Refereed Articles

Diagnosing Collective Memory Loss:

Integrating Historical Awareness into New Brunswick’s Health Care Policy Debate

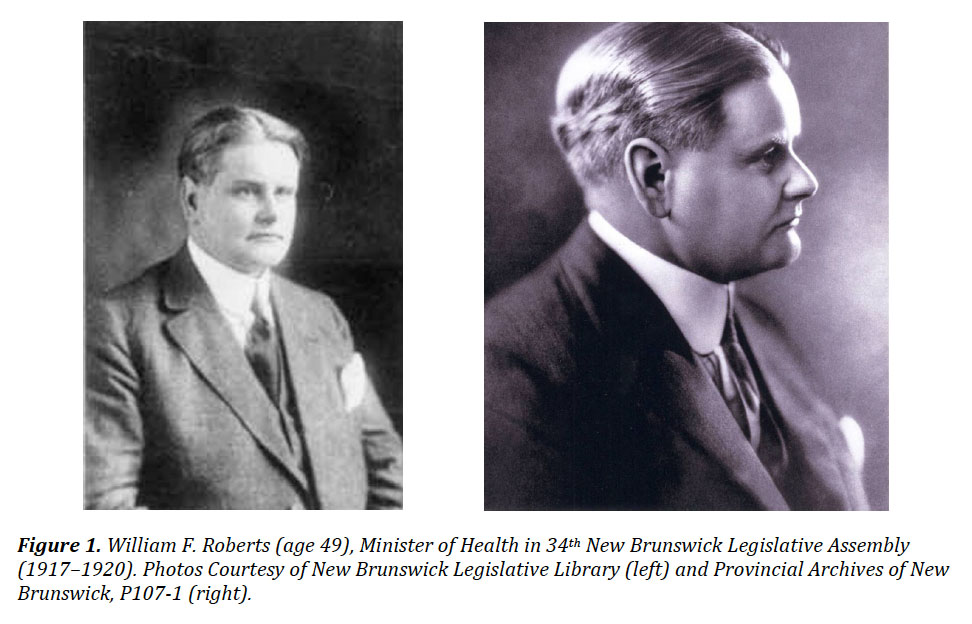

This paper is a case study of how public awareness of New Brunswick physician, politician, and public health reformer, William F. Roberts (1869–1938), has faded in and out of historical consciousness. Reflecting the historical mood of the times, his accomplishments have been variously lauded as a bold landmark in the province’s push towards progress and innovation, lamented as a symbol of institutional paternalism, or forgotten altogether. This case shows that historical narratives (or their absence altogether) reveal more about the present in which they are constructed than about the past they describe and is presented as an argument for greater historical contextualization of current health care policy debates.

Le présent article se veut une étude de cas sur la façon dont la sensibilisation du public à l’égard de William F. Roberts (1869–1938), médecin, politicien et réformateur de la santé publique du Nouveau-Brunswick, s’est estompée de la conscience historique. Reflétant les sentiments historiques de l’époque, la prise de conscience de ses réalisations a été applaudie de différentes façons comme une réalisation marquante dans les efforts de la province vers le progrès et l’innovation, déplorée comme un symbole de paternalisme institutionnel ou complètement oubliée. Cette affaire montre que les récits historiques (ou leur absence totale) en disent plus sur le présent dans lesquels ils ont lieu que le passé qu’ils décrivent et sont présentés comme un argument pour une plus grande contextualisation historique des débats sur la politique relative aux soins de santé actuels.

1 People in New Brunswick, like all Canadians, have grown accustomed to universal and comprehensive health care, but the health care system in New Brunswick faces a unique array of challenges to its sustainability. Statistics about overcrowded emergency rooms, long wait times for surgeries, physician shortages, and an aging demographic fuel debates about how to sustain the province’s health care system in the long term. Policy-makers and politicians call on economists, political scientists, sociologists, and health care providers, administrators, and consumers for input on how to resolve the system’s contentious and complex issues. Wholly absent from these discussions, however, are historians. And historians are not the only ones lamenting this absence. A prominent Canadian scholar of health policy recently observed that the debate over the future of health care systems in Canada “has generated more heat than light,…because the arguments and positions are so often poorly informed by history.”1 Other scholars, including prominent Canadian and American historians of medicine and of public health, echo this complaint and argue that deeper and clearer analysis of contemporary challenges facing health care provision will emerge by integrating an historical awareness of shifts in attitudes, institutions, and approaches to health and health care over time. Missing the opportunity for such integration and facing collective memory loss diminishes the likelihood for creative resolution of contemporary problems.2

2 In areas other than health care, the past seems to matter a great deal to Canadians, and this is especially the case in 2017, as many celebrate 150 years of the “peace, order and good government” of the country. The federal government has allocated half a billion dollars to celebrate this anniversary by funding everything from refurbishment of community arenas and museums to online projects like the one to “rediscover Canadian history” or another that asks Canadians to describe what the country means to them.3

3 Premier Brian Gallant announced New Brunswick’s own plans for the sesquicentennial celebrations when he unveiled the province’s slogan: “Celebrate Where It All Began!” The premier noted that “New Brunswickers are proud of who they are and where they came from,” before proclaiming that “we are going to tell the world about it” and announcing the injection of ten million dollars to promote sports, cultural, and tourist events as well as “heritage activities” to stimulate economic activity, celebrate what it means to be “NB Proud,” and attract tourists.4

4 The slogan, making the claim that the idea of Canadian confederation was first suggested in 1861 by New Brunswick’s Lieutenant-Governor, Arthur Hamilton-Gordon, is a prime example of how historical individuals or events are often groomed as emblems of precedence or exceptionalism, on the bet that such a priority claim for uniqueness will translate into business and tourist dollars. Such construction of a collective historical narrative for use as a deft political tool of government is nothing new.5 In the 1950s and 1960s, government officials in Nova Scotia constructed a one-dimensional and highly romanticized version of the province’s complex history in an explicit campaign to boost the tourism industry.6 And this year’s national celebrations of Canadian nationhood echo extravagant celebrations held at the country’s 50- and 100-year milestones that were also choreographed to exude an idealized vision of national identity while also drawing tourists.7 Scholarly studies of historical consciousness reveal the linkages between the memorialization and commemoration of the past and the social, political, and economic landscapes of the present.8 These links are particularly apparent when an individual person from the past is spotlighted, identified as an historical hero and glorified with monuments and statues, or as a named building, to tacitly broadcast a social and political identity or theme both relevant to the present and optimistically pointing a path to the future.9 But unlike the stone monuments and statues that keep the heroes frozen in time, the narratives attached to these heroes do not remain static but shift, transform, or fall out of favour, fading out of public consciousness.

5 Heritage sites across New Brunswick that memorialize people, places, and events reveal these inevitable shifts. The sites commemorate diverse ethnic, cultural, and linguistic traditions—Aboriginal, British Empire Loyalist, Acadian—and celebrate, too, the province’s distinctive traditions of lumber, fishing, and mining. Indeed, the province’s past is crowded with people, symbols, and events ripe for mining by tourist managers and government officials to serve the needs of the present, whether to fuel tourism campaigns or to inspire or reignite pride of identity. Nonetheless, the bottom line reflects today’s consumer-oriented economy, and any choice of historical figure for public consumption has to draw consumer dollars.

6 Certainly, historic moments from the province’s rich experience in public health care reform do not fit the bill. Even though health care is as iconic a symbol of the Canadian identity as hockey, moose, or maple syrup, awareness of its historical development in New Brunswick is obscure. Indeed, the province’s distinctive role in initiating early twentieth-century public health reforms long before Medicare’s “birth” in 1960s’ Saskatchewan is so lost from public memory that the upcoming hundredth anniversary of the establishment in New Brunswick, in October 1918, of Canada’s first stand-alone government department of health will undoubtedly warrant little attention. And yet, health care is often mythologized in narratives crafted to define the country’s distinctive character, held up as an emblem of liberal democracy blanketing the entire nation. But histories of the emergence of public health reform in Canada rarely, if ever, mention New Brunswick, even though its innovative Department of Health, established in 1918, was the first full ministry of health in Canada. The collective memory loss of early twentieth-century New Brunswick achievements in public health reform from national, and especially from provincial narratives, reveals several things, not only about histories of Canadian public health history but also about historical consciousness and the nuances of public memory. The absence of New Brunswick in national narratives of public health reveals the deep persistence of negative regional stereotyping of New Brunswick as underdeveloped, less modern, and, therefore, incapable of innovative reform. Furthermore, the absence of New Brunswick from regional narratives of public health shows that this pejorative typecasting of New Brunswick is so pervasive as to have been absorbed and recapitulated in the stereotyped region itself, perhaps indicative of the region’s meta-narrative of inferiority.10

7 But such has not always been the case, for at times in the twentieth-century, public health reform in New Brunswick was loudly applauded and commemorated as a hopeful promise of modernity and progress. Dr. William F. Roberts (1869–1938), the man who had spearheaded the reforms and who was the province’s first minister of health, was lionized as a hero worthy of world-class praise. But by mid-century, Roberts and his public health initiatives had slowly faded from public memory in New Brunswick, and today, if remembered at all, Roberts’s name is negatively associated with the shame and notoriety that followed allegations that child residents of the residential school that bore his name had been abused.

8 This paper explores the social construction of William F. Roberts as a provincial hero, and the shifting status of Roberts in public memory, as he was variously lauded, lamented, and forgotten altogether over the course of the twentieth century. Drawing on the interpretive techniques pioneered in the cultural study of historical consciousness, this paper examines the shifting historical awareness of Roberts and his role in public health reform as a case study in how historical narratives (or their absence altogether) reveal more about the present in which they are constructed than about the past they describe. Mapping, or diagnosing, collective memories and memory losses of past public health reformers like W.F. Roberts—and of past policies—offers insight into how public attitudes towards and reception of new or revised health care policies ebb and flow along with powerful political, ideological, and economic forces.

The Crafting of William F. Roberts as Public Health Hero

9 The Public Health Act 1918, passed into law by the New Brunswick legislature on 26 April 1918, was labelled “Dr. Roberts’s health bill” by everyone from newspaper reporters to politicians from the time Roberts first tabled the bill on the floor of the legislature several months earlier.11 This was not the first time Roberts’s name had been synonymous with public health reform. Before seeking political office in the 1917 provincial election and proposing the innovative Public Health Act, Roberts had been a widely known and popular physician in Saint John, having established his medical practice there after graduating from the prestigious Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City in 1884. He became involved in all manner of health-related projects in the community, from instructing the local ambulance association to campaigning for public parks for youth and supporting voting rights for women.12 Once appointed coroner of Saint John in 1902, he became even more actively involved in pushing for municipal reform of regulations and bylaws related to slaughterhouses, milk supplies, sewage disposal, disease epidemics, and health inspections of schools. Extending his agitation for the improvement of public health conditions from his home city to the entire province, Roberts’s run for the Liberals in the 1917 election promised “improvements in matters affecting the health of the people” by establishing a department of health if the Liberals could beat the incumbent Conservatives.13

10 When Roberts won his riding in a narrow sixty-vote victory and the Liberals won a slim majority, the battle for the health department had just begun. Debate in the legislature of “the Roberts bill” was raucous, and opposition to the fifty-eight sections of the bill was widespread, even among members of Roberts’s own party.14 Much of the opposition railed against the autocratic powers the legislation would grant to the new minister of health. Roberts felt that “the machine guns of the opposition had been directed against” his health legislation and aimed directly at him.15 Attacking the proposed bill meant attacking Roberts. One Conservative MLA, J.B.M. Baxter, suggested that the whole purpose of the bill was “to provide a portfolio” for Roberts, echoing an editorial in the Saint John Standard that had suggested that the department would be created “to satisfy the vanity and personal ambition of a gentleman at present in the forecastle of the Foster administration.”16 Another editorial argued that a vote for Roberts’s bill would confer “upon the honorable minister a power greater than that held by a Tsar of Russia,” and that passing the health act would be “the most unhealthy thing the government could do.”17 The proposed Department of Health was deemed “an absolutely unnecessary, expensive and cumbersome administration of the problems of public health,” and critics continued their scathing character assassination of Roberts, calling him self-interested and full of “complacent pomposity.”18 Even when newspaper headlines proclaimed “Roberts health bill is passed,” on 26 April 1918, it was still described as a “monstrosity of legislation, particularly drastic in some of its provisions and foolish in most of them.”19 After the new Department of Health was formally proclaimed into law by the province’s lieutenant-governor on 3 October 1918, Roberts recounted that the process of getting to that point had been “one of the hardest fought battles surrounding any act during the last half-century.”20 The hard-fought battle over the health act and the rabid animosity that had been hurled at Roberts himself held out little promise that both would later become staples of historical memory and commemoration in the province.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

11 Little did he know that the battle had just begun, this time not with government opposition but with the deadly influenza bacteria that was slowly working its way into New Brunswick that fall of 1918. While there had been reports of the epidemic raging in Quebec and the Boston area, New Brunswick newspapers reported cheerfully that “the epidemic will probably pass away,” and that even on the off chance it did strike close to home, all one needed to combat it was a positive attitude and plenty of fresh air and sunshine.21 Within days, however, cases of influenza were rampant. Fredericton, a small town of 7,500, was paralyzed, with over one thousand reported cases. Casket makers in Grand Falls could not meet demand. The lone doctor in St. Joseph, near Dorchester, noted that over fifteen hundred sick people needed medical help. By the middle of October 1918, several thousands of people lay sick and dying in towns, villages, and rural farmhouses throughout New Brunswick. Roberts wasted no time and used his sweeping powers to issue a province-wide proclamation, ordering that “all schools, theatres and churches in New Brunswick be closed on and after Friday 11 October.”22 Businesses were allowed to remain open and streetcars in Saint John were kept running, but people were implored to prevent overcrowding. Roberts and Dr. George Melvin, the Chief Medical Officer of Health and the only other official in the nascent Department of Health, coordinated volunteer and other government officials in their efforts to manage the epidemic crisis.

12 Criticism of the Department of Health did not abate with the outbreak. Through October and November 1918, while the epidemic was at its height, newspaper editorials accused the Department of Health of being unprepared for influenza, even though Roberts had warned of its arrival. The department was attacked for being unresponsive to pleas for assistance, and for inefficiency, ineptitude, and inaccurate reporting of the true number of cases. Roberts himself was accused of being “the wrong man at the helm” and “false to the trust he had actively sought.”23 Hitting its peak in November 1918, the epidemic slowly faded away by the end of January 1919. Also dissipated was the energy that had buoyed widespread criticism of the new Department of Health. The sentiment that the public’s health had no place in politics changed dramatically after the flu epidemic, and praise for the department flooded in. Minto’s local doctor thought that “the limiting of the epidemic in this locality largely to the mining camps, was in great measure due to the action of the Department of Health at the onset of the epidemic.”24 Another letter writer felt that the health department’s role in mitigating the epidemic’s impact was “just as much needed as helping win the war.”25 Much of the praise was directed towards Roberts himself. A national nursing association congratulated Roberts “for the able manner in which the recent influenza epidemic was handled,” and the editor of the Saint John Telegraph wrote shortly after the outbreak that “the disease has proved the absolute necessity of health regulations such as Honourable Dr. Roberts succeeded in engineering through the legislature last session.”26 One member of the village council of Upper Gagetown predicted that after the epidemic “there will be no one in this place who will be opposed to the Health Bill.”27 A hero, and an incipient historical myth, had been unexpectedly born.

13 After facing serious criticism, the Department of Health had solidified its own existence by providing the powers that allowed Roberts to deal effectively with the influenza epidemic. The welcome relief that came with the realization that people had survived four war-weary years and the terrible epidemic, with better times ahead, seemed to emanate from the new Department of Health and William F. Roberts, its flag-bearer. Roberts became the personification of the mood of confident optimism that had sustained the early twentieth-century progressive reform movement. Since the turn of the century, with urban centres, population, and industry on the rise, the regional magazine aptly named The Busy East commented on the prosperity and optimism transforming the province with sweeping reforms in education, worker and voting rights, and urban planning. But the optimism and promise of economic growth and expanding opportunities, so tangible in the opening decades of the twentieth century, were unsustainable. The traditional fishing, lumber, and mining industries stumbled, and the new industrial economies could not compete with expanding industries in central Canada. With no help on the horizon from the federal government and a sputtering economy, the hopefulness of the so-called reform movement was a mere “stillborn triumph.”28

14 If, however, the wider reform movement fell short of its idealistic goals, the presumed linkages connecting science, medicine, and public health to a confident trust in progress remained strong. Roberts made sure of that. Using his connections with American public health reformers, Roberts successfully lobbied for a $54,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to pay for six full-time health inspectors to monitor the health of the province’s school-aged children. And within two years of the Department of Health’s creation in 1918, district medical health officers, sanitary inspectors, and public health nurses opened free government-financed clinics to control tuberculosis and venereal diseases; they also offered education classes on nutrition and infant care, inspected the physical, dental, and mental health of school children, and administered mandatory smallpox vaccinations. Infant mortality rates swung dramatically from the highest to among the lowest in the country. As well, a central laboratory, set up in Saint John’s General Hospital, was overseen by American-trained Harry Abramson, hired by Roberts for his expertise in bacteriology, chemistry, and pathology. Following Roberts’s dictum that bacteriology was the central core of public health reform, this laboratory complemented public health services by examining specimens for tuberculosis, diphtheria, and typhoid fever, and monitoring for contaminants in milk and water supplies.29

15 Roberts’s singular determination to apply the relatively new science of bacteriology to the management of public health reflected the core of his medical education at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City, which emphasized bacteriology and laboratory training for its students. The college handbook crowed that bacteriological analysis was triggering “a revolution” in exposing the microscopic causes of disease, with results “to be of incalculable value to humanity.”30 Buoyed in part by this belief in the optimistic promise of science and medicine, Roberts was re-elected to the provincial legislature in 1920, along with the Liberal party. But the deep discord that had animated disaffected groups of farmers, returning soldiers, and trade unions during the election campaign was still in place after the election. Although the Liberals had been returned with a majority of seats in the legislature, the party’s success was probably due more to the disarray of the opposition party, which had been torn apart by corruption scandals and an inability to unify the disaffected groups.31 The grumbling continued after the election and was often directed pointedly at Roberts, sometimes even materializing as obstinate refusal to comply with the Public Health Act that was still known as the “Roberts legislation.” The Act had established district and sub-district boards of health to oversee the collection of vital statistics and the medical inspection of schools, but a year and a half after enactment, Roberts was still trying to activate recalcitrant local officials into appointing “men of good intelligence and favourable to the Act” to the local Board of Health in Kent County. He declared to be “now gone really beyond the length of my tether” and threatened that “every day that [the board of health] is not in operation we are acting illegally, and I cannot and must not further continue along this line.”32 Nonetheless, resistance to the Actpersisted. Roberts’s friend and fellow Liberal MLA, Albert A. Dysart, reported that people in his district of Bouctouche “do not appreciate the beneficent effects and wholesome influences which the Act may engender when put into full operation.”33 Roberts was unwavering in his persistence to impose compliance with the Actand to have local municipal councils pay for public health services. So, for instance, when the Northumberland Sub-District Board of Health was unable to collect $6,000 from the municipal council for services including the sanitary inspection of businesses and the medical inspection of school children, Roberts fumed that he was no longer going “to listen to Northumberland Municipal Council” and intended to collect the amount owed one way or another.34

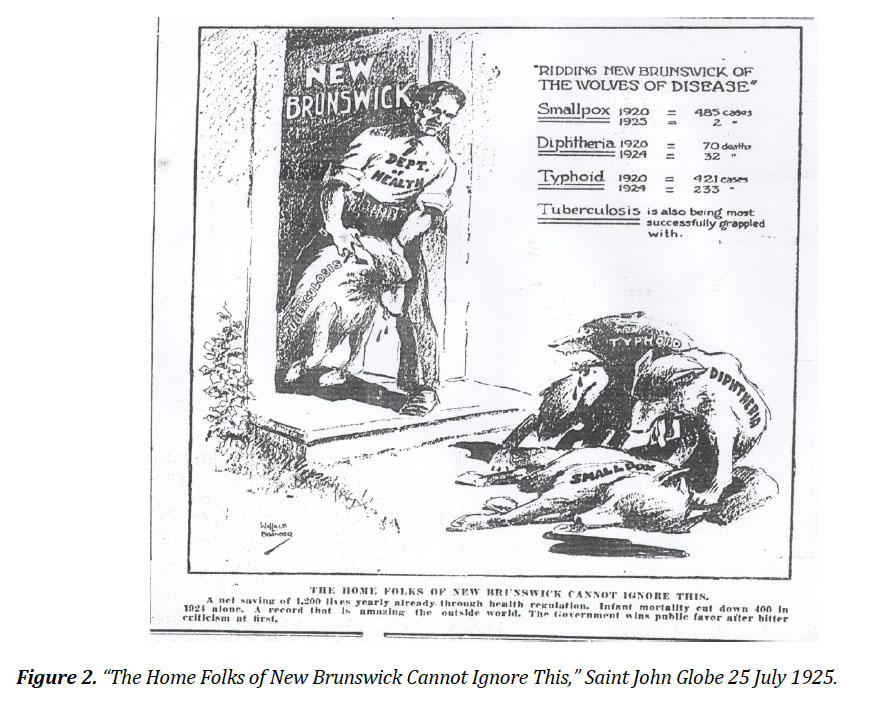

16 Other public health reform measures that focused on essential food commodities like milk and bread were especially unpopular. Citizens complained that Roberts’s interest in reform unfairly targeted poor families who could not pay higher prices and would have to go hungry. But an amendment to the Public Health Act, which gave medical health officers the authority to determine whether bread intended for sale for human consumption was “securely wrapped in suitable paper or other proper material” was passed in 1921.35 Bread prices rose as producers grumbled that they had to buy materials and equipment to comply with the new regulations. But it was Roberts’s push to make it unlawful to sell milk or cream not “scientifically pasteurized to the satisfaction of the District Medical Health Officer” that was the breaking point.36 This new regulation antagonized everyone in the dairy industry, from rural farmers to those who delivered and sold milk in urban centres. Farmers were annoyed that milk cans had to meet certain size and cleanliness criteria set by the Health Department. Milk distributors resented having to invest time and money in sterilization and pasteurization equipment. Citizens worried that the cost of this expensive new process would be passed on to consumers, and wondered again whether poor people would be able to afford milk for their children. Even though complaints persisted that milk sold from open containers in shops was often old, sour, or had dead mice, straw, or manure floating in it, there was nonetheless widespread resistance to Roberts’s efforts to modernize the milk supply. Much of the resistance focused on issues of civil liberty, as consumers argued that they, not the government, had the right to choose whether they drank pasteurized or raw milk. These complaints became a central feature of the 1925 election, and the campaign turned nasty over the milk question. Roberts was again in the crosshairs. He received threatening letters and accusations that he and his family secretly drank unpasteurized milk and that he was financially invested in pasteurization plants.37 Even in the face of an 11,000-signature petition against mandatory pasteurization, however, Roberts remained steadfast and refused to withdraw the regulation. His refusal to waver was characterized as “arbitrary, vicious, …[and]…self-dignified,” but Roberts remained undeterred as Liberal-leaning newspaper drawings tried to shift focus to his role in establishing the Department of Health and “ridding New Brunswick of the wolves of disease”(see Figure 2). Here Roberts is portrayed as the embodiment of a public health record “that is amazing the world” and one that “the home folks of New Brunswick cannot ignore.”

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

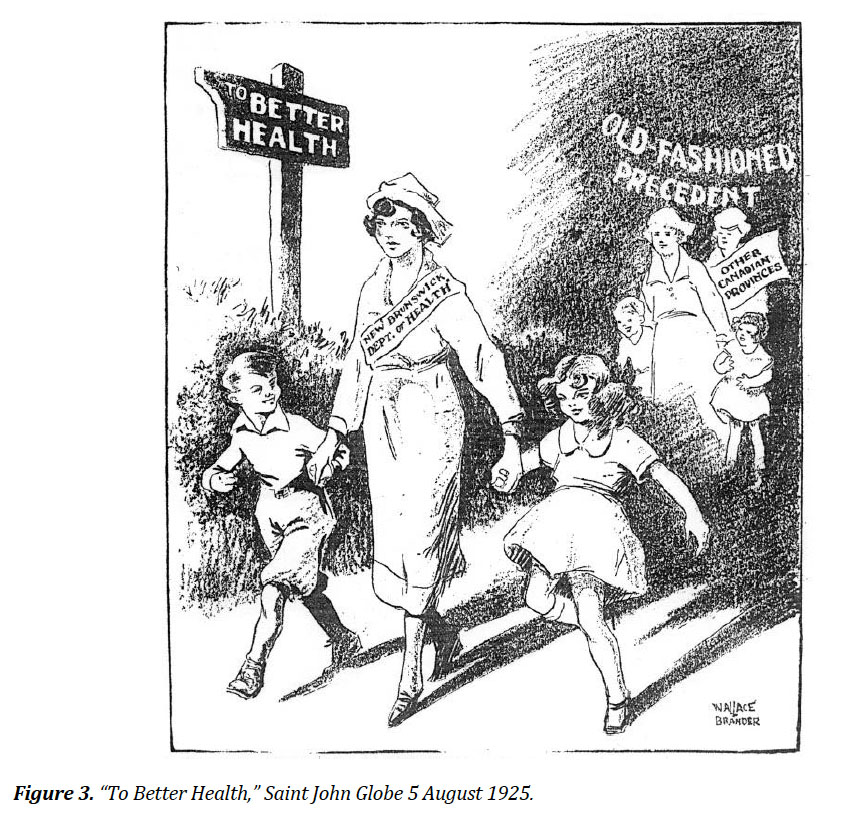

17 Another editorial cartoon, solidifying the narrative of New Brunswick as a leader in public health reform, personified the New Brunswick Department of Health as a nurse, ahead of all the other Canadian provinces and their “old-fashioned precedent,” in leading the happy boys and girls of New Brunswick skipping off to better health.

18 In the end, however, Roberts’s refusal to compromise over the issue of milk pasteurization led to his defeat in the 1925 election and the loss of his position at the helm of the Department of Health.38 The Liberal party was also defeated, with the Conservatives winning a resounding thirty-seven of the forty-eight seats in the legislature. In the end, partisan politics and the opposition of disaffected and marginalized groups stood as a repudiation of not only Roberts and the Liberal party but also of Roberts’s ideological promotion of centralizing progressivism. Following his electoral defeat, Roberts faded from public view and the political stage, returning to private medical practice and redirecting his interest in public health matters to serve as president of the Canadian Public Health Association and president of the American Academy of Physical Therapy.39

19 But the many images of Roberts as the heroic pioneer of progressive modernization did not disappear entirely, nor had these ideals lost their political resonance for New Brunswickers. Roberts’s political interests were reignited when he agreed to run for the Liberals again, this time in the provincial election of 1935. It was during his second stint as a provincial politician that his record was again leveraged as an asset to promote a notion of provincial exceptionalism, perhaps as a means to mitigate the devastating impact of the economic depression gripping the entire world through the 1930s and hitting the Maritime region of Canada particularly hard. Just as Conservative parties had been swept from power in other provinces and on the national stage, the ruling Conservatives in New Brunswick went down to defeat in what was described in one editorial as “one of the greatest political debacles in the history of the province.”40 The Liberals had designed their winning strategy meticulously, noting that while a platform of substantive initiatives to create jobs and build new and better roads was important, the campaign platform was “not as important as the selection of men to lead the party.”41 Enlisting “the best brains” in the province had brought Roberts back to the political fold, and within one year he was again a symbol of progressive health reform, mythologized as a beacon of modernity and progress, and enlisted to carry the province through the difficult times of the worldwide depression.42

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

20 The first opportunity for commemoration came in May 1936 when Mount Allison University conferred an honorary degree upon Roberts. Standing on the convocation platform waiting to receive his degree, Roberts heard the president of the University, A.S. Hatcher, introduce him as one whose “name must be numbered among the pioneers of Empire.” It almost seemed that Hatcher was revisiting the main narrative employed during Roberts’s failed re-election bid in 1925 when he suggested that Roberts was deserving of “the gratitude of every man, woman and child, for he is the founder and builder of the present public health system that guards their lives and their happiness from the menace of pestilence and disease.”43 In his speech to the convocation crowd, Roberts congratulated the university for emphasizing public health by X-raying new students for tuberculosis and by running a compulsory course in personal hygiene. In a province struggling against economic recession and overall decline, there was a need for a redemptive hero, and Roberts filled the role of pioneer of modernity when the province needed that promise. At a time when the province was suffering one pessimistic loss after another, Roberts and his public health reforms were held up as beacons of hope and progress. This kind of political leveraging of Roberts had been on full display earlier in the day of the convocation ceremonies at Mount Allison University when Roberts’s long-time friend Albert A. Dysart (who had since become the premier of the province) addressed the students before they set off to receive their degrees. He paid tribute to Roberts who, he said, “is devoting his whole life to the welfare of his fellowmen,” especially with his latest medical research in the use of radium to treat cancer.44

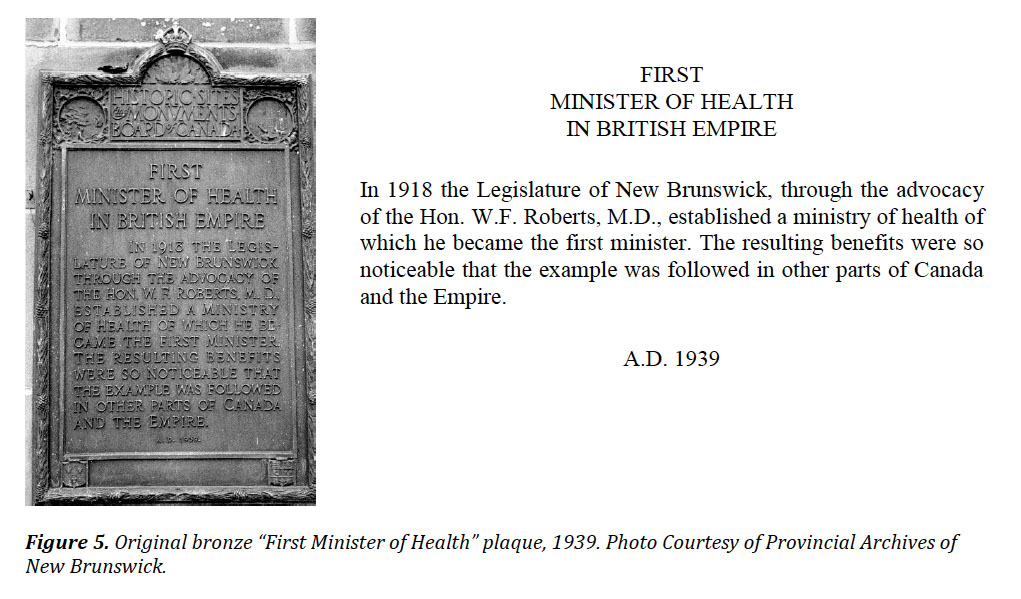

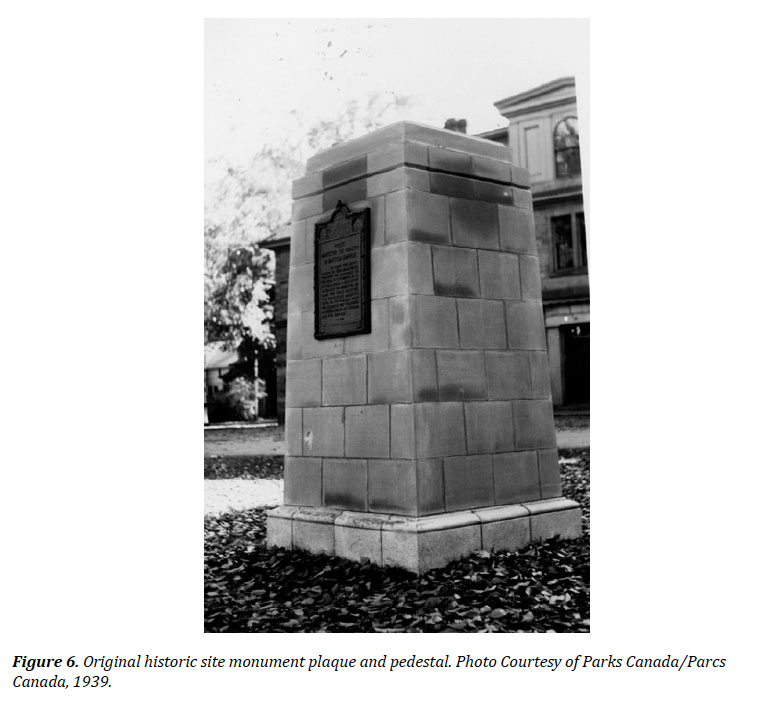

21 The narrative that had been crafted during the 1925 election campaign, which cast Roberts as an iconic hero leading New Brunswick on a path of cutting-edge health care reform that stood as a model for the world, had been re-launched. But this time it was about to be cast in stone. In 1939, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC) approved an application from the government of New Brunswick to erect one of its standard stone-pedestal monuments and dedicate it to the memory of Roberts, who had died in February 1938. Built for prominent exposure on the grounds in front of the legislature buildings in Fredericton, Roberts features prominently in the cairn’s bronze plaque, which is titled “First Minister of Health in British Empire.” The plaque’s text details that “In 1918 the Legislature of New Brunswick through the advocacy of W.F. Roberts, M.D., established a ministry of health of which he became the first minister. The resulting benefits were so noticeable that the example was followed in other parts of Canada and the Empire” (see Figures 5 and 6).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

22 This monument functioned, as all monuments do, as a civic acknowledgement of honour, pride, and accomplishment, a reification of an idealized past standing as a hopeful beacon of progress to the future.45 The power and dignity of the monument’s message was further solidified because it had been approved and built by the HSMBC, which, from its inception in 1919, had functioned as an arm of the federal government dedicated to the shaping of the public’s memory of the nation’s past. This commemoration of Roberts and public health reform in New Brunswick therefore garnered for the province both a sense of national belonging as well as an affirmation of the province’s pre-eminence as an innovator in public health reform.46 This place of priority is clearly on display in the first and only word prominently displayed at the top of the plaque: the boastful “first” is a spotlight cast directly on W.F. Roberts, the first minister of health. This claim of being the first jurisdiction in the entire British Commonwealth to establish centralized government oversight of public health and to appoint the first minister of health was, however, a bold overstatement, an exaggerated narrative that had originated with Roberts himself over twenty years earlier.47 During the spring 1917 fight to win support for his Public Health Act, Roberts had lobbied for votes by telling fence-sitters that their support would win them recognition as first to enact a revolutionary government innovation that would be recognized the world over. And since “firsts,” as McKay and Bates have so brilliantly explained, have “everything to do with progress,” this first, which started as an exaggeration used in a political speech to win a few votes, and which then gained credence in response to an influenza epidemic, ended up launching a mythology of modernity, exceptionalism, and progress that was cast in concrete and bronze, and which would last decades.48

23 The narrative of progress and the conflation of this narrative with W.F. Roberts had been sustained in the decades following the establishment of the Department of Health and the influenza epidemic, and was again on display when Roberts died on 10 February 1938, nine months after a diagnosis of prostate cancer. Headlines on the front pages of newspapers throughout the province that announced his death proclaimed him as the “first minister of health in empire,” that he “established first health ministry in the empire,” and that “empire health leader dies.”49 Hyperbole poured from every article dealing with his death and funeral, echoing the text of the monument and further propping up the narrative that Roberts’s health reform plan “was destined to be the model on which all the health systems in the British Empire, and for that matter the world, were based,” and that he was “a pioneer in Canada in the field of physical medicine,” having pushed through legislation that marked “the first time in the history of Canada and, indeed, of the Empire, a government considered the health of its people of such importance.” It was predicted that “time will not dim his achievement and as years pass generations yet unborn will have cause to bless his memory.”50 Another paper reported that Roberts’s old friend, Premier Dysart, and all his cabinet colleagues also predicted that “his name will live in this province for his imperishable record of public service.”51

The Fading of William F. Roberts as Public Health Hero

24 Roberts’s death in 1938 came at the end of the Depression in New Brunswick, and although the province was experiencing modest economic recovery in the fishery, farming, and mining industries, its future prospects were far from secure.52 While the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to New Brunswick in the summer of 1939 generated wild enthusiasm, the prospect of another European war cast a worrisome shadow over celebrations, even if balanced by projections of a wartime economic boom for the province. With the outbreak of war, provincial economic interests were subsumed under the federal government’s authority in the name of national interest and homeland security. Any sense of distinct provincial identity or self-sustaining autonomy, as had been evoked by the Roberts’s monument, was swept away, and historical awareness of the province as innovator of public health reform faded quickly, leaving only the stone monument as a reminder. And as the pejorative characterization of New Brunswick as “the sick man” of Canada gained silent currency in the national psyche, its own exaggerated importance as the birthplace of government oversight to heal the sick faded from historical consciousness.

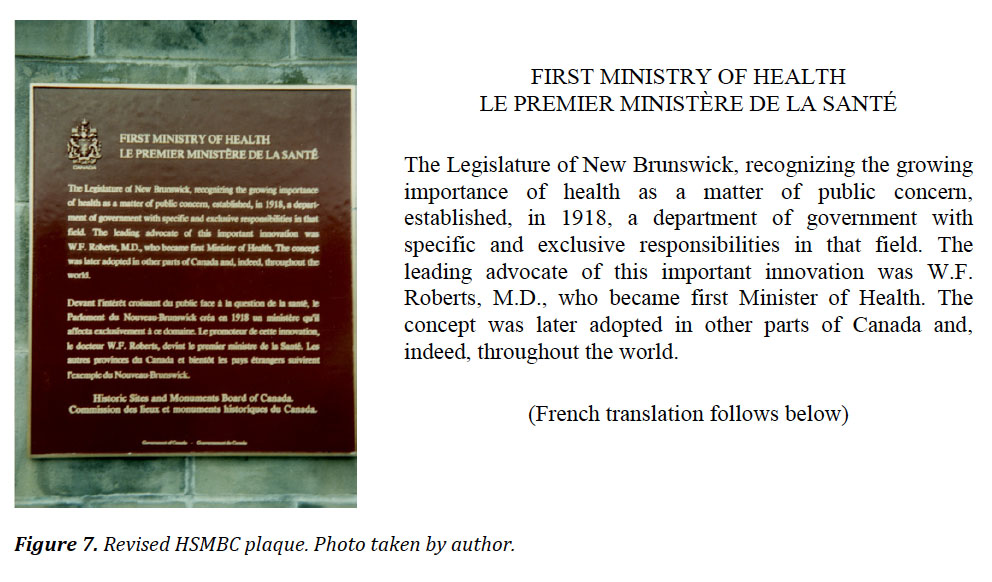

25 Monuments stand as silent sentinels and remembrance of honoured pasts, but the irony is that the pasts these monuments commemorate are neither as durable nor static as the hard stone or granite they are shaped from. The past changes as times change, and monuments and statues are left to be variously lauded, lamented, or forgotten altogether, their value and worth shifting like soft sand in response to social, cultural, and political transitions. So, while the HSMBC monument that designated Roberts as the father of public health reform around the world was a powerfully prominent affirmation of the historical importance placed at that time on the modernizing and centralizing progressivism invoked by Roberts, its message did not resonate for long. Indeed, the strength of the message was weakened and the spotlight on Roberts grew dim when the original bronze plaque was replaced (sometime after 1983) by another plaque with revised text and a new French translation. New interest in bilingualism in Canada, which had sparked passage of the Official Languages Act in 1969, had shifted HSMBC policy to insure that all heritage plaques across Canada appeared in both official languages—and so at some point in the 1980s, the “first minister of health” plaque was revised so as to be aligned with the sociopolitical paradigm of the time.

26 Beyond the addition of a French translation of the text, however, there were three other subtle yet significant changes to the text of the monument’s bronze plaque which make manifest the shifting views of the times and the need to renovate historical memory accordingly. The first revision of the original plaque’s title from “first minister of health” to “first ministry of health” shifted attention from a man to a government department. Credit for the establishment of the ministry of health, which is given to Roberts in the original text, shifts to the legislature in the revised version, proving that when modernization is trumpeted as the product of a government system rather than the work of an individual, heroes are no longer needed.

27 The second change exposes shifting views of the notion of public health itself. The original text highlights the noticeable benefits that resulted from the establishment of a ministry of health, but in the revised version “benefits” has been replaced by the rather anemic “concept” of public health. Time, modernization, and better health care have erased the specific victories of the first department of health, leaving a more normalized, and therefore less remarkable, notion or concept of public health. But perhaps, too, this revision reflects New Brunswick’s rather tepid response to the federal-provincial initiative, launched in the 1960s, to negotiate cost-sharing of a nationwide or universal health care insurance. This program, although an ideological complement to New Brunswick’s so-called Equal Opportunity policies, was resisted for over two years, making New Brunswick the last province to sign on to Medicare, an ironic entrance by the province that had been at the head of the pack when it came to health reform at the turn of the century.53

28 The third revision is to the section of the text describing the impact of New Brunswick’s Department of Health. The original text boasts that the new department was modelled not only in other jurisdictions across Canada but also in “the Empire.” The revised text, however, replaces “Empire” with “world,” thus revealing that the Canadian identity has shed its singular and deep connection to the British Empire and cast off the last remnants of its imperial consciousness. Roberts, who lived when imperial feelings were deeply woven into popular consciousness, faded from popular memory like the fraying fabric of imperial sentiment.

29 A further renovation and then relocation of the stone cairn monument bearing the “first ministry of health” plaque, which occurred more recently during redesign of the legislature grounds (2012–2014), have further eroded historical awareness of Roberts and his legacy in New Brunswick as a leader of public health reform. The revised bronze plaque was moved to a renovated stone pedestal positioned in a different location on the grounds, and three additional plaques were affixed to each side of the newly constructed concrete pedestal. These HSMBC-designated plaques, cast in the 1940s and denoting the historical importance of other provincial leaders—Charles Fisher (1808–1880), Lemuel Allan Wilmon (1809–1878), and Sir Howard Douglas (1776–1861)—were originally affixed to the legislative building itself.54 The public memory of Roberts, as embodied in this stone monument, has once again shifted, losing its original power and significance. The relocation, changes to the text, and addition of other memorial plaques next to that of Roberts, all reveal a shift in historical memory and meaning.

The Lamenting of William F. Roberts as Public Health Hero

30 Before fading in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Roberts’s historical presence briefly cycled back into public consciousness during New Brunswick’s celebrations of Canada’s centennial in 1967. These celebrations, which enlivened modernist narratives, also rejuvenated Roberts’s memory, used again as the rhetorical embodiment of liberal progress just as he had been lauded decades before. This time, the institution known as the Lancaster Hospital School for Retarded Children, located in the west end of Saint John, was rededicated as the Dr. William F. Roberts Hospital School “in memory of Dr. Roberts, a Saint John physician who was the first Minister of Health in the Commonwealth.”55 The rebranded institution, which originally opened two years earlier in January 1965, was considered “one of the most modern of its type in North America and reflects the attitude and interest of the government in the training and care of retarded children.”56 At the time of its renaming it was in full operation as a residential institution providing a combination of hospital and educational services to assess, treat, and train (or socialize) children from across New Brunswick with mental and physical disabilities or with so-called deviant behaviours. Staff provided physical therapy as well as rudimentary educational and skills training for children ranging in age from six to sixteen years of age.57

31 After less than twenty years of operation, however, the government announced the closure of the institution in November 1984, and it was closed permanently in December 1985. The recommendation to close, made in a report commissioned by the New Brunswick Department of Social Services in 1984, was followed up with a recommendation that services for children with disabilities should be provided in community settings across the province. This marked an ideological retreat from the notion that large institutions in central locations were the best way to treat mentally and physically “abnormal” children, a notion that, by the mid-1980s, was increasingly thought to be “only of limited help at best and positively harmful at worst.” Replacing this approach was a growing conviction that children with special needs should be fully integrated “in a normal environment” in schools and with their own families and communities. What was needed was “a dynamic, community-based service network for disabled children and families in their own region of New Brunswick.”58 Clearly, centralization was no longer considered a tool of modernization.

32 Accompanying this widespread ideological swing away from centralized institutionalization to community integration was a growing “sense of unease within the WFR [the W.F. Roberts Hospital School]” itself.59 While this general impression of institutional anxiety was identified in the 1984 report as being the consequence of administrative inefficiencies, mistrust, and poor training, darker secrets about the abuse and neglect of child residents began to emerge in the early 1990s. Rumours grew that staff had abused residents of two of the province’s training institutions for young people, the Kingsclear Training School outside Fredericton and the W.F. Roberts Hospital School, and a provincial inquiry proposed a program of compensation for victims.60

33 In 2016, when Ann-Marie Tingley, the past president of the New Brunswick Association for Community Living, was awarded the Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers by Canada’s governor general, she recounted her efforts to close institutions like the W.F. Roberts facility in the 1980s, characterizing the times when children with disabilities were institutionalized as a “dark period of New Brunswick’s history.”61 This time, when Roberts’s name was invoked, it was synonymous with the shame and notoriety of child abuse occurring in residential institutions across the country. Originally established as symbols of progress and modernity, these institutions are now viewed as dehumanizing reservoirs of abuse and neglect.

34 This repositioning is on clear display in briefing notes outlining the government’s position on special education. Written in 2005, they confirm that “Today, in New Brunswick, there are no more special classes or institutions, and all students are enrolled in a regular class at a public school. New Brunswick is seen as a leader in the area of school inclusion both nationally and internationally. The different education stakeholders and the general public support the principle of inclusion, and no one wants to turn back.”62 Certainly, no retrospective lens scanning the past for justification of this perspective would want to pause over Roberts’s promotion of centralized government oversight.

35 Still standing today, the former Dr. William F. Roberts Hospital School, with his name still prominently displayed on the building facade, has been converted into commercial, retail, and low-rent space for non-profit organizations. In an ironic twist that veils its dark history, the building is known today as the Maritime Opportunity Centre.63

36 While some aspects of the past matter to Canadians and to New Brunswickers, the past we remember and commemorate changes along with the times we are in. A recent survey that set out to understand just how much Canadians (and New Brunswickers) care about, or use, the past concluded that “Canadians use history to situate themselves in the present and plan for the future.”64 Individuals scour genealogy records to track down family roots and build family trees; the cultural crafting of a wider collective memory mythologizes those pieces of the past that reverberate in the present. So, when the past no longer echoes in the present, collective memory loss sets in. Following this pattern, the legacy of W.F. Roberts as a leader of public health reform in New Brunswick has faded from public consciousness.

37 This case study shows that notions of health and attitudes about the role of government in the health of its citizens have not been static or unchanging but are instead a reflection of historical contexts and narratives. Integration of this kind of historical awareness into the process of crafting policies for the future of the province’s health care system has several potential benefits. An historical lens offers insight into what was possible, what worked or did not work in different situations or locations, and what unforeseen consequences or reactions arose in response to different policy decisions. This is not a mere prosaic claim about learning lessons from the past, but rather about using the past to understand where we are and how we got here so that we may move forward with as much insight as possible.