Articles

Place-Conscious Pedagogy and Sackville, New Brunswick, as a Learning Community

Abstract

There is growing support for the value of place-conscious pedagogy at the undergraduate level. It has found momentum in arguments that suggest regular interactions with one’s surroundings allow for knowledge to be practised while being learned. This case study investigates the delivery of Place Matters, a week-long intensive program delivered in Atlantic Canada, at Mount Allison University, that attempts to develop students’ sense of place within the university and surrounding community. Grounded in value-belief-norm (VBN) theory and the new ecological paradigm (NEP), this mixed-methods study employs questionnaires, post-program interviews, and direct observation methods. This study attempts to discover whether it is possible for students to significantly develop their sense of place during the course, to what extent students’ value and understand their sense of place, and how their developed sense of place has altered their understanding of the human relationship with the environment. It additionally proposes a link between sense of place and VBN theory, which leads to a further theoretical connection between place and the NEP.

Résumé

Il existe un appui de plus en plus manifeste quant à l’importance d’une pédagogie visant à développer le sentiment d’appartenance au niveau du premier cycle. Cette pédagogie a connu un nouvel essor dans les arguments qui donnent à penser que des interactions régulières entre une personne et son milieu favorisent l’apprentissage et la mise en pratique des connaissances. La présente étude de cas analyse la prestation de Place Matters, programme intensif d’une semaine offert au Canada atlantique, à la Mount Allison University, qui vise à développer chez les étudiants un sentiment d’appartenance au sein de l’université et de la collectivité environnante. Fondée sur la théorie « valeurcroyance-norme » et le « nouveau paradigme écologique », l’étude à méthodologie mixte emploie des questionnaires, des entrevues après programme et des méthodes d’observation directe. Elle vise à voir s’il est possible pour les étudiants de développer un sentiment d’appartenance de manière significative pendant la formation, de voir dans quelle mesure ils apprécient et comprennent leur sentiment d’appartenance et de quelle façon leur sentiment d’appartenance a changé leur compréhension de la relation humaine avec l’environnement. En outre, l’étude propose un rapport entre le sentiment d’appartenance et la théorie « valeur-croyance-norme », ce qui mène à un autre lien théorique entre l’environnement et le « nouveau paradigme écologique ».

Introduction

1 Is the increasing emphasis in higher education on producing internationally focused graduates reducing the opportunities for undergraduates to learn from the local? Proponents of place-conscious pedagogy such as David Greenwood1 and Wendell Berry answer yes and have argued for the need to enrich students’ sense of place during their undergraduate education. This study analyzes the effects of Place Matters, a course designed to develop students’ sense of place, on undergraduate students at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada. Place is the emotional and personal reflections and meaning imposed on space; it varies from person to person and from location to location. Everybody has a sense of place, wherever they are, be it in their hometown, a school, church, or living room. However, people may develop a stronger sense of place by interacting with and learning about the space around them.

2 Place-conscious pedagogy is a growing branch of educational research that aims to shift educational systems away from standardized and unengaging teaching practices toward place-based education that promotes awareness of place by drawing connections between the local context and what is being taught. The pioneering research of Wendell Berry and David Greenwood on place-conscious pedagogy has been expanded by many authors, including Somerville, Ball and Lai, and Perrone et al. They share a belief that place-conscious pedagogy provides wider social, educational, and environmental benefits than current conventional practices in higher education.

3 This study fills a gap in the literature by providing a case study of a course, delivered in 2013, that was specifically designed to improve undergraduate students’ sense of place. The aim is to examine the potential benefits and limitations of place-based education. This study assesses the effects of student participation in a course focused on place-conscious learning. Although the study is limited to a single course, it provides a specific example of the implementation of place-based education at the undergraduate level. Furthermore, it connects place-based learning to environmental action.

4 In the absence of a generally accepted evaluative process for place-based learning initiatives, this study uses a qualitative approach to understand the effects of participation in the course on students. It explores how students perceive changes in their sense of place after participating in this one-week course, and whether these changes have any implications for the students and the field. It explores the link between place and personal values by exploring the relationship between sense of place and the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory developed by Stern, Dietz, Abel, Guagnano, and Kalof. Interviews with students and observations recorded during the course provide additional insight into how a sense of place is shaped from the student perspective.

The Course

5 This study focuses on the experience of students enrolled in a course designed to increase their sense of place through interactions with various individuals, locations, and themes in the space around them. Entitled Place Matters, the course is a week-long, intensive, full-credit course.

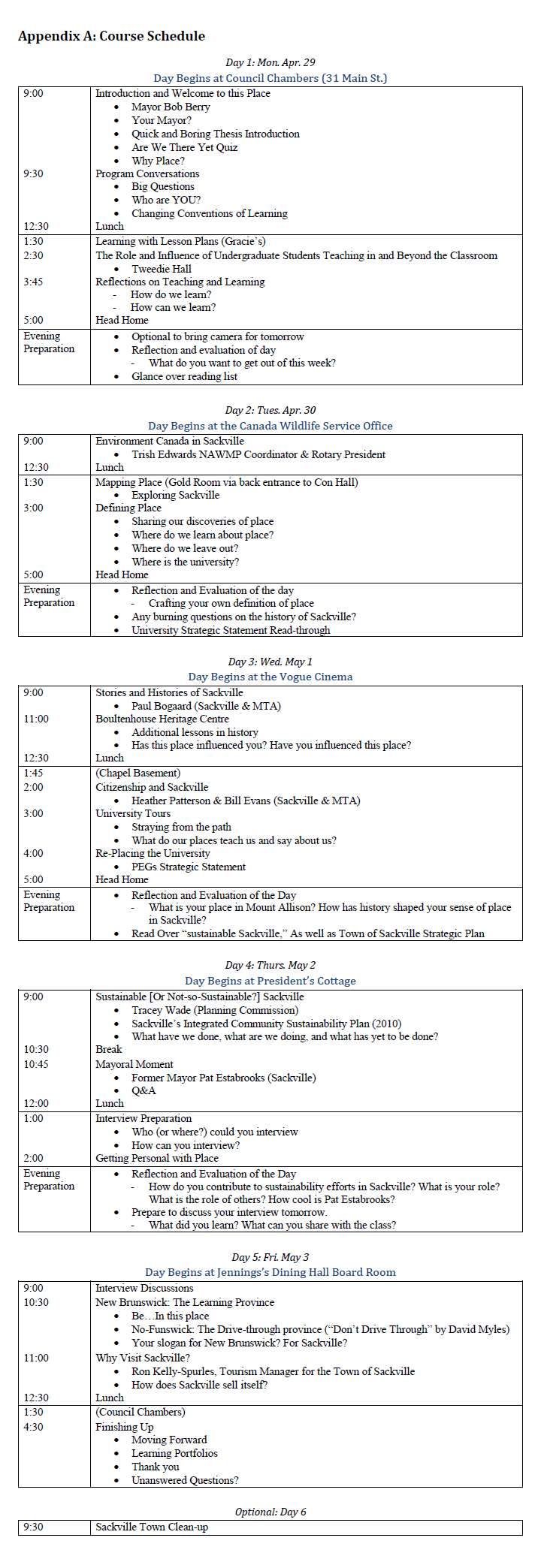

6 The primary objective of this course is for students to develop the skills to improve their sense of place within a community, using Sackville, New Brunswick, as a focus. During the week, students learn how their existence within the university and town might benefit the wider community. They engage in sessions facilitated by the instructors, the students, and by members of the community, including a representative from the Canadian Wildlife Service, a former mayor, and employees of the university. Students participate in discussions focused on learning strategies, hear from local historians, interview local residents, and explore the geographic area through creative lenses. As detailed in Appendix A, the students engage with the subject matter over the course of the week; then they develop their own independent learning portfolio in the following months. Each student designs a portfolio in consultation with the course instructors; these portfolios can include journals, interviews, essays, project ideas, or a plan to implement a project within the community. The purpose of these portfolios is to allow each student to describe their individual exploration of place. Topics include the relationship between the town and the university; a comparison with student sense of place in Kingston, Ontario; the role of sport in the community; and the natural environment.

Research Questions

The research questions for this study are as follows:

- How do students enrolled in the Place Matters course understand or experience place?

- What factors do students think help connect them to place?

- To what extent can a week-long intensive course effectively change undergraduate students’ perception of place?

7 These research questions address the study’s three goals. First, the study focuses on some of the potential benefits and shortcomings of place-conscious pedagogy. Second, it analyzes the way this specific course was actually delivered. Intensive courses such as Place Matters, which are delivered in just one week, are not suitable for all subject matters. It is important to determine if the length, setting, and style of the course allow the students to gain a confident understanding of the subject matter. Lastly, the study experiments with an alternative method of evaluating this style of learning. A strategy for easily measuring and comparing data measuring the benefits of place-conscious learning is absent from the literature.

Theoretical Background

Place

8 According to David Greenwood, place is a reflection of the human experience on a location and is a human perception that both teaches and defines us (Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”). It is a combination of the physical characteristics of a location and the personal and human connections that we make to it. Place is not defined by size, and can encompass a chair in a living room or an entire city. Greenwood (Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”) and de Carteret have shown that there is a symbiotic relationship between individuals and space: people make places and places help to make people. Through place, we express culture, and a place is shaped by the decisions, actions, and understandings we have of the world around us: “Place provides a local focus for sociological experience and inquiry” (Greenwood 94). Places are relevant to people’s everyday lives and therefore represent strong learning environments. To really know place is to “understand how the environment, culture, and politics have worked to shape it” (Greenwood 94).

Values

9 Based on their review of the literature on value theory, Schwartz and Bilsky define values as “concepts or beliefs, about desirable behaviours that transcend specific situations, guide selection or evaluation of behaviour and events, and are ordered by relative importance” (551). Hitlin and Piliavin show that values are developed through social interactions and usually only change slowly, if at all. Other studies have examined how values provide the foundation and guidance on which behaviour is based (Stern, Dietz, Abel, Guagnano, and Kalof).

Place-Based Education

10 Place-based education is an educational strategy that seeks to enrich the learning experience for students, instructors, and others by teaching academic subjects while simultaneously developing students’ sense of place. It is a multidisciplinary approach, with content designed around the geography, ecology, sociology, and politics of a place (Woodhouse and Knapp). It is a combination of natural history, which allows people to connect to non-human aspects of their lives; cultural journalism, which expands people’s sense of community by connecting them to each other; and action research, which is the practice of examining what is around you, identifying problems, and discussing solutions (Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”).

11 This study makes a distinction between place-based education and place-conscious pedagogy. Place-based education is concerned with methods, whereas place-conscious pedagogy is a philosophical and political orientation within the field of education. In “A Critical Theory of Place-Conscious Education,” Greenwood explains that place-based education is nearly synonymous with community-based learning; both provide students and educators with opportunities to interact with the community in order to enrich the student experience and increase student engagement. Place-based education, a framework for the future of contemporary education models, is the dominant tool through which place-conscious pedagogy is promoted in the educational system. This study assesses the merits of place-conscious pedagogy by assessing the outcomes of a place-based education course, Place Matters. Throughout this paper, the terms place-conscious learning and place-conscious pedagogy are used synonymously, but they are distinguished from place-based education. Place-conscious pedagogy is the overarching theory, whereas place-based education consists of the tools and methods used to implement the theory.

12 Place-based education emphasizes connecting students and teachers through experience, reflection, and engagement in the local area, specifically the area’s cultural and ecological components (Gruenewald “Accountability and Collaboration”). Currently, lessons at the undergraduate level are not rooted in familiarity, which means that they are not being practised while being learned. In fact, David Greenwood argues that contemporary schooling at all levels does not sufficiently address the concept of place (Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”). Universities provide students with a career-oriented and streamlined education, while place-based education seeks to improve students’ ability to connect their education to the real world. Universities can play an active role in helping students develop a sense of place during their undergraduate degree by incorporating place-consciousness into the curriculum.

13 Efforts can be made to reclaim a sense of place at the undergraduate level. Current education systems, with their disregard of place, have made us think that the world is really disconnected (Orr). While no medium or topic will ensure that students are prepared to immediately address major global issues, Stables argues that education can be designed to help students to consider their place within the world and the ways in which humans are intertwined with their natural environments.

14 Ball and Lai have documented the early attempts to reform education around the social and ecological well-being of place in the last third of the twentieth century. Based on their own work, they argue for the need to develop educational experiences contingent on place, an idea they acknowledge is contradictory to the standardization currently spreading across the international higher education system. Despite this trend toward standardization, by 2010, Somerville was able to identify two approaches to place-based education in the literature. The first is Berry’s ecohumanist approach; a liberal, humanist approach that accuses universities and academics of ignoring the environmental sensitivity of the planet. The second approach, as outlined by Somerville, was pioneered and developed by Greenwood, who more explicitly references the concept of place and is more critical of the university’s failure to connect students to their surroundings. This approach focuses on environmental behaviours, while encompassing social factors and, to an extent, economic factors.

15 Few tangible examples and models have arisen to suggest how place-based education may be implemented in universities. Theobald, in his 1997 book, presents a linear model: interested people are brought together, ideas are developed and applied, schools are reformed, and the relationship between students and their community is reformed. This model is perhaps too simple and too vague to be adopted as an effective strategy. Theobald’s model, in an effort to be generalizable, lacks sufficient detail and consequently is difficult to apply within the diverse higher education system. What has become clear from preliminary research of place-based education is that while there has been substantial theoretical development, there have been limited practical applications or assessments of its merits within higher education.

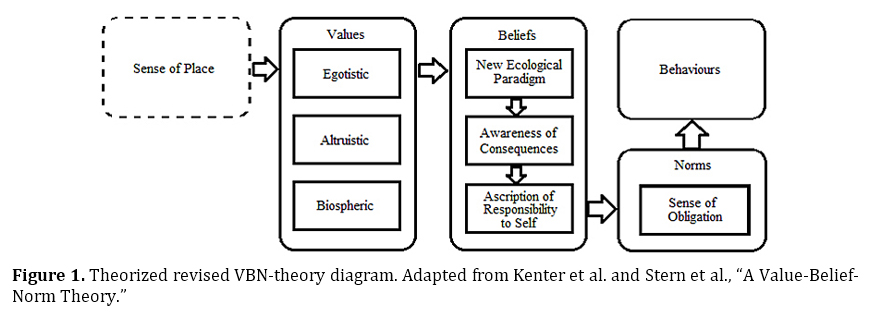

Examples of Place-Based Education in the Literature

16 A literature review turned up no explicit examples of university-level place-conscious pedagogy courses, which we define as courses with the primary focus of helping students to develop a sense of place. This is consistent with Armstrong’s observation that despite studies emphasizing the value of positive learning strategies, few universities are experimenting with alternative learning methods. There are some studies of place-conscious learning at the primary and secondary level, and additional studies in which it is incorporated into specific subjects. Greenwood identifies a number of strategies to reconnect students with place, including experiential and context-based learning, outdoor education, service learning, and Native American education (Gruenewald, “Foundations of Place”). This study addresses an important gap in our understanding by evaluating the benefits of place-conscious pedagogy at the undergraduate level, using student reflections on the Place Matters course.

Principles of Learning

17 This section reviews the research on how students learn and what makes for a strong learning environment. Understanding how we learn while we are learning improves the overall learning process (Bransford, Brown, and Cocking). Place-conscious pedagogy seeks to maximize the potential for intellectual growth by shaping the learning environment to cater to the needs of students. Therefore, to evaluate place-conscious pedagogy, it is important to compare the experiences of students in the Place Matters course to key principles of learning drawn from the literature. In this study, we assess the extent to which Place Matters adheres to recognized good learning principles. If a course focused on place-based education is able to effectively adhere to the key principles of learning, it can be argued that the course is successfully changing students’ knowledge, beliefs, and behaviours. We will then be able to explore additional learning benefits of this method of teaching.

Seven Key Principles of Learning

18 In their book How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching, Ambrose et al. identify the key factors for effective teaching. These principles are rooted in the understanding that learning is a process that changes a person’s knowledge, beliefs, behaviours, and attitudes. The seven key principles of learning are briefly summarized here.

19 The first principle is that “students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder learning” (4). Students’ past experiences act as a filter on what and how they learn, connecting what they are learning to what they already know. The second principle is that students’ ability to organize knowledge can influence their capacity to learn and apply knowledge. Students are better equipped to acquire knowledge when they can make connections during the learning process. The third principle is that “students’ motivation determines, directs, and sustains what they do to learn” (5). If students see value in what they are learning, they are more motivated to continue to learn. In order to develop such values, the authors argue that material should be connected to students’ interests, should employ real-world tasks, show relevance to current academic life, and promote the long-term benefits of the subject (84). The fourth principle states that “to develop mastery, students must acquire competent skills, practice integrating them, and know when to apply what they have learned” (5). This supports Bransford, Brown, and Cocking’s argument that learning is a staged process and that knowledge accumulation needs to be incorporated into practice to achieve mastery.

20 The fifth key principle emphasizes the importance of goal-directed learning refined through regular student feedback (Ambrose et al. 5). This happens when opportunities for students to practice and set goals are regularly integrated into the curriculum (127). The sixth principle is that “students’ current level of development interacts with the social, emotional, and intellectual climate of the course” (6). Simply put, students will learn better in an open, positive, environment set by the tone of the instruction and the learning setting. The seventh and final principle states “to become self-directed learners, students must learn to monitor and adjust their approaches to learning” (6). The authors argue that students need a certain level of independence in planning and self-evaluation.

21 An important characteristic of courses that recognize these principles is that they provide students with the opportunity to reflect on their learning (89). They also balance between flexibility and control of the learning setting (90). These concepts will be useful in evaluating our course’s teaching method, and can act as a baseline for determining whether students are benefiting from an effective learning environment.

Sense of Belonging

22 The above principles of learning do not entirely address students’ sense of belonging, which is often an important part of a sense of place. In College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for All Students, Terrell Strayhorn argues that a student’s feeling of connectedness and feeling of importance is vital to the undergraduate education experience. This “sense of belonging” affects a student’s academic performance and his or her incentive to stay in school (2). Strayhorn’s definition of sense of belonging relates a person’s sense of belonging to his or her sense of identification relative to the wider university community. This acts as “a precursor to community,” meaning that it helps to foster healthy learning environments (8). This definition, and the benefits he associates with a sense of belonging, are similar to the definition and arguments for developing a sense of place.

23 Sense of belonging and sense of place are interconnected concepts. When students feel as though they belong, they are happier, are more likely to stay in school, and perform better. Strayhorn further argues that students who feel like they belong achieve higher grades. Thus, if a course has a positive effect on students’ sense of place, it would also foster a stronger learning environment.

Place-Conscious Pedagogy and Value-Belief-Norm Theory

Place-Conscious Pedagogy

24 Place Matters was designed to help Mount Allison students develop their sense of place within Sackville. Place-conscious pedagogy is a reaction to educational reform policies and habits that disregard places and ignore the relationship between education and economic development (Gruenewald “The Best of Both Worlds”).

25 There is an ecological dimension of place, in addition to its social and economic dimensions. When people consciously live, consume, and dispose of waste at the local level, it provides them with a greater understanding of their own environmental impact, which can lead to a greater care for shared spaces (Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”). When a person has a stronger connection to a place, he or she is more likely to feel a greater responsibility to protect it.

26 Improving students’ perceptions of place may lead to a wide range of benefits. A sense of place is needed to understand our globalizing world, as understanding international communities is easier when a person has a strong understanding of their own place (Greenwood; Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”) . According to de Carteret, there is a connection between place, preservation of the environment, and the preservation of cultural diversity that, once recognized, has the potential to benefit all of these areas. Woodhouse and Knapp argue that this connection exists because place-conscious pedagogy prepares students to live in a way that respects the integrity of the culture and ecology of their places. As de Carteret has shown, both students and non-students learn, accidentally or intentionally, through participation and engagement in the community, a type of learning not teachable in the formal classroom setting. Place-based education can also improve students’ ability to be self-directed in the learning process and the application of knowledge (Gruenewald “The Best of Both Worlds”).

Evaluating Place-Based Initiatives

27 A few methods for evaluating place-based initiatives have emerged from the literature. The Rural School and Community Trust Place-Based Education Portfolio Rubric, written by Perrone, Cervone, McCoy, and Thompson, offers one such method. This rubric assesses student learning, community learning, and the expansion of knowledge of place through a detailed rubric that ranks projects in multiple categories from the beginner to advanced level. This self-evaluation method determines whether or not a project is a strong example of place-based education, but does not allow for deep exploration into some of the benefits of program participation. The other criticism of the rubric is that it is attempting to quantify place, a naturally qualitative principle. Therefore, as explained in the remainder of this section and in the methodology section, this study uses qualitative methods to evaluate the place-conscious aspects of the course.

Value-Belief-Norm Theory

28 While there are intrinsic benefits to place-conscious pedagogy, in order to discuss the wider impact of the Place Matters course, it is important to be able to connect course participation with any changing social values related to place that affect students’ actions within the wider community. Greenwood argues that when the curriculum allows for student exploration of place, students respond with increased empathy to their surroundings (Gruenewald “The Best of Both Worlds”). The value-belief-norm (VBN) theory proposed by Stern, Dietz, Abel, Guagnano, and Kalof suggests that changes in students’ understanding of place, and hence their values, should have an effect on society as a whole. The theory argues that changes to people’s values can affect the three groups of non-activists vital to any social movement: low-commitment individuals who make donations and write letters (low impact); those who support and accept public policies (medium impact); and those who make changes in behaviour in the private sphere (high impact). These potential benefits are a strong argument for incorporating an awareness of place into the curriculum. Therefore, an important aim of this study is to determine if there is a positive relationship between the Place Matters course and these changes.

29 The VBN theory has been used to explain support for the environmental movement, based on the argument that the environmental movement is broadly embedded in society (Stern, Dietz et al. “A Value-Belief-Norm Theory”). It seeks to explain non-activist environmentalism, that is, a tendency to exhibit moderate pro-environmental behaviour. Values, beliefs, and norms are described as “feelings of personal obligation that are linked to one’s self-expectation” (91). The overarching argument of Stern et al. is that norms, or personal tendencies to act in a certain way, are rooted in a person’s individual values. Therefore, the experiences that have shaped a person’s values throughout their life will affect how they approach specific issues and new challenges. For example, the environmental movement is built on the values of civil rights, human rights, and social justice.

30 The VBN theory links norm-activation theory, the theory of personal values, and the new ecological paradigm. The new ecological paradigm (NEP) is related to the worldview that the Earth faces an increasing threat from human-induced climate change (Dunlap et al. “New Trends”). The norm-activation theory, as presented by Stern et al. (“A Value-Belief-Norm Theory”; Stern “New Environmental Theories”), states that environmental action is contingent on moral norms that are activated in people who see a threat to humans and other species (i.e., have an awareness of consequence (AC)), and who believe their individual actions can have a positive impact on this threat (i.e., have an ascription of responsibility to self (AR)). The personal value theory suggests that there are three values relevant to environmentalism: self-interest, altruism toward others, and empathy to other species. Phipps et al. argue that altruistic and biospheric values make an individual more likely to accept the NEP and take economic and political action to protect the environment. Thus according to the value-belief-norm theory, an alteration in a person’s values will lead to a change in their agreement with the NEP. Stern et al. argue (“A Value-Belief-Norm Theory”) that the subsequent modifications to their AC beliefs will lead to increased AR, and will ultimately result in a change in an individual’s personal norms for pro-environmental action. In this model, each link in the chain directly affects the next.

31 Stern et al. (“A Value-Belief-Norm Theory”) test the theory against three other theories and also compare the VBN’s predictive value with six other models; the regression analysis is strongly consistent with the VBN theory, making it the strongest explanation for non-activist pro-environmental behaviour. Jackson’s 2005 study further supports the theory, finding a positive correlation between the acceptance of the NEP and biospheric and altruistic personal values. His study additionally finds that acceptance of the NEP eventually leads to the development of personal norms related to engagement in environmental behaviours.

32 For this study, we hypothesize that participation in Place Matters may have an influence on the students’ values; in particular, they may develop a greater appreciation and sense of ownership in their community. If it is possible to determine a positive relationship between students taking the Place Matters course and a change in their environmental attitudes over the week, this will support the argument proposed by the VBN that improving one’s sense of place can lead to a long-term positive impact on the community. Figure 1 illustrates these hypothesized relationships. It connects the theory that development of sense of place can impact a person’s values with the VBN.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

33 It is important to be cautious when discussing the VBN theory because our behaviours and norms are based on well-grounded values, and these values tend to be more resistant to change in the face of new information (Stern et al. “Values, Beliefs, and Proenvironmental Action”). Place Matters’ ability to change student values is one focus of this study.

Methodology

Mount Allison as a Case Study

34 The size, length, and style of the course made the case study an appropriate research method for this project. Within case studies, the researcher is the main source for the collection and analysis of the data. This case study is comprised of interviews with participants and notes made during participant observations.

35 One drawback of the case study method is that it is often argued that they cannot be generalized to apply to other scenarios. However, Yin has shown that case studies, when observed on their own or in collaboration with other case studies, can be used to help generalize to theory. This generalization to theory is an important component of this article; it links the students’ participation in Place Matters to the theory described in the literature. Furthermore, Merriam argues that a case study is appropriate if the researcher has determined that the associated strengths outweigh the limitations.

Semi-Structured Interviews

36 The interviews were semi-structured, consisting of three sections designed to direct responses into categories. The first section encouraged students to discuss an experience when they felt a strong sense of place with Sackville and what features they associated with these feelings. The aim was to understand how students define place, how they experience it when they are in Sackville, and what features are commonly associated with place. The second section focused on the students’ experience in the Place Matters course. The questions were designed to have students recall memorable moments and to have them reflect on how, if at all, their own sense of place might have changed during the week. This section also collected information on whether the students felt there was any merit in this type of learning and how relevant it was to their own degree. The final portion of the interviews asked students about their thoughts on the way the course was delivered. This portion was intended to determine whether the students’ thought the week-long intensive course design was appropriate for the subject matter. All of the students were informed that their responses would remain confidential in the reporting process. Each student has therefore been assigned a pseudonym for use in the Results and Discussion sections.2

Critical Incident Interviewing of Students

37 During the interviews, the research study drew upon Flanagan’s critical incident technique. Critical incident technique (CIT) is used to measure direct observations of human behaviour by having participants recount personal experiences. Given the connections and emotions associated with developing a sense of place, CIT was selected because it allowed students to describe their own instances of feeling connected to place. To apply the CIT, the interviewee is simply asked to elaborate on a significant and memorable experience (Hughes et al.). The method normally involves an initial conversation designed to generate critical incidents, followed by an elaboration on one moment selected either by the researcher or interviewee (Center for Reflective Community Practice at MIT). The story told by the interviewee provides the researcher with raw data that needs to be categorized and interpreted (Flanagan).

38 In this study, the interviewees were asked to describe a moment where they felt a strong sense of place in Sackville; these critical incidents were categorized and organized based on commonalities such as the description of the location, emotions, and physical traits of the place. An analysis of the critical incidents identified similarities, differences, and patterns to explore the first two research questions of this study.

39 The research was conducted in a course delivered at Mount Allison University, a small liberal arts university in Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada. Research participants were solicited from students who participated in the course, with nine of the ten students agreeing to participate in the study.

Results

40 This section presents data from interview transcriptions and notes taken during participant observation. The interview summaries were compared to identify categories and themes, which were supplemented by observations recorded during the week.

Characteristics of Place Using the Critical Incident Technique

41 Having students describe instances when they felt a deep connection with place in Sackville allowed for the identification of key factors that students associate with place. Landscape, people, and emotion were all important aspects of place for Place Matters participants.

42 The landscape played a key role in five students’ critical incidents. Two students discussed looking over the marshlands and seeing the radio towers and wind turbines. Another student talked about walking alone through Waterfowl Park, while another’s favourite place was standing in the middle of the soccer field. One of the international participants described feeling a sense of place when lying in the grass near the highway at night and looking up at the stars. A common thread in these incidents is that students experienced them while they were alone within the landscape.

43 Other students found their connection to place rooted in the people around them. One female student said, “The places I’ve gone that I’ve had the strongest sense of place are when I’m with people that are from the community and that have really deep roots here and you feel as though you are on the same level as them.” Another student talked about attending Sappyfest, an annual music festival, and how seeing other people interact with the town made him realize the quality of the community and how tight-knit the town was. For these students, a sense of place was often about being part of the community outside of their role as a student.

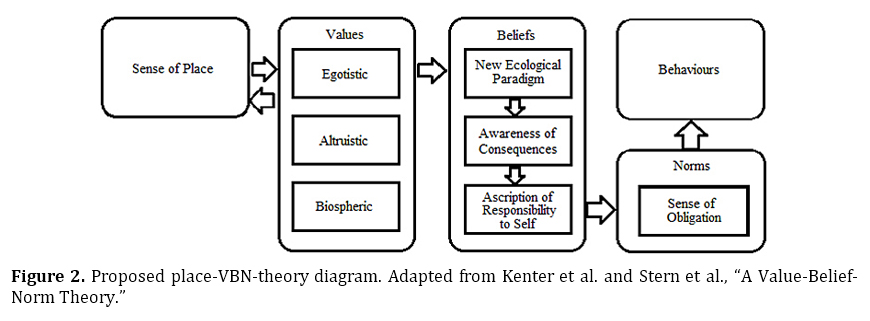

44 Only one student referenced the university in her example of connection to place. She talked about driving into the city after being away for the summer and recalling memories she made in her first year. She said that the reason her sense of place incorporated only the university was that she had never experienced a sense of place outside of the campus.

45 All of the students referred to their emotions when discussing their critical incidents. Two students suggested that their feeling of place came from seeing the landscape and being reminded of home. Two other students attributed feelings of calmness to their sense of place.

Other Characteristics of Place According to Students

46 Several additional characteristics of place were mentioned in other sections of the interviews and during the course. Place was described by one student as something that you experience, while another described it as a collection of memories you associated with a given space. Another student described it as “space with meaning.” To some students place was associated with the comfort of home, whether it is a landscape, a community, or an activity. In his interview, environmental studies student David suggested that while it is easier to develop a sense of place in smaller towns, it is not impossible to do the same in big cities.

47 During the course, the notes from participant observation identified additional characteristics of place. The students believed that parents play a big role in influencing sense of place growing up, which is why it is so hard to connect to a new place. They also suggested population size as a factor, and said that people from places with larger populations have a more difficult time connecting to place in small communities, and vice versa. An international student mentioned food and language as characteristics of place. She referenced a Chinese grocer who drives into town once a week to sell to students, and how aspects of a previous sense of place can help to develop a new sense of place. Lastly, the geography, such as being near the water, can influence place, as can understanding a place’s history.

Changing Perceptions of Place

48 One thing that was agreed upon in every interview was that students felt that the course really allowed them to get to know Sackville. Students learned about the Canadian Wildlife Service, the history of the town, the buildings, the sustainability efforts, the social organizations, and much more, all of which were brought up in the interviews.

49 In the interviews, students mentioned ways in which their sense of place had been altered during the course of the week. David said he became aware of people’s ability to shape place in Sackville, stating, “I realized that there are people that are influencing the place, rather than the place just organically doing things without any sort of human influence from the people.” Taking the course made another student realize how easy it was to interact with the community. Li defined place as “a physical location” before the course and during his interview said “place for me now is physical and also mental.”

50 There was an apparent increase in the emotional component of understanding place among students. One student mentioned that after visiting the seniors’ college, a community-based initiative that offers a variety of courses to senior citizens in Sackville, he realized that compassion was part of having a sense of place. Another student described passion as a characteristic of a sense of place; she realized this after reflecting on the energy and interest that each visitor expressed to the class, particularly the in-depth presentation on the history of Sackville.

Benefits of Connecting to Place

51 The responses collected during the nine interviews demonstrate that students unanimously agreed that they benefited from developing a sense of place. Jackie said that place-based learning does not distract from learning the basics, contrary to the beliefs of some people she had discussed the course with. She argued that it made learning the basics easier, by making them more relevant. An international student who took the course pointed out that when you are aware of place, you see problems and you can use your education to address them. For her, the week taught her strategies for applying her knowledge in the real world.

52 Student interview responses described a new way of interpreting knowledge that comes from developing one’s sense of place. One student said, “I think for genuine education, it’s important to understand the big picture,” referencing place as a key part of that big picture. Fourth-year student David said, “I think with this course it was much more about changing your way of thinking than wanting to give you a surplus of knowledge and then being tested on it….I think it created a lens that you can look at your other courses through.”

53 The following are quotations taken from interview conversations about the benefits of place-conscious pedagogy.

- I think it would give you a much greater understanding of what the actual issues are if you see them first-hand instead of just reading about them. (Jackie)

- People in the community have a huge impact on how intelligent you become, how discerning you become, how compassionate you are in terms of issues and things like that, than just professors and whatever it may be. (Jackie)

- You learn it, you don’t just remember. You really learn it. (Jun)

- If you become accustomed to the people in a place, then you’re less likely to commit any wrongdoings against them. (Crystal)

- If you’re more comfortable in a place, you’re going to end up being more successful and happy generally....[People] feed into your sense of place which ultimately makes you happier and do better at what you are trying to do here in the first place. (David)

Town and Gown Relationship

54 A common theme from the week and in the interviews was student perceptions of the relationship between the university and the town. Many had been aware of the relationship, but most had not realized the amount of conflict that occurred between the two groups on a regular basis. Students were exposed to stories of both residents and students participating in disrespectful behaviour. This included vandalism and excessive noise caused by students, and rental discrimination and false accusations made by residents. Having taken the course, a female commerce student said, “Whether or not I agree with the two sides of things, I see both sides.” Her comment shows that she has developed a fuller comprehension of how she and other students contribute to the relationship and how that relationship affects place.

55 There was concern from one student who did not understand how so many students could pass through the university and make no effort to improve this relationship; but then she admitted she would probably never have seen the problem had she not enrolled in the course. In reflecting on the relationship, Jackie said, “Seeing the relationship makes you say ‘Wow, I really do have a responsibility to try and make that better.’”

Developing a Sense of Responsibility

56 It became apparent in the interviews, through direct and indirect comments, that during the week many students had developed a sense of responsibility to place. They came to believe that they had a responsibility to improve place or preserve the sense of place for everyone. Indirectly, this was demonstrated through a student expressing a desire to volunteer at the seniors’ college and another student raking her lawn over the weekend because she wanted the neighbours to see she cared about the property and she thought it might make her street look nicer.

57 More direct examples of a developed sense of responsibility came from comments made in the interviews. The only chemistry student in the course said that she felt that the knowledge she gained during the week came with an obligation to do something to better the community or improve the relationship between the university and the students. This was elaborated on by two other students in separate interviews who argued that when you know a place, the sense of responsibility comes from feeling accountable for anything that may happen to the place now that you have connection to it. Seven of the nine students interviewed mentioned that their feelings of some obligation or desire to further engage with various aspects of the community increased after they had taken the course.

Making Connections

58 In the interviews, as students answered questions or provided examples, they would frequently draw connections to their own education and experiences. One student said she found herself regularly comparing life for citizens of Sackville to those in China; in particular she referencing the Sackville Seniors’ College and said there are not as many learning opportunities for seniors where she comes from. A commerce student drew connections between the week and her own degree, and discussed how spending patterns are shaped by the way you feel about place. She argued that how businesses interact with their communities can influence their success. Another student explained how the presentation on the history of the town had him reflecting on the town planning and the economic repercussions of businesses moving from the town centre toward the highway.

59 Other students mentioned in their interviews connecting the subject matter to global climate change, poverty levels in the region, and problems in their hometowns. These examples are evidence that students were connecting what they were learning to what they already know.

Changing Values

60 The interviews showed that students’ critical incidents were related to their personal values. The two international students mentioned that their preconceived understanding of how people learned was challenged when they began knowing and learning through their experiences in Place Matters. Students mentioned compassion for place following visits to the Canada Wildlife Service and Sackville Seniors’ College. One student talked of the course creating a lens through which he can look at his other courses, which suggests he has altered how he makes decisions about processing and using information, a characteristic of values.

Questions on Teaching and Learning

61 Discussions during the course and in the interviews regularly drifted toward the topic of teaching and how students learn. The students argued that people learn in many different ways. There was also an acknowledgement that lectures and testing is needed for some subjects, but as one student said, “You need a balance and the balance isn’t there.” The students mentioned in a class discussion that place-based education can help instructors remain relevant and engaged in both their classroom and research by applying subject matter to real-world and local issues. Despite these strong feelings about the way their learning experience could occur, the students did not feel that they had any significant influence on the way academic programs are designed or delivered.

62 The style in which the subject matter was presented garnered mostly positive responses as well. A student mentioned that having guests give up their own time to speak with the class meant that he felt a greater obligation to listen and engage in discussions. Most students also agreed in their interview that the size of the class had a positive effect on their experience, because it allowed for constructive and interesting discussions related to the subject matter. Two students credited the atmosphere of the class for improving their confidence in speaking in front of others and participating in discussions. The length of the class was also a favourable characteristic for most students who liked being able to immerse themselves in one course, saying that it allowed for greater knowledge retention in addition to providing more time to reflect on what you learn as you are learning it.

Discussion

1. How do students in the Place Matters course understand or experience place?

63 Students’ definitions of place included forming memories somewhere, experiencing things firsthand, space with meaning, and the emotions associated with one’s surroundings. What was apparent is that the students had varying definitions that were based on their personal histories and educational backgrounds. These factors also affected how students experienced place, as the Place Matters student from Sackville had a much different experience over the week than the two international students.

64 Students’ descriptions of how they experience place and the ways they interacted with place during the week reflected their different understandings of the terms. The students sought to explore new areas in the town in an effort to create new memories and talked about finding things that reminded them of home in order to better relate to place. Students said they experienced place by engaging with the people and the landscape first-hand. When students were given the opportunity to go out for an afternoon and experience place for themselves, most of them chose to explore areas of the town they had never ventured into before. In these new places, they met new people and asked them questions in order to gain more understanding of the place they were in. It seems as though to experience place, the students believed you have to interact with the landscape and people in new ways to develop new memories and to learn more about where they are.

2. What factors do students think help connect them with place?

65 The students suggested that parents, people, the landscape, the size of the population, food, and language all play a role in developing one’s sense of place, no matter where that place is.

66 The discussion of parental influence in developing sense of place was interesting because it showed that for most students, their experience in Sackville was the first time they had developed a sense of place independently. It became apparent that not all of the students felt comfortable enough to independently engage with the people and spaces that could enrich their sense of place. This observation supports the arguments that place-based learning should be incorporated into undergraduate education to help those students who need guidance to develop a sense of place on their own.3

67 It also seems that students felt that being a part of the community influences their sense of place. Their responses supported the research discussed above on the importance of a sense of belonging for undergraduate students. In two students’ critical incidents they associated place with feeling part of the community, and wanting this feeling acted as an incentive for another student to join the course. These comments show the students’ desire to be a part of the community. Thus, by helping students to know their place better, it is likely that this course gave them a greater sense of belonging.

68 Other factors identified in the critical incidents suggest that some students connect better to place when they are alone, while others require a level of human interaction. There also seemed to be a sense of pride associated with a strong sense of place; this was expressed in one student’s story about attending the annual music festival and feeling excited that strangers from across the country would be interacting and experiencing Sackville. Two others talked about showing friends and family around the town and being able to point out landmarks and special places in Sackville. There is also a feeling of comfort and calmness that comes from connecting to place that was evident in the critical incidents. Overall, students combined a wide variety of physical, historical, emotional, and social factors when connecting themselves to place.

3. Can a week-long intensive course effectively change undergraduate students’ perception of place?

69 The objective of the course was not to teach one specific idea of place, but to provide an opportunity for students to develop and expand their own definition of the concept.

70 The one-week intensive period appears to have abided by the key principles of learning described in the literature review. The course design adhered to Reid and Nikel’s criteria: courses should give students opportunities to participate (class discussions); should give students opportunities to take control of their learning experience (interviews, place exploration, and independent projects); and have an innovative format (the week-long intensive structure of the course). Place Matters provided students with an alternative learning environment to explore their connection with place; its characteristics are consistent with the literature on effective learning principles.

71 In addition to demonstrating that the style in which the subject matter was delivered is consistent with the key principles of learning, the data appear to show that the week had an influence on students’ perception of place. The students agreed that they learned a lot about the town and its history. When people learn more about the places they inhabit, they tend to feel greater responsibility for its public spaces (Gruenewald “Foundations of Place”). This was evident in the collective obligation to do something with the knowledge they gained. This responsibility for these students was a recent feeling, and indicates that their senses of place were improved during the course. The results also showed explicit examples of students discussing ways in which they saw their own sense of place develop. This analysis of the data shows us that students were able to deepen their sense of place by completing Place Matters.

72 It appears that the length of the course was effective in helping students enrich their sense of place. The course length still allowed for the key principles of learning and there is sufficient evidence from the interviews to argue that students were able to develop their sense of place during the week by engaging with different aspects of the community and being given the opportunity to discuss their experiences.

4. How do students’ definition and understanding of place differ from the literature?

I find place is defined as memories and when you refer back to the places you may not necessarily realize you’re in the place at the moment. (Jackie)

It’s somewhere that you feel comfortable in, that you know very well. (David)

Place is where you feel at home. (Hannah)

73 The students appear to have picked up on the academic definition of place during the week’s discussions and readings. The students’ definition of place does not go much deeper than the emotions associated with space, which is most likely a result of this being an introduction to the concept of place for some, and an introduction to Sackville as place for many. A longer course or an extended opportunity to work on graded content for the course may have helped to develop this definition further. The students were only being introduced to the ways that the environment, culture, and politics work together to shape place. Their development and understanding of place could be further developed over time.

74 The students each had different definitions of place and varying senses of place that were based on their previous experiences in Sackville and other places. This coincides with previous research suggesting that no space invokes the same sense of place for two people, and that it is a purely subjective concept crafted by each individual based on their own life experiences.

75 Some of their conversations suggest their understanding has become much deeper during the week. During the week and in the interviews, students were engaging with the community, making connections to their own histories and education, participating in discussions and actively contributing to the class, and developing a sense of obligation to do something to better where they were, all of which was done while enriching their sense of place. These behaviours and outcomes are the focus of the place-conscious pedagogy research and these results suggest that the course was successful in not only developing each student’s sense of place, but also in supporting claims made by researchers regarding the merit of place-based education.

76 The results highlight the relationships between sense of place, values, awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility to self, and norms and behaviours in a way that supports the VBN theory. The VBN theory explains the connections between values and beliefs and agreement with the NEP. Figure 2 shows a diagram of the proposed place-VBN theory that is drawn from this study’s findings. Figure 2 is adapted from Figure 1 to illustrate the proposed relationship between sense of place and values.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Conclusion

77 This analysis of place-conscious pedagogy and how it influences the environmental attitudes of undergraduate students enrolled in Place Matters at Mount Allison University has provided evidence for the value of place development in undergraduate students. Place Matters applies the key principles of learning, and has been successful in helping students enrich their sense of place in Sackville. The students developed a wide array of definitions of place that were consistent with previous research, and have learned and discovered ways of experiencing place. The students themselves identified the benefits of place-based education, suggesting it will help them enrich future learning by showing them how to incorporate knowledge into the bigger picture, that it can contribute to an improved relationship between the town and gown, and that it helped with skills such as public speaking and critical thinking.

78 The results of this study support the continued promotion of place-conscious pedagogy. It has provided both concrete and theoretical examples of the benefits of improving sense of place during the undergraduate learning process. This new approach to learning may help students become more cognizant, potentially affecting their environmental and social practices. Based on the results, there is strong justification for pursuing place-based learning strategies at the undergraduate level, either directly through courses like Place Matters that aim to specifically improve students’ sense of place, or by incorporating place-based education into other courses in the syllabus.