33 Families and stakeholders reported that eligibility requirements can be restrictive and can limit access to specific programs. For instance, eligibility may be based on age, income, or confirmation of a diagnosis. As one stakeholder described, services are available for children with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but without a diagnosis or with more than one diagnosis, children may not meet the criteria for funding:

34 Other policy-related barriers included organizational mandates that limit access to services. For example, stakeholders reported that access to mental health services is limited for children with intellectual disabilities because these services are outside stakeholders’ mandate:

35 Similarly, another stakeholder commented, “Like autism. If you have a diagnosis of autism you can’t go to the mental health clinic for services. It’s like the two things are completely separate.”

36 Another stakeholder reflected on the challenges of working across sectors when trying to resolve issues:

37 In terms of other policy-related barriers, one stakeholder commented that government drug coverage policies are not adequate to cover the range of medications that are required for CCHC.

Financial Barriers

Personal Cost

38 Families may have additional costs related to travel within and out-of-province for services that are not available locally or in NB. When talking about gaps in services, one stakeholder observed: “There is a big gap in support here in the education system. I think access is a big thing, because of how remote we are from the specialist care centre. That would be the other big thing.” Other families may incur costs related to private services. According to one stakeholder,

System Resources

39 Stakeholders reported that cutbacks, inadequate resources, and funding caps may restrict the number of families that can access certain programs and services. One stakeholder commented:

40 Referring to a program within the Department of Social Development, one stakeholder noted that some programs have funding caps that can limit access: “And sometimes the other thing is that there’s a bottleneck. Not all kids who should be in the program can be in the program because there’s a cap on the funding for that. But it’s a good program.”

Discussion

41 This study explored the scope of services available and the barriers to accessing services for CCHC and their families in NB. A broad range of health, social, education, community, and private services were available to provide care and support. Access to these services is crucial to promoting positive health outcomes for these children (Peters). Similar to the findings of other studies, health care providers are a major source of support for parents (Whiting, “Support”). Families reported appreciating this support and the services provided.

42 Despite the range of services available for CCHC, this study suggests that the level of services is not keeping pace with the needs of CCHC and their families. Specifically, there were several barriers identified that can cause difficulties or delays in accessing the much-needed services. These included gaps in service availability, organizational barriers (e.g., care coordination, training), as well as personal and system financial barriers.

43 Care coordination is a vital component of high quality, integrated care to improve health and system outcomes (Turchi et al., “Patient” e1452–3). Although several major provincial initiatives are underway that aim to improve coordination and integration of services (Government of New Brunswick, “A Primary,” “Framework,” “New Brunswick Family Plan”), this study suggests that there is room for improvement. Effective strategies are needed to ensure families are aware of important services and to help them navigate the myriad services across multiple sectors. Stakeholders suggested that a care coordinator, such as a patient navigator, would be beneficial to help families identify and access services, and coordinate care. Care coordinators are widely used in practice and considered pivotal to meeting the needs of children and families with complex chronic conditions (Hillis et al.). In the absence of a care coordinator, health care providers reported that they often take on this coordination role, which can be time consuming and could potentially increase wait times for other families. It could also be an inefficient use of resources resulting in increased health care costs (Antonelli et al. 209).

44 Research suggests that pediatric patient navigation models of care can address a number of needs around care coordination (Luke et al.). As an outcome of the Doucet et al. study, a bilingual navigation centre, NaviCare/SoinsNavi, was recently launched in NB for CCHC and their families. A patient navigator helps CCHC and their families navigate through health, social, and education services. Building on this initiative, and based on our findings, we recommend the development of an online searchable database for families and service providers to provide additional support in identifying services. As a component of care coordination, these tools have been shown to assist in identifying resources to promote continuity of care across sectors (Taylor et al.).

45 According to stakeholders, service fragmentation and a silo approach to care continue to remain challenges for the system. These challenges can cause difficulties or delays in accessing services. Although provincial initiatives such as the Integrated Service Delivery program are in place to reduce the silo approach to care, this study suggests that these are areas for continued development in order to improve service integration and strengthen communication and collaboration within and across sectors. Service fragmentation can lead to a loss of continuity of care (Montenegro et al.), and stakeholders in this study suggested that services were lacking continuity of care for CCHC. Continuity of care refers to high quality, coordinated health care management that reduces fragmentation, and ensures that care provided by multiple providers is coherent and connected, and meets the changing needs of families over time (American Academy of Family Physicians; American Pediatric Society 1; Reid et al.). Family-centred care is required to provide a seamless continuum of service that responds to the changing needs of these children and youth as they grow and develop.

46 Optimal use of technology can improve communication among health care providers by providing easy access to patient information at the point of care and facilitating sharing of information among providers across settings. The current initiative underway in NB to implement electronic medical records across the province will enhance communication and improve coordination in collaborative team-based settings (Government of New Brunswick, “Primary Care”).

47 The use of care plans can also enhance collaboration and sharing of information, while strengthening family-provider relationships (Adams et al.; Kou et al., “Recognition” e6; Lion et al.). Electronic care plans that are integrated into electronic health records have been shown to improve collaboration and information sharing, and are valued by parents as a tool that can facilitate timely and effective care (Kingsnorth et al., 57; Kuo et al., “Recognition”).

48 This study also suggested that better access to mental health services is needed for CCHC and families. Improving access to mental health services has been identified as a priority in New Brunswick (Government of New Brunswick, “New Brunswick Family Plan”), and there are major initiatives underway to improve access to these services. These include the implementation of the Integrated Service Delivery program and the Mental Health Action Plan, the establishment of a Network of Excellence and the Centre of Excellence for Complex Needs Youth, as well as increased investments in mental health services (Government of New Brunswick, “Listening,” “Framework”; Province of New Brunswick, “State of the Child,” “The Action Plan,” “Progress”).

49 Schools are a key environment to promote positive mental health and provide early identification and intervention to address mental health problems (School-Based Mental Health and Substance Abuse Consortium (SBMHC 1). NB’s ISD model is about enhancing coordination among departments, school districts, and health authorities using a team-based approach (e.g., psychologists, mental health, social workers, school counsellors) to improve support for CCHC with multiple emotional, behavioural, and mental health needs (Government of New Brunswick “Framework”).

50 Despite these promising initiatives, further work is needed to address the challenges identified in this study related to access to mental health services for behavioural and other mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, and addressing the needs of children and youth with autism. As found in this study, mental health issues remain significant challenges for youth with complex health conditions in NB. The most recent Student Wellness Survey reported that 33 per cent of students in grades 6–12 with a learning exceptionality or special needs reported low levels of mental fitness compared to 21 per cent of the general student population. In addition, about 25 per cent reported high levels of oppositional behaviour compared to 15 per cent of the general student population, and about 45 per cent of students with learning exceptionality or special needs reported symptoms of depression or anxiety compared to about 33 per cent of the general student population. (New Brunswick Health Council, “Student Wellness Survey” 11–12, 21).

51 Timely access to early intervention and treatment is crucial, as the progress of children with developmental and mental health conditions is significantly improved when diagnosis and treatment are not delayed (Gautier, Issenman, and Wilson). Without timely and appropriate care and support, some children may be at increased risk for falling through the cracks and being cared for in an expensive and non-suitable acute-care system. Compared to other provinces, New Brunswick utilizes more hospital-based care for youth mental health conditions (Province of New Brunswick, “State of the Child”). Young people ages 15–17 are being hospitalized more often than other youth their age in Canada, and only 50 per cent of children and youth ages 0–18 who are seeking care in the formal health system can get the mental health services they need within thirty days (New Brunswick Health Council, “Children and Youth” 14, 17).

52 These challenges are complex and cannot be addressed overnight. Appropriate resource allocation and adequate service provider staffing and capacity are essential to meet the growing demand for these services. The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) recommends that provinces allocate at least 9 per cent of health care resources to mental health services over the next ten years (Mental Health Commission of Canada, “Changing Directions” 126). The MHCC has just released a report on successful initiatives to address mental health needs that can result in cost savings while improving mental health outcomes (MHCC, “Strengthening” 6). These initiatives include community-based rapid response teams, increased access to psychotherapy, primary prevention and early intervention programs, and parenting programs.

53 Expanding the use of telemedicine in NB can also help improve access to mental health services for CCHC and their families. A recent review by Canadian researchers concluded that the use of technologies is increasing substantially and plays a significant role in providing access to much-needed mental health services and supports or children and youth (Boydell et al. 87). This is particularly true in rural and medically underserviced areas where telemedicine has been shown to be effective, and a potentially cost-effective approach for increasing access to services, including behavioural and mental health services for children with special health care needs (Hooshmand and Yao 18–23). Health care providers and families also express high satisfaction with these services (Hooshmand and Yao 22–3).

54 Our findings suggest that disparities to health care access exist due to policy, financial, and geographic barriers. CCHC and their families may be at higher risk for poorer outcomes if they cannot access the services they need. Reviewing existing policies and eligibility requirements, and increasing investments in these programs are necessary to better support all CCHC and their families, especially those living in rural and remote areas of a semi-rural province. Government and many community-based services are provided in certain locations across the province, making it more difficult for some families to access these services.

55 This study also highlighted the ongoing need for training for service providers in the health and education sectors to build skills and capacity for supporting children and families.

56 Innovative health policies and strategies as well as training and adequate resources are necessary to provide family-centred, high quality care that meets the long-term needs of these families. Not addressing these unmet needs during a critical time of child development may leave CCHC and their families at risk of falling through the cracks, which can put them at greater risk for poor health outcomes and additional stress.

Future Research

57 Drawing on the voices of families of CCHC and stakeholders, this paper presented their perspectives about the struggles families encounter in accessing the services they need to promote optimal health outcomes for their children. Previous reports have identified similar barriers, yet the challenges persist despite the best efforts of policy-makers. Future research could examine in further detail why these barriers persist.

58 To better serve CCHC and their families—namely, through the provision of high quality, family-centred care—one must understand service gaps and unmet needs. One area that merits future investigation is to examine current initiatives in place across Canada and abroad that assess and monitor service quality and outcomes for these children and families, including level of unmet needs, access to services over the long term, and family experience with services provided. This will help target areas for improvement and monitor progress in meeting the needs of CCHC and their families.

Strengths and Limitations

59 The strength and originality of this study was the qualitative approach that encouraged participants to share their concerns about the availability of services and the barriers to accessing services for CCHC and their families. Indeed, to identify areas of improvement, it is necessary that policy-makers hear the voices of both families and stakeholders involved in the care of CCHC.

60 Although the combination of an environmental scan with semi-structured interviews was a useful approach to identify existing programs and services, this study had limitations. First, programs and services are constantly evolving. Therefore, we may have missed some. Second, the scan in and of itself did not provide data on the utilization of these programs or awareness of each program by families of CCHC. Third, our findings are not generalizable to settings outside of NB. Nevertheless, this study provided a useful template for other jurisdictions as a starting point for initiating a repository of information to assist families and stakeholders in supporting CCHC.

Conclusions

61 Families of CCHC require a multitude of services across government and community to meet their medical, developmental, physical, mental, psychosocial, and spiritual needs. Although a range of programs and services are available in NB, and major positive initiatives are underway to improve the integration of service delivery and access to services, considerable barriers exist that hinder access to needed services, and there is room for further development. Gaps in service availability, organizational barriers, and financial barriers affect service quality and access to these services. The results of this study can inform current and future policy and program improvement and development. Supportive policies, increased integration and coordination, training, and adequate program and human resources are needed to meet the growing needs of these families and to provide optimal, proactive care. Integrated approaches are vital not only to improve CCHC/family experiences, quality of life, and health outcomes, but also to reduce health care costs.