Interviews

A Conversation with Ann Moyal, Lord Beaverbrook’s Researcher

Ann Moyal is a distinguished Australian historian, whose works on the history of Australian science have included important studies such as Scientists in Nineteenth-Century Australia: A Documentary History (Stanmore, NSW: Cassell, 1976), Clear across Australia: A History of Telecommunications (Melbourne: Nelson, 1984), and Platypus: The Extraordinary Story of How a Curious Creature Baffled the World (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2004). She has published two autobiographical volumes, both of which deal in part with her association with Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, as a writer and research assistant during the 1950s, as well as articles in the Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society (1965) and History Today (2011) that also recall those years. Dr. Moyal, who has held positions at the New South Wales Institute of Technology and Griffith University, as well as with the Australian Dictionary of Biography at the Australian National University, later became the founding president of the Independent Scholars Association of Australia. The conversation that follows is an edited version of an interview conducted by Skype on 28 September 2015 (in Canberra, 29 September). It focuses primarily on her visit to Fredericton and the Miramichi with Beaverbrook in October 1955, and on other aspects of Beaverbrook’s links with New Brunswick and New Brunswickers. Digital files of the original recording may be consulted either at the Saint Mary’s University Archives or the University of New Brunswick Archives and Special Collections. The interviewer and editor is John Reid (Saint Mary’s University).

Ann Moyal, une historienne australienne de grande distinction, a produit des travaux importants sur l’histoire scientifique de l’Australie, notamment : Scientists in Nineteenth-Century Australia: A Documentary History (Stanmore, NSW: Cassell, 1976), Clear across Australia: A History of Telecommunications (Melbourne: Nelson, 1984) et Platypus: The Extraordinary Story of How a Curious Creature Baffled the World (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2004). Elle a également publié deux volumes autobiographiques qui traitent, du moins en partie, de son association avec Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, en tant qu’écrivaine et assistante de recherche pendant les années 1950. De plus, elle a publié quelques articles dans le Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society (1965) et dans History Today (2011) qui s’inspirent de ces années. Mme Moyal a occupé des postes au New South Wales Institute of Technology, à la Griffith University, ainsi qu’au sein du Australian Dictionary of Biography de la Australian National University, et elle est devenue présidente-fondatrice de l’Independent Scholars Association of Australia. La conversation qui suit est une version révisée d’un entretien effectué par Skype le 28 septembre 2015 (le 29 septembre à Canberra). Cet entretien se concentre surtout sur sa visite à Fredericton et à Miramichi en compagnie de Beaverbrook en octobre 1955, ainsi que sur d’autres aspects des liens de Beaverbrook avec le Nouveau-Brunswick et les Néo-Brunswickois. Les fichiers numériques de l’enregistrement original peuvent être consultés aux archives de Saint Mary’s University ou celles de la University of New Brunswick (Archives and Special Collections). L’entretien a été effectué et révisé par John Reid (Saint Mary’s University).

1 John Reid (JR): Could you begin by sketching, for people who may not be familiar with the story, just how you came to be Lord Beaverbrook’s researcher and to be involved with the historical works that he was working on at that time?

2 Ann Moyal (AM): Well, I was very lucky. I had got a first-class honours degree in history from Sydney University and I’d gone off to England on a scholarship and did a little work for a Master’s, but then I was attracted away to work at Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs. I had also put my name down at the British Civil Histories with Sir Keith Hancock. 1 But it so happened that Lord Beaverbrook, who was so eminent as a press proprietor and very powerful for many reasons, had decided at the age of seventy-five that he wanted to become a historian. 2 And for this he’d equipped himself. He’d inherited the Bonar Law Papers because he was Bonar Law’s executor and great friend. He’d also bought, in the fifties, before I joined him, the Lloyd George Papers from the Countess Lloyd George. He’d acquired the Curzon Papers from a lease arrangement, and he had his own very substantial archives. He got his archivist, Sheila Elton—married to the very distinguished Geoffrey Elton, the historian—to go to the British Civil Histories to get a collection of potential research assistants, which did gather a number of people, and I was one of them.

3 I went for an interview and I went for dinner with Lord Beaverbrook and I think I got the job—because it was highly competitive—because, well, I didn’t know anything about him and I wasn’t frightened of him. And I came from Australia and he of course was a Canadian and I suppose that was something, and I was quite pretty and he, there was a certain chemistry, which is always important if you’re going to work with someone. The first question he asked me was about New Brunswick. He asked me—I think I was 26—how should one run a university as a chancellor, and I thought that was quite a challenging question, but I must have ventured into some answer.

4 But I remember contradicting him on a very firm point that he was making on the phone to his editor, about the United Nations, which he hated, and when he came back and sat beside me and said, “What do you think of that?” I said, “I don’t think much of that because the work of the United Nations agencies is so important,” so he got up and went straight back to the phone and said to his editor, “Make a very critical series of paragraphs on the United Nations agencies!” So I knew I would be in for a challenging time. But I was lucky, I was appointed and the work which we were going to do was built on earlier work. He was very important in the First World War. He was a minister, very close to Bonar Law and Lloyd George, and he was a witness of how the politicians went after power in these critical years, and had already written a book called Politicians and the War up to 1916.3 And as he had acquired these wonderful papers which he hadn’t had for the first book, he was going to write about 1916 to 1918, in the book eventually published as Men and Power,4 and it was to be about the battle between the politicians in their quest for power and individual advancement, and the generals. And he took me on as his research assistant. So that was very exciting to me. I was really quite a good research assistant, and experienced by then, and I knew how to stand up to him, and we got on very well.

5 So we began work, and as he said, he had just turned seventy-five and he was going to live as if he was seventeen. And he did, I can safely say, because he never gave up his very dictatorial control of his newspapers, the Daily Express and the Evening Standard, and at the same time we became sort of round the clock working on this very exciting venture, with the help of Sheila Elton, the archivist. Because, to the great horror of the academic historians, he had this rich collection of British national papers and he was not going to let anyone use them until he had finished with them. As he said, he was an old man in a hurry, and they felt that as a newspaperman he was going to rewrite history and it was a disaster and he should never be in that position. They proved quite wrong in the end, as they were ready to acknowledge. But we did work very hard.

6 JR: So could you tell me about the time you went to New Brunswick?

7 AM: I joined him in the middle of 1954 and he at once set me a task to go through all the memoirs that had been written about the First World War, from the participants he was about to write about, and to see whether his account of Politicians and the War was accurate, as it proved to be. I obviously did some good work for him then, because he thought very well of me after that, but I stayed in London and he was always travelling. He had a villa in the south of France, La Capponcina, and then he went to New York and then he went to New Brunswick and then he went to Nassau. He said to me when I got the job, “I’ll tell you, you’ll have to travel.” When he told me the places, like the Bahamas, I must say I practically fell through the floor. But at first, no, when he was away he used his Dictaphone to communicate with me. It was only in September 1955—he always did an autumnal journey to New Brunswick—that we set off on the Queen Elizabeth.

Display large image of Figure 1

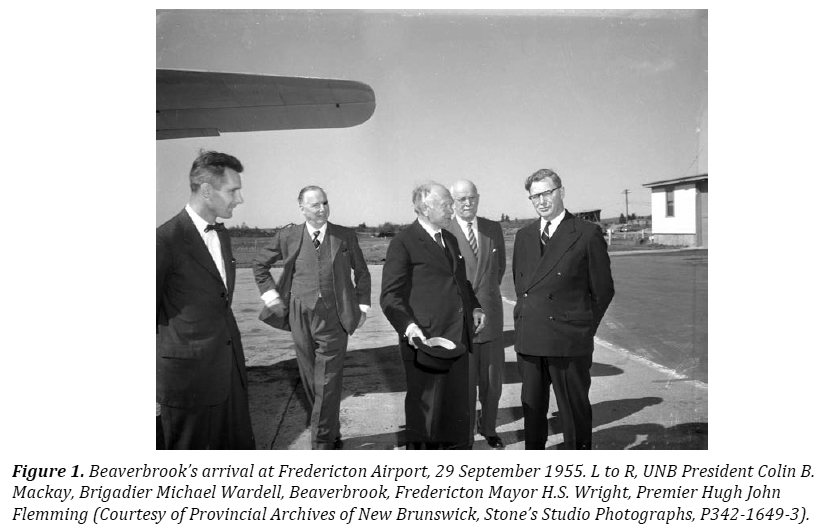

Display large image of Figure 18 We spent a short time in New York,5 and I was dispatched to Yale College, to the library, to look up some important points that we were concerned with in the book we were writing, which became Men and Power. Then I went on to Harvard, and then I joined him in New Brunswick, and that was October 1955.

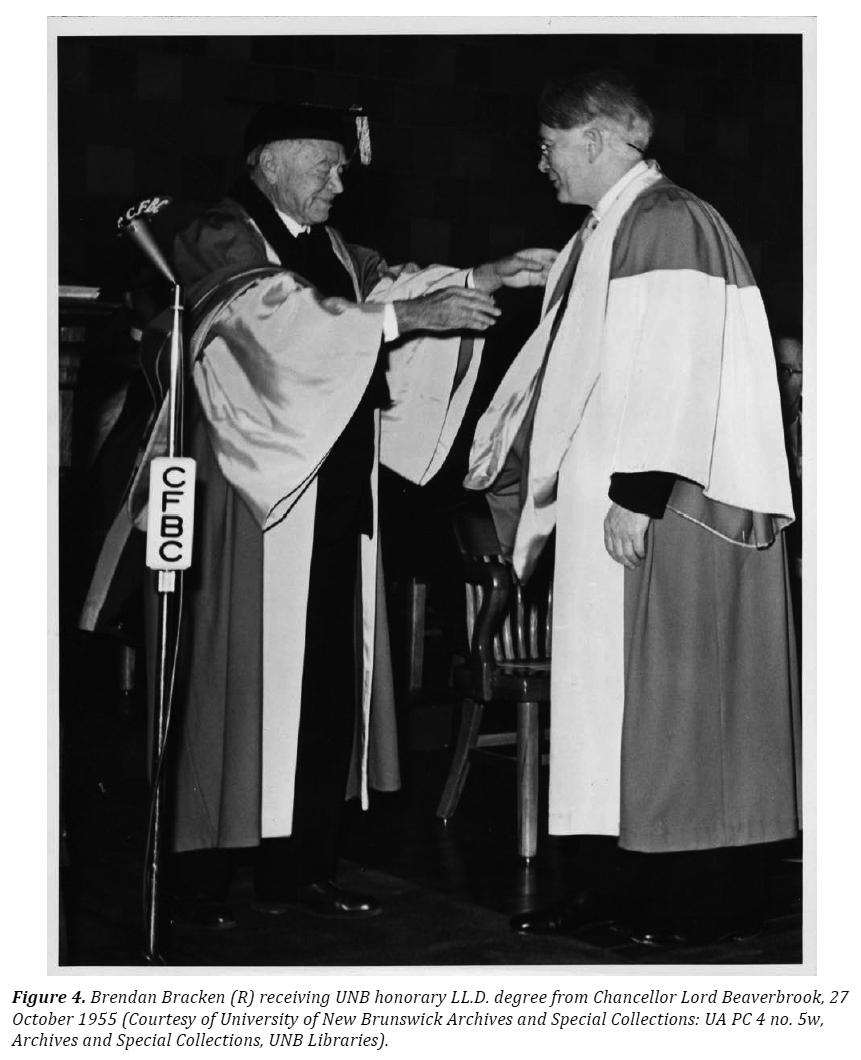

9 I will never forget flying in to the wonderful golden, gleaming orange and red leaves of the fall and then observing what to me was a navy blue river, and that was the St. John. And the light, I mean we have astonishing light in Australia, but the light in that part of Canada was absolutely stunning. And Lord Beaverbrook was then installed, and I joined him, at the president of the university’s house, that is Colin Mackay. Lord Beaverbrook had bought that house and made it a gift to the university.6 As you know there had been quite an outcry when Colin Mackay was appointed president, because though he was a member of that university and a Saint John lawyer, it was an arrangement I think Lord Beaverbrook made with the premier and it was Lord Beaverbrook’s choice, wasn’t it? And therefore the university was disquieted by it, because though he was chancellor he didn’t have the power to do that, and as there was a bit of a hoo-hah about it, Lord Beaverbrook was never one to bow down, and decided that he would resign. So he resigned and then the university was in a terrible state because he was their major donor, and so it was carefully arranged by, I gather, an Act of the provincial legislature that he would be made the chancellor for his life, and they got around their difficulty.7 But what was amusing to me was to arrive at the president’s house and Colin Mackay, who was unmarried and a very nice-looking man, Beaverbrook at once dispatched him out of his own house and sent him to the Lord Beaverbrook Hotel, and there was obviously an empty bed after he’d done that (this was before I arrived) and who was put into that bed but me, a modest research assistant. So it was one of those rather capricious acts which Lord Beaverbrook was given to.8 Then, while I was there, Lord Beaverbrook had invited Viscount Bracken, Brendan Bracken, to come to the university to receive an honorary doctorate of letters, and I was very happy to vacate the bed and go to the hotel and give the bed to Viscount Bracken.9

10 JR: Turning now to your first impressions of Fredericton. You described flying in, and what was your sense of Fredericton as a town when you arrived?

11 AM: Well, it was quite a modest town. One was very conspicuous because Beaverbrook was very anxious to show one around it. He was like a potentate, a visiting potentate, he was the sort of father of the community there and people would come up and address him and of course he loved this. The great thing about being in Fredericton, he didn’t do any writing there, and that meant I was free as a bird—or not as free as a bird, but at least we weren’t locked in many hours of research and writing and so we did a lot of wandering. His secretary was called Jo Rosenberg. She was very attractive, young, she had been with him for some years, she was younger than me but she was very worldly, I would say [laughs], and I learnt a lot from her.

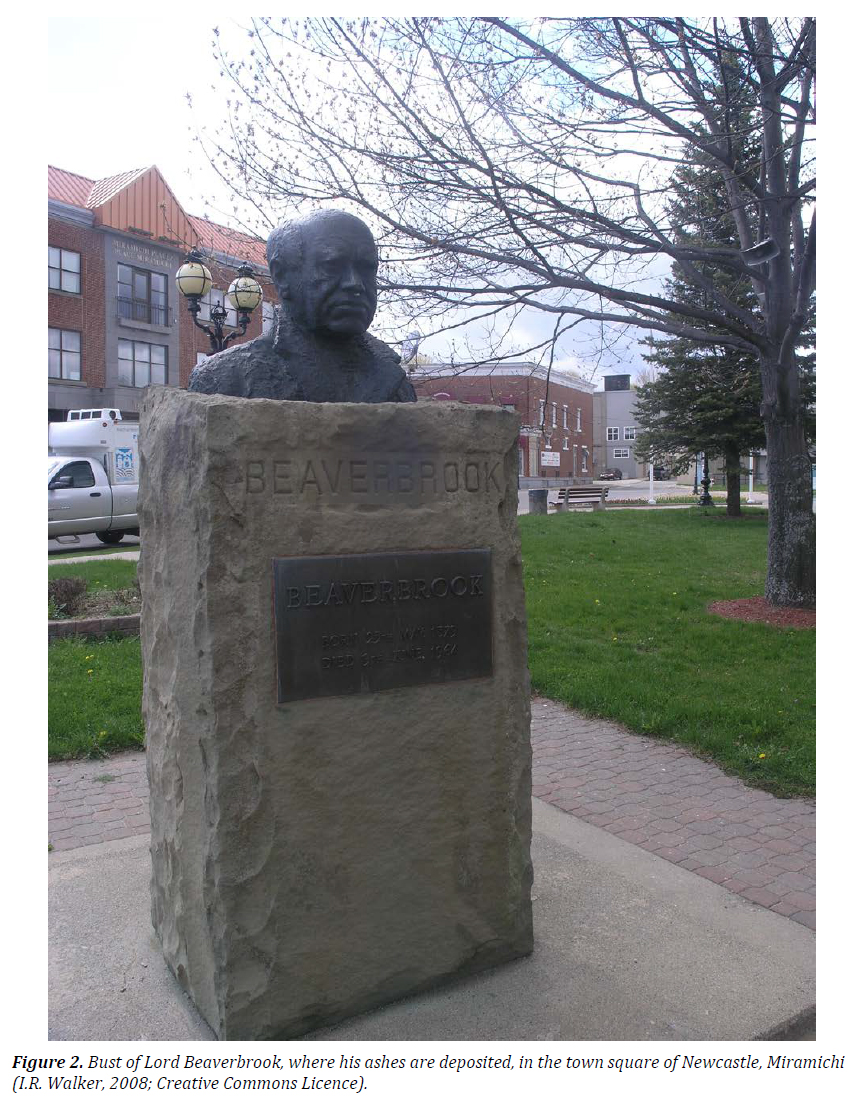

12 We quickly went and visited Newcastle to look at the manse, the Old Manse Library, and his statue, his very fine head, in the square—Oscar Nemon was the sculptor of the head—and Beaverbrook in a gay way said to me, “Of course, they want the corpse,” and of course they got his ashes when he died.10 But in Fredericton there was so much evidence, and he was so proud of the items that bore Lady Beaverbrook’s name, at that time (I don’t know if it’s still the case), I think there was a Lady Beaverbrook Residence for men and there was a Lady Beaverbrook gym. And the bells, the chimes came from somewhere of “The Jones Boys,” the song “The Jones Boys.”11 Where did that come from?

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 213 JR: Well, it’s a Miramichi folk song, and it was Beaverbrook’s favourite song. It went:

They built a mill on the side of the hill

And they worked all night and they worked all day

But they couldn’t make that gosh-darn sawmill pay.

They built a still at the top of the hill

And they worked one night and they worked one day

And Lord how that little old still did pay.

I’ve always thought that it was rather appropriate.12

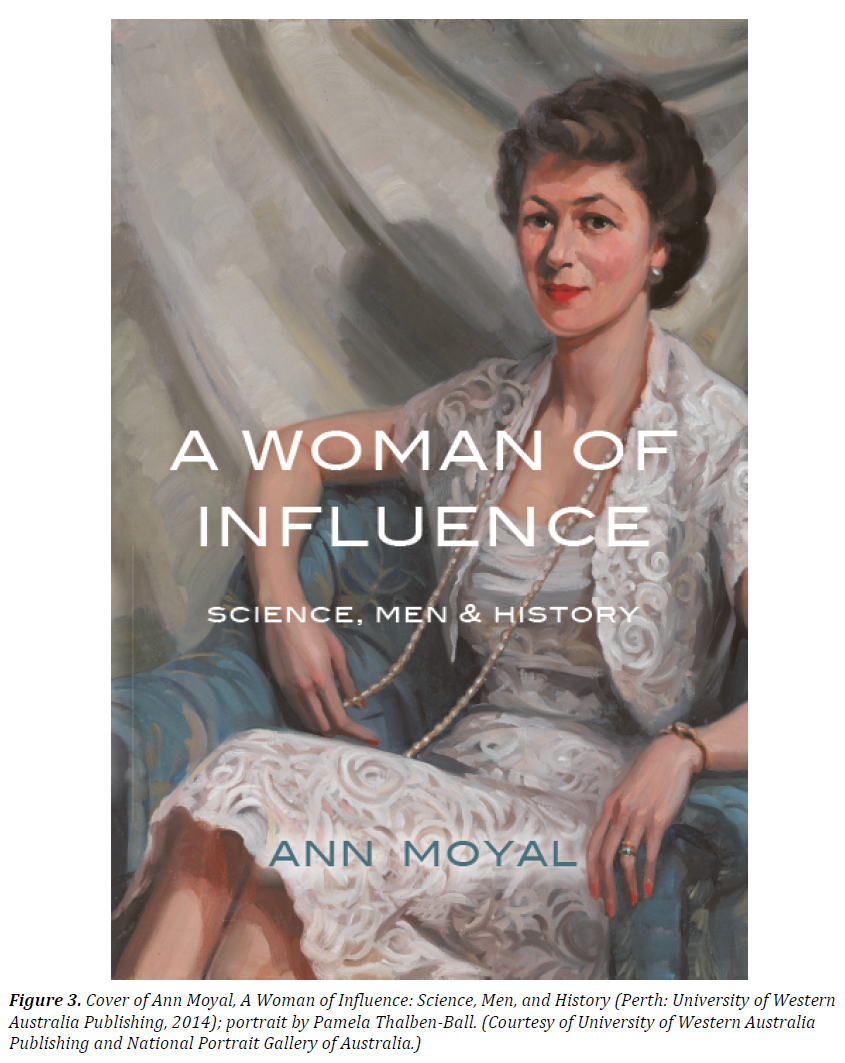

14 AM: Well, a very good message coming out [laughs]. It rolled out of the university in 1955, quite regularly, which was rather strange. I see that its message was clear, and he would like it. But the other important thing that we did in Fredericton, we went to see the library, the Bonar Law-Bennett Library, and of course his devotion to both those men was a conspicuous part of his life. Bonar Law was his pole star politically and in every other way, and he probably overestimated Bonar Law considerably, but before I joined him he had employed a very key historian, Robert Blake—who later became Lord Blake—to write a major biography of Bonar Law, and that was a work of true scholarship.13 He had also employed Frank Owen to write a biography of Lloyd George.14 He was a journalist and that was different. But the Blake biography was very important. And of course there is Lord Beaverbrook himself writing, in his old age, long after I’d left him, the book about Bennett. It’s got a nice title, Friends: Sixty Years of Intimate Personal Relations with Richard Bennett: A Personal Memoir.15 It’s not a book I’m very familiar with, though he sent me all his books when I was back in Australia. But we spent time brooding about the question of the papers because, though he intended to leave the Bonar Law papers at that library, then of course when he decided to become a historian he needed them back and he brought them back to Cherkley.16 But the Richard Bennett ones are there, I believe. Lord Beaverbrook would invite me down to a dinner at Cherkley on a Saturday night, usually with very interesting people attending—that was a great pleasure to me, and it was one reason why he insisted on buying me a dress that I could wear on such occasions because obviously my sort of gowns were not quite up to standard. And there I am on the cover of A Woman of Influence, my second autobiography, and it shows how very posh it was, and that’s what I looked like at that time.

15 The portrait is now in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. But then on Sunday morning we would go for a walk and he would sing hymns and we would go and visit the grave of Richard Bennett.17 So that was a very deep friendship, and that came out very strongly while I was in Fredericton. And I met the key people in his life there. One was Robert Tweedie, Bob Tweedie, and the other one was Brigadier Michael Wardell, who Beaverbrook for his perverse reasons always called “Captain,” I think somewhat [laughs] to the sadness of Wardell.18 He was running the Gleaner, I think, at that time. Well, he was a dashing fellow, but of course he was very much an agent for Beaverbrook.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 316 JR: Yes, could you tell us something about that, about both Tweedie and Wardell, and what you sensed of their roles vis-à-vis Beaverbrook?

17 AM: Well, it’s a bit difficult for me, because I think I was twenty-seven or twenty-eight and not widely experienced at anything, but they were obviously people who danced to his tune, and were very much looking after him when he was there, and certainly he had a lot of correspondence with the Captain, and I see A.J.P. Taylor published various of his letters to Wardell.19 He played a tricky game, Lord Beaverbrook, with everyone I think. I get the impression perhaps that Wardell didn’t particularly plan to find himself consigned entirely to New Brunswick, that he thought perhaps this was going to be a shared activity, the Gleaner, but he was left with the whole responsibility for that.20 But Bob Tweedie, he again was a very nice man. They were both extremely nice to me, in fact I think it was Bob Tweedie who took me on a motor journey to see the country around, which was very beautiful at that time. And again I don’t really have any light to shed on what he did for Beaverbrook, but he was related to a former premier.21

18 And for the rest, the circle that I was exposed to included Lady Jean Campbell, Lord Beaverbrook’s granddaughter, who was with us at the time. She took rather a fancy to Colin Mackay, and Lord Beaverbrook in his well-known way—we were all to fly on to Toronto, and she thought she was going too because Colin Mackay was also flying to Toronto.22 But she found herself left on the tarmac, frustrated—the sort of thing he liked to do. I will always remember Fredericton, because there was a warmth and, there was, well, there was a sort of suburban air about it. I came from Sydney, I wasn’t very sophisticated then, and they were very friendly. I remember Lady Jean Campbell because she and the secretary, Jo Rosenberg, at that time we were invited to go to a square dance, and we went square dancing in New Brunswick. But it was the beauty of the place, the fall, and that wonderful river, which we used to walk along, because I had never seen a river that colour, and it’s remained stamped in my memory. And it’s a very long time ago, casting back to 1955, but there it is, as sharp as the day. Rich and golden, and the river—very lucky to have that combination.

19 JR: Did you meet Premier Hugh John Flemming?

20 AM: No. He wasn’t at the dinner table. I mean one of the nice things when you were travelling, at least you were invited to the events, and I well remember the dinner when Brendan Bracken, who had as I knew at the time, he’d spent five years of his early life in Australia, he’d been expelled by his mother from his Irish home because he was a rebel and he was sent out to Australia. He was assigned to a pastoral estate there just on the edge of the Murray River, but he made a lot of progress while he was in Australia, because again entrepreneurially he was a tricky fellow. When he got back to England he was able to persuade someone to let him go to one of the major public schools, and rose and finally became Churchill’s private secretary. It was his advice, I later learned, to Churchill in 1940, when Chamberlain called Lord Halifax and Churchill together, when he was about to retire, that Bracken had advised Churchill when the question was set, who should take the role, he was to remain silent. This wasn’t very characteristic, but Churchill remained silent, and Halifax therefore was forced into saying that perhaps Churchill was the man, whereas if Churchill had leapt in it might have been a different sense.23

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 421 So I’ve always thought well of Bracken. Bracken was a very voluble fellow, talking at the dinner table, and I notice in my autobiography, Breakfast with Beaverbrook, that I say that Mr. Tweedie and “Captain” Wardell—they came well done with Brylcreem and nicely suited, but they were dominated by this very sophisticated figure from England.24 But they were very nice to me. It was the time when perhaps Lord Beaverbrook was his most relaxed in the whole time that I was with him, because he adored his role there, and he was such a generous chancellor. I read somewhere that he probably gave something amounting to £10 million to New Brunswick across his career, and when at the age of 75, which is when I met him, he gave up being a shareholder of the Beaverbrook papers, and the Beaverbrook Foundation was created, a tremendous amount of that went to scholarships for people to come from New Brunswick to London and vice versa, so he was very much a father to the province in his generosity.25 And it’s hard to know how well he’s remembered there, because in the course of this conversation I would just like to emphasize how very important he became as a historian. I don’t know if that’s much known about in Canada.

22 JR: Possibly not, and I think also the memory of Lord Beaverbrook probably has faded over time and perhaps has been influenced for many New Brunswickers by the disputes over the art gallery that became extremely well known publicly, and have tended to some degree to overshadow the earlier phases of Beaverbrook’s relationship with New Brunswick.26

23 AM: At that time he had an art advisor who had been with him some months by the time we were in New Brunswick, called Le Roux Smith Le Roux, he was a South African. He’d been an art assistant at the Tate, so he was qualified. He was acting as the agent for Beaverbrook in considering this whole question of the art gallery and making lists, because Beaverbrook I remember in his apartment at Arlington House in London, had a very beautiful Fragonard and he had a Turner. I think they might have been shifted quite early, because when we were there in October 1955 there was no art gallery then, it was all focused on the library, and there was a showing when I was there.27 But Le Roux was a very odd man, he and Beaverbrook pretty soon fell out,28 and after that I saw catalogues, and when I came back to Australia, having left Lord Beaverbrook, he used to send me catalogues and I know that Churchill’s lovely painting of La Capponcina ended up in the gallery. I don’t think Beaverbrook knew a great deal about art, certainly in those early stages. He had employed a woman called Madame Escarra, who had left soon after I was appointed to the staff, to teach him French.29 I don’t think he ever learned a word of French [laughs]. She at times would go for walks with him in Green Park, and so she persuaded him to occasionally go and look at an art gallery, and I think that was his early training. I think he was very much the sort of man who knew what he wanted, and he very much liked Graham Sutherland, for example, and of course Graham Sutherland painted that wonderful portrait of Lord Beaverbrook in his purple suit and his brown shoes, and it has eventually ended up at the gallery. Sutherland also painted the portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, which Churchill’s wife destroyed. She loathed it. But I know Beaverbrook had wanted that for the gallery.30

24 JR: So Beaverbrook had wanted the Churchill portrait?

25 AM: Yes.

26 JR: For the gallery in New Brunswick.

27 AM: Yes. But it was surreptitiously destroyed. He did put an awful lot of marvellous paintings into the early gallery. I vaguely followed the later debate, but we didn’t hear much of it in Australia. Is it called the Beaverbrook Art Gallery now?

28 JR: Yes.

29 AM: So at least his name is perpetuated.

30 JR: Very much so.

31 AM: But, I notice this myself, if you mention Lord Beaverbrook’s name to anyone who isn’t somewhere around my own age, in Australia, there are not many people who know or remember now. When I joined Lord Beaverbrook, as I say, I didn’t know much about him, but he had five careers, of which his career as a historian was the fifth, and certainly in his old age, when he approached death, he wanted to be remembered for his books. I have felt it’s been, well, it’s very much part of my career to write about him as a historian, because he was a phenomenon in a way. He was a man with a most extraordinary memory and a tremendous curiosity about people, and this combination left him with a singular remembrance of the politicians during the First World War, all very significant figures, you know— Lord Curzon, and Carson, and Churchill of course, Bonar Law, Lloyd George—and he was instrumental in helping to bring Asquith down as prime minister. He was much hated by a lot of people. I, of course, adored him. He was charismatic, and of course I was connected with him in the thing that was his greatest interest for several years at that time, so I was very privileged. But it was so pertinent, his memory was so pertinent, in the historical work, to having access to these papers, which were splendidly catalogued by Sheila Elton.

32 The history that Beaverbrook, with his knowledge of the personalities and the stratagems of the time, was able to bring together was very different than, say, Lloyd George’s record of the events dealt with in Men and Power, which was fuzzy and quite different. And as a result, when Men and Power came out, it put Lord Beaverbrook as a historian on the international map. And the ivory tower praised that book highly, it went into numerous editions. I’m very proud that I was associated with it, because the way we worked was quite singular. He had, as I said, this tremendous recollection of people, and his curiosity about their motives, and he had this racy way of talking about that. We would go for a walk in Green Park, outside his apartment, and he would tell me the story of what would become a chapter, and I would then race off to my office—for a while it was at the Daily Express and later I moved it to his apartment and worked there—and then I’d write it up and I would then give him the draft, and of course he’d read it overnight and then it would stimulate him to further recollections, and then Sheila Elton would be asked to bring up the relevant papers, and I’d redraft the chapter. In this way I’ve always believed that even the most talented historian today could never write of that period and that particular battle between the generals and the politicians who were fighting for power during the critical years of war—they could never have told the story as it really was, only a Beaverbrook could do that, with his memory and his determination and his access to the documents.

33 And there were many stormy scenes when Mrs. Elton would not be able to find something he knew would be in the papers, and as one journalist said of Lord Beaverbrook, working for him, “Some days it was Christmas, and some days the Day of Judgment.” We would have quite a bad time, but he was always right, which is the whole point, so that as a historian, everyone now—even Martin Gilbert, the historian of Churchill who’s written so much—says that Lord Beaverbrook’s writing of the history of the First World War has changed our picture of it. He may not always be absolutely accurate, he has a tendency perhaps to emphasize his own role, but it’s unique and that of course was what Lord Blake said of Men and Power, that it was the combination of documents and memory—because his first books hadn’t had that access to the papers.31

34 JR: Could I take you back perhaps to Beaverbrook as the chancellor of UNB. You’ve mentioned how he would arrange honorary degrees for some very prominent people. What was his approach to being chancellor?

35 AM: Well, I think he was interventionist certainly, as shown with the appointment of the president. I really don’t know enough about his affairs, but he obviously did feel a deep sense of ownership, and I think that it was one of the things that perhaps meant more to him than an awful lot of other things. I mean, power he had and influence he had, much hatred and envy he had, and had lost a great deal of affection from people who worked with him, but this was a very special role in his life, I think. After all, he didn’t have a degree of any kind himself, and in a way he suffered from that. I noted that particularly after Men and Power was published. When we were writing Men and Power, there was a tentativeness. He didn’t have the total confidence of a scholar, and I suppose in a way, because I was a good research assistant and I can write, he became very dependent on my writing. He had a certain respect for the ivory tower and academics, and he wasn’t totally confident of his role because he’d had a lot of ammunition fired at him over the ownership of the papers. So I noticed the difference after the success of Men and Power, which had enormous success, tremendous coverage of course, and a lot of very, very fine reviews.32 When the book was published I had, I regret to say, married again briefly and that did not please Lord Beaverbrook, so for several months I was rapidly sent away from my job, but he did lure me back and finally I spent this wonderful time with him at La Capponcina in the south of France when he had Churchill staying with him, and I claim to be the only Australian who has spent a month solidly in the same house as Churchill, and what an experience it was.33 But when I sat down with him in the south of France, he was then going to finish writing the book he had started a long time before, on the abdication of Edward VIII, and instead of my being the initiator of how we were going to approach it, I was just sitting there sort of looking on, he was doing it.34 He had a totally new confidence after that, and of course he did go on to write many books. The most important on the history front was The Decline and Fall of Lloyd George, but he also wrote the one on the collection of letters of Richard Bennett, and he wrote about Sir James Dunn.35 I never met Sir James Dunn, nor did I ever meet Christofor, whom Beaverbrook later married.36 By the time in 1958 I was with him, I had decided to come back to Australia. But why I claim his special significance as a twentieth-century phenomenon is that (1) he was a proprietor who bought the papers, the really important papers, and (2) commissioned works—Lord Blake and Owen—and (3) wrote the highly definitive book on the First World War, on which he now remains a source in the political history arena. So that in a way he was a historical oneoff, the combination of this archivist, and patron or commissioner, and writer. It’s a singular story and, in a sense, though Churchill had an enormous amount of help for all his work, Beaverbrook certainly had help, but not anywhere like that kind of help. And I don’t want him to be forgotten, because he wanted to be remembered for his books.

36 JR: Among the people in whom Beaverbrook took exceptional interest in terms of his writing and his research, a surprisingly high proportion of them are New Brunswickers—Bonar Law, Bennett, Sir James Dunn. What does this tell us about Beaverbrook and his sense of belonging to New Brunswick? Does it tell us something about that?

37 AM: Yes, of course it does. I mean the fact he knew Bennett when he was nine years old, and he loved Bonar Law. Beaverbrook was an immigrant, was a Canadian immigrating, although he pumped lots of money into England and miraculously fell under the friendship and concert with Bonar Law, which contributed to his political rise. It was a very early rise, he gets there in 1910 and only about a year later he gets a knighthood. It’s never quite clear why he got a knighthood, but then of course he becomes dedicated to Bonar Law and to his progress.

38 JR: And both he and Bonar Law were sons of the manse, which I wanted to explore a little bit with you. You mentioned walking with Beaverbrook in the grounds of Cherkley and he would sing hymns, and when you visit Newcastle, of course the Old Manse is one of the central places that’s associated with him. But how much, or to what degree, would that—being a son of the Presbyterian manse—be a key to certain aspects of his background?

39 AM: Well, his frugality. He was terribly frugal when we travelled [laughs]. His valet, Raymond, who was a character in his own right, was always darning his socks—frugality was practised in an extraordinary way.37 And he was tremendously knowledgeable about the Bible, he knew the Bible backwards.38 But he was a mix of a character, because the curious thing was that though he was a man who was very interested in women, I was very struck when I first went to Cherkley to see that when you sat down in the dining room you looked out a window and you saw a cross—it was a cross to his wife, his first wife, Gladys. That seemed to me quite a mysterious thing, though I notice in his book he wrote about My Early Life, he describes at some length how he found her as a young woman quite unworldly.39 I think he was very young, and married her, and she was important as a first wife, but she didn’t loom very large in the whole account of his life. But it was a bit like what you’re saying about New Brunswick and his beginnings. It was far more important to him than one might have known. Balfour called him “the little Canadian adventurer,” and that clung to him for a very long time, and there’s no doubt that he was, and of course he had a very Canadian tone of voice, and yet one didn’t really think of him particularly as a Canadian.

40 JR: Is there anything else that we haven’t covered that might be significant?

41 AM: I think that his association with New Brunswick was revealing in many aspects. It was revealing in the way he moved men around and had them at his disposal—and Bob Tweedie and the Captain were very much of that kind. He had a great generosity and kindness to a lot of people. He was essentially a foul-weather friend, and that comes out in his relationships with so many people. He was really quite a foul-weather friend to me in some ways. But it was a conspicuous feature, there was a great kindness in him but there was a lot of capriciousness and, you know, he was tricky. Sir Keith Hancock always described Lord Beaverbrook as an evil man, so there was always a strain of people who couldn’t stand him, although I think that Sir Keith was happy to take me on as his assistant at the Australian Dictionary of Biography because I had worked for Beaverbrook. But there’s no doubt that he was a phenomenon, and this is what I emphasize, I mean the books he wrote after I left, I often wondered if I had stayed with him if he might not have accomplished the ones he planned. He planned another work on the period of Stanley Baldwin, a man he particularly despised, and then a major work on Churchill and the war. And the regret is that those books never happened, and the books he wrote on Dunn and Bennett—which I understand why he wrote them, because once you’ve become a writer you want to go on writing —were less important than his other books. And in the end, in his last year he wrote the last book, My Early Life, and that was published after his death, and is just ordinary. Certainly, he has a long list of books that I haven’t mentioned, but I know the best of them—Men and Power. That’s what I know [laughs]. And I hope he’s remembered for it.

42 JR: Thank you.

Appendix: Historical Works by Max Aitken, Baron Beaverbrook

- Lord Beaverbrook. Canada in Flanders. 2 vols. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1916–17.

- ---. Politicians and the War, 1914–1916. 2 vols. London: Thornton Butterworth, 1928–32.

- ---. Men and Power, 1917–1918. London: Hutchinson, 1956.

- ---. Friends: Sixty Years of Intimate Personal Relations with Richard Bennett: A Personal Memoir with an Appendix of Letters. London: Heinemann, 1959.

- ---. Politicians and the War, 1914–1916. 2nd ed. London: Oldbourne Book Co., 1960.

- ---. Courage: The Story of Sir James Dunn. Fredericton: Brunswick Press, 1961.

- ---. The Decline and Fall of Lloyd George: And Great was the Fall Thereof. London: Collins, 1963.

- ---. My Early Life. Fredericton: Brunswick Press, 1965.

- ---. The Abdication of King Edward VIII. Ed. A.J.P. Taylor. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1966.