Refereed Articles

Call the Doctor?

Understanding Health Service Trends in New Brunswick, Part I, 1918–1950

This article initiates an online discussion of health service trends in New Brunswick over the course of the twentieth century. It sets the stage by describing changes in physician service access, examining registration data from the American Medical Directory for 1918 and 1950. When comparing data sets, three distinct trends emerge. First, we see the centralization of physician services in larger population centres, especially those communities with larger general hospitals. Second, a more equitable physician per population ratio between anglophone and francophone, southern and northern, regions of the province in 1950 as compared to 1918 is evident. Finally, the transnational Canada-U.S. border becomes more important in defining physician career paths (especially medical and post-graduate education) as the twentieth century unfolds.

Le présent article amorce une discussion en ligne des tendances en matière de services de santé au Nouveau-Brunswick au cours du XXe siècle. Il ouvre la voie en décrivant les changements liés à l’accès aux services médicaux, à l’examen des données relatives à l’enregistrement du American Medical Directory pour 1918 et 1950. Quand on compare les ensembles de données, on voit que trois grandes tendances émergent. D’abord, on voit la centralisation des services fournis par des médecins dans les grands centres urbains, notamment dans les collectivités ayant de plus grands hôpitaux généraux. Ensuite, on note qu’il est clair qu’il y a une répartition plus équitable de médecins entre les anglophones et les francophones, entre le nord et le sud de la province et entre les régions de la province en 1950 comparativement à en 1918. Enfin, la frontière entre le Canada et les États-Unis devient de plus en plus importante dans la définition des plans de carrière des médecins (particulièrement la formation médicale et les études supérieures) à mesure que nous avançons dans le XXe siècle.

1 Many newcomers to New Brunswick are dismayed to find themselves on a lengthy wait list for a family doctor. A government registry, which “places” new residents of the province with family physicians once space in a practice becomes available, is backlogged with residents waiting for care. The New Brunswick Medical Society’s website reports there are at least 50, 000 New Brunswickers without a family physician in 2017. “Like many other jurisdictions in Canada,” they write, “there are simply not enough physicians in New Brunswick to serve the patient population” (New Brunswick Medical Society).

2 The question of “how many doctors are enough” is a longstanding historical issue. In the nineteenth century, both British and North American medicine was, by most accounts, often overcrowded with doctors (Stevens; W.J. Rothstein, American Physicians; Loudon). Then, turn-of-the-century reforms of medical education effectively closed down many schools, causing a contraction in the supply of physicians and ushering in a period of tighter professional control over the interwar medical marketplace (Burnham). Historians have described the 1920s and ’30s as an “age of equipoise” for most general practitioners in Canada, a period when the status of general practitioners reached a peak; rivalry from unlicensed practitioners had been contained or eradicated, and specialization had yet to emerge as a competitor in practice (Shortt, “Before the Age of Miracles”). But there were problems for patients. In her classic study of specialization and health resource allocation in mid-century America, Rosemary Stevens explains how the distribution of physicians over the social fabric began to disproportionately favour urban areas, and acknowledges that medical services were unequally distributed by income and region. “With greater specialization of facilities and personnel, such inequities were becoming more acute….Small towns and villages could not support the services of specialists, even if they could lure the specialists away from the intellectual attraction of the major urban centres” (Stevens 276). As a result, the difference between urban and rural health services, particularly the problems with physician access that had been a source of anxiety as early as the 1920s, became even more marked in the Depression and after the Second World War (Stevens). At the same time, the importance of accessing physicians became critical to accessing health care.

3 Historical work on physician access in New Brunswick has, to date, focused on biographies of physicians situated within the context of professional organizations, or treated physicians as actors within the history of a given hospital (Stewart; Handa). We deploy the tools of social history research in order to understand health history in the province from the community perspective, offering a quantitative analysis here as a prelude to a more qualitative account. In this we add to research that critically examines the longstanding historical difficulties in finding, or even determining, what “enough” doctors looks like in the medical “ecosystem” of a given place and time (Connor et al.). Questions about physician access are linked to questions about infrastructure. How many doctors are needed for a community that is home to a large general hospital? Hospitals tend to centralize physician services and medical work—a well-outfitted hospital may offer the best elements of medical science for the purposes of patient care. But can the efficiencies of modern centralized hospital care actually replace physicians, requiring fewer of them in a medical system?

4 Physician access and health service needs relate to place and culture. What about a community that is geographically remote—what kind of health services serve, or have best served, those contexts? What about communities that, for whatever reason, might resist the implementation of health services along a medical model? How many doctors are required for communities that are otherwise well-served by local, “lay,” or alternative health care providers, such as First Nations’ communities that may have their own forms of midwifery and home care? Alternatively, do some communities remain underserved because the state “assumes” other institutions are providing critical care, as with the Catholic Church’s hospitals in Acadian New Brunswick? And then there are questions of inter-professional overlap. How many doctors are required for communities that are otherwise well-served by the public health system, with access to highly trained public health nurses? What constitutes “adequate” care? A close examination of variations within physician services in the province reveals gaps and outliers in service structure that excite curiosity and invite analysis. The search for answers leads us down a path that reveals the complexities of serving the diverse communities of this province, a province with a complex “medical ecosystem.”

5 By the early decades of the twentieth century, physician organizations actively encouraged professional consolidation, including tightening credentials for practice and supporting reforms in medical education that led to implementation of a full-time, science-rich curriculum. New Brunswick had no provincial medical school, so professional consolidation efforts focused on credentialing and on tracking licensed members within the province. These efforts generated historical records that help historians understand the social distribution of health care services in twentieth century New Brunswick. Using medical directories meant to capture and track the credentialed and licensed doctors, this paper examines the shifting geographies of physician distribution in the province from 1918 to 1950, a critical moment of professional consolidation (American Medical Association 1918, 1741–1746; 1950, 2129– 2134). We use American Medical Directory, which includes the professional licensing information of all states and territories of the United States, as well as Canada and Newfoundland.1 Medical directories allow us to chart and map various elements of physician demography: geographic distribution, distribution by population, and type of training. Our starting point, 1918, marks approximately ten years since the North American directory began publication, and the data captured is more reliable at this juncture than it was when the directory first went to press.2

6 These decades saw significant social and economic challenges—including economic instability and out-migration of the interwar period, the Great Depression, and the Second World War—spanning the early years of post-war population and economic expansion. Passage of a new Public Health Act in 1918 created a designated department and minister, the first in the British Empire (Jenkins). In addition to centralizing power under a designated minister of health, the new Act created three districts: Newcastle, Fredericton, and Saint John—each with a district medical health officer. The decades that followed have been described as “boom years” for the expansion of health care facilities in the province, including both public health nursing services (Kealey) and hospital infrastructure (New Brunswick Department of Health, Study, 3, 9–11).

7 Our investigation into this important period in New Brunswick’s health history prompted more questions than we are able to answer. The most important questions of health service access can only be answered by combining the local, community record against the changing picture of professional demography. While demography offers insights, it is incomplete. This paper marks the beginning of a historical project to round out and understand the tricky question of physician access over the twentieth century. As such, it sets a starting point for understanding health care access in the province more broadly. It represents the first of a series of three articles designed to offer opportunities for everyday New Brunswickers to fill in the details of what will become a “crowd-sourced” picture of health service distribution in New Brunswick over the course of the twentieth century. At the end of the series, we will offer a clearer picture of the ways in which physician availability intersects with local experiences with health service access across the province. After providing this snapshot of the social distribution of doctors, and offering context relevant to the major health policy goals of the period, we will invite and welcome local stories of health care that help make sense of the broad trends we reveal here.

8 There are many ways one might conceptualize the twentieth-century history of health care. For this project we have selected three important periods in health service history. This first contribution launches the century-long investigation by examining the end of the First World War through to the end of the Second World War. The second covers the “Medicare implementation” years, surveying the distribution of physicians from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s. A final article will examine the history of health service regionalization, covering the mid-1970s through to the turn of the twenty-first century. In each case, we will present an article that outlines the key changes in physician demography set against the social history of health care for that period of New Brunswick history. We will then invite members of the general public, with their various insights into the construction and expansion of community hospitals, access to family and local historical sources, and perhaps their own memories of health care services (as practitioners in service or members of the public served) to offer their specific, local anecdotes and material to round out this history. These will be captured in a year-long, bilingual, moderated discussion forum set up by the Journal of New Brunswick Studies, and collected into a second e-publication.

Professionalization and Medical Dominance

9 Formal physician organization in New Brunswick dates back to 1880, with the creation of the province’s first medical society (Grove). By the turn of the twentieth century, the Medical Society of New Brunswick had established educational standards and had begun consolidating the profession by ensuring that all medical doctors were registered and held a formal license. These activities were supported by national organizations. Since its formation in 1912, the Medical Council of Canada advanced a single standard examination for Canadian medical school graduates and licence (LMCC). In 1929 the national Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons “set up mechanisms to certify specialists and accredit specialty training programs” for both medicine and surgery (McPhedran 1536). By the interwar period, most provincial medical licensing authorities, including in New Brunswick, accepted the LMCC as a criterion for awarding licenses. New Brunswick seemed to generally accept the certification from the national college, but the provincial College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Medical Licensing Board, which regulated licenses for that body, retained a great deal of discretion over credential transfer. Interwar regulation of physician licenses meant that the college did not automatically accept the LMCC, for instance, if applicants were interwar immigrant physicians from countries the Canadian government considered “enemy aliens” (Weaver). But because tracking physicians and monitoring credentials were increasingly important, provincial medical societies and their colleges were encouraged to work in cooperation with national organizations.

10 Credentialing and licensing went hand-in-hand with the standardization of education and practice. North American historians have recognized the realities of nineteenth-century medical pluralism, which created longstanding patterns of inter-professional collaboration, as well as competition, among health care providers. Before the rise of scientific medicine at the end of the nineteenth century, most maladies were treated at home by women, who may or may not have called in a medical practitioner to assist in the care of their families and neighbours. If they did call in someone, the practitioner may or may not have been trained in “orthodox” medicine.

11 Members of the “regular” New Brunswick medical profession, a group sometimes referred to as “allopathic doctors,” argued over much of the nineteenth century that the province needed “fewer but better” health care practitioners and more means to regulate dangerous practices of medical “quackery” in order to protect a credulous public (Twohig). The realities of competition from sectarians—including, but not limited to, homeopaths, eclectics, various “botanical” healers and midwives—within the nineteenth-century health care marketplace encouraged regular physicians to engage in professionalization. Doctors created or joined medical societies, encouraged and supported the passage of medical licensing laws restricting the paid practices of health care—all efforts initiated and strongly promoted by regional medical elites (Howell, “Elite Doctors”; Mitham). This solidified what some call the “medical dominance” of physicians within the health care hierarchy in Canada, a hierarchy solidified between the First World War and the era of Medicare (Friedson; Coburn et al.; Kenney).

12 By 1918, the reforms in medical education had an impact on the training of physicians in New Brunswick, and likely also influenced physicians’ social organization. Physicians in the province were trained through standardized curricula in an increasingly institutionalized, science-based, six-year training model, complete with internships and residencies attached to teaching hospitals. This replaced the shorter and much less expensive medical training on the “proprietary model”: part-time and casual medical education that often culminated with apprenticeship to a physician-mentor. While these reforms began in the 1870s, the effort to standardize medical education culminated with the famous 1910 Flexner Report (Flexner). This survey of medical schools in Canada and the United States, written by education reformer Abraham Flexner for the Carnegie Foundation, offered a candid assessment of medical education, heaping praise on some, such as McGill, while indicting others, such as the Halifax Medical College. Such reforms, especially when examined in light of the broader aims of the physician professionalization process, have been described as a sort of “monopolistic impulse” on the part of physicians (Howell, “Reform”). By 1918, the effects of the reform movement could be felt across the profession, and medical directories capture a moment when the older physicians who were largely trained for practice were being replaced with a “new style” of doctor who was trained in medical science, groomed for the hospital and the clinic (Howell, “Medical Professionalization” 5–21; Shortt, “Physicians”).

13 By 1950 these changes were largely complete, and so examining physician demography between 1918 and mid-century renders a picture of how such reforms changed the profession, capturing the early post-war stages of what Paul Starr has famously called the “social transformation of medicine.” This transformation ultimately created a vast system of health care, the “medical industrial complex” of the later twentieth century, a process accompanied by significant investment in hospital infrastructure and the advent of third-party payers in health care, usually through public or private forms of health insurance. By 1957, all Canadian provinces, including New Brunswick, would be pulled down a path toward universal health care with the federal Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act (HIDS). This Act provided coverage for most forms of hospital care for all Canadians, and paved the way for free physician services under Medicare a decade later (Taylor, Health Insurance; Maioni; Naylor; Marchildon, “Policy History”). The year 1950 is a good one to measure the influence of relatively unhampered market forces in health care, a context some have described “medical liberalism” (Marchildon and Schrijvers). Though medical education reform in Canada depended on philanthropic efforts of organizations like the Rockefeller Foundation (Fedunkiw), the distribution of physician services—increasingly the crux of health service and the point of access—was largely left to the open market as physicians continued to make their medical living on a fee-for-service basis. What did physician access look like at this moment, after a period of professional reform but before the incursions of the welfare state?

14 When comparing 1918 and 1950 data sets, we see three distinct trends important to understanding private practice in New Brunswick over the first half of the twentieth century. First, and unsurprisingly, we see the centralization of physician services in larger population centres, especially those communities with larger general hospitals. Second, there is evidence of a more equitable physician per population ratios between anglophone and francophone regions of the province in 1950 as compared to 1918, an important improvement in a linguistically divided province. Finally, the Canada-U.S. border becomes less permeable to physicians; indeed the transnational border becomes more important in defining physician career paths (especially education) as the first half of the twentieth century unfolds.

Physician Demography—The Consolidation

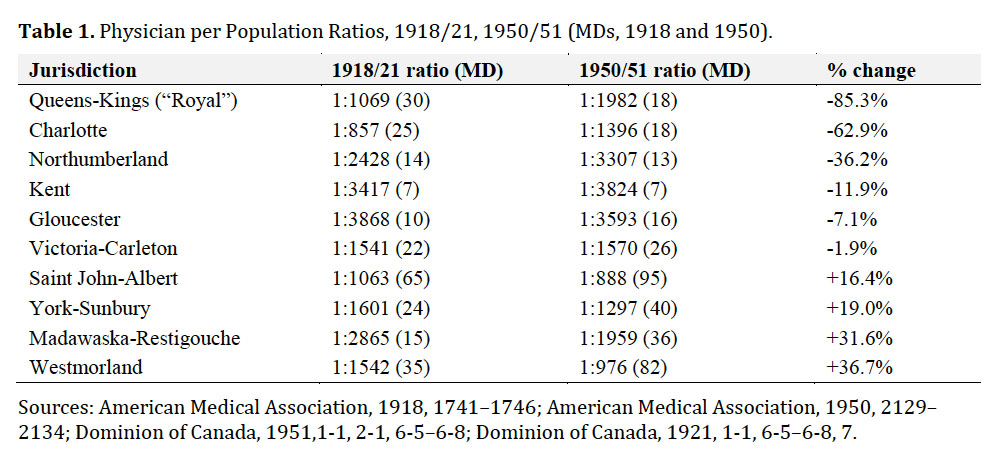

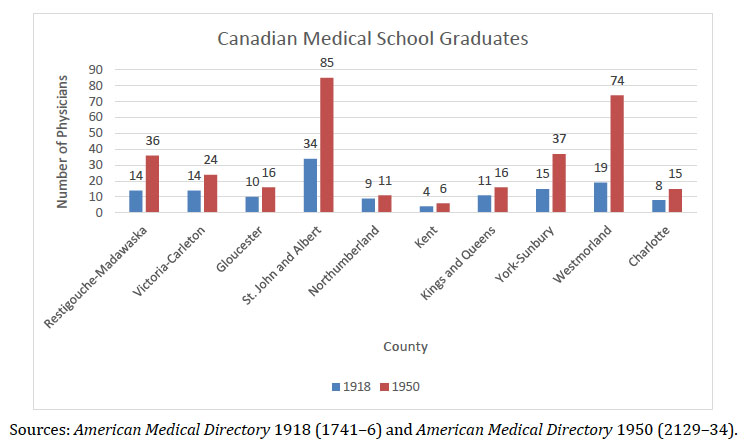

15 The number of physicians per population in the counties of New Brunswick grew quickly between 1918 and 1950, from 247 to a professional cohort of 351 licensed doctors. While the population of the province as a whole was also growing quickly, an estimate of the physician per population ratio shrank from 1:1573 to 1:1469 over these decades.3 But this overall improvement in the distribution of doctors masks disparities in physician services among the regions of New Brunswick. These are captured in Table 1, ranked top to bottom in order from greatest loss to greatest gain in the physicians per population ratio among county-based population areas in 1918 and 1950.4 The table also notes the actual number of physicians for each population area.

Display large image of Table 1

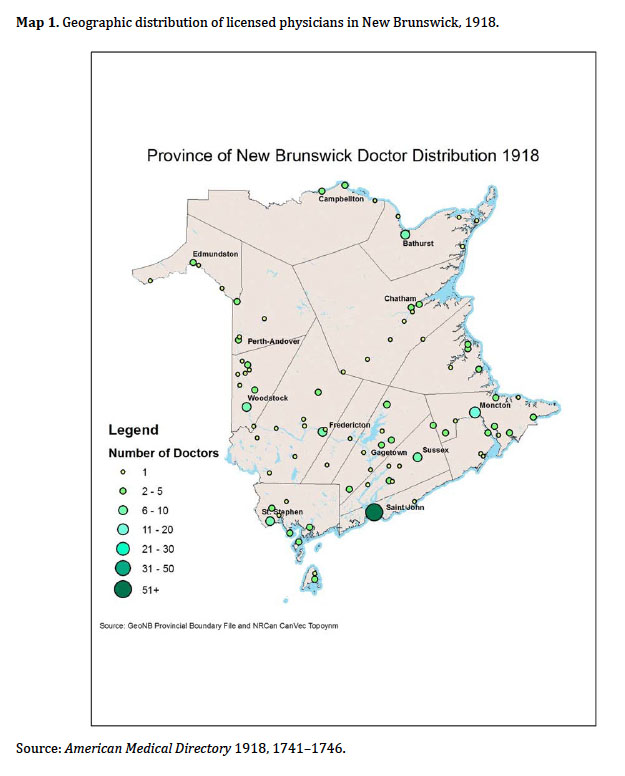

Display large image of Table 116 At a time when the national ratio of physicians per population was approximately 1:1000 (Willard), New Brunswick’s distribution of doctors in 1918 was far from the mark, overall. The southernmost counties enjoyed a better-than-average physician per population ratio, with the population centres of Queens-Kings, Charlotte, and Saint John-Albert falling below the provincial ratio 1:1573. Three county jurisdictions—Westmorland, York-Sunbury, and Victoria-Carleton—had about an average number of physicians per population as compared to the provincial average. And the northern and northeastern counties—Madawaska-Restigouche, Northumberland, and Gloucester—struggled with only about half as many physicians per population as the other parts of the province. The divide between north and south was stark, disproportionately affecting rural francophone areas of New Brunswick.

17 By mid-century, the situation evens out considerably, although disparities remained. Additionally, the perceived health service needs of a growing modern health system had expanded. At this time, an acceptable ratio of physicians per population for any given province or state was set at 1:650 by the World Health Organization. It is worth pointing out that no jurisdictions in New Brunswick met this benchmark. The growing complement of physicians in Westmorland and the steady growth in the largest urban area around Saint John bring the southern and southeastern urban part of the province closest to this threshold. However, outside of Westmorland, most francophone populations continued to suffer from a dearth of physicians. The worst physician per population ratios are in Kent, Gloucester, and Madawaska-Restigouche, areas with large rural and francophone populations. Northumberland County also had an unfavourable ratio. Although its population is more ethnically mixed, Northumberland seemed to share the fate of the francophone counties. This points to another trend: a growing rural-urban split is discernible. The massive (85 per cent) loss of physicians in Queens and Kings Counties, whose medical population went from thirty to eighteen physicians between 1918 and 1950, even as the population expanded, is the starkest example of this trend. The larger towns of the north and northwest are growing, by comparison. Madawaska-Restigouche saw close to the most impressive gains in physician access over these decades, but these were mostly in the towns of Edmundston and Campbellton.

18 But the county-level data mask other trends in physician demography, explored in greater detail below. Some areas—particularly if they were relatively prosperous districts with no urban areas to draw a clustering of physicians—saw little change. It may be because these borderland counties were not proximate to urban areas, which seem to drive the physician population growth over these decades. Victoria and Carleton Counties, for instance, saw hardly any change in the ratios between 1918 and 1950. The urbanization and centralization is evident in counties where weakening overall physician per population ratios hide community gains, especially for larger towns and cities. Northumberland County had a 36 per cent decline in its physician population, but its largest population centre, Newcastle and the surrounding area, saw the physician population rise from three to six over the same period. Similarly, in Gloucester, the medical population went from ten to sixteen doctors between 1918 and 1950, but the gains went to the largest towns of Bathurst (2) and Tracadie (4). The rest of Gloucester continued to experience the worst physician per population ratios in the province. For this reason, we should take the time to go beyond county population data and consider the distribution of physicians through the actual geographies of a county or region, and through urban and rural districts. These are rendered in the following maps that show the geographic distribution of physicians in the two years under consideration.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

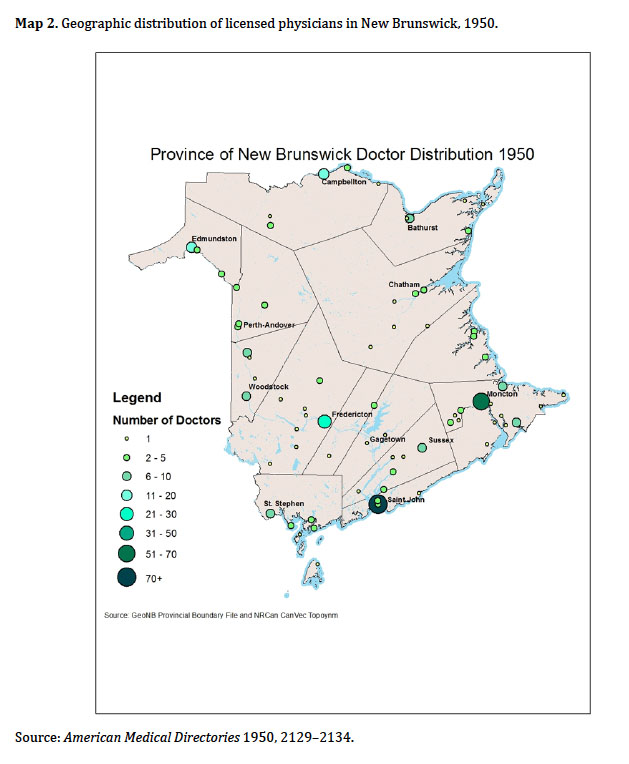

Display large image of Figure 219 Map 2 shows both an overall increase and a clustering of physicians in the northern regions of New Brunswick. In 1918, there were twenty-five physicians scattered over twelve communities in Restigouche, Madawaska, and Gloucester counties; in 1950, there were fifty-two physicians distributed over thirteen communities. Some moving between and among small towns is evident: Kedgwick and St. Martins gained resident physicians over this period, for instance, but Petit Rocher lost their local doctor. But our first observation is that the gains in the overall number of doctors went disproportionately to the larger population centres. Second, we consider the largely anglophone counties on the border with Maine: Victoria, Carleton, and Charlotte. In 1918, there were forty-seven doctors distributed over this region, serving out of twenty-two communities in a largely decentralized manner; in 1950, by contrast, forty-four physicians were distributed over fifteen communities. Here, the largest concentration of physicians in 1918 were in St. Stephen and Woodstock, home to seven and six physicians respectively. In 1950, St. Stephen lost a doctor, Milltown went from three to two, and Hartland went from two to one. Castalia, Grand Harbour, Moores Mills, Oak Bay, Centreville, Florenceville, Lakeville, and Rolling Dam all lost their single resident physician. By contrast, Woodstock gained two doctors and Perth and Plaster Rock went from one to two physicians each. Blacks Harbour got two physicians and a community called North Head received one. One interesting outlier to this centralization trend is in the community of Bath, where the physician population jumped from two resident physicians to seven. There is no real explanation for this increase emergent from the data, underscoring the need to consult qualitative social history sources to make sense of some micro-changes to the physician landscape. But, overall, physician services were undergoing centralization.

20 Physician concentration is also observable elsewhere in the province, though not as pronounced in the central anglophone counties, including York County where the capital city of Fredericton is located. Canterbury Station and Hawkshaw, Meductic, and North Devon in York and Sunbury Counties of central New Brunswick all lost their resident physicians, while Millville lost one of two. Minto, by contrast, gained two, somewhat offsetting the rural redistribution of physicians over these decades. But the real jump was in the number of physicians in Fredericton, up from ten in 1918 to twenty-nine in 1950. Almost all the new physicians listed in 1950, as compared to the roster for 1918, came to the capital city. The southern anglophone counties, such as Saint John and Albert, witnessed similar trends. These counties had sixty-seven physicians in 1918 distributed over eight communities.5 By 1950, the medical geography had shifted to ninety-five physicians in five communities, the starkest rendering of this centralization trend.6 The towns of Albert and Harvey lost their resident physicians over this period, and Hillsborough went from two to one doctor. But Saint John itself, the largest municipality in the province, went from fifty-five physicians to eighty-seven physicians over the same period.

21 Finally, consider the eastern counties, home to a combination of anglophone and francophone populations: Northumberland, Kent, and Westmorland. In 1918, there were fifty-six physicians spread out over nineteen communities; in 1950, there were 102 physicians spread over twenty-three communities. In Northumberland, Red Bank gained a physician, but Nelson, Boiestown, and Derby lost theirs. Kent County had the same number of doctors (7), but Fords Mills lost a doctor, while the two physicians in Richibucto were joined by a third. In Westmorland County, the concentration was very marked. Among the smaller towns and rural areas of Westmorland, only one community, Cape Bald, lost their resident physician. Saint-Joseph and Port Elgin lost one doctor each, although they were still served by a resident physician in 1950. Bayfield and Dieppe, on the other hand, gained a resident doctor in 1950, as did River Glade and the Glades sanatorium (TB physician). Sackville went from five resident physicians to nine, Petitcodiac went from two to three, and Shediac went from three to seven. But the biggest change was in Moncton, a city which experienced a sort of physician “boom” over the interwar and immediate post-war period: eighteen physicians in 1918 exploded to a physician population of fifty-four by 1950. As compared to the northern parts of the province, the concentration in the southern more thickly settled part of New Brunswick is obvious, though more of the rural areas kept their resident physicians in the south. The overall number of doctors expanded, the distribution largely widened (with some exceptions) in favour of the larger urban areas. Of the cities in New Brunswick, Moncton saw the biggest increase in the number of resident physicians.

22 The case of Moncton encourages us to pay special attention to the urban areas of the province when trying to chart and understand trends in physician concentration. Moncton seemed to attract and retain more physicians than other communities over this period; its physician population increased threefold between 1918 and 1950. It appeared to draw physicians to the southeast region generally, creating a critical mass of services that perhaps made rural practices in adjacent areas viable and appealing. Fredericton, the capital, was not far behind. The number of physicians in the capital grew from ten in 1918 to twenty-nine in 1950, just shy of the threefold increase of Moncton. Saint John had fifty-five physicians in 1918, by far the largest concentration of doctors in the province.7 While members of the medical profession in New Brunswick’s largest city did swell to eighty-seven in 1950, this increase is only half as significant as Moncton’s experience. But in all cases, the growth of physicians in the cities was in excess of population increase. While the population of Saint John increased from 42,000 to just under 50,000 people between 1918 and 1950, Moncton grew by approximately as many individuals—just over 8,000 new people—but the proportional increase from 11,345 people to just over 20,000 saw the urban population of Moncton almost double. Fredericton went from a large town of 7,208 to a slightly larger 8,830 over the same period. The rapid and significant increase in physicians in the three urban areas of New Brunswick, an increase that outstrips population increase, highlights the swift centralization of physician services that occurred over the space of a generation.

23 This centralization of health services also followed industrial expansion in places that saw less dramatic but also a significant increase in the number of physicians: Campbellton, Edmundston, and Bathurst. For instance, the increase in physicians clustered in the Chaleur region in Gloucester County shown in Table 1 relate to industrial and infrastructure expansion. Bathurst was a trade hub for the surrounding areas and a nineteenth-century shipbuilding centre for the Cunard shipping company. The economy began to diversify in the early twentieth century, and the Bathurst Power and Paper Company opened the area’s first pulp mill in 1914. Pulp and paper became the mainstay of the Chaleur regional economy for the next several decades, representing one of the first forays into a new industry that would come to dominate the provincial economy (Parenteau). Forest products were followed by mining activity, when Bathurst Iron Mines opened operations from 1902 to 1915, with another brief interlude in the 1940s, but these were relatively minor diversifications in local industry.8

24 Bathurst remained a “pulp and paper town” until the post-war era. Indeed, it was one of the earliest beneficiaries of the most significant industrial development that would take place in the province in the twentieth century. As Bill Parenteau has shown, this was the “first modern, vertically integrated industry” in the province’s history, and it allowed for “unprecedented concentrations of natural resources, capital, production and employment” (6). It brought higher wages and reshaped the social fabric of the province (Johnson). Bathurst was one of several regional hubs that benefitted from the expansion of many public services, including hard-surface roads, rural electrification, and schools. These developments were part of a post-war effort at “narrowing the gap in welfare offerings,” as Ernie Forbes put it, between wealthier and poorer parts of the province, a disparity that often fell along ethnic-religious lines (Forbes, 205–206). Indeed, investment in the “public power” movement of the 1920s was a strategy that dominated state economic planning and incentive strategies from 1940 to 1960 (Parenteau; Beach; Kenney and Secord; Armstrong and Nelles). In the case of Bathurst, it translated into communities that were better able than most to draw and hold medical practices.

Hospitals and Physician Centralization

25 Hospitals became increasingly important in attracting physicians to a given area and help explain the drift of interwar doctors. In 1918, New Brunswick was home to twelve hospitals. By 1950, New Brunswick was home to forty-nine. These included a large Provincial Hospital for Nervous Diseases, an institution that emerged from an early nineteenth-century asylum, the first to have been built in what is now Canada (Francis). Also included were five tuberculosis sanatoria: the Jordan Memorial Sanatorium (1911) in River Glades, the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital (1914), the Sanatorium Notre-Dame de Lourdes de l’Institution Lady Dunn (1931) in Vallée-Lourdes, the Moncton Tuberculosis Hospital (1941), and the Sanatorium de Saint-Joseph (1945) in Saint-Basile. But the biggest change was in the number and capacity of public general hospitals, institutions that seemed to spring up everywhere in response to local need and community effort. Looking back on the first half of the twentieth-century hospital boom from the perspective of 1951, the provincial Department of Health agreed, observing, “Most hospitals had developed to meet the needs of specific communities” (New Brunswick Department of Health, Province). But by mid-century this was presenting administrative challenges, including “a lack of cooperation and coordination between institutions…[and] a lack of proper standardization” (Health Care, 6, 11; New Brunswick Department of Health, Province57; Taylor, “Government Planning”). This observation suggests the importance of place in determining the organization and structure of health services into the 1950s. Though seen as “inefficient” at mid-century, such community hospitals—depicted as embedded, organic institutions—emerged as ad hoc responses to local health needs. And they were administered by a wide array of organizations that reflect ethno-religious divides in the provision of care (McGowan). The role played by religious orders, for instance, was very important, and reflects the significance of place in health history over these decades; many religious orders, even those founded for other purposes, became involved in hospital construction and management (Landry; McGahan). This focus on community needs undoubtedly influenced physician demography and access as well.9 With the advent of federally funded universal health care for hospital (1957) and physician (1968) services, health care reform along regional lines would begin to standardize the provincial hospital system and affiliated physicians’ practices.

26 In the 1918 Directory, nine of the twelve institutions listed in New Brunswick were general hospitals. The largest, the Saint John General Hospital with 145 beds, was in the province’s largest city. Saint John was also home to the Provincial Hospital for Nervous Diseases, a large facility with 630 beds for “nervous and mental health care,” and a tuberculosis sanatorium, the Saint John County hospital, a fifty-four-bed facility in the east end of the city. The other hospital for tuberculosis cases offered forty beds at the Jordan Memorial Sanatorium in River Glade.

27 Several counties in 1918 listed mid-size general hospital facilities. St. Stephen, Sainte-Basile, Moncton, Fredericton, and Campbellton each had a hospital with a 40–50 bed capacity. Woodstock and Newcastle had smaller facilities, with twenty-five and thirty-two beds, respectively. Health care facilities in Saint John were the oldest in the province. The Saint John General Hospital dated back to 1862 while the Provincial Hospital for Nervous Diseases, as mentioned above, dates back to 1847 (Francis). The general hospitals, by contrast, mostly date to around the turn of the century. The two hospitals operated by the Religieuses hospitalières de Saint-Joseph in Sainte-Basil and Campbellton ranked among the older general hospitals. According to directory records, they were founded in 1873 and 1888, respectively. The public general hospitals in the capital city of Fredericton, the Victoria Public General Hospital, was also built in 1888. But the rest of the general hospitals listed seem to be twentieth-century institutions. The general hospitals in St. Stephen and Moncton were built in 1902 and 1904. The remaining two general hospitals, in Woodstock and Newcastle, opened in 1911 and 1916, along with the two hospitals for tuberculosis. The Jordan Memorial Sanatorium opened in 1911 and the Saint John County facility in 1915. Not counting the specialized institutions for chronic diseases, the 442 hospital beds in the province in 1918 grew to 5,096 by 1950, all located in the larger towns and cities of the province (1918 Directory1741–6; 1950 Directory2129–34).

28 The growth of the hospital system in the city of Moncton over this period is instructive. In terms of health care, the city was served by two institutions, the Hôtel-Dieu de l’Assomption and the Moncton General Hospital. The Moncton General grew from a wing of an almshouse in 1898 to a $3 million, 225-bed facility by the 1950s, during a period of growth for the city (MacLellan). Through the interwar period to 1953, Moncton General grew from support from municipal and county coffers, as well as from government or hospital insurance schemes (Godfrey, “Private and Government Funding” 3–34). It was also, increasingly, an institution that required more and more doctors to staff; all eleven of the regular physicians licensed in the city had staff positions on the board, as hospital use was growing dramatically over the first two decades of the twentieth century: “While 458 patients were admitted to the Moncton Hospital in 1910–11, the number grew to 1197 in 1919–20, an increase of over 160 percent that testified to the widespread acceptance and use of hospital facilities” (Godfrey, The Struggle to Serve, 62–63).10 It served all residents of the area until 1922, when the Montreal-based Soeurs de la Providence sent four of their members to found a second, 17-bed Hôtel-Dieu to serve the growing francophone population. The Acadian population in Westmorland County arrived in significant numbers at the turn of the twentieth century (LeBlanc). In 1911, the Acadian population was 28.9% of the total population, and by 1941, the proportion had grown to 33.6% of the population of greater Moncton municipality (Brun 12–13), and this growing population built their communities around a wide variety of French-language institutions, including hospitals. The Hôtel-Dieu was a 125-bed facility when it officially opened in 1928. Local physicians from the Acadian community served on a medical board, organized in 1930 under the direction of Dr. Louis Napoléon Bourque. The hospital continued until an expansion in the 1950s brought their capacity to 188 beds, and in the late 1960s was renamed Hôpital régional Dr-Georges-L.-Dumont in honour of a prominent local physician (Bourque).

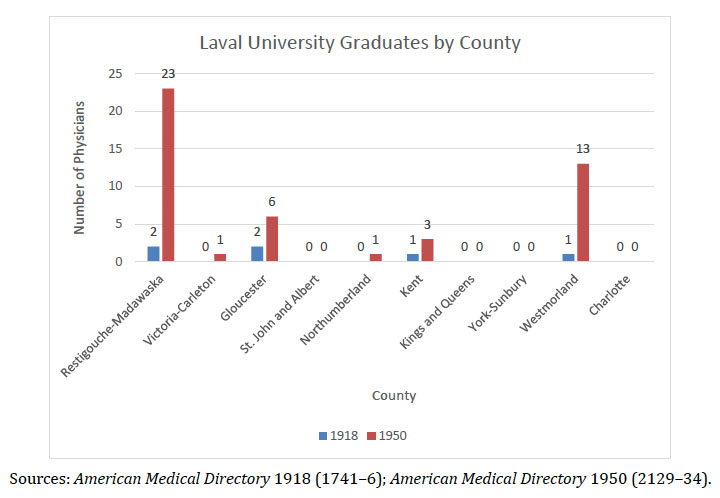

29 How consolidation affected the geographic distribution of physicians is clear, but how it affected physician access is in many ways a tricky question. Certainly, centralization represents a shift from a peripatetic model of medical practice (when doctors went out into the homes of their patients) to a centralized form of service (where the travel burden fell to the general population, who had to go in to clinics and hospitals to receive medical care). This transition, a social transformation in rural medicine especially, was a slow and uneven process. Even in the present twenty-first century moment of this writing, house calls occur, however infrequently. To get a sense of how service centralization influenced physician access, we must try to understand “access” from the patients’ point of view, and delve into local history, memory and the community perspective. But one element with which the directories can assist is in assessing the changing character, training, and, ultimately, the quality of the physicians who, by 1950, represented a new generation of New Brunswick doctors.

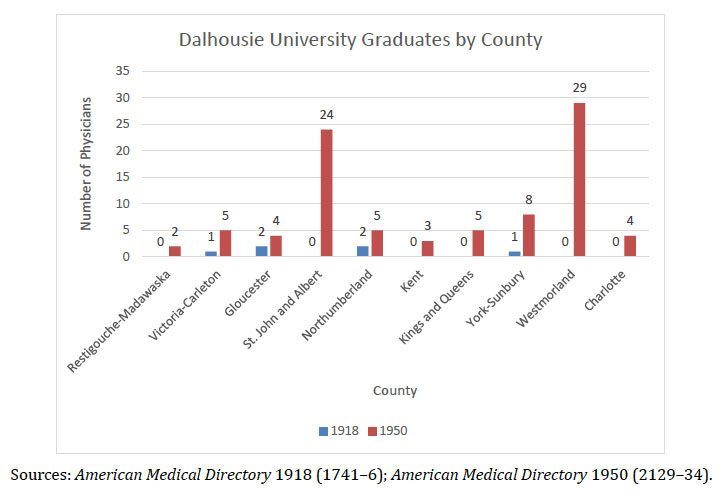

Physician Training and Changing Credentials

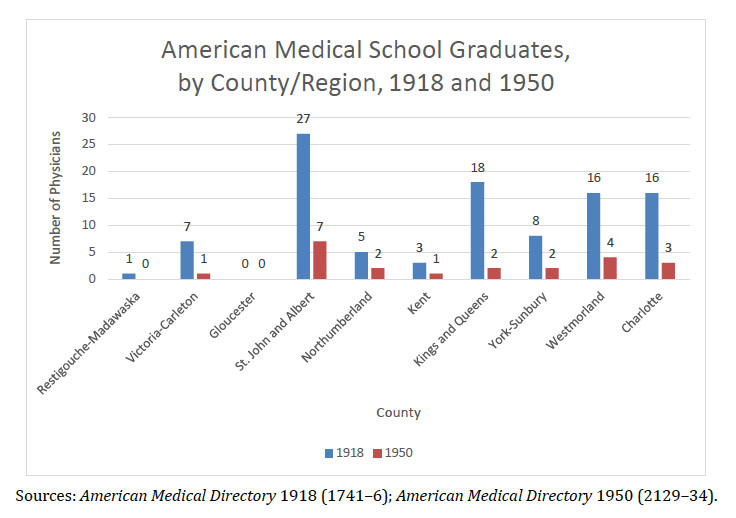

30 In 1918, New Brunswick physicians took radically different career paths depending on whether they were English- or French-speaking. Patients in francophone regions were served by Canadiantrained doctors, while a much higher proportion of physicians in anglophone areas were U.S.-trained. For the most part, and unsurprisingly, physicians in francophone areas of the province were educated in medical schools in Quebec. But not all chose French-language institutions; many studied at McGill University’s medical school. All ten of the physicians scattered over the Acadian Peninsula in Gloucester County in 1918, for instance, received their medical training in Canada: three at McGill, three at Laval, and two at the University of Montreal. The two doctors with anglophone surnames in Bathurst got their training at Dalhousie Faculty of Medicine in Halifax. Of the fifteen physicians in active licensed practice in the counties of Restigouche and Madawaska, only one got their medical degree outside of Canada: Dr. John R. Dishrow of Dalhousie was a graduate of the University of Vermont School of Medicine.

31 For most of the counties with a majority English-speaking population, however, American medical training was far more common. One might expect this for Victoria and Carleton Counties, which are located on the border with the state of Maine. Over one third of the twenty-four physicians listed in border county communities in 1918 held degrees from U.S. medical schools: one from Harvard Medical School, a few from New York (New York University Medical School and Bellevue Hospital Medical College), one from Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine, and one from the “College of Physicians and Surgeons of Baltimore.” Some sought instruction further afield. William D. Rankin of Woodstock, the only doctor in the two counties with surgical credentials, had training from the prestigious University of Edinburgh (Rosner, Medical Education; Reinarz). But throughout Kings and Queens counties, a majority of physicians were U.S.-trained. Eighteen of the twenty-nine physicians registered there were trained in the U.S., including four at Bellevue, three at New York University, four in Pennsylvania (three at Jefferson Medical and one at the Medico-Chirurgical College of Philadelphia), two at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Boston, and another each at Boston University, University of Buffalo, Bowdoin Medical School at Brunswick-Portland, and the University of Oklahoma Medical College. Queens County was also home to one licensed homeopathic physician who was trained at Chicago Homeopathic College. The majority of the Canadian-trained physicians got their degrees at McGill.

32 Does this marked difference in place of medical education tell us anything about the quality of health care? Were anglophone populations in New Brunswick perhaps better served by a more diverse, better-travelled, cosmopolitan medical workforce? The answer is not necessarily. North American medical training was highly variable around the long turn of the twentieth century, although, according to Kenneth Ludmerer and others, the 1870s were a turning point in North American medical education (Ludmerer, Learning to Heal; Rothstein, American Medical Schools). Ambitious physicians had always sought education overseas, particularly at the aforementioned University of Edinburgh (Rosner, “Thistle on the Delaware”). This trend accelerated over the turn of the last century; high-achieving doctors sought additional post-graduate medical training in Europe, including francophone physicians in Paris (Yanacopoulo). These practitioners brought back new ideas for enhancing clinical education through bedside education. The importance of bedside medical education for training doctors on the anatomical-clinical model that underpinned “French empiricism” was widely acknowledged, even though these approaches and practices did not, for most of the nineteenth century, yield dramatically improved patient outcomes (Warner, Against the Spirit of the System; Warner “Remembering Paris”). Around this time there was also an increasing appreciation for the value of incorporating laboratory science into the medical curriculum (Bonner).

33 McGill was a natural choice for medical education because it was one of two Canadian institutions at the forefront of this trend, the other being the University of Toronto. McGill was the oldest faculty of medicine in Canada, dating back to 1829 (Hanaway and Creuss; MacLennan). With a curriculum based on the Edinburgh model, it placed strong emphasis on bedside teaching, a practice introduced by William Osler in the 1880s (Bliss 80–121). In the United States, Harvard Medical School and the newly created Johns Hopkins University also embraced the European trends in “scientization” (Ludmerer, “Reform at Harvard”; Bliss). As Colin Howell and Michael Smith observe, “In the years leading up to World War One,…the authority of the regular profession would increase…as the profession became more committed to disease prevention through the public health movement, as work in the laboratory increasingly demonstrated the virtue of scientific research, and as doctors married notions of personal well-being and degeneracy to the rhetoric of social regeneration and reform” (Howell and Smith 71–72). Laboratory medicine was the key to advancing regular medicine in the wider medical marketplace. Even by the time the First World War drew to a close, most North American medical schools were still engaging in this process of improvement (Ludmerer, “Reform of Medical Education”); it was not until the interwar period that faculty at medical schools became full-time and that most of the top-ranking schools adopted the standard six-year curriculum. This was enabled by a continental ranking and assessment sponsored by the American Medical Association and conducted by education reformer Abraham Flexner, working for the Carnegie Foundation. Flexner visited McGill in 1905 and assigned the school an A rating (Flexner).

34 As the first external accreditation of Canada’s medical schools, the Flexner Report of 1910 generated a lot of interest and anxiety. Against the standard of Johns Hopkins Medical School, Flexner rated McGill and Toronto as excellent; Queen’s and Manitoba as making a creditable effort but requiring more resources; Montreal and Laval as “feeble”—indeed he recommended that only one of these two should be saved to educate French students—and Western and Dalhousie as “poor.” Dalhousie, according to Flexner, was rife with patronage and “laboratory sciences are starved so that dividends may be allocated to generally prosperous practitioners” (Flexner, 326–7). But, as McPhedran and others point out, unlike the many American “proprietary” schools that were closed in the wake of Flexner’s visit, all the Canadian schools surveyed, even those designated proprietary, survived to affiliate with a university and receive a Grade A status by the 1920s (Bonner; McPhedran 12–17).

35 This was not an easy or straightforward process. Medical schools in the U.S., especially regional and smaller schools, continued to operate on the proprietary model well into the twentieth century. A model of education based on didactic teaching, at such institutions modules of clinical knowledge were delivered by clinicians in practice. It was designed to produce physicians for practice, and did not need to incorporate internships because it emerged at a time when apprenticeship with an elder physician was a common “finishing period” before one received a license to practice. These reforms were also not uncontroversial. Various scholars have, since the 1970s, pointed out how this accelerated trends in the centralization of services, to the disadvantage of poor communities and racial minorities; it limited women’s access to medical education by closing female medical colleges (Markowitz and Rosner). Certainly, reforms made medical education more expensive and encouraged the centralization of services, a trend that will be discussed below. Training along these older nineteenth-century models was highly variable, dependent on the quality of the mentor with whom one worked upon graduation. It was possible to graduate from one of the lesser medical colleges and still become a skilled doctor.

36 Nonetheless, the quality of training laid the foundation for future practice, and here we see evidence of a divide. Many of the schools from which anglophone physicians received their medical education also drew stinging critiques from Flexner. Bellevue Hospital Medical College and New York University Medical School claimed the largest number of American-trained New Brunswick physicians in 1918, with sixteen graduates licensed in the province that year.11 Both institutions formally came under the umbrella of New York University, and the growing pains of hospital amalgamation meant that the quality of education received at either institution was good, but not at a competitive level long-term (Flexner 270).12 At Bellevue Medical College, for instance, Flexner reported that “the laboratories are developed unevenly, as the resources of the school are not equal to uniform promotion of all the medical sciences.” And having to compete with the faculty and residents from Cornell and Columbia for clinical time in the Bellevue Hospital proper undermined the bedside training (270). At the time of Flexner’s report, New York University was on uncertain financial footing, and adhered to “a lower admission standard than is scientifically justifiable or educationally necessary” (277). Jefferson Medical College was the third most common medical school among the U.S.-trained cohort, with eight in the province (1918 Directory 1741–6). An independent medical school dating back to the 1820s, it had a solid reputation, even though it was considered a bit of a diploma mill, and sometimes seen as a superfluous institution in a state where medical training could be met by the Universities of Pennsylvania and Pittsburgh medical schools (Flexner).13 And as for the New England diploma mills that some aspiring physicians from English-speaking areas sought out, Flexner did not mince words. With any reasonable reform in medical education, “A thoroughly wretched institution, like the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Boston, would be wiped out,” Flexner wrote, and “the clinical departments of Dartmouth [New Hampshire], Bowdoin [Maine], and the University of Vermont would certainly be lopped off” (Flexner 262). Lopping off these routes to an MD would have cost New Brunswick sixteen resident physicians. Tellingly, none of these schools are represented in the licensed physician roster for 1950, except for a lone graduate of Jefferson in the greater Moncton area.

37 Although all medical societies paid greater attention to accreditation after Flexner, upgrading medical education was tremendously expensive. Over the interwar period, many American schools decided to allow their teaching staff to consult outside of their teaching appointment because they could not pay salaries comparable to their professional income for full-time teaching (Rothstein, American Medical Schools 168–169; American Physicians). Eventually most medical schools lost their independence, formalized their affiliation to a university, upgraded their facilities, and commanded higher fees. This happened in Canada as well. Medical schools at Queen’s, Dalhousie, Manitoba, Montreal, and Toronto “surrendered their autonomy to their university” in return for funding subsidies to offset the costs of curriculum reform, particularly the required investment in laboratory facilities and a full-time teaching faculty (McPhedran 1536). This strategy helped schools survive the years of reform, but in the longer term it could bring challenges if philanthropic or state investment in higher education was cut or compromised, which is just what happened during the Great Depression, when many Canadian universities faced dire straits due to declining enrollments. Dalhousie and Western, for instance, survived only by recruiting medical students from the United States and charging them higher fees. But this all changed with the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1939, medical schools had more applicants than they could accommodate. To support the war effort, the federal government requested that medical classes operate year-round, offering funds to support medical education (McPhedran). This is one reason why a younger, newly trained medical workforce is observable in New Brunswick in 1950. The areas with the most significant improvement in physician health services— Moncton, Campbellton, Edmundston, Saint John, and Fredericton—largely benefitted from an addition of recent graduates who received their training for a medical license in the previous five years. This bode well for these larger towns and cities, but almost two thirds of the medical population who remained in rural areas—like Northumberland and rural areas of Kings and Queens Counties—had medical degrees that were at least twenty years old. By 1950, trouble was brewing for the rural areas of the province where people, regardless of ethnicity, were used to having a resident physician.

38 By 1950, consolidation of training options is also observable in the physician accreditation data for New Brunswick. Not only did the overall number of physicians jump—it more than kept pace with population growth—but Canada became more important in the career training choices of the province’s physicians. The odd physician would still seek training in the nearby state of Maine, where medical education at Bowdoin persisted to 1921 (Keating). But by and large, the medical workforce in New Brunswick “Canadianized” over these decades.

39 Between 1918 and 1950, the jump in number of physicians in francophone regions reflects easier access to French-language medical education. The overall number of physicians in Restigouche and Madawaska jumped to thirty-six licensed doctors, all of whom were trained in Canada, twenty-five at French-language institutions in Quebec. A strong majority (33) received their training in the province of Quebec: twenty-three at Laval, seven at McGill, two at the University of Montreal, and one at Bishop’s Medical College. The others trained at Dalhousie (2) and Queen’s (1). Gloucester County was now home to sixteen physicians, all trained in Canada: six at Laval, four at Dalhousie, three at the University of Montreal, two at Bishop’s, and one at Queen’s. But anglophone areas see the greatest qualitative difference in physician training. Whereas more than half of the doctors in Kings and Queens Counties had training in American schools in 1918, by 1950 sixteen out of the eighteen registered physicians were trained in Canada. Rural areas were equally likely to see this transition as the towns. The two Americantrained physicians in Sussex in 1950 were late-career physicians who received training in Illinois and in Pennsylvania at Jefferson Medical College early in the century. They were now surrounded by mostly newer graduates of McGill (9), Dalhousie (5), and Queen’s (2).

40 The emergence of Dalhousie Medical School as the choice location for medical training for English-speaking physicians is one of the most obvious changes between 1918 and 1950. While McGill remained the dominant institution of the provincial medical elite, English-speaking medical school hopefuls turned away from medical education in the United States to the flagship medical school in the Atlantic region. Although it faced closure after publication of Flexner’s scathing review (Fedunkiw), the school expanded, upgraded, and bounced back thanks in large part to Rockefeller Foundation funding (Ludmerer, Learning to Heal). Social investment on the part of the state and private foundations counted on the success of Dalhousie as a school to train clinicians for the Atlantic region (Reid 64–83). And it seems as though Laval medicine played an equally important role for northern francophone parts of the province. Just as Acadian elites emerged in the late nineteenth century because of economic and political opportunities, the increase of Acadian physicians seems to follow investment in health services and the expansion of possibilities for French-language medical education in nearby Quebec (Andrew). Both appeared to encourage ambitious young Acadians to take up the practice of medicine (Bernier).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5 Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6Preliminary Conclusions

41 A survey of physician registration data for 1918 and 1950 highlights several important features of and changes in the social geography of New Brunswick physicians. First, we see evidence that physician access in New Brunswick was remarkably weak overall compared to national average. Poor physician to population ratios were pronounced in northern and francophone regions in the early twentieth century. Second, the gains in physician access evident by 1950 tend to benefit areas with large towns and cities. Significant disparities in health service access between English- and French-speaking parts of the province began to equalize as many francophone regions experienced an influx of new physicians in the post-war period. Nonetheless, these improvements still did not reach the service levels of southern anglophone regions of the province. Indeed, a service disparity persisted and widened between rural and urban areas, which disproportionately challenged Acadian communities outside of southeastern areas of the province. The border becomes more important in medical education and credentialing. We witness a “Canadianization” of medical education among physicians in the province, as fewer and fewer opt for training in the United States in favour of revitalized programs at home, particularly at Dalhousie University and the University of Laval. While New Brunswick may or may not have had “enough” doctors by 1950, the changes in physician demography signal a significant shift in the “social transformation” of medical practice, a transformation with roots at the community level.

Enabling Further Discussion

42 Community-building efforts between the wars seems to have been organic rather than strategic; they varied according to local circumstance and need, and were intimately tied to the particular struggles and challenges of a particular region. Local circumstance shaped both the institutions themselves and the work of health care providers. Uncovering the local picture through community-based research requires social history methodologies that use sources like biographies, histories of community organizations, hospital records, and community memory captures in various publications. It may also include oral history. It is our hope that adding more qualitative research to this picture over the months to follow will lead us to a better understanding of the health services in New Brunswick over these decades.

43 An interactive discussion hosted by the Journal of New Brunswick Studies is designed to seek out and collect community memory. In this moderated discussion, we will ask for additional details about topics addressed in the article above, including those related to medical credentialing, education, and social distribution. We are also open to questions posed by New Brunswickers who may identify other important areas of health history research. But we begin by posing three research questions as priorities for the crowdfunding project that follows.

Questions

44 Have you other questions related to the evolution of health services in the province? What other questions should we be asking? What sources should we consult?